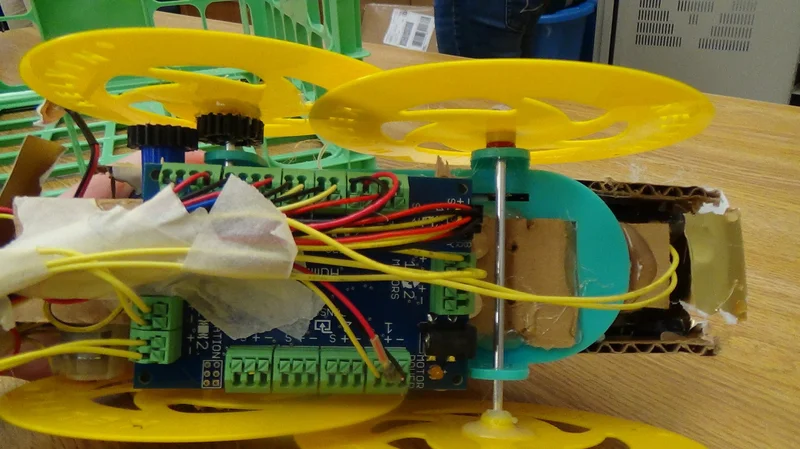

CREATE Lab creates multi-disciplinary learning experiences that allow communities to become technologically fluent. CREATE Lab’s novel combinations of visual arts and technologies provide a wealth of new potential tools to arts administrators and their organization. This article will introduce a few of the exciting projects that CREATE Lab is already testing in the Pittsburgh community, as well as access points for administrators and educators who are interested in implementing them.

News Summary 11.2013

A Virtual Orchestra

The Australian Chamber Orchestra (ACO) has teamed up with Sydney digital media company Mod Productions to produce a new interactive “virtual orchestra” that is breaking down audience barriers in the music world. The resulting audio-visual installation, “ACO Virtual,” has created the means to bring the Orchestra outside the concert hall and into spaces where the ACO may not perform.

Research Update: Creating Online Audiences for Orchestras

As a frequent concertgoer and prospective arts manager, I am intrigued by the question of how to create online audiences for symphony orchestras. What does it mean to create such an audience? And moreover, how does an online audience for an orchestra differ from the audience that comes to the concert hall? Or does it?

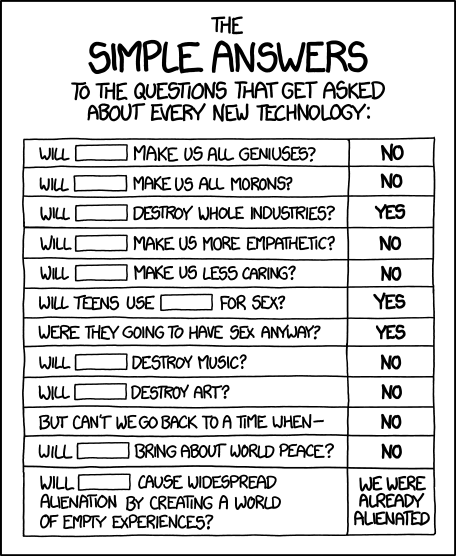

Keeping up with the times: Photos vs. Video

Just when we thought photos was the new rage in social media, video steps into the mix. I’m not talking about the typical YouTube video providing “how to’s”, news clips, music, or hilarious propaganda, I’m talking about the 30 to 15-second video applications now available through Instagram and Vine. I’m a huge photo sharer on Instagram, especially when I’m attending a cultural event; I love sending photos to my followers from my seat before a performance begins. Video, however, is becoming more and more prominent in our everyday social media lives. What does this mean for the arts?

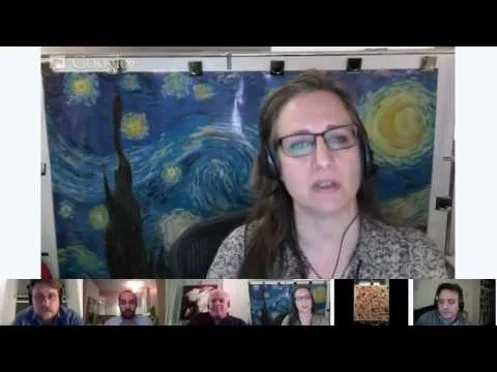

Bringing Art and Discussion to a Computer Near You: Introducing Google Art Talks on Google+

I am mildly obsessed with Google Cultural Institute. Why, you ask? It's two-fold. Firstly, Google has implemented its newest project to supplement the Google Art Project, Google Art Talks on Google+. As published on Google's Official Blog, "Each month, curators, museum directors, historians and educators from some of the world’s most renowned cultural institutions will reveal the hidden stories behind particular works, examine the curation process and provide insights into particular masterpieces or artists."

The Meaning of the Moment

On November 16, The New York Times published an essay by its music critic Anthony Tommasini reflecting on several of his favorite moments in classical and operatic repertoire. “I’m not talking about big climactic blasts or soaring melodies,” he writes, “but about some fleeting passage, an unexpected twist in a melodic line, a series of pungent chords, a short theme that reappears briefly in a new musical guise. Often these moments are subtle and quiet, almost stealthy.” He describes such moments as magical, fleeting, transcendent. Be it listening to a piece of music, sitting in a theater, watching a dance, or gazing at a piece of art, lovers of every art form surely know the sensation of which he writes—those split seconds where time seems to stand still and we are immersed in a realm beyond ourselves. As part of the project, Tommasini asked readers to share their own experiences of musical treasure. Overwhelmed by the response (to date, the query has received 875 replies and counting), what followed is a nine-part video and blog series in which Tommasini takes off the hat of critic and dons the role of teacher. Each video dissects one particular musical moment. Seated at his piano, Tommasini plays through the passage in question, simultaneously discussing its musical narrative and highlighting the particular nuances that cause it to grab the listener just so.

[embed width="560" height="315"]http://www.youtube.com/watch?feature=player_detailpage&v=AkeOC36Bmpo[/embed]

Like any fine instructor, Tommasini presents the subject matter with enthusiasm and knowledge. But unlike a lecture from an expert, the relevance of the session is derived as much from the audience as the teacher. Essentially the project asks devotees of an art form to reflect on their devotion. The subject is important not because an expert declares it so, but because the listener does. Tommasini comments in a follow-up essay on December 9 of the passion, intelligence, and clarity with which readers replied. Of the end of Debussy's Clair de Lune, one writer comments on the change of a single note, resulting in a "subtle change of harmony, like the instant of recognizing first love on a moonlit night." These moments, though brief, are deeply felt and moreover, personal.

As an engagement tactic, it’s a strikingly simple concept. Ask your current audience what moves them. Nudge them to remind themselves of their passion for what you do. In the process, create a forum for lively conversations to occur and then listen to what is shared. Tommasini’s “Musical Moments” project, of course, is able to utilize the human, financial, and technological resources contained at The New York Times. But with such a fundamental question driving it, we wonder if any arts organizations have taken on similar endeavors. To current arts managers who follow our blog, how does your organization garner feedback from the audience about their motivations for the art form you present? To arts patrons, have you participated in anything along the lines of the “Musical Moments” project? Would you want to?

Image Credit: Jillian Tamaki, Copyright 2012 The New York Times Company.

Jon Schwartz & The Kids Like Blues Band Program: How technology and music help children learn

“We’ve managed to incorporate tons of technology into our classroom. Over 90 % of my students have personal blogs. Through their individual blogs, the kids can keep their parents in the loop and show off their creative skills. I get instant email updates when they blog, and nothing is cooler than seeing one of my students post to their blog – over the weekend!- about guitars they wish they had! Oh how I can relate!”

------Jon Schwartz

Can you believe a six-year-old child is as proficient as you do in Photoshop and blogging? Yes! That is what’s happening at Garrison Elementary School located in Oceanside, California. Jon Schwartz, a blues guitarist and a second grade teacher, creatively uses the blues, blogs and Photoshop, as tools to educate kids. Jon’s teaching endeavors, creativity and energy seem highly relevant to arts engagement opportunities for organizations across the country.

The Kids Like Blues Band Program is about using blues music and lyrics as a springboard for teaching academic content standards in reading, writing, listening, speech, social studies, and the visual and performing arts. Based on a careful song selection, Jon chooses lyrics with the appropriate cadence, imagery, and kid-friendly content. Students then sing out the vocabulary given the rhythm, and in turn practice reading through repetitive and engaging activities. The kids themselves are encouraged to choreograph cool dance moves and motions to help them define and recall complicated vocabulary.

These activities provide children an encouraging and exciting environment that motivates them to learn new knowledge and unleash their creativities. Chuck Berry’s “Let it Rock” is one of the most popular tunes.

[embed width="560" height="315"]http://youtu.be/Nlg5n9GmpZE[/embed]

Students who are learning English, have speech difficulties or other learning disabilities, and just plain shy kids seem to develop more confidence as they learn the songs since the material presented to them is an engaging group practice, rather than them needing to talk by themselves in front of the whole class.

See how a Japanese girl benefits from the project:

[embed width="560" height="315"]http://youtu.be/8hCWFIPmD5Q[/embed]

Additionally, both high achieving and struggling students who have made tremendous gains tend to take leadership roles in their enthusiasm generating creative opportunities, such as designing dance moves, coaching others, blogging the artworks.

See how children create artworks through Photoshop and Blogging:

[embed width="560" height="315"]http://youtu.be/xt4AZ5XWQsM[/embed]

“Perhaps most importantly, my students’ self esteem is soaring and they are becoming passionate about lessons that would have otherwise been dull..”said Mr. Schwartz. These strong emotional responses to the arts are exactly what arts educators wants to generate in the children, what arts organizations want to generate in their audience, and what art wants to generate in the human soul. Mr. Schwartz’s model of creative participation and engagement can be translated to audience engagement models through online groups or onsite post-experience workshops. The opportunities abound for the arts to become as exciting to your audience as they are to these students.

Resource:

You will see all of the articles, TV features and 4 videos on their official website www.kidslikeblues.org

Crowd-Sourced Curating at the Brooklyn Museum

As the arts world continues to discuss and reconsider what it means to participate in the arts, the Brooklyn Museum is testing a new construct of audience engagement with its current exhibit GO: A Community-Curated Open Studio Project. GO combines two existing tactics: inviting the public into studios of working artists to see where and how artwork is made, and crowdsourcing the selection of that artwork through an open voting process. Unlike ArtPrize, an art competition in Grand Rapids, MI, that awards cash prizes to artists as determined by public vote (juried awards were added in 2012) and cited by the Brooklyn Museum as inspiration for the current exhibit, GO asks participants to nominate artists—rather than specific pieces—whose work they would like to see exhibited at the museum. The catch is that to be eligible to vote, participants must first visit at least five artist studios, which in turn requires that the museum be able to track where people go. The answer is a multiphase project begun this past September and culminating in an exhibit of Brooklyn artists, on display through February 24.

To participate, the museum first asked individuals to register on the GO community project website. Then, over a two-day open studio event involving nearly 1,800 artists in 46 Brooklyn neighborhoods, participants “checked-in” at each studio visited by way of a unique number displayed onsite. By sending that number to the museum either by text message, a free custom iPhone app, or the web, participants documented where they traveled. Those who checked-in at five or more studios received an email with instructions on how to vote, having earned the opportunity to nominate up to three artists. The museum tallied the results, sent two of its curators to review the work of the top ten nominated artists, and selected five to exhibit.

But GO didn’t stop when the voting was done. By asking participants to check-in, the museum was able to analyze how many people went where, when, and what platform they used to check-in, all of which was then shared in a series of posts on both the GO blog and through the Statistics section of the GO website. (Among those findings: Despite multiple mobile-friendly options designed especially for the event, nearly half of the 6,100+ participants chose to simply write down studio numbers throughout the day and check-in via the project website once back home, surprising project coordinators.) The website also provided a forum for participants to discuss (in real time and afterward) what they did and did not like about the process, share stories from their studio visits, learn about nominated artists, receive updates on the creation of the exhibit, and provide reactions to the final exhibit itself.

The exhibit has been criticized by some for not aptly representing the rich artistic quality Brooklyn holds, and is generating commentary on the age-old curatorial question of who should decide what constitutes “good” art. While a worthwhile debate, it seems to belie the larger point of the project: to expose people to the creative process, and ideally, to facilitate a better understanding of it. On that score, GO appears to have succeeded mightily. As project coordinators tagged entries in the Shared Stories section of the website, one of the most frequent themes to emerge was that of discovery. It seems that by opening studio doors, inviting people to participate in the curatorial process, and sharing reactions online, GO fostered meaningful interactions among artists, voters, volunteers, and museum staff, and in the process, created an innovative approach to engage audiences in the arts.

This Exquisite Forest: A Collaborative Project from Google Chrome and London's Tate Modern

Perhaps you played the French Surrealist game, ‘The Exquisite Corpse,’ in grammar school using the week’s vocabulary words or at a sleepover,  where someone inevitably managed to take the game in an inappropriate direction (wasn’t me, I swear).

If you do not recognize the creative exercise by its proper name, you will by its concept: a person begins a sentence or drawing on a piece of paper, covers their creation, passes the paper to the following person, and so the game continues until all participants have contributed. The final ‘masterpiece’ is often a comical, nonsensical, and potentially inappropriate, Dadaist anti-creation.

where someone inevitably managed to take the game in an inappropriate direction (wasn’t me, I swear).

If you do not recognize the creative exercise by its proper name, you will by its concept: a person begins a sentence or drawing on a piece of paper, covers their creation, passes the paper to the following person, and so the game continues until all participants have contributed. The final ‘masterpiece’ is often a comical, nonsensical, and potentially inappropriate, Dadaist anti-creation.

In July, Google’s Creative Lab teamed up with London’s Tate Modern Museum and launched the online collaborative project, “This Exquisite Forest.” Borrowing the game’s concept from the Surrealists, “This Exquisite Forest” enables users to draw or animate their own short animations (using Google Chrome browser) based on the initial “seeds” created by the artists Miroslaw Balka, Olafur Eliasson, Dryden Goodwin, Ragib Shaw, Julian Opie, Mark Titchner, Bill Woodrow, and Film4.0’s animators. One difference between the Surrealist’s version of the game and this project is the fact that online participants will have access to what was contributed before their own addition (as opposed to the Surrealist game where each participant's contribution is covered before moving on).

[embed]http://www.youtube.com/watch?feature=player_embedded&v=nnhJ1841K-8[/embed]

As users add their own animations and visual narratives using a web-based drawing tool, “the videos dynamically branch out and evolve, forming multiple new visuals.” From this idea- of initial videos or “seeds” planted by Tate’s artists- and the additional sequences branching out to create trees, this collaborative online project was coined “This Exquisite Forest.”

The project exists both in the digital realm and in the physical world. Large-scale projections of the best of the online contributions are displayed in the Level 3 gallery of the Tate Modern. In-house visitors have the opportunity to view the animations and contribute their own additions using digital drawing stations in the gallery.

“This Exquisite Forest” does three things expertly:

1) Allows museum-goers and web-users to become creators and curators, not just passive consumers of art

2) Provides a forum for the global, online community to collaborate creatively

3) Markets Google’s web browser Chrome, Google App Engine, and Google Cloud Storage

The physical installation at the Tate will run until January 2013 (approximately).

The Space: A Summer of English Arts on a New Experimental Platform

This Olympiad summer, the arts in the UK will be consolidated onto a single online platform called The Space. What’s more? The content on The Space is being provided for free! There’s room, or more fittingly, seats for all, at venues such as the World Shakespeare Festival or Yayoi Kusama’s Obliteration Room at the Tate.

“The Space is a new way to access and experience all of the arts – for free.Available on computer, tablet, smartphone and connected TV, The Space invites you to take part in the biggest summer of arts the UK has ever seen, whenever you want it and wherever you happen to be. ”

The Arts Council England in partnership with the BBC created The Space as a way for people from all over the world to experience the country’s rich and dynamic arts scene. In effect, a summer of English arts to all! (Albeit without the English summer and its cool Constable Skies). So The Space is certainly something to look forward too because it will feature some of the UK’s best theatrical productions, dances, musical performances, art exhibits, poetry readings, along with content that has been specifically created for the platform.

The Arts Council England in partnership with the BBC created The Space as a way for people from all over the world to experience the country’s rich and dynamic arts scene. In effect, a summer of English arts to all! (Albeit without the English summer and its cool Constable Skies). So The Space is certainly something to look forward too because it will feature some of the UK’s best theatrical productions, dances, musical performances, art exhibits, poetry readings, along with content that has been specifically created for the platform.

Through the course of the summer, the performances staged in theatre, dance, film, and music will be showcased via recordings and live streaming while exhibitions at museums and galleries will be presented via behind-the-scenes footage, photographs, and interviews with artists and curators. The Space will also feature experimental and interactive digital art that can be experienced on the platform itself. Finally, for poetry and literature, there will be a variety of formats, including podcasts, poetry readings, and interactive audio-visual timelines such as the 60 Years in 60 Poems.

While live streaming and online exhibits aren’t entirely new to the performing or visual arts, the presentation of all the arts, all at once, and in one place, is certainly a novelty. As such, The Space is truly remarkable because it is no ordinary task to fit an entire country’s arts scene onto a single platform! If other countries too made their arts available on interactive, well designed platforms, the internet would surely be a destination in itself. Perhaps the introduction of The Space suggests that it already is?!

The Space also signals another significant trend; the quality of arts being made available online continues to improve. Whether it is in opera, film, or even, educational art history, we are privy to some great material. At the same time, the problem with the online format is that there are times when our Google searches are less than serendipitous and our social networks less than social. On such days, we miss out on a lot of online events, projects, and experiments.

Yet on The Space, what will remain certain is most certainly the art. And at the end of each adequately sunny day across the Atlantic, the platform will be populated with new content for visitors to see, hear, read, and experience. Moreover, the content on this living library of the arts will be available until October. After that, it will be time, once again, to continue our search for the arts on the virtual infinity of the internet (The outer Space).

Best Practices in the Cloud: Creating Collaborative Communities in a Common Virtual Space

Slot Shelters is an international, design conversation between young students exploring the fabric and identity of their communities—and sharing their findings and designs with their peers across the globe.

their findings and designs with their peers across the globe.

A youth building and design project leveraging traditional and online cloud tools to create a global dialog around pattern, community identity and local bus shelter needs. Locally in San Jose, the Slot Shelters project aims to instill a vision of aesthetic possibilities and anchor Silicon Valley with a sense of place.

Specifically, students address the needs of their local community's bus shelters. By creating models using cardboard and pattern cards, the students design patterns that reflect the identity, needs and environment of their community. These physical models are then transformed digitally and refined using Google SketchUp. They are saved to a Google SketchUp warehouse and shared internationally with other participating students and schools.

Why Bus Shelters? Bus stops are existing hubs in our communities. Sometimes they have shelters over them and sometimes they do not. How can you creatively re-envisioned shelters so that these waiting spots become something more for your community? How can the bus shelter you create address contemporary needs of your community?

In the process of creating and drafting these designs, students become more aware of their visual environment, more in touch with the needs of their local community, and more familiar with the design prototyping process. The digital component to the project includes 3D, digital bus shelters in a shared Google SketchUp warehouse, a downloadable online ISSUU Slot Shelters Kit, and a library of design/pattern cards for other users to print out and utilize in the and construction of their own structures.

[embed]http://youtu.be/zeonh6VKMvQ[/embed]

Currently, participating students are 4th, 5th and 6th graders from Azerbaijan, Hawaii, Utah, Washington State, San Jose and Cupertino. In September, with the launch of the Seeking Shelter Design Challenge at the 2012 ZERO1 Biennial (a showcase of "contemporary work at the nexus of art and technology" in Silicon Valley), students will have the opportunity to submit their designs for official judging.

IMAGINE how a bus stop could be designed to renew, refresh, and connect people. Would you put in a mini community garden box? Solar cells? Bookshelves for informal book sharing? A small business kiosk?

BUILD your vision of a multipurpose bus shelter. Use slotted notecards. Use Google SketchUp.

SHARE your thoughts with us. Share concept physical models as images via Flickr or Picasa. Make a refined model in Google SketchUp and share to the “seeking shelter” 3D warehouse collection.

What does this project do so well and how can organizations learn from it?

-Collaboration and sharing: Google SketchUp (and other Google services) helps local and static projects become global and dynamic interactions

-Experiential learning in the physical realm: the Slot Shelters project begins in the physical realm, laying a foundation for the understanding of design principles and techniques before moving into the virtual realm

-Establishing communities in the virtual realm: As students build their bus shelters using Google SketchUp, they annotate each design decision. Shared online, students from across the globe involved in the product can add designs and more bus shelters to the virtual community to reflect the fibers and identity of their own environment

-Pragmatic design training: Students are given basic training with a tutorial on Google SketchUp, introducing them to the tools available, providing them with the appropriate design vocabulary and elevating their comfort level with building 3D structures in a virtual environment

-Application of project in the real-world: An installation of a conceptual bus shelter will be showcased at the 2012 ZERO1 Biennial. The public will have the opportunity to experiment with the design cards and design process by adding components to the model and working collaboratively.

Following the model of “imagine, build and share,” arts organizations can incorporate applications like Google SketchUp and VoiceThread in their educational programming and community outreach initiatives (click here for a beautiful graphic of the goals and outcomes for the project). By engaging the public in the cloud, projects and ideas become more dynamic, impactful and even international.

Love this project, love the dual-approach (physical and virtual design), and love the effort to increase awareness of the visual environment!

Canal Educatif: Art History Like You've Never Seen Before!

On YouTube, if you unearth past the layers of apocalyptic cats, nyan cats, evil cats, scary cats, and sneaky cats, you’ll find content that can actually educate you! A double rainbow for erudition! We have all heard about the instructional simplicity of Khan Academy and the brilliance of Ted-Ed, but there’s an equally fantastic channel for Art History buffs that truly deserves some viral appreciation: Canal Educatif à la Demande. Canal Educatif (educational channel) is a French co-operative project. Our aim is to produce a unique series of high-quality educational videos and make them available free of charge to young people and adults.

Since 2007, Canal Educatif (CED) has produced investigative-style documentaries on Art History, Economics, and Sciences and Innovation. Tristement, only the Art History section is available in English and it includes documentaries on works by Holbein, Delacroix, Poussin, and Rodin. But it is clear that the quality of these videos far succeeds their quantity! For example, in Delacroix’s Liberty Leading the People, the documentary explores why Delacroix, an aristocrat, would paint the very ideal he opposed and even feared? And why did Rodin leave his iconic sculptural gateway, The Gates of Hell, unfinished? Why was it never cast in bronze? These are just some of the questions answered in the highly informative series of documentaries produced by CED.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yFu3aJgkYkU

The organization has also explored a new avenue in the dissemination of Art History; the Google Art Project. In a YouTube series called Art Sleuth, CED has created short, detective style explorations of some of the gigapixel paintings on the Art Project. In these clever, 10 to 15 minute episodes, the nitty gritties of close observation reveal that in art too, the devil is in the details ; what seems to be a touching portrait of Marie Antoinette and her children, can emerge as thinly veiled attempt at false benevolence and humility. Coincidentally, there are some works in which there is literally (and figuratively), a Devil in the details.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gjcR90M8of4

To cover its production expenses, CED relies on micro-donations made to their website. So if you’d like to learn more about Manet’s A Bar at Folies Bergères, do make a contribution! Here’s hoping that Kickstarter will soon be launched in Europe because CED’s projects (Filmmaking) seem ideal for the crowdfunding platform. In the meantime, there’s a lot of content offered by CED on both YouTube and on its website. You certainly won't miss the repetitive babbling of nyan cats after having watched Manet’s In the Conservatory or Rembrandt’s The Prodigal Son. Let the sleuthing begin!

The Google Cultural Institute

Once a search engine for the curiously puzzled, the Google of today is not only a superior resource gateway but also a vast and interconnected information hub. When in doubt about your train of thought, just hop on aboard the Google express. Even for doubts verging on the impossible; search for walking directions from the Shire to Mordor on Google Maps and you are admonished that “one does not simply walk into Mordor.”

The dangers of Sauron aside, today Google can just as easily claim that one does not simply stop googling. It is now a verb, a translation service, a virtual wallet, a communication and storage platform, a social network, and more recently, a cultural institute.

“The Google Cultural Institute helps preserve and promote culture online. With a team of dedicated engineers, Google is building tools that make it simple to tell the stories of our diverse cultural heritage and make them accessible worldwide. We have worked with organisations from across the globe on a variety of projects; presenting thousands of works of art online through the Art Project, digitising the archives of Nelson Mandela and showcasing the Dead Sea Scrolls.”

Of the initiatives of the Google Cultural Institute, the Art Project and the Dead Sea Scrolls have received the most amount of attention. As such, we opted to take a look at some of the other projects that are changing the landscape (quite literally) of online cultural preservation.

Nelson Mandela Digital Archives Project

In 2011, the Nelson Mandela Centre of Memory partnered with Google to digitize and disseminate the archives of Nelson Mandela. The collaboration has resulted in a visually engaging timeline of Nelson Mandela’s life, populated with photographs, diary entries, letters, and excerpts from his autobiography. The site is worth a visit because it both explains and celebrates the enduring legacy of the South African statesman.

In 2011, the Nelson Mandela Centre of Memory partnered with Google to digitize and disseminate the archives of Nelson Mandela. The collaboration has resulted in a visually engaging timeline of Nelson Mandela’s life, populated with photographs, diary entries, letters, and excerpts from his autobiography. The site is worth a visit because it both explains and celebrates the enduring legacy of the South African statesman.

World Wonders Project The World Wonders Project is perhaps the next iteration of the Street View mode in Google Maps. In a partnership with UNESCO, the World Monument Fund, and Getty Images, the project “allows you to navigate virtually around some of the most important, historical and beautiful world heritage sites through panoramic street-level images, experiencing these places almost as if you were there.” The project is an impressive window to the world but is perhaps most suited to educational purposes.

La France en relief

When the Grand Palais in Paris organized an exhibition showcasing 17th and 18th century relief maps of fortified towns in France, Google helped render seven of those models in 3-D. As such, seven fortified towns in France were built anew, in all their artisanal detail, on Google Earth. Furthermore, the reach of the exhibition was no longer limited by the very concept being showcased; geography.

La France en relief

When the Grand Palais in Paris organized an exhibition showcasing 17th and 18th century relief maps of fortified towns in France, Google helped render seven of those models in 3-D. As such, seven fortified towns in France were built anew, in all their artisanal detail, on Google Earth. Furthermore, the reach of the exhibition was no longer limited by the very concept being showcased; geography.

La Pavillon de l’Arsenal (Paris Center for Architecture and Urbanism) Just as Google re-envisioned the past at the Grand Palais, at La Pavilon de l’Arsenal, it envisioned the future. Visitors were given a chance to explore the urban landscape of Paris of 2020 through “the first ever 48 screen interactive Liquid Galaxy display, which featured “3D models of the buildings, designed but not yet built, by architects such as Patrick Berger and Jacques Anziutti, Jean Nouvel and Rudy Ricciotti.”

Yad Vashem

Google has helped digitize the vast archives of Yad Vashem, which is “the world center for documentation, research, education and commemoration of the Holocaust.” Through a technique called optical character recognition (OCR), Google has enabled families to search for both documents and images belonging to their relatives.

Here is an example given by Google: “To experience the new archive features yourself, try searching for the term [rena weiser], the name of a Jewish refugee. You’ll find a link to a visa issued to her by the Consulate of Chile in France.”

Google has helped digitize the vast archives of Yad Vashem, which is “the world center for documentation, research, education and commemoration of the Holocaust.” Through a technique called optical character recognition (OCR), Google has enabled families to search for both documents and images belonging to their relatives.

Here is an example given by Google: “To experience the new archive features yourself, try searching for the term [rena weiser], the name of a Jewish refugee. You’ll find a link to a visa issued to her by the Consulate of Chile in France.”

So there you have it, some of the Google's lesser known projects. Looks like culture is out there, quietly populating the internet. One need only google it.

Confirmed by Nonprofit Quarterly: Generating online content is NOT optional

Just when you thought your nonprofit’s résumé was updated and accurate, it is time to add another job responsibility: publisher.

As recently reported by Joe Waters with Nonprofit Quarterly, “Nonprofit employees have always had to wear a lot of hats: fundraiser, marketer, grant writer, etc. Here’s one more you need to get used to wearing: publisher. Fortunately, this additional job has a real benefit, as it engages current and potential supporters with useful, interesting and credible information that directly drives donor support.”

The key to generating and publishing online content is to be timely, stay relevant, and to “inform, educate and inspire.” Unlike an advertisement, online content allows followers to interact with the information, contribute and hear/see/participate in the organization’s story.

While many of our followers have already identified and addressed the publishing aspect of their nonprofit work, Nonprofit Quarterly offers three reasons why generating and publishing online content is no longer an option for small nonprofit organizations.

1) “It’s part of being a top nonprofit brand”

Build community around your brand and cause by publishing engaging, inspiring, visually compelling and relevant content (and just to clarify, that is NOT your monthly newsletter).

2) “You need to stand out”

It’s a dog-eat-dog world out there. We are all on Facebook, we all have Twitter accounts for our organizations, many organizations maintain blogs—it’s time to step up your online content, videos, podcasts, links, downloadable and free content, etc. Simply having an online presence is no longer enough. Though we prefer to think we are not competing with other nonprofit organizations, the truth of the matter is, we are.

“With more and more nonprofits coming online each year, content is a key tool in separating your nonprofit from the pack. This is especially important as people search for your nonprofit on Google, Bing and Yahoo. Several factors are important in how search engines rank and deliver search results, but one thing is clear: if you don’t produce high quality content and links, online searchers won’t find you. Period.”

3) “You can’t just do good work anymore”

Nonprofit to nonprofit, many of us share similar, philanthropic visions for our organizations. Because of this, the general public has its pick of relevant, benevolent, and noble organizations to support and fund. So now that you can’t claim your work is MORE important or MORE charitable than the next nonprofit’s, how do you get that donor’s attention and dollar? Answer: tell your story in a compelling way, manipulating the resources the web provides. Facebook photo albums, Twitter contests, IncenTix by ShowClix, Pinterest, podcasts, infographics – these and the resources we feature here on Technology in the Arts can help you do just that.

Am I suggesting all nonprofits abandon the newsletter and print medium in this competitive, nonprofit landscape? Of course not. YouTube channels and 140-character-Twitter-contests are wasted on my parents. They look for the newsletter in the mail every month (but continue to impress me when they sign up to receive them by e-mail…way to go, Mom and Dad, makin' me proud).

Publishing online has become increasingly dynamic, visual, and allows for a voice in 3-D; a voice that speaks louder, in more colors, and more emotionally than the traditional newsletter printed and mailed for years and years. Storytelling has moved online with a worldwide audience waiting to feel emotionally compelled, connected, and stimulated by the content your organization generates and publishes.

The Google Art Project Welcomes You to the White House

Ever wanted to take a tour of the White House? Well now you have a chance, and you can do it all from the comfort of your living room.

The Google Art Project, a site devoted to presenting high resolution photographs of hundreds of works of art and museum tours from some of the finest museums in the world, including the Palace of Versailles, the Van Gogh Museum and the Metropolitan Museum of Art, has unveiled its latest project, a captivating look inside the world’s most famous residence, the White House.

Ever wanted to take a tour of the White House? Well now you have a chance, and you can do it all from the comfort of your living room.

The Google Art Project, a site devoted to presenting high resolution photographs of hundreds of works of art and museum tours from some of the finest museums in the world, including the Palace of Versailles, the Van Gogh Museum and the Metropolitan Museum of Art, has unveiled its latest project, a captivating look inside the world’s most famous residence, the White House.

As part of what the White House calls its “commitment to opening the doors of the White House to all Americans,” the site primarily does two things. First, it presents images of dozens of paintings and works in art in stunning high resolution quality; and secondly, my favorite part, it offers a 360-degree view of many of the “public” areas of the White House, giving you your own personal tour!

The White House is the latest location added to Google’s Art Project website, which has steadily grown in recent months by adding some of the top museums in the world to its collection. It really is a site to behold and a must visit for arts lovers everywhere; by taking some of the world’s best collections and putting them online free of charge for the world to see, it really does represent one of the best ways to merge technology with the arts to generate enthusiasm and excitement for the stunning works of art that are now viewable in all their high definition glory.

For the paintings and works of art themselves, Google features what they call a “gigapixel” camera that offers an extremely high resolution look at some of the most famous paintings in the White House collection, including Gilbert Stuart’s famous portrait of George Washington. Viewers can zoom in and examine the paintings in EXTREMELY close detail, all the way down to the brushstrokes, just as you would if you were to view them in person, right?

You’ll find hundreds of paintings, sculptures, pieces of furniture, and more available for view. You’ll also find a portrait of almost every former president as well. Some of my favorite presidential portraits, which I have seen before on either book covers, in print or elsewhere, were immediately noticeable and fascinating to view up close and in so much detail. Some of my favorites include Aaron Shikler’s portrait of John F. Kennedy, John Singer Sargent’s portrait of Teddy Roosevelt, George P.A. Healy’s portrait of a sitting Abraham Lincoln, and last by not least, John Trumbull's portrait of my favorite founding father, Alexander Hamilton.

The coolest part of the site however, if you’re like me, is the virtual tour. In recent months, Google has made headlines by starting to take their Street View cameras indoors to start photographing businesses and places of interest to add to its Google Maps site. What Google has done here is to take those Street View cameras inside the White House and presented a “museum view” of the public spaces inside. Here is where you can walk around and give yourself a tour of two floors of the White House, seeing sights like the East Room (where indoor press conferences are usually held) and the China Room, where presidential china collections dating back to the 18th century are held.

Not everyone will have the chance to visit Washington and take the White House tour (which is a hard ticket to come by, and even if you can get on the list, usually requires a several months long wait), but thanks to Google, we now have the next best thing, viewing many of the sights you would see on a tour on your computer screen.

This may be one of the few things everyone can agree on when it comes to the White House: having an opportunity to view the magnificent works of art from the White House collection in such high resolution is a welcome treat, and worthy of praise. I encourage everyone to check out the site and go exploring!

BMW Tate Live: An Online Space for Performance Art

On March 22nd, Jérôme Bel, a french choreographer and dancer, performed in an unknown room at the Tate Modern to an equally unknown audience. Odd as it may seem, there was not a single audience member present in the room. Those who were watching the performance were watching it online, inhabiting a newly unveiled virtual space called the BMW Tate Live: Performance Room.

“The BMW Tate Live: Performance Room is an innovative series of performances broadcast viewable exclusively online around the globe, as they happen.”

“The BMW Tate Live: Performance Room is an innovative series of performances broadcast viewable exclusively online around the globe, as they happen.”

It is the outcome of “a partnership between BMW and Tate, which focuses on performance, interdisciplinary art and curating digital space.” Jérôme Bel’s performance was the first in a series of five online performances that will run through July, featuring the work of artists Pablo Bronstein, Harrell Fletcher, Joan Jonas and Emily Roysdon.

The idea of an exclusively online performance is perhaps more innovative than the technology being used to showcase it, a Youtube channel and a single camera. Catherine Wood, the Tate’s curator of Contemporary Art and Performance, explained in article on Artinfo that they wanted to transmit the work in the “simplest means” and a single camera essentially acted as the “fourth wall” of the performance space.

Additionally, the integration of Twitter, Facebook, and Google+, allows the audience to write comments during the performance and later pose questions to the curators and artists. This allows for the creation of a virtual audience that is connected in real-time through reactions, thoughts, and the Twitter phenomenon, hash tags (#BMWTateLive). Access to these real-time reactions from around the world truly is phenomenal and wouldn't be possible in a traditional setting. The trade-off, however, could be the evolution of an audience that tweets more than it sees, and comments more than it listens.

When asked by Artinfo on whether this online medium may take something away from a live performance, Catherine Wood replied that there has already been much debate “about how much performance documentation is the work and how much it is a record of the work.” But she added that “Live-ness is inherently mediated by technology in the world we live in now. There will always be a place for just a person in a room and a live audience, but I think this is part of the evolution of performance art that we can't ignore."

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kf77fzBOoNo

For those afraid of testing the niche waters of contemporary performance art, the increased accessibility and chance to experience an unfamiliar genre through YouTube cannot be ignored. A few swells of interest, a little online momentum, and the waters of performance art will seem a lot less murky or impenetrable. As of the 4th of April, Jérôme Bel’s performance has been viewed 862 times, but that doesn't take into account the number of people who watched it live.

In order to participate in the ongoing conversation, a viewer must to tune into the Tate's website or YouTube channel as the performance is being broadcast. Since the remaining performances are scheduled to take place at 20.00 hours (London), they will be most accessible to audiences in North America (~15.00 hours) and Europe (~21.oo hours), with the exception of a few arty insomniacs in Asia (~1.00 hours). But for those who may be asleep or at work, each performance is archived and uploaded to YouTube.

The next performance is scheduled for April 26 and features Pablo Bronstein, an Argentinian artist who uses “architectural design and drawing to engage with the grandiose and imperial past of the built environment.” In his performance, Bronstein “will work with up to ten dancers to create a baroque trompe l’oeil stage set that exaggerates the perspective within the Performance Room.”

If time permits, tune in to BMW Tate Live for Pablo Bronstein! You may lose your sense of perspective, but find a deeper understanding and appreciation for performance art. If time doesn't permit, don’t miss out on the opportunity to watch these performances on YouTube at a later date.