The power of the arts is undeniably transformational for individuals and communities. Public art specifically can enhance our outer world and allow anyone to view free, accessible art. This article examines murals as a specific form of public art to explore how their creation can generate lasting social, civic, and cultural impacts within the communities they inhabit. The following offers a historical perspective on the evolution of mural-based works and the impact of technological integration on public artists today.

Figure 1: Welcome to NoHo - North Hollywood mural, NoHo Community Volunteers, by Artist Susan Krieg, 2003. Photo by Jay Galvin

Murals as Assets, Preservation, and Advocacy

Public art, like all art, can be viewed as a political act. While the most common definitions frame it as an aesthetic enhancement to a shared physical space, its enduring and evolving role is as a vibrant medium for social dialogue, serving as both a tool for state vision and a powerful platform for citizen demonstration. By its nature—typically free and universally accessible—public art, and murals specifically, have the ability to democratize expression and serve as communicators across linguistic and class barriers.

This notion makes the study of murals critically important at this moment. They are not merely decorative; rather, they function as accessible, localized, and enduring assets for cultural preservation and community advocacy. Through vivid storytelling, murals preserve collective memory, make complex histories readily available to the public, and help forge distinctive community identities that can engage and unify residents while also acting as a visual form of resistance against gentrification, neglect, and systemic erasure. This political function becomes especially clear in the tension between state-sanctioned monuments and citizen-driven murals, demonstrating that the selection, placement, and perpetuation of public art are inherently political acts that continually engage with, challenge, or affirm dominant narratives.

History of Murals Globally: An Ancient, Universal Medium

The impulse to create and display art in shared, communal environments is an ancient, fundamental, and widespread human activity, one that has consistently served as a vital medium for recording social life and preserving cultural memory.

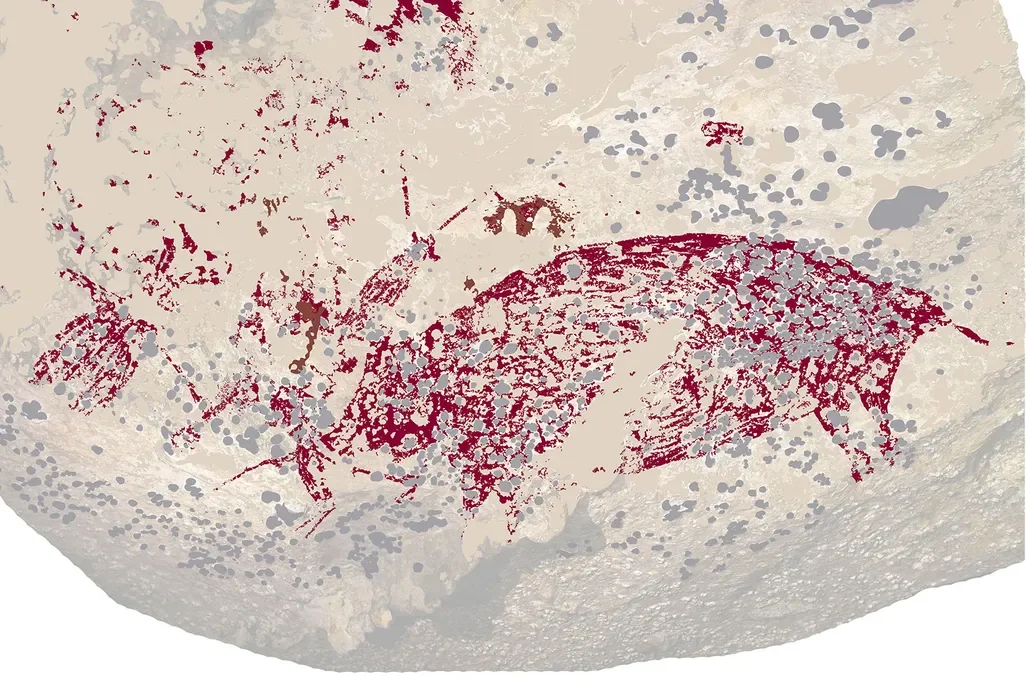

The earliest evidence of this practice predates written history, with the oldest known figurative painting discovered in the Leang Karampuang cave in Indonesia and dated to approximately 53,000 years ago. These findings fundamentally challenge the long-held assumption that the earliest forms of complex artistic thinking originated in Europe, revealing that such practices predate comparable European examples by millennia. This narrative composition depicts human-like figures interacting with a pig and is currently recognized as the earliest known surviving example of representational art and visual storytelling in the world.

Figure 2: Dated rock art panel at Leang Karampuang. Source: Smithsonian Magazine, Provided by Griffith University

Later, in the European Middle Ages, the function of public-facing art became a vehicle for institutional religious and political messaging. Medieval church murals served as essential pedagogical tools used by religious leaders to illustrate complex scripture and moral lessons for a largely illiterate populace. These visual narratives were primarily commissioned by wealthy donors or repentant parishioners as strategic acts of penance, ensuring that the decision-making power over the wall’s content remained a negotiation between ecclesiastical authority and those seeking to memorialize their own piety and social status.

Figure 3: Two angels playing nyckelharpa painted in the ceiling fresco of the church of Tolfa, commune of Tierp, Uppland, Sweden. Unknown painter second part of 15th century (1503). Source, Wikimedia

This demonstrates a persistent tension between aesthetic, historical, and religious value, where state agencies eventually appropriated and re-contextualized religious art as secular markers of national identity, reinforcing the state's power to define culture. While the ancient Indonesian cave paintings represent the decentralized origins of this impulse and prove that creating art on communal surfaces is a universal practice, the shift toward institutional control highlights a long-standing but evolving drive to use public display for storytelling and the transmission of knowledge.

The Evolution of American Muralism and Urban Resistance

The mural form was revitalized across the Americas during the 20th century as a potent political and social tool. While both the Mexican government and the United States government utilized muralism to employ artists during times of crisis, their underlying intentions and the long-term outcomes of their support differed significantly.

Emerging in the immediate wake of the Mexican Revolution (1910–1920), the Mexican Muralism movement was a strategic, state-backed project designed to unify a fractured nation. The post-revolutionary government commissioned artists like Diego Rivera, José Clemente Orozco, and David Alfaro Siqueiros to create a new national identity.

Figure 4: The Trench (La Trinchera), 1926, fresco, Courtyard, National Preparatory School, José Clemente Orozco, 1926. Source: Mexicanmuralism

Their intent was fundamentally ideological and pedagogical, as they utilized social realism to celebrate Indigenous history and labor while creating a visual literacy for a population that was largely excluded from traditional academic circles.

The Mexican state viewed murals as a permanent tool for nation-building, and the movement received long-term institutional support that allowed it to become a global standard for political art. Today, this legacy persists in the work of contemporary artists like Seher One, a muralist and graphic stylist, and Paola Delfín, a monochromatic muralist and visual artist, who continue to use the public wall to negotiate Mexican identity in the 21st century.

Murals became an effective medium for strengthening cultural identity and communicating with citizens regardless of literacy levels. Their success also highlights the complex relationship between government involvement in public art and the importance of empowering artists with cultural ties, clear vision, and creative freedom.

In contrast, the "new" American Muralism born out of the Great Depression was primarily driven by the economic revitalization goals of the New Deal. Between 1935 and 1943, the Federal Art Project (FAP) of the Works Progress Administration (WPA) commissioned over 2,500 murals. While influenced by the aesthetic power of the Mexican movement, the U.S. government’s intent was distinctly focused on economic relief and morale-boosting for unemployed artists rather than radical ideological revolution.

Figure 5: Spring in Georgia by Andree Ruellan, 1942, Courtesy of U.S. General Services Administration, Public Building Service, Fine Arts Collection. Source: New Georgia Encyclopedia

As a result, mural depictions varied widely by region and local public history, reflecting each community’s relationship to its past. Although the U.S. government did not officially dictate the style or content of the murals it sponsored, it strongly encouraged artists to create work with the public in mind. In particular, artists commissioned by the Treasury were expected to spend time within the community and solicit input on themes, leading to murals that expressed distinct regional narratives shaped by local history, values, and collective memory.

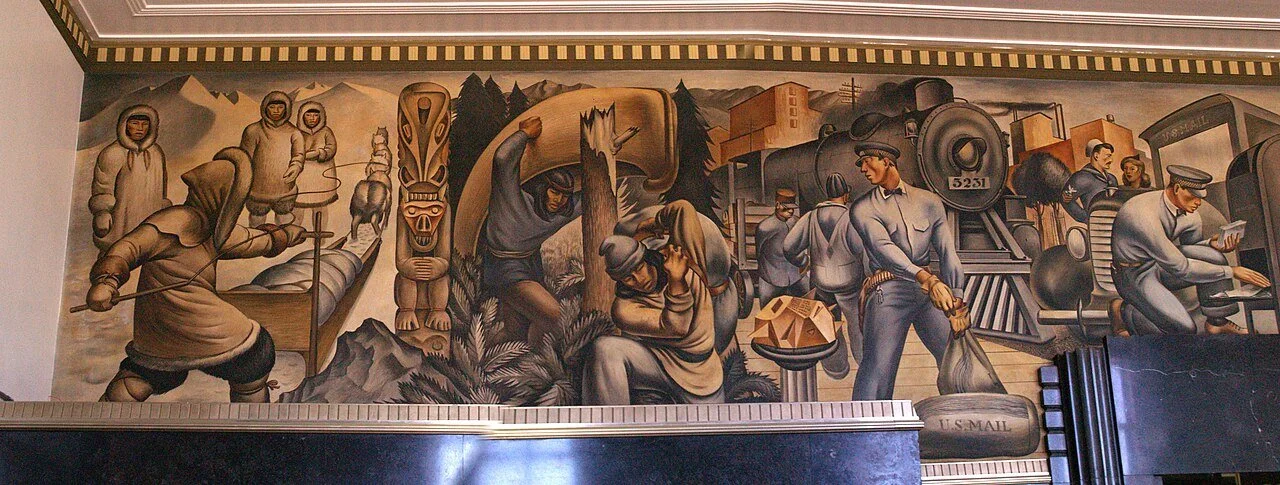

Figure 6: Mail Transportation, 1938, San Pedro, CA., Post Office WPA Mural left side, Fletcher Martin

Crucially, the government’s push for the arts opened doors for artists of color, offering early professional opportunities that helped launch the careers of figures such as Jacob Lawrence, Aaron Douglas, and Samuel Joseph Brown Jr.

President Roosevelt’s belief in the arts as both an economic driver and a morale booster affirmed the value of creative labor within public life. Yet, given the broader context of systemic inequity, it remains necessary to question the extent to which these programs genuinely intended to support diverse artistic expression or if they primarily served state interests in shaping a homogeneous public narrative.

The divergent outcomes of these movements highlight a core tension: the Mexican movement succeeded in creating a permanent, radical national aesthetic, whereas the U.S. movement created a professional infrastructure that marginalized artists eventually reclaimed.

From Sanctioned Art to Grassroots Demonstration

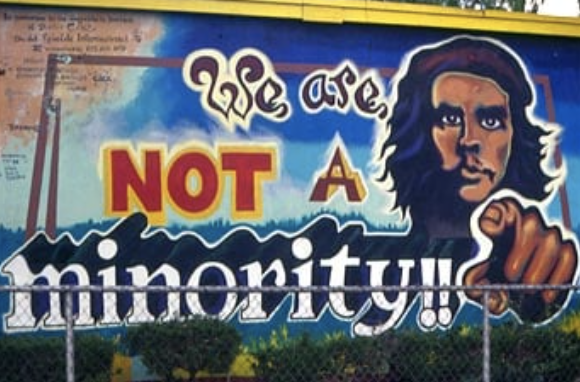

Figure 7: We Are Not A Minority by Congresso de Artistas, 1978, in Los Angeles, California. Image courtesy of Chicano Art. Source: THSA

In the decades following the WPA and Mexican Muralism Movement, particularly during the Civil Rights and Chicano movements of the 1960s and 70s, the public walls were reclaimed by marginalized communities. Murals transformed into essential instruments of protest and empowerment, utilizing public space not for government endorsement but for highlighting civil struggles, celebrating autonomous cultural pride, and documenting social injustice. The commissioning body shifted from the state to the community itself, marking a distinct return to the decentralized, resistive function of the ancient mural.

Figure 8: The Wall of Respect, a public art project in Chicago, 1967. Photograph: Robert Abbott Sengstacke/Getty Images. Source: Guardian

The Street Art Revolution

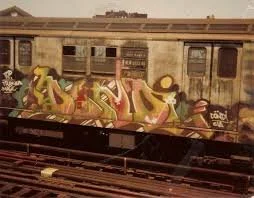

The most radical modern evolution of public art began with graffiti, which emerged from marginalized, largely Black and Latinx urban communities in New York and Philadelphia in the 1960s and 70s. Young artists, known as "writers," used highly stylized lettering and tags to assert identity and claim visibility in an often ostracized environment, most famously on the subway cars. This Hip-Hop culture cornerstone was initially criminalized as vandalism, but possessed a raw political energy that caught the attention of the art world.

The movement directly gave rise to modern street art, a broader category encompassing murals, stencils, and wheatpaste that engaged with social themes. At this time, graffiti artists also unionized for the first time, pushing back against discrimination of marginalized artists and banding together to disperse equitable opportunities in the U.S. and abroad. However, wealthy arts began to selectively elevate only certain graffiti artists into curated, profit-driven spaces, a move that fractured unions and fueled the infighting and resentment that ultimately eroded their collective power.

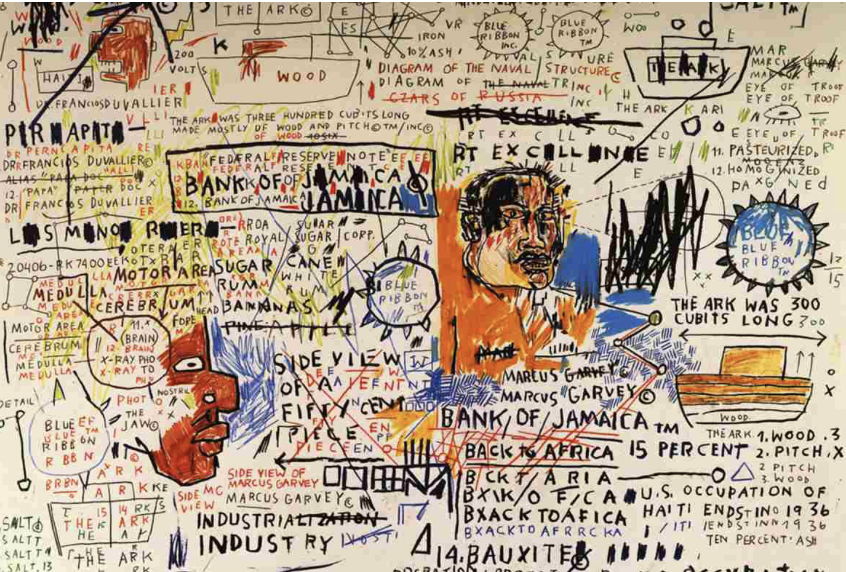

Pioneers like Jean-Michel Basquiat and Keith Haring successfully transitioned the aesthetics and energy of this urban expression into galleries, blurring the lines between transgressive street expression and high art, and cementing the public, political, and cultural power of the mural in the 21st century.

Figure 10: 50 Cent Piece, Jean-Michel Basquiat, 1983-83. Source: DBFA

Modern Challenges: Censorship and Institutional Control

The tension between artistic expression and institutional control is can be clearly demonstrated through censorship, which forces a confrontation regarding who holds ultimate authority over public visual space: the artist, the commissioning body, or the community.

A notable example of this institutional overriding of artistic intent occurred in 2010 when the Museum of Contemporary Art (MOCA) in Los Angeles commissioned Italian street artist BLU. BLU used the exterior wall of the museum’s Geffen Contemporary building to critique the over-militarization of U.S. society, depicting coffins draped in dollar bills instead of American flags. Before the exhibition opened, MOCA Director at the time, Jeffrey Deitch, ordered the mural to be immediately whitewashed, citing the imagery's potential to offend a nearby veterans' center.

Figure 11: Workmen erase the offending images. Photograph: Casey Caplowe. Source: The Guardian

This incident highlights the conflict between private commission and public platform. While MOCA had the legal right to control its property, the swift censorship of political art in a highly visible public setting sparked debate over whether private ownership supersedes the public's opinion and right to engaging, challenging dialogue. Similarly, murals funded by government grants or community groups face political review, often dictated by the perceived funding source and the community's expectation of the art’s message. Censorship proves that even when murals achieve visibility, they remain inherently subject to the political will and authority of the entity that controls the wall.

Technological Integration

Contemporary muralists are increasingly utilizing advanced digital tools and techniques, fundamentally changing the entire design and execution process. This integration transforms the mural from a static, two-dimensional painting into a more precise, efficient, and interactive medium.

In the early stages of conceptualizing and creating mock-ups, artists now employ digital prototyping and precision techniques for a more accurate conversion from concept to wall. Using software like Procreate or Photoshop, artists create detailed, to-scale prototypes. This digital stage helps enable the successful visualization of highly complex compositions and color palettes before any paint is applied.

The physical transfer of the design onto the wall is similarly optimized through Spatial Computing tools. For massive works, high-resolution projectors or Augmented Reality (AR) glasses are utilized. Functioning as a "digital stencil," this technology guides the artist's freehand work, allowing for the rapid and precise transfer of complex designs onto vast walls.

Another growing application of this technology is the creation of Interactive Murals, which redefine the artwork's relationship with its audience. Artists are now using AR to layer digital content—such as animations, sound, and interactive elements—over the finished physical mural. The integration of AR transforms the mural into a dynamic, interactive experience that deepens audience engagement and effectively broadens the artwork's communication capacity within the public sphere.

These advancements underscore that technology is not replacing the artist but acting as an amplifier, making murals more precise, efficient to execute, and capable of dynamic, multi-sensory storytelling as a potent tool for 21st-century community advocacy.

The Power of the Public Wall

Throughout history, murals have transitioned from decentralized universal expressions to powerful political tools used by both states to reinforce national identity and marginalized communities to assert resistance against systemic erasure. Today, this battle for legitimacy is further evolving through technological integration, as artists utilize digital prototyping and augmented reality to bypass traditional censorship and create interactive, multi-sensory advocacy tools for the 21st century.

Figure 12: Black Lives Matter and Justice for Breonna Taylor mural drawn on College Avenue in Berkeley, California. Artist unknown. Source: Harvard Political Review.

-

Aubert, Maxime, Rustan Lebe, Adhi Agus Oktaviana, Muhammad Tang, Basran Burhan, Hamrullah, Andi Jusdi, et al. “Earliest Hunting Scene in Prehistoric Art.” Nature (London) 576, no. 7787 (2019): 442–45. doi:10.1038/s41586-019-1806-y.

Boggs, Jada. "Mexican Muralism—The Origins and Revolution of Street Art." Copyright Alliance Blog, September 20, 2022. https://copyrightalliance.org/mexican-muralism/

Choi, Caroline. "Street Art Activism: What White People Call Vandalism." Harvard Political Review, October 21, 2020.https://harvardpolitics.com/street-art-activism/

Damage, Danny. “1980s Graffiti: How the Artform Went From City Streets to Gallery Spaces.” Sound of Life, May 7, 2024.https://www.soundoflife.com/blogs/design/80s-graffiti.

Dawson, Natalie. “The History of Murals in the United States.” Book An Artist, March 2, 2023.https://bookanartist.co/blog/the-history-of-murals-in-the-united-states/.

Glaister, Dan. “Los Angeles Museum Commissions Mural — Then Obliterates It.” The Guardian, December 19, 2010.https://www.theguardian.com/world/2010/dec/19/los-angeles-museum-obliterates-mural

Glueck, Grace. “Artists Vote for Union and a Big Demonstration.” The New York Times, September 23, 1970.https://www.nytimes.com/1970/09/23/archives/artists-vote-for-union-and-a-big-demonstration-meeting-here-of-300.html.

Klacsmann, Karen Towers. “Andree Ruellan (1905–2006).” New Georgia Encyclopedia, March 28, 2008; last modified August 14, 2013.https://www.georgiaencyclopedia.org/articles/arts-culture/andree-ruellan-1905-2006/.

Lagunas, Zaida. “Mexican Artists’ Political Murals.” The Collector, August 27, 2024. https://www.thecollector.com/mexican-artists-political-murals/

Liepe, Lena.“A Case for the Middle Ages: The Public Display of Medieval Church Art in Sweden 1847–1943, reviewed by Benjamin Zweig.” The Medieval Review, November 11, 2019. Indiana University ScholarWorks. https://scholarworks.iu.edu/journals/index.php/tmr/article/view/28931

Martinovic, Jelena. “A History of Protest Art Through Examples — From Ai Weiwei to Banksy.” Artsper Magazine, June 30, 2025. https://blog.artsper.com/en/a-closer-look/art-movements-en/protest-art/

Moore, Peter. “Most Americans Say That Graffiti Can Be Art, but Opinion Is Divided on Whether or Not It Is Vandalism.” YouGov, April 29, 2014.https://today.yougov.com/society/articles/9250-graffiti

Oktaviana, A. A., Renaud Joannes-Boyau, Budianto Hakim, Basran Burhan, Ratno Sardi, Shinatria Adhityatama, Hamrullah, Iwan Sumantri, et al. 2024. “Narrative Cave Art in Indonesia by 51,200 Years Ago.” Nature 631 (8022): 814–818. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-024-07541-7.

Orozco, José Clemente. 1940. “Dive Bomber and Tank.” Fresco, six panels. Museum of Modern Art (MoMA). Accessed January 28, 2026.https://www.moma.org/collection/works/80681

Panasonic Connect North America. “Public Art in Motion: Bringing the Magic Mural to Life with Projection Mapping.”Panasonic Connect, January 2, 2025.https://connect.na.panasonic.com/blog/av/visual/public-art-in-motion-bringing-the-magic-mural-to-life-with-projection-mapping.

James, S. Christopher. “The WPA and Its Lasting Impact on Art and Design in the United States.” Union Design Company. August 31, 2025. https://uniondesigncompany.com/the-wpa-and-its-lasting-impact-on-art-and-design-in-the-united-states/.

Swedish History Museum, “Swedish Medieval Church Murals,” Historiska: History Hub, November 10, 2025, https://historiska.se/en/explore-history/history-hub/medieval-church-wall-paintings/.

UCSC News. “The Writing on the Wall: Exploring the Cultural Value of Graffiti and Street Art.” September 2021. https://news.ucsc.edu/2021/09/graffiti-street-art.

Wikimedia Commons contributors, “NYCS R21 exterior tagged.jpg”, Wikimedia Commons, accessed November 25, 2025. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:NYCS_tagged_IRT_train.jpg.

"Works Progress Administration(WPA) Murals ." St. James Encyclopedia of Popular Culture. Encyclopedia.com. Accessed January 28, 2026). https://www.encyclopedia.com/media/encyclopedias-almanacs-transcripts-and-maps/works-progress-administrationwpa-murals

Young, Tamlyn, and Mark T. Marshall. 2023. "An Investigation of the Use of Augmented Reality in Public Art" Multimodal Technologies and Interaction 7, no. 9: 89. https://doi.org/10.3390/mti7090089