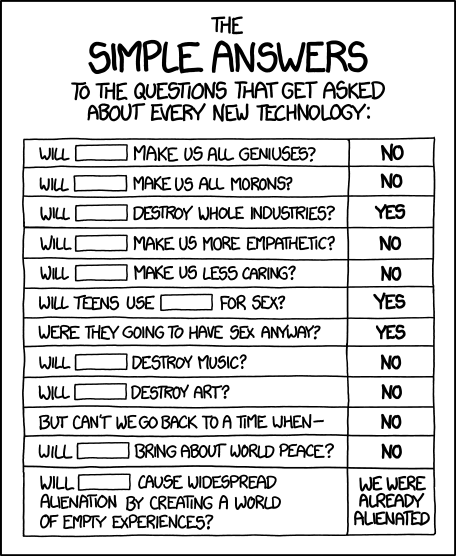

As many arts marketers, social media gurus, and nonprofit professionals attest, the question for nonprofit arts organizations is no longer whether or not to use social media but rather how to use it most effectively. This shift is reflected by AMT Lab readers’ responses to our 2014 AMT Lab Reader Poll, where a whopping 76% of respondents indicated they would like to see additional research on social media analytics while only 31% indicated interest in research on social media platforms themselves.

So You've Got Some Data...Now What?

We seem to hear it everywhere we go, at conferences, from consultants, and in myriad publications: to run arts organizations more effectively, arts managers need to adopt data-driven business models. An increasing number of data collection tools are emerging on the market with capabilities and price points that have the potential to meet the needs of arts nonprofits, from CRM systems like Artful.ly to social media management software like Buffer. But once you’ve collected some data, how do you use it? Be it information about your patrons, regional demographics, or marketing trends, how can arts organizations take advantage of incoming data?

Performing Arts in the Wearable Age

Wearable computing devices--including smartwatches, fitness and health tracking devices, and smartglasses--are projected to quadruple between now and 2018. What does their increased use mean for the performing arts? In their follow-up paper to "Through The Looking Glass: How Google Glass Will Change the Performing Arts," guest correspondents Thomas Rhodes and Samuel Allen explain wearable technology, provide an overview of current experiments with these devices among performing arts professionals, and discuss potential implications and challenges for the field.

And the Winner Is! Results of the 2014 AMT Lab Reader Poll

Brave New World: Symphony Orchestras & Online Experiences

Just what is an online audience? How does it differ from an offline audience? How does participating in the arts through electronic media and online channels relate to the attendance of arts events? Moreover, exactly what (and how) are symphony orchestras using these digital technologies to engage with individuals around the world?

AMTLab Reader Poll: Sound Familiar...or All Wrong?

Three questions, three wishes...and a three-way tie. As AMTLab prepares to close its 2014 Reader Poll at the end of the week, we're in a dead heat for the topics of most interest to our readers.

The Magic of Three: AMTLab Reader Poll

Navigating the Cloud: A Practical Guide for Arts Organizations

Just what is the cloud and what benefits might it hold for arts organizations? What makes a transition to cloud services worthwhile? And what cautions should be heeded when considering such a transition? This report from AMTLab contributor Stewart Urist introduces the basic categories of cloud services and discusses the potential benefits and risks they hold for arts organizations of various sizes. It's available now in AMTLab Publications.

Data-Driven Decisions for Arts Marketers

AMTLab contributor Christine Sajewski discusses strategic uses of internal arts marketing data, as illustrated through a hypothetical performing arts organization, the Ugly Duckling Ballet. Read the full report here.

News Summary 11.2013

Database Decisions for the Nano-Nonprofit: Part 1

Arts organizations of all sizes grapple with the question of how best to house information on the array of individuals with whom they interact. From ticket buyers to donors, members to volunteers, every arts organization builds a variety of relationships with a variety of constituents. Complicating matters, of course, is that many times these groups overlap. For the organization that wants to understand all the dimensions of its patron relationships, obtaining complete and nuanced profiles is often a challenge, time-consuming at best and impossible at worst. Recent years have seen a burgeoning of Constituent Relationship Management systems (CRMs), about which a wealth of literature is available.

The Meaning of the Moment

On November 16, The New York Times published an essay by its music critic Anthony Tommasini reflecting on several of his favorite moments in classical and operatic repertoire. “I’m not talking about big climactic blasts or soaring melodies,” he writes, “but about some fleeting passage, an unexpected twist in a melodic line, a series of pungent chords, a short theme that reappears briefly in a new musical guise. Often these moments are subtle and quiet, almost stealthy.” He describes such moments as magical, fleeting, transcendent. Be it listening to a piece of music, sitting in a theater, watching a dance, or gazing at a piece of art, lovers of every art form surely know the sensation of which he writes—those split seconds where time seems to stand still and we are immersed in a realm beyond ourselves. As part of the project, Tommasini asked readers to share their own experiences of musical treasure. Overwhelmed by the response (to date, the query has received 875 replies and counting), what followed is a nine-part video and blog series in which Tommasini takes off the hat of critic and dons the role of teacher. Each video dissects one particular musical moment. Seated at his piano, Tommasini plays through the passage in question, simultaneously discussing its musical narrative and highlighting the particular nuances that cause it to grab the listener just so.

[embed width="560" height="315"]http://www.youtube.com/watch?feature=player_detailpage&v=AkeOC36Bmpo[/embed]

Like any fine instructor, Tommasini presents the subject matter with enthusiasm and knowledge. But unlike a lecture from an expert, the relevance of the session is derived as much from the audience as the teacher. Essentially the project asks devotees of an art form to reflect on their devotion. The subject is important not because an expert declares it so, but because the listener does. Tommasini comments in a follow-up essay on December 9 of the passion, intelligence, and clarity with which readers replied. Of the end of Debussy's Clair de Lune, one writer comments on the change of a single note, resulting in a "subtle change of harmony, like the instant of recognizing first love on a moonlit night." These moments, though brief, are deeply felt and moreover, personal.

As an engagement tactic, it’s a strikingly simple concept. Ask your current audience what moves them. Nudge them to remind themselves of their passion for what you do. In the process, create a forum for lively conversations to occur and then listen to what is shared. Tommasini’s “Musical Moments” project, of course, is able to utilize the human, financial, and technological resources contained at The New York Times. But with such a fundamental question driving it, we wonder if any arts organizations have taken on similar endeavors. To current arts managers who follow our blog, how does your organization garner feedback from the audience about their motivations for the art form you present? To arts patrons, have you participated in anything along the lines of the “Musical Moments” project? Would you want to?

Image Credit: Jillian Tamaki, Copyright 2012 The New York Times Company.

Last Call! Tech Challenges in the Arts Management World

We'll be closing our audience poll this Monday, January 21. Now is the time for you and all of your arts-oriented colleagues to tell us what tech challenges you face on a regular basis. Then check back for results! [polldaddy poll=6814063]

Crowd-Sourced Curating at the Brooklyn Museum

As the arts world continues to discuss and reconsider what it means to participate in the arts, the Brooklyn Museum is testing a new construct of audience engagement with its current exhibit GO: A Community-Curated Open Studio Project. GO combines two existing tactics: inviting the public into studios of working artists to see where and how artwork is made, and crowdsourcing the selection of that artwork through an open voting process. Unlike ArtPrize, an art competition in Grand Rapids, MI, that awards cash prizes to artists as determined by public vote (juried awards were added in 2012) and cited by the Brooklyn Museum as inspiration for the current exhibit, GO asks participants to nominate artists—rather than specific pieces—whose work they would like to see exhibited at the museum. The catch is that to be eligible to vote, participants must first visit at least five artist studios, which in turn requires that the museum be able to track where people go. The answer is a multiphase project begun this past September and culminating in an exhibit of Brooklyn artists, on display through February 24.

To participate, the museum first asked individuals to register on the GO community project website. Then, over a two-day open studio event involving nearly 1,800 artists in 46 Brooklyn neighborhoods, participants “checked-in” at each studio visited by way of a unique number displayed onsite. By sending that number to the museum either by text message, a free custom iPhone app, or the web, participants documented where they traveled. Those who checked-in at five or more studios received an email with instructions on how to vote, having earned the opportunity to nominate up to three artists. The museum tallied the results, sent two of its curators to review the work of the top ten nominated artists, and selected five to exhibit.

But GO didn’t stop when the voting was done. By asking participants to check-in, the museum was able to analyze how many people went where, when, and what platform they used to check-in, all of which was then shared in a series of posts on both the GO blog and through the Statistics section of the GO website. (Among those findings: Despite multiple mobile-friendly options designed especially for the event, nearly half of the 6,100+ participants chose to simply write down studio numbers throughout the day and check-in via the project website once back home, surprising project coordinators.) The website also provided a forum for participants to discuss (in real time and afterward) what they did and did not like about the process, share stories from their studio visits, learn about nominated artists, receive updates on the creation of the exhibit, and provide reactions to the final exhibit itself.

The exhibit has been criticized by some for not aptly representing the rich artistic quality Brooklyn holds, and is generating commentary on the age-old curatorial question of who should decide what constitutes “good” art. While a worthwhile debate, it seems to belie the larger point of the project: to expose people to the creative process, and ideally, to facilitate a better understanding of it. On that score, GO appears to have succeeded mightily. As project coordinators tagged entries in the Shared Stories section of the website, one of the most frequent themes to emerge was that of discovery. It seems that by opening studio doors, inviting people to participate in the curatorial process, and sharing reactions online, GO fostered meaningful interactions among artists, voters, volunteers, and museum staff, and in the process, created an innovative approach to engage audiences in the arts.

Time of Transition

Does something seem different? Did we get a haircut? New pair of glasses? Start working out? Can’t quite put your finger on it?

Technology in the Arts recently embarked on the beginning of a yearlong journey to assess our role in the world of arts management and technology. Externally, you may notice changes to the look of our site as we continue to update our WordPress infrastructure. Internally, we are engaging in a strategic planning process to reposition and rebrand Technology in the Arts to better serve our audiences.

Part of that effort is to learn more about YOU. Throughout the coming months we will be polling our users to find out what challenges, triumphs, needs, and desires are lurking in the professional niches you inhabit. We invite you to participate, submit comments, and check back to see what we’re finding. What types of content would be most helpful to you? What questions do you have? What excites you? Where do you see arts management and technology intersecting? Where don’t you?

Transitions are afoot. Let’s begin!

[polldaddy poll=6814063]

Wanted: Arts Managers

Those who have been following Technology in the Arts (TiTA) for some time may be aware that in the past TiTA, in collaboration with the CMU Master of Arts Management program, hosted a website devoted to job opportunities in the arts management field: http://artsopportunities.org/. Since its inception, an abundance of free online arts job resources have emerged, and so, this month we say adieu to our companion site. In its place we present here a host of resources that come with high recommendations as you pursue or advance a career in arts management: National Listings

Americans for the Arts Job Bank

Association of Fundraising Professionals

Association of Performing Arts Presenters

National Alliance for Media Arts and Culture

National Guild for Community Arts Education

New York Foundation for the Arts

Regional Listings: East/MidAtlantic

Greater Philadelphia Cultural Alliance

Massachusetts Cultural Council

Emerging Leaders of New York Arts

Cultural Alliance of Greater Washington (D.C.)

Regional Listings: Midwest

Arts Wave (Cincinnati)

Cultural Alliance of Southeastern Michigan

Springboard for the Arts (Minneapolis/Saint Paul)

Regional Listings: South

Arts and Science Council of Charlotte-Mecklenburg (North Carolina)

Regional Listings: West

Northern California Grantmakers

Oregon Regional Arts & Culture Jobs

International Listings:

International Society for the Performing Arts

Redefining Participation: Notes from the Newspaper Industry

The Audit Bureau of Circulation (ABC) reported its latest figures on the American newspaper industry last week, noting that in the six-month period ending on 9/30/2012, circulation figures across the industry largely held steady. Sunday circulation increased by 0.6%, while daily circulation fell slightly, 0.2%. For an industry that has experienced a drastic nosedive over the last several years (some would point to the last two decades), these figures, especially when combined with those of the preceding six months, should come as a breath of fresh air. Leading the charge—if we’re feeling optimistic—is the sharp, ongoing rise of digital circulation, which now comprises 15.3% of the total mix (up from 9.8% the year before). That print editions continue to decline comes as no surprise, but what is striking is the degree to which digital gains are boosting overall circulation figures, in some instances resulting in tremendous increases for individual publications. A prime example is The New York Times. With a total average daily circulation of over 1.6 million, The New York Times expanded its reach by 40% since 9/30/2011—all of it digital. The nation’s leading newspaper, The Wall Street Journal, which began counting paid online subscribers in its circulation figures in 2003, experienced similar, if more modest, growth (9.4%), as did the Los Angeles Times (11.9%). So too in Newark (48.1%), Tampa Bay (30.4%), Honolulu (26.3%), Cleveland (20.5%)…the list goes on.

So what happened? Did Americans begin to read online newspapers en masse over the last two years? Likely not. Rather, ABC made significant changes in its reporting mechanisms to enable newspapers to more fully capture its “cross-media” audience instead of only its print circulation. The changes, which went into effect in late 2010, include metrics to audit and report digital newspaper editions that are accessed by readers on websites, tablets, and smartphones. It’s taken the industry time to figure out both how to deliver its products to audiences in desired digital formats and how to track these multiple modes of participation. But with 24 months of that data now collected, “year-over-year” comparisons can begin to be made that produce a decidedly more nuanced portrait of the industry.

Whether or not that picture is more or less bleak than before is open to debate, certainly. For the arts, it might be an encouraging note as the industry wrestles with how to measure and evaluate online modes of participation. The most recent NEA Survey of Public Participation in the Arts (2008) inquired broadly about the subject; one question assessed online access of any performing arts (theater, music, or dance) and another the same for visual arts. As the authors of Beyond Attendance: A Multi-Modal Understanding of Arts Participation (2011) advocate, additional research is needed to gain a more detailed understanding of online participation; measurement systems likewise have to adapt. If the newspaper industry’s experience is any guide, when they do, the arts will be far better positioned to assess, and ideally to serve, its audiences.

Image Credit: Steelworkers reading the newspaper, Aliquippa, Pennsylvania, July 1938; Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, FSA/OWI Collection, LC-USF33-002822-M2

On Demand, In Vain?

By Katherine Schouten Rick Archbold recently published a piece in the Literary Review of Canada exploring the impact of self-publishing on the future of literature. The swift rise of print-on-demand technology (POD), which enables users to produce small print runs of titles through cost efficient means, has inaugurated a rush of unfettered works. Visual and textual, personal and professional, fictional and factual, literary and mundane, POD capabilities have empowered all those who possess the inclination to publish self-created goods.

As Archbold acknowledges, such access brings with it thorny issues, of which much conversation has been, and is being, had. (A thoughtful example from Christina Patterson can be found in The Independent.) But his argument brings the quandary around to the other side: what work that ought to be considered “literature” is being passed over precisely because it’s not from mainstream publishers? What might otherwise be considered “legitimate,” if not for the stamp of “vanity publishing” currently affixed by the industry to volumes precisely because they are printed by the very authors who wrote them? More urgently to Archbold, what works of literary art may society lose because self-publication is deemed vain?

Underscoring these conversations is the dualistic role the medium of a book, physical or electronic, plays, both as a vehicle for art (i.e., literature) and as a dynamic tool of communication. It remains one of our most fundamental technologies; how we access it, and whom we allow or enable to produce it, is rapidly changing. But could it be that with this technological evolution we might reinvigorate the book’s latter role, as a tool? If so, arts organizations—indeed, nonprofits of all varieties—stand to benefit. Books self-published using POD carry the potential to serve as an effective means of promotion and commemoration, a revenue stream in the form of merchandise, a powerful platform to aid applications for grant and foundation funding, and an enticing incentive for tiered giving. Most providers (Blurb, Lulu, etc.) are now compatible with Adobe InDesign, further aiding the integration process by enabling graphic designers to work in a preferred medium (rather than being limited to proprietary templates). They also now have ebook options, to deliver self-published goods to potential readers in their preferred format.

The conversations and concerns surrounding the implications of POD and self-publishing on the broader industry will no doubt continue. But the possibilities they hold for the nonprofit sector are palpable, vanity or not.

For a primer on self-publishing, see Alan Finder’s recent article in the New York Times, “The Joys and Hazards of Self-Publishing on the Web.”