Introduction

Theatre live broadcasting has existed across various media for nearly a century. In its early days, it was delivered through radio and television. In the 21st century, advancements in technology enabled broadcasts on large cinema screens. During and after the COVID-19 pandemic, however, lockdowns and shifts in audience behavior appeared to redirect attention back to small screens. This research explores the meaning of “liveness” and whether live theatre broadcasts, sometimes costing up to $3 million, are worth the investment. The study includes a historical overview of theatre broadcasting, examines academic, audience, and industry perspectives on liveness, analyzes the purpose and impact of these broadcasts, and considers future directions, with a focus on developments over the past two decades.

Definitions

Broadcasting refers to the transmission of media to a broad audience. Types of broadcasting include radio, television, satellite, cable, and the internet. Unlike pre-recorded broadcasts, live broadcasting is characterized by the “temporal simultaneity of production and reception” and “experience of event as it occurs” (Auslander, Liveness, 61). In the context of this study, live theatre broadcasts encompass live radio, live television, live movie theatre broadcasts, and live internet broadcasts.

While some argue that live streaming is a form of broadcasting, this study focuses on one-way, real-time transmissions that do not allow for direct audience interaction. Because live streaming typically delivers content on a one-to-one basis and enables interactive experiences, it falls outside the scope of this study.

Figure 1: National Theatre Live cameras filming The Book of Dust

Source: The Stage

A Historical Overview

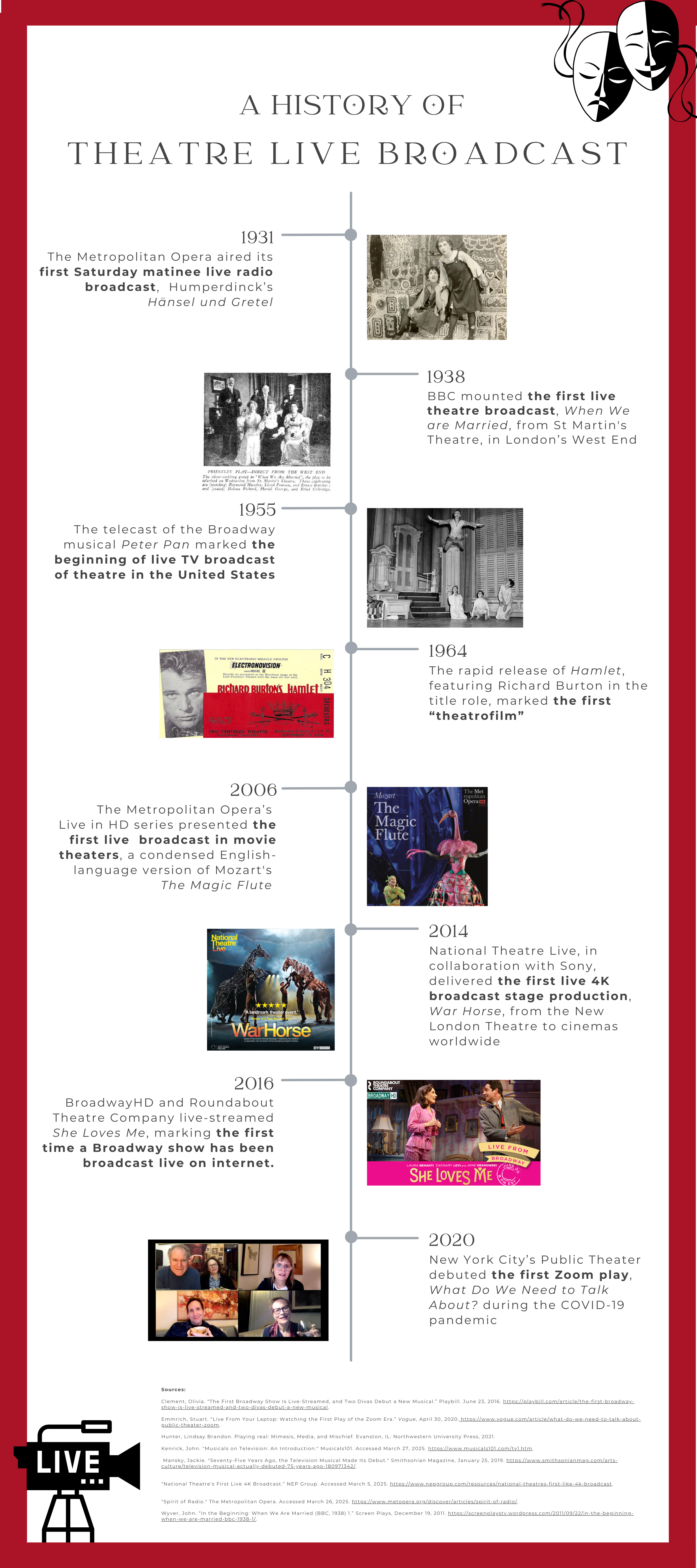

Theatre live broadcasting is not a new phenomenon. As early as December 25, 1931, the Metropolitan Opera began its first season of Saturday matinee radio broadcasts with Humperdinck’s Hänsel und Gretel, featuring Milton Cross as the announcer.

In 1938, the BBC mounted the first live theatre broadcast on TV, When We Are Married, from St Martin's Theatre in London’s West End. More playwrights began making their television debuts, but TV production was interrupted by the outbreak of the Second World War. Regular BBC broadcasting did not resume until 3 PM on June 7, 1946.

In the 1950s, American commercial broadcast television and radio networks such as National Broadcasting Company (NBC), CBS Broadcasting Inc., Dumont, and later American Broadcasting Company (ABC), began live broadcasting musicals. On June 15, 1953, Ford Motor Company celebrated its 50th anniversary with a live television spectacular featuring a joint performance by Ethel Merman and Mary Martin, directed by Jerome Robbins. Broadcast by CBS and NBC, the show drew 60 million viewers and nationwide acclaim. In 1955, the Broadway musical Peter Pan was broadcast live by NBC. The performance was adapted by the staged musical for TV and was the first full-length Broadway musical live on color TV. This trend peaked in the 1950s-60s.

A historically significant moment in theatre broadcasting occurred in 1964 with the stage production of Hamlet, starring Richard Burton and directed by John Gielgud. Though not a live broadcast, the team aimed to simulate one by rapidly filming and releasing the production in movie theaters nationwide. This allowed audiences across the U.S. to experience a Broadway show as a “theatrofilm” for the first time. The recording was shown only four times over two days, intentionally reflecting the ephemeral nature of live performance.

Decades later, as the 21st century began, many organizations and companies recognized the potential of theatre live broadcasts. In 2006, the Metropolitan Opera launched the first Live in HD broadcast. Three years later, in 2009, National Theatre Live (NT Live) debuted, capturing performances from some of Britain’s most prestigious stages and screening them live in movie theatres worldwide. With high-definition video and surround sound, NT Live has reached over 12 million viewers.

Similar models followed: the Royal Shakespeare Company’s Live from Stratford-upon-Avon series launched in 2013; the Kenneth Branagh Theatre Company began its live broadcasts in 2016; and BroadwayHD, while primarily focused on recordings of Broadway and Off-Broadway productions, aired its first live Broadway broadcast that same year. Nonprofit theaters like HowlRound also embraced the format, live-broadcasting performances on HowlRound TV, alongside many smaller theatres and organizations experimenting such models (Hunter, Playing Real, 6-7).

The COVID-19 pandemic accelerated the rise of live theatre broadcasting. Many regional theaters began exploring live broadcasts as a way to stay connected with their audiences and sustain live performance despite the high costs. The League of Live Stream Theater, a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization founded in 2022, is dedicated to delivering live performances to audiences around the world in real time through live streaming. Its nonprofit structure allows it to receive support from stakeholders who value the importance of live theatre broadcasting.

Zoom theatre also emerged in both professional and educational contexts. The Public Theater premiered the first Zoom play, What Do We Need to Talk About? by Richard Nelson, who adapted his Michaels series to a virtual setting. In 2021, Isaiah Matthew Wooden directed The Lathe of Heaven via Zoom at Brandeis University. However, since Zoom allows for interactive, two-way engagement, it falls outside the scope of this study.

Figure 2: A Timeline of Theatre Livestream Broadcast.

Graphic by Author.

Does “Liveness” Matter in Theatre?

The significance of liveness in theatre has been debated since the 1990s. Peggy Phelan argues that the ontology of performance lies in its resistance to mass reproduction and its present moment, in other words, its “liveness” (Phelan, 5-10). She asserts that performances cannot be saved, recorded, or documented, and that any attempt at reproduction is seen as a betrayal of their ontology (149).

In Liveness: Performance in a Mediatized Culture (2008), Philip Auslander challenges the belief that audiences are drawn to theatre for its so-called "magic" or the unique "energy" created between performers and spectators, asserting instead that the concept of "liveness" is itself a construct of mediation (2). He critiques the notion of a “competitive opposition” between the live and the mediatized, contending that they are interdependent (11). Auslander thus questions the assumed necessity of a physically present audience in theatre, arguing that the elevated value placed on in-person live performance reflects the anxiety of theatre practitioners and audiences in a cultural context that privileges the mediatized and marginalizes the live (46). He further suggests that the primary distinction between live and mediatized performances lies in the social prestige afforded to those who can claim they attended a live event (66). Moreover, Auslander argues that live performances can be replaced by media, not only because television was invented, in part, to replicate theatre’s “immediacy” through live studio broadcasts (23), but also because the notion of “uniqueness” is not exclusive to live events. He notes that even recorded broadcasts possess elements of uniqueness, as physical and digital media deteriorate over time and with each use, making every viewing subtly different (49-50).

“In a very literal, material sense, televisual and other technical reproductions, like live performances, become themselves through disappearance.”

Thus, it can be deduced that Auslander believes live broadcasts, and even recorded broadcasts, can preserve the same level of theatricality as live performances in the theater. Over the years, other scholars have proposed both similar and opposing ideas, but Auslander's theories have gained significant recognition and continue to be frequently cited in academic research and discussions.

Figure 3: National Theatre Live cameras filming All's Well That Ends Well

Source: Nesta

The Audience

According to Bruce McConachie, even in the most traditional proscenium theatre, without breaking the fourth wall, theatrical engagement functions in a reciprocal way. While the artists deliver the performance to the audience, the audience does not merely passively observe but actively interprets the work (McConachie, 2). Therefore, while the discussions above are valuable, it is equally important to consider what the other side, the audience, thinks about “liveness.”

In a small exploratory study conducted by Matthew Reason in 2004, seven University of Edinburgh students attended a live performance of Olga and participated in group discussions after the show. Without being prompted about “liveness,” they naturally reflected on the actors’ presence, the intimacy of the space, the difference in their experience due to seating, the unpredictability of theatre, and how these aspects contrasted with screens. Although the participants lacked formal training in drama and thus used little professional terminology, they engaged in validating or questioning each other’s impressions, building a collective memory of the event. While the result might lack universality due to the small sample size, it revealed the potential significance of “liveness,” offering insights that extend beyond theoretical definitions.

Reason’s other field study in 2006 showed that audiences, particularly younger or less experienced ones, perceived live theatre and screen-based media very differently. Not only did they experience theatre as a social activity, as Auslander suggests, but they also went through a heightened sense of engagement while seated in the theatre. The live nature of theatre, including the physical presence of actors, the unpredictability of performance, and the possibility of missing key moments, created a unique sense of urgency that significantly increased their involvement.

Figure 4: Pie chart showing audience excitement watching theatre live broadcasts. Source: 2011 Nesta Report. Creator: Author.

The two studies showed that liveness matters to audiences, as they recognized the presence, intimacy, and unpredictability of live theatre performances. Although live broadcasts cannot preserve all of these elements, real-time transmission may be able to spark audience excitement and devotion as it preserves the risks and vulnerabilities of live performances. Indeed, the 2011 Nesta report shows that 84% of NT Live audiences felt genuine excitement from watching a live cinema broadcast occurring simultaneously with the stage performance. Interestingly, audiences in movie theatre reported higher levels of emotional engagement than those who regularly attend live theatre.

These theories are supported by practice. In the development stage of live theatre broadcasting, industry practitioners largely treated live broadcasts as potential replacements for in-person performances, with the “live” component seen as crucial. In their early stages, the Met Opera Live in HD and NT Live emphasized the uniqueness and immediacy of their broadcasts, promoting them as compelling alternatives to physically attending the theater. Even the 1964 Electronovision Hamlet, which was not actually live, attempted to simulate a live experience through choices like preserving actors’ mistakes, rapidly releasing the film, and offering limited showings.

These strategies reveal a clear belief in the industry in the importance of capturing liveness when the performances were distributed to the audience in mediatized forms.

The preservation of theatrical liveness is also reflected in maintaining live theatre rituals. The Met provides partner venues with single-page cast sheets containing key casting details and a brief opera synopsis, also available digitally. NT Live and Live from Stratford-upon-Avon often go further, featuring interviews or plot introductions pre-show or during intermission, offering cinema-goers a unique experience.

What Theatre Live Broadcast Can Do - A Case Study of NT Live

The Purpose of Creating Theatre Live Broadcasts

Although generating revenue is always a consideration for live broadcasts, their primary purpose has been to make theatrical works accessible to a wider audience. As stated in the National Theatre’s 2021–22 Annual Review, the goal of establishing NT Live was to break down “geographical, access, and financial barriers.” Emma Keith, former Managing Director of Digital at the National Theatre, also emphasized in a recent podcast that the department was created to ensure as many people as possible could engage with culture and the arts. In NT Live’s 10-year anniversary video released in 2019, the mission was succinctly captured in the statement: “This is a theatre for everyone.”

Will Live Broadcasts Replace Live Performances?

Over time, scholars and practitioners shifted their mindset from treating live broadcasts as direct replacements for in-person performances. Sarah Bay-Cheng emphasizes that, regardless of how immediate the broadcasting process may be, live streams should not be seen as direct representations but rather as altered interpretations, or even “distortions,” of the original performance (Bay-Cheng, 39–40). After several successful seasons, leaders at NT Live moved away from viewing theatre broadcasting as a "second-class experience" and began to recognize it as a distinct and valuable form of theatrical engagement in its own right.

“We have become more confident in seeing NT Live as an experience on its own. No, it is not the same as being in the theatre and never could be. But we have seen that it can be an experience of artistic merit, and it can honour the integrity of the work and have a significant connection with audiences – it is not second-class, but a different experience.”

As Keith introduces, today’s theatre live broadcasts are designed to offer a high-quality but distinct experience from attending theatre in person. Much like live sports broadcasts, they provide audiences with a "moveable best seat," featuring multiple camera angles and views that are not possible from any single seat in the theatre. To achieve this, hundreds of seats are often removed, and the theatre is temporarily treated more like a television studio than a traditional performance venue.

Data suggests that live broadcasts serve as a complement to theatre performances rather than a replacement. According to the 2011 Nesta report, NT Live attracted a wider and more economically diverse audience than traditional theatre: about 25% of cinema viewers earned less than £20,000 annually, and the proportion of those earning under £50,000 was twice as high as that of typical theatre audiences. Rather than drawing audiences away from theatres, NT Live appealed to audiences in need of a more accessible way to experience theatre. In 2014, Nesta conducted further research using box office data from 54 UK performing arts organizations, covering 44 million tickets sold between 2009 and 2013, during NT Live's expansion. The findings showed no decline in local theatre attendance. In fact, areas within three kilometers of NT Live cinemas in London saw a 5% increase in the following year. Emma Keith also noted in the podcast that even post-COVID, no evidence links live broadcasts to reduced theatre attendance.

The Current State and Future Directions

The Current Business Model and Audience Behavior

The biggest and most well-known theatre live broadcast series, NT Live and the Met Opera Live in HD, choose to broadcast live in movie theaters. To cover the high costs of live broadcasting, NT Live has a mixed funding model, receiving funding from TV channels, philanthropy organizations, and other sponsorships. The Met Opera is also a nonprofit organization receiving contributions of various kinds to cover expenses. Yet, according to their FY 2023 Financial Statements, their Live in HD revenues remained well below the pre-pandemic level.

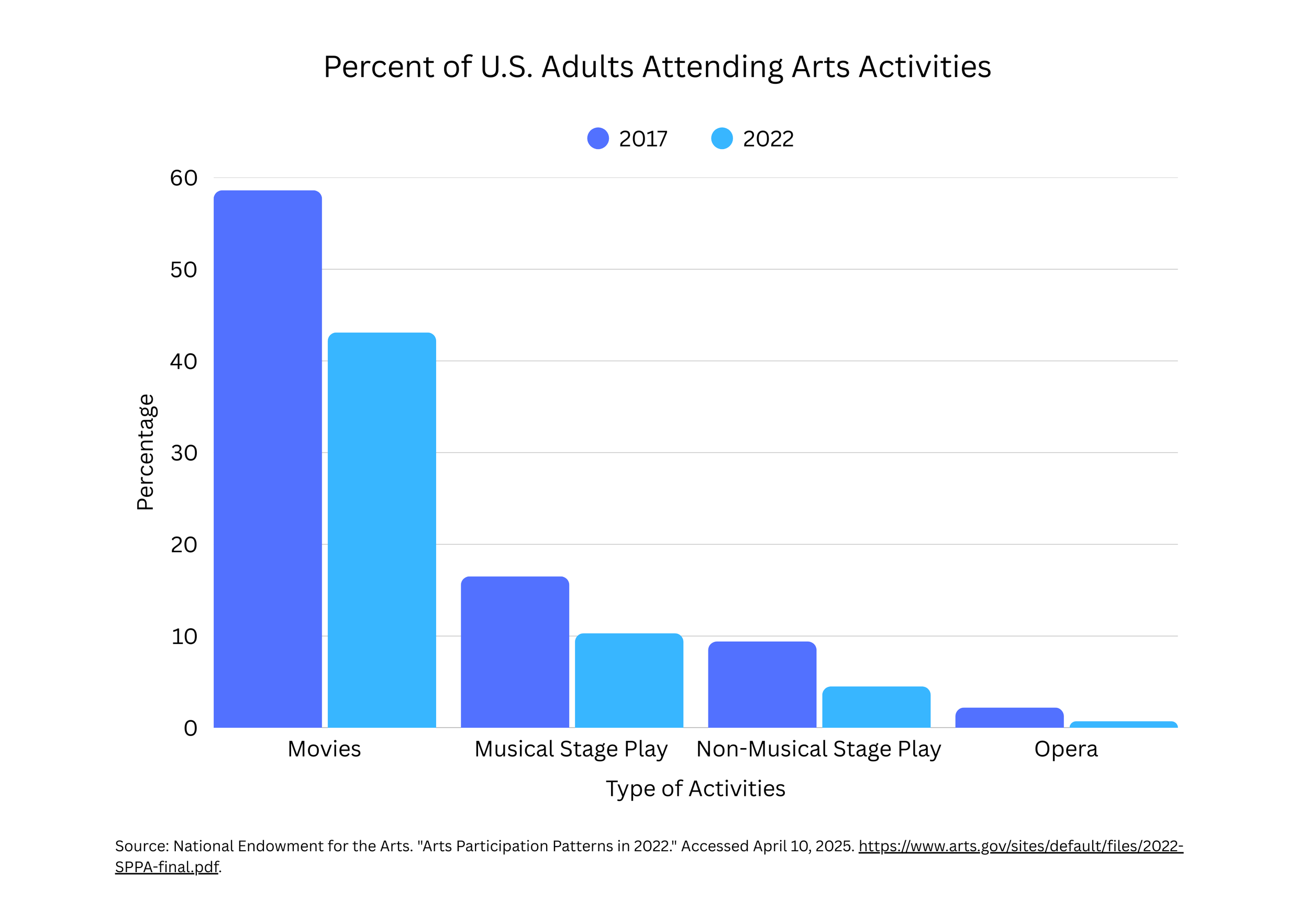

Figure 5: Side-by-side bar chart showing percent of US adults attending arts activities in 2017 and 2022.

Data Source: National Endowment for the Arts. Graphic by Author.

As shown in Figure 5, U.S. adult movie attendance dropped from 58.6% in 2017 to 43.1% in 2022, showing a 26% decline. This trend also affected attendance at musicals, plays, operas, and many other art forms. While some of this decline may be temporary due to the temporary closing of performing arts venues during the pandemic, long-term behavioral changes have emerged as digital content became far more accessible than before COVID-19.

Figure 6: Stacked bar chart showing US Entertainment Market and Pay TV Market.

Source: Motion Picture Association

More specifically, Figure 6 illustrates an overall decline in the entertainment market from 2017 to 2021. Physical, theatrical, and paid TV sectors all decreased, while the digital entertainment market grew from $14.0 billion to $29.5 billion, more than doubling in size.

Both the National Theatre and the Met Opera recognized this shift. NT launched NT at Home in 2020, and the Met introduced The Met: Live at Home in 2022. Additionally, nonprofit organizations like the League of Live Stream Theater now begins to provide real-time live performances to audiences through streaming.

Future Directions for Theatre Live Broadcast

As mentioned in the very beginning, theatre live broadcasts span several media types: radio, television, movie theaters, and the internet via computers and phones. Among these, movie theaters arguably offer the closest approximation to live theatre, mirroring the spatial relationship between audience and performers, the scale of the screen relative to a proscenium, and the shared experience of a communal audience. The smaller the screen, the closer the distance between the audience and the screen, and the smaller the crowd.

Since movie theaters appear to be the most effective medium for conveying the essence of a theatrical experience, despite the decrease in movie theater attendance, services like NT Live and Met Live in HD should not be replaced.

Yet, it is still essential for organizations offering theatre live broadcast services to stay up to date with audience behavior. In particular, understanding how different generations engage with various types of media can help these organizations better target desired audiences and break down barriers to access.

Figure 7: Bar chart showing average daily media use in the US in 3rd quarter of 2024, by medium.

Source: Statista.

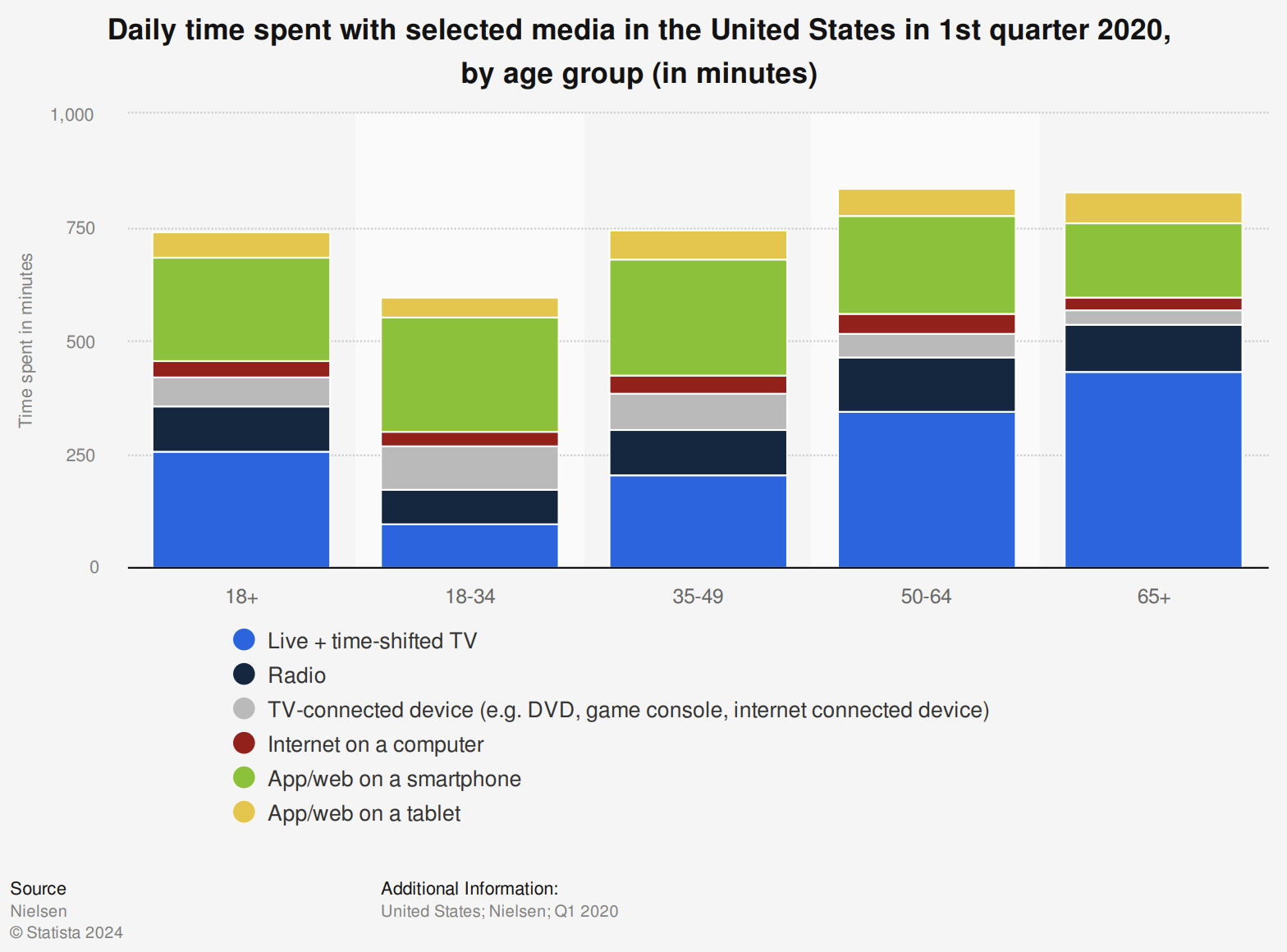

Figure 8: Stacked bar chart showing the average daily media use in the US in 1st quarter 2020, by medium and age group.

Source: Statista.

What is shown in Figure 7, the average daily media use in the US, is not surprising. Internet usage dominates, averaging 6.4 hours per day, followed by television (broadcasting and streaming) at 4.55 hours. Time spent on listening to radio broadcasts is around 1.03 hours, while podcasts take only 0.52 hours. Overall, the data shows a shift toward screen-based digital media, with traditional forms like radio and non-visual forms like podcasts receiving less attention. For organizations offering theatre live broadcasts, these insights emphasize the importance of digital platforms, especially internet, for audience engagement.

Figure 8 displays generational preferences in media consumption. Older adults (65+) spend the most time on media overall, particularly with TV. TV consumption decreases with age, with 18-to-34-year-olds spending the least time. App, web, and internet uses on smartphones, tablets, and computers are highest among the 18-34 and 35-49 groups. Radio shows consistent use across age groups. For live theatre broadcasts, targeting older adults through traditional media and younger audiences via app, web, and internet may lead to better outreach and engagement.

Final Discussion

The reason for conducting a case study on NT Live is the lack of publicly available data from many other organizations. Even the data used in this research is not entirely comprehensive, due to small sample sizes or datasets that cover broader media consumption rather than focusing merely on the performing arts. Nonetheless, the existing data already offers valuable insights into the potential future direction of theatre live broadcasts and how they can improve accessibility to a broader audience. It is therefore important for organizations and agencies to make arts-related datasets available to researchers, following the example set by other fields.

-

“A Short History of the Television Play.” Teletronic. Accessed March 4, 2025. https://teletronic.co.uk/television-history/a-short-history-of-the-television-play.

“About Us.” National Theatre Live. Accessed March 4, 2025. https://www.ntlive.com/about-us/.

Auslander, Philip, and Philip Auslander. Liveness: Performance in a Mediatized Culture. 2nd ed. London: Routledge, 2008. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203938133.

Bay-Cheng, S. (2007). “Theatre Squared: Theatre History in the Age of Media.” Theatre Topics, 17(1), 37–50. https://doi.org/10.1353/tt.2007.0001.

"Birth of Public Radio Broadcasting." The Story of Information, January 13, 2013. https://infostory.com/2013/01/13/birth-of-public-radio-broadcasting/.

Bosanquet, Theo. “Research Finds That NT Live Has ‘no Negative Impact’ on Regional Theatregoing.” WhatsOnStage, June 25, 2014. https://www.whatsonstage.com/news/research-finds-that-nt-live-has-no-negative-impact-on-regional-theatregoing_34856/.

"Broadcasting vs Streaming: What’s the Difference?" Castr, August 31, 2024. https://castr.com/blog/broadcasting-vs-streaming/.

Clement, Olivia. “How the Public Theater Reunited the Cast of The Apple Family Plays for a Zoom Play About COVID-19 and the Future of Theatre.” Playbill. April 29, 2020. https://playbill.com/article/how-the-public-theater-reunited-the-cast-of-the-apple-family-plays-for-a-zoom-play-about-covid-19-and-the-future-of-theatre?.

Clement, Olivia. “The First Broadway Show Is Live-Streamed, and Two Divas Debut a New Musical.” Playbill. June 23, 2016. https://playbill.com/article/the-first-broadway-show-is-live-streamed-and-two-divas-debut-a-new-musical.

"Consolidated Financial Statements, July 31, 2023 and 2022." Metropolitan Opera Association, Inc.. Accessed April 10, 2025. https://www.metopera.org/globalassets/about/annual-reports/met-opera-fy2023.pdf.

Emmrich, Stuart. “Live From Your Laptop: Watching the First Play of the Zoom Era.” Vogue, April 30, 2020.https://www.vogue.com/article/what-do-we-need-to-talk-about-public-theater-zoom.

“Emma Keith (National Theatre) on NT Live, Remote Audiences, Experimentation, Learning, Thinking about Value, Leadership, and the Importance of Pilots.” Digital Works Podcast, April 4, 2025.https://www.buzzsprout.com/841957/episodes/16903276-emma-keith-national-theatre-on-nt-live-remote-audiences-experimentation-learning-thinking-about-value-leadership-the-importance-of-pilots-and-more.

"Home." The League of Live Stream Theater. Accessed March 29, 2025. https://www.lolst.org/.

Hunter, Lindsay Brandon. Playing real: Mimesis, Media, and Mischief. Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Press, 2021.

Hunter, Lindsay Brandon "We are Not Making a Movie": Constituting Theatre in Live Broadcast." Theatre Topics 29, no. 1 (03, 2019): 15-27. https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/we-are-not-making-movie-constituting-theatre-live/docview/2295413840/se-2.

Kenrick, John. "Musicals on Television: An Introduction." Musicals101. Accessed March 27, 2025. https://www.musicals101.com/tv1.htm.

Kiruthika. “What Is the Difference between Live Streaming and Broadcasting.” Gudsho, August 11, 2023. https://www.gudsho.com/blog/live-streaming-vs-broadcasting/.

"Live in HD FAQ." The Metropolitan Opera. Accessed April 10, 2025. https://www.metopera.org/about/faq/live-in-hd-faq/.

Mansky, Jackie. "Seventy-Five Years Ago, the Television Musical Made Its Debut." Smithsonian Magazine, January 25, 2019. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/arts-culture/television-musical-actually-debuted-75-years-ago-180971342/.

Manvell, Roger, and Jorge A. Camacho. “Broadcasting.” Britannica, February 25, 2025. https://www.britannica.com/technology/broadcasting.

McConachie, Bruce A. Engaging audiences: A Cognitive Approach to Spectating in the Theatre. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2011.

Meyer-Dinkgräfe, Daniel. “Cold Dark Soft Matter Research and Atmosphere in the Theatre.” Body, Space & Technology 6, no. 1 (July 1, 2006). https://doi.org/10.16995/bst.173.

Meyer-Dinkgräfe, Daniel. "Liveness: Phelan, Auslander, and After." Journal of Dramatic Theory and Criticism 29, no. 2 (2015): 69-79. https://dx.doi.org/10.1353/dtc.2015.0011.

Motion Picture Association. "2021 Theme Report." Accessed April 10, 2025. https://www.motionpictures.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/MPA-2021-THEME-Report-FINAL.pdf.

National Endowment for the Arts. "Arts Participation Patterns in 2022." Accessed April 10, 2025. https://www.arts.gov/sites/default/files/2022-SPPA-final.pdf.

“National Theatre’s First Live 4K Broadcast.” NEP Group. Accessed March 4, 2025. https://www.nepgroup.com/resources/national-theatres-first-like-4k-broadcast.

Nesta. “Digital Broadcast of Theatre/Learning from the Pilot Season: NT Live.” 2011. Accessed March 4, 2025. https://media.nesta.org.uk/documents/nt_live.pdf.

Nielsen. "Daily time spent with selected media in the United States in 1st quarter 2020, by age group (in minutes)." Chart. August 13, 2020. Statista. Accessed April 13, 2025. https://www-statista-com.cmu.idm.oclc.org/statistics/233386/average-daily-media-use-of-us-adult-population-by-medium/.

Phelan, Peggy “Preface: arresting performances of sexual and racial difference: toward a theory of performative film,” Women & Performance: A Journal of Feminist Theory, 1993, 6, 2:5–10.

Pierson, Alexandra. "What Streams May Come." American Theatre, August 19, 2024. https://www.americantheatre.org/2024/08/19/what-streams-may-come/.

Pierce, Jerald. "If You Live-Stream It, Will They Watch?" American Theatre, December 15, 2021. https://www.americantheatre.org/2021/12/15/if-you-live-stream-it-will-they-watch/.

Reason, Matthew. “Theatre Audiences and Perceptions of ‘Liveness’ in Performance.” Participations: Journal of Audience and Reception Studies 1, no. 2, May 2004. https://ray.yorksj.ac.uk/id/eprint/912/.

Reason, Matthew. “Young Audiences and Live Theatre, Part 2: Perceptions of Liveness in Performance.” Studies in Theatre & Performance 26 (3): 221–41, 2006. doi:10.1386/stap.26.3.221/1.

"Spirit of Radio." The Metropolitan Opera. Accessed March 26, 2025. https://www.metopera.org/discover/articles/spirit-of-radio/.

"The Met Announces Launch of New Streaming Platform, Making Live Simulcasts Available for Home Audiences." The Metropolitan Opera. Accessed April 10, 2025. https://www.metopera.org/about/press-releases/the-met-announces-launch-of-new-streaming-platform-making-live-simulcasts-available-for-home-audiences/#:~:text=The%20Live%20at%20Home%20season,Die%20Zauberfl%C3%B6te%20(June%203).

Wallace, Ian.“What Is Post-Internet Art? Understanding the Revolutionary New Art Movement.” Artspace, March 18, 2014. http://www.artspace.com/magazine/interviews_features/post_internet_art.

We Are Social, und DataReportal, und Meltwater. "Average daily media use in the United States in 3rd quarter of 2024, by medium (in hours.minutes)." Chart. February 25, 2025. Statista. Accessed April 13, 2025. https://www-statista-com.cmu.idm.oclc.org/statistics/1289938/daily-media-usage-us/.

Wooden, Isaiah Matthew. "Effective Dreaming in the Time of Zoom Theatre: Reflections on Directing the Lathe of Heaven." Theatre Topics 32, no. 3 (11, 2022): 127-137. doi:https://doi.org/10.1353/tt.2022.0026. https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/effective-dreaming-time-zoom-theatre-reflections/docview/2812054296/se-2.

Wyver, John. “In the Beginning: When We Are Married (BBC, 1938) 1.” Screen Plays, December 19, 2011. https://screenplaystv.wordpress.com/2011/09/22/in-the-beginning-when-we-are-married-bbc-1938-1/.

“10 Years On Screen | National Theatre Live, 2019.” YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=T94kV4W24RE.

"2021-22 Annual Report." National Theatre. Accessed April 10, 2025. https://images.nationaltheatre.org.uk/uploads/2023/01/NT_annual_review_national_theatre_2021-22.pdf#_gl=1*ra1wod*_gcl_au*MTQ2MjE1Njc5OC4xNzQxMTQxOTA5.