By: Isaiah Aaron Jones

The training background of an actor may encompass one specific pedagogical approach or an amalgamation of many. One of the most infamous is method acting, or “The Method,” introduced in the United States by Lee Strasberg and Elia Kazan in the 1930s. Though most prominent in film acting, many stage performers have adopted method acting as their modus operandi when constructing a character. To utilize this technique, actors “[feel] the character’s emotions rather than acting them, which they do through exploring their own experiences and feelings;” in other words, method actors immerse themselves fully into the character. (BBC Maestro 2025)

There are many critics of The Method, citing the possibility of actors getting so immersed in their character’s psyche that it leads to psychological harm and a struggle in separating fiction from reality. Stella Adler, another storied pioneer in acting education, cultivated her own technique that stemmed from method acting technique, where “full immersion in the lives of characters demanded intensive research and imagination,” and focus beyond an actor’s own experiences and into the “given circumstances” of the character resulted in more grounded work. (Kisner 2022)

Figure 1: Actor and therapist caricature illustration. Source: Al Hirschfeld Foundation

Though there are differences between Strasburg/Kazan and Adler’s viewpoints, one action serves as a through line in their teaching: immersion. Consider a new outlook on acting training — one where institutionally renowned and revered traditional methods are merged with the ever-changing technological landscape of the 21st century.

Enter XR stage right.

XR, or extended reality, is an immersive technology that includes virtual reality (VR), augmented reality (AR), and mixed reality (MR). In a nutshell, virtual reality is a setting in which the “world” is completely virtual, with little to no presence of reality as we know it; augmented reality overlays virtual elements within real-life environments, and mixed reality blends the two, where users still have an attachment to the real world but with additional immersive capabilities. (Vection Technologies)

These types of technologies have been in the arts for decades. However, their usage in the training of actors is still relatively nascent. While this introduces a world of possibilities for both practitioner and profession, it also opens a Pandora’s box of ethical, legal, and social concerns.

Augmented Reality (AR)

To reiterate, AR superimposes virtual elements onto real-world environments. As Hayder Jaafar Aldaghlawy, professor of theatre arts at the University of Basrah, points out, “Integrating [AR] into actor training can generate immersive experiences crucial for enhancing skills” and “by overlaying virtual information in the real world, [creates] a highly interactive and engaging setting.” (Aldaghlawy 2024, 133) The standard approach to training, Aldaghlawy stresses, lacks fully immersive experiences and immediate feedback. With AR, actors are able to have live interactions with virtual props, arrange realistic simulations that mirror performance environments, interact with historic events that may inform their character development, and replicate situations in a safe environment (as opposed to method acting, where the actor is actually exposing themselves to potentially harmful conditions).

Let us take a step back.

Before introducing AR into pedagogy, a needs assessment must be conducted in order to consider the circumstantial practicality of the technology. This includes:

Creating clear learning objectives

Finding suitable technology

Ensuring actors are ready and have an understanding of this method

Designing simulations that can be easily adjusted

The latter is crucial, as it allows the employment of a personalized approach for actors, i.e. adapting to their characters’ circumstances (if they’re a surgeon, having simulations inside an operating room) and their personal learning preferences as students.

This system utilizes wearable technology that records performances and leads to instantaneous feedback via visual signals. With digital features overlaid onto the real world, this works by “enabl[ing] the gathering and analysis of data to monitor the advancement of individuals and discover areas that want enhancement.” (Aldaghlawy 2024, 137) Furthermore, “The feedback process strengthens desirable behaviors and rectifies mistakes, improving the proficiency of the individuals involved.” (Aldaghlawy 2024, 137)

The customization capabilities of this technology merged with data analytics and machine learning algorithms assessing actors’ performances allow individualized feedback that focuses on their areas of most need, which leads to greater emotional insight for an actor and their character.

Figure 2: Actors interacting with an augmented reality dragon onstage. Source: Glitch Studios

The construction of this system enlists the techniques of “transfer mechanisms” that are strategically implemented to enhance the four-component of instructional design (4C/ID) model: (The Grove Center)

Tasks

Supportive Information

Procedural Information

Part-Task Practice

This academic approach to technology-infused acting training fosters a highly educational environment where theory and practice reach an equilibrium.

AR in acting training hosts a multitude of possibilities, not only for the actors, but for the institutions implementing this technology. From an economic perspective, AR decreases the “duration and expenses of training while enabling flexible learning and safe experimentation.” (Aldaghlawy 2024, 135) For actors, through the immersive element of AR, they are able to fully engage in situations that they may not otherwise be able to access, allowing them to build their characters in new ways. As a result, it allows actors to grow, increasing their emotional aptitude, creativity, and adaptability in varying environments.

In addition, it provides a greater foundation for dramaturgical work in training for actors. In AR, users would be able to “arrange virtual visits to historical locations and museums,” opening the door for a greater understanding of what a character may need, or need to know, in a given situation or circumstance à la Stella Adler. (Aldaghlawy 2024, 135)

While there are many potential benefits of AR in acting training, there are obstacles as well. Although the simulation of being in hazardous situations in AR is arguably the “safer” approach compared to the Method, being in simulated environments still has the potential to be detrimental to an actor’s mental health. In that same vein, excessive usage of the technology can lead to social isolation and a reliance on virtual enhancements. There is also the issue of equitable availability of the equipment and proper training for the usage of the technology for educators on how to introduce it into their curriculum. Ironically, this may lead to job displacement for educators and dramaturgs, as institutions may turn to XR in a more extensive way as opposed to as a supplement.

Incorporating sociopolitical factors within the technology is also a major element when considering using AR. To facilitate this type of learning most effectively, practitioners must build simulations that accurately reflect the society and political environment needed for specific characters, which can certainly stir adverse emotions and lead to negative reactions (regarding race, gender, sexuality, etc.). Finally, managing user data alone may outweigh the advantages of the technology, as that is a large undertaking from a legal and ethical standpoint.

Overall, the tailored learning opportunities that AR in acting training affords can lead to a liberation for actors where traditional techniques alone may not have been as effective, or safe, for them. Integrating this technology into traditional methods reinvigorates the training landscape, fostering a more robust and collaborative practice. However, it is vital to understand the many issues that this may pose and assess the needs of actors and educators first and foremost in order to promote a healthy and productive learning experience.

Mixed Reality (MR)

In life, humans interact with their given environmental constraints on a daily basis, for example, a person performs an action and their environment/surroundings respond accordingly. Additionally, constraints inform relations, be they human-to-human or human-to-inanimate objects. In acting training, constraints are crucial, as they help create and form an understanding of the world and desires of characters. The literal constraints for actors, like the stage, props, and fellow cast members, are also important when doing this work.

Manipulating certain constraints in the real world proves to be quite challenging in many instances. However, in mixed reality, it is a much easier, and smoother, process.

Three students from Ghent University in Belgium studied the manipulation of constraints in altered reality technology for theatre training, primarily by aligning it with the practices of Odin Teatret in Oslo, Norway.

Figure 3: Odin Teatret performers in masked ensemble. Source: Routledge Performance Archive

Odin Teatret, created in 1964, is a theatre troupe and a laboratory of sorts where “actors and dancers meet with scholars to compare and scrutinize the technical foundations of scenic presence.” (Odin Teatret) They also strive to explore and understand the “psychophysical strategies [of the body] to enhance actor’s presence.” (Odin Teatret) The Ghent students hypothesized that by incorporating external constraints within mixed reality, they would “invite people to act differently” and “to get to know other forms of understanding presence and imagination, expanding the notion of pre-expressivity through virtual archives.” (Marouda et al. 2023, 55)

Correspondingly, the environments they formed in mixed reality had several constraints, like the usage of sound, or lack thereof, which created “a ground of defiance of physical rules and experimentation” and encouraged “constant interactions between a user’s bodily actions and corresponding (re)actions of the XR multimodal environment.” (Marouda et al. 2023, 60) What makes this experiment mixed reality is its usage of a virtual space with elements that users can interact with. This, in theory, would give actors the “permission” to play more in their training all the while expanding their adaptability.

In this experiment, where Oculus headsets were primarily used, they found that the use of constraint-based interactive VR environments “carried kinesthetic information that can change the way participants perform [actions].” (Marouda et al. 2023, 69) Users were tasked to perform a set of actions with varying degrees of energy that emulate six states of water (fog, bubbles, amazon river, little creek, iceberg, and tempest). Their goal was to “enhance the experience of each related state with the aid of interactive visual effects and soundscapes and as a result, impact the quality of [action].” (Marouda et al. 2023, 61) This not only pushed the users to experiment more and take risks, but it also built a world for them to freely expand their imagination, which will, hopefully, then aid them on the stage.

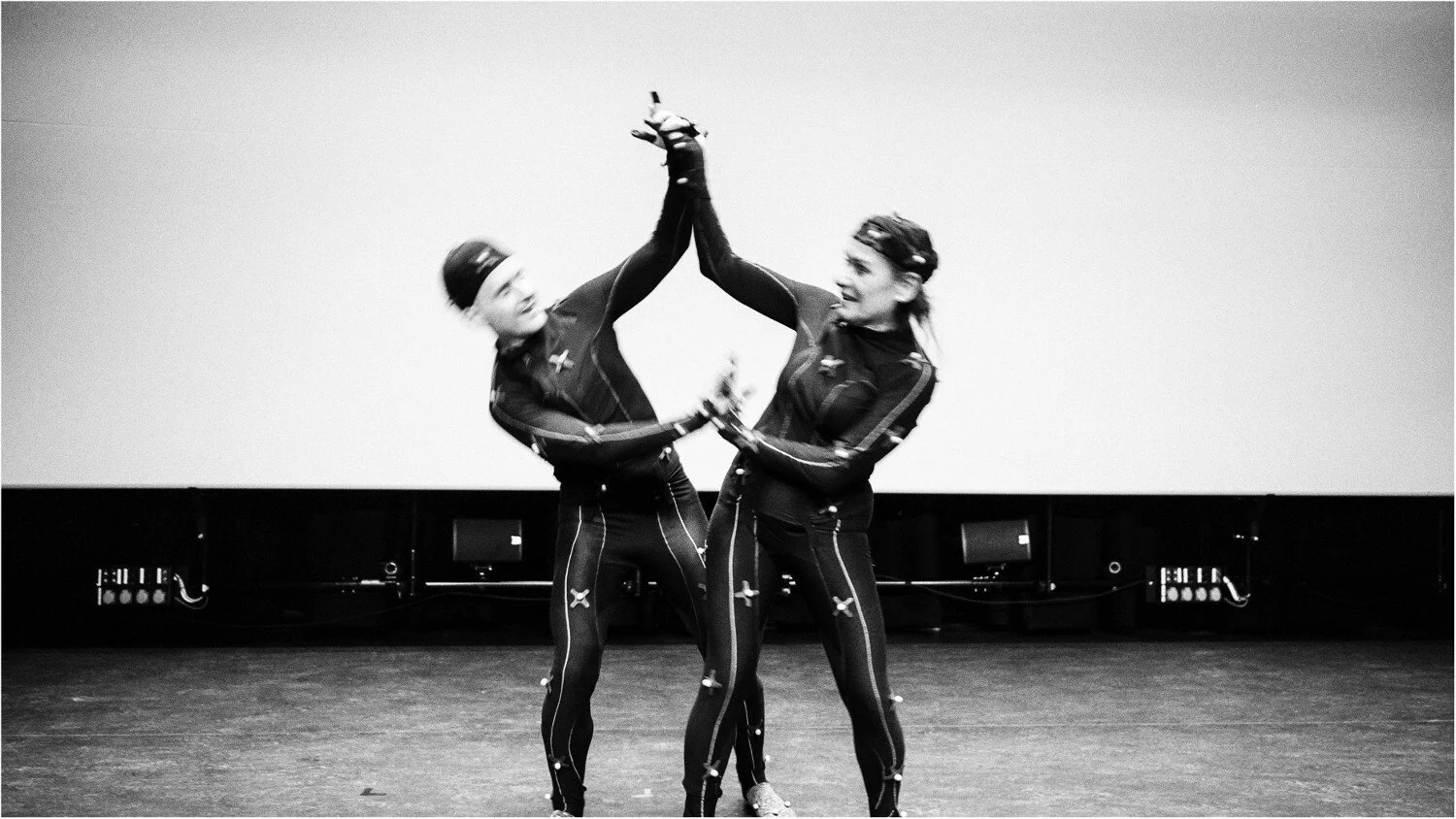

Figure 4: Motion-capture actors in rehearsal. Source: Bruno Freire

In essence, this revealed how visual and sound effects, specifically in immersive settings, affect movement and creativity.

Much like the AR experiment detailed earlier, there are still negative factors to take into account, specifically in the effects of overuse, job displacement, and data privacy management.

Virtual Reality (VR)

The Juilliard School, known for its rigorous conservatory training, continues to be on the cutting edge of performing arts education. In a collaboration with the Creative Associates group and the Builders Association, they have joined in tapping the potential of merging VR and acting training.

The Builders Association, an award-winning multimedia performance company based in New York, has “created a significant body of work at the intersection of media and performance” since its inception in 1994. (The Juilliard School) With The Juilliard School, they worked with 12 Drama Division students in a weeklong workshop exploring virtual reality on the stage and enlisted the help of a team of technicians and Oculus headsets. What the students faced was “how to approach theater on a proscenium stage through the lens of technology.” (Cruz Cuberos 2023)

VR and theatre are quite oxymoronic at first glance. Theatre, by nature, is a highly collaborative and community-driven practice that fully incorporates the body in a shared environment. VR, in its typical usage, can usually be antithetical to that, where the full usage of the body in a communal space is not the overarching goal.

Primarily, the Juilliard students and the Builders Association wanted to “investigate how virtual reality can coexist within a ‘live’ theatre space in a compelling way.” (Cruz Cuberos 2023)

They staged an adapted scene from Edmond Rostand’s Cyrano de Bergerac, where Cyrano comes in (unrevealed) to speak in place of a man who is trying to seduce the woman Cyrano loves. Since “layers and masking of identity [are] so central to the virtual reality space,” this scene worked beautifully for this experiment. (Cruz Cuberos 2023)

To bring VR to the stage properly, there were two screens upstage left and upstage right that projected what the actors were seeing in their headsets in real time. The actors used avatars and remotes to navigate through the virtual environment. Typically in VR, only one person manipulates a singular avatar. However, the Builders Association wanted to upend that notion by giving the controllers to two different actors while another actor wore the headset. This challenged them not only individually, but also in their ability to collaborate effectively.

“When the virtual avatar was being controlled by three people instead of one, it created a piece that was compelling to watch on stage and on screen, as it resulted in the avatar and actors working in synchronized, dancelike movements.” (Cruz Cuberos 2023)

While the principal goal was to gain a deeper understanding of how VR and live theatre can work in tandem, a major finding from this experience for the actors was how they were not only able to collaborate with fellow actors, but with the technicians in the staging of the piece. With the Builders Association, they were able to be a part of the production process, particularly in the sound and video design.

This exemplifies how implementing XR technology into acting training not only forms a more vigorous grasp on practical concepts, but allows actors to become more well-rounded artistic individuals who have a better understanding of production.

Higher Education & XR at Large: Legal, Ethical, & Social Concerns

Though the topic at hand is the direct linkage between XR in acting training, it is crucial to note XR's adoption in higher education as a whole. The general argument in favor of this is for students to “develop and advance communication, public speaking, and interviewing skills by practicing in virtual simulations.” (Georgieva et al. 2024) With its popularity expedited by the pandemic, institutions cite this technology with the ability to nurture creativity and imagination due to its unique levels of engagement and interaction. When looking at XR at a macro level in terms of higher education, however, one can’t help but notice the clear legal, ethical, and social concerns that are present.

FERPA, or the Federal Education Rights and Privacy Act, is a federal law that “affords parents the right to have access to their children’s education records, the right to seek to have the records amended, and the right to have some control over the disclosure of personal identifiable information from the education records.” (U.S. Dept. of Education) When the student turns 18, or enters a postsecondary institution even before they turn 18, those rights are then turned over to the student. Something that is included in this protection is a student’s biometric data, of which many XR devices collect. This begs the question, “When are FERPA consent and waiver forms needed… and what data security obligations are created from the collection of the data.” (Georgieva et al. 2024)

The manufacturer of the XR headsets, the app developers, and the managing institutions of the devices can, in some way, collect data from this technology. In order for these devices to be used ethically in the classroom, there needs to be a clear understanding of how the data will be handled, or destroyed, via informed consent.

Figure 5: VR learning simulation. Source: Oksana Klymenko

When considering XR in acting training, a large portion of what is being tracked is movement, eye tracking, gaze, and potentially heart rate. Legally, this data also falls under the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) and must be taken into consideration in the same ways that FERPA-related data is.

Socially and ethically, there are other inherent issues with XR, specifically in regard to digital Blackface.

Digital Blackface, which is “a practice where White people co-opt online expressions of Black imagery, slang, catchphrases, or culture to convey comic relief or express emotions,” is already a major issue on social media platforms. (Blake 2023) If a student chooses “avatar features that may not be representative of their appearance, ethnicity, and culture in the real world” in the spirit of “exploring a character,” where do institutions draw the line? (Georgieva et al. 2024) Relatedly, developers must ensure that there is a wide range of options available when creating an avatar’s appearance in accordance with Title VI of the Civil Rights Act.

Finally, with Title IX, what systems will be in place for instances of virtual sexual harassment? For actors, will there be a virtual intimacy coordinator?

While this technology is certainly not new, the infrastructure is scores away from being solid, particularly when trying to incorporate it into higher education. In addition, nonprofit arts institutions with educational offerings may see the benefits of adopting this technology as well. For arts managers, it is vital to consider these legal and ethical concerns and have clear communication with the board, staff, and artists regarding usage and how XR training aligns with the overall mission of the organization. If they didn’t want to include this technology in their curriculum but still wanted to use it in some capacity, this would be a fantastic opportunity for community engagement. Having a few Oculus goggles with production-specific simulations available for community members or donors would be a great way to connect audiences with the work of the organization. For example, if you are producing Hairspray, you could have an XR simulation of Mr. Pinky’s Hefty Hideaway where users can virtually get their hair done and pick out an outfit.

More research and policy-driven discussions must be facilitated in order to reach a clearer mutual understanding within the arts and education sectors for the usage of this technology.

Path Forward

There are a plethora of ways to approach acting, and many actors undertake a multitude of them in their careers. When asked about what is missing in current theatre training, Dr. Pil Hansen, a Canadian dramaturg and professor, stated, “Many current training methods tend to teach different aspects of the process separately, and that can put up barriers between those aspects.” (Lewis and Bartley 2022) The fusion of XR and acting training allows budding practitioners, as well as seasoned professionals, to approach acting in a new, multidisciplinary way that challenges them as holistic artists.

However, caution must still be used just like when implementing the traditional methods of training. While method acting may be harmful for some, so too may XR, where young actors may be exposed to “potential trauma in their learning environments” virtually. (Lewis and Bartley 2022) Moreover, when students graduate and transition into the real world, they generally lose access to the technologies they’ve grown accustomed to using in their classes.

If educators aren’t careful, they may be sending actors into the world with a crutch as opposed to the intended leg up on the competition.

Extended reality offers many benefits that can aid actors in growth, creativity, and world-building for their characters. Nevertheless, having a thoughtful understanding and clear pedagogical approach when using XR is the starting point in acting training, and further policies around this technology are what will create a healthy framework for all artists, students, and educators alike.

-

Aldaghlawy, Hayder Jaafar. 2024. “A Proposed System for Using Augmented Reality Technology in Actor Training.” Basrah Arts Journal 28: 133–42. https://bjfa.uobasrah.edu.iq/index.php/Arts/article/view/286.

BBC Maestro. n.d. “What Is Method Acting?” https://www.bbcmaestro.com/blog/what-is-method-acting.

Blake, John. 2023. “Analysis: What’s ‘Digital Blackface?’ and Why Is It Wrong When White People Use It?” CNN, March 26.

https://www.cnn.com/2023/03/26/us/digital-blackface-social-media-explainer-blake-cec.Cruz Cuberos, Kassandra Norymar. 2023. “Acting in Virtual Reality at the Juilliard School.” Juilliard Journal, March 17.

https://www.juilliard.edu/news/162056/acting-virtual-reality.Georgieva, Maya, Jeremy Nelson, Ricky LaFosse, and Didier Contis. 2024. “XR in Higher Education: Adoption, Considerations, and Recommendations.” Educause Review, January 10.

https://er.educause.edu/articles/2024/1/xr-in-higher-education-adoption-considerations-and-recommendations.Kisner, Jordan. 2022. “The Madness of Method Acting.” The Atlantic, October 31.

https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2022/03/the-method-acting-isaac-butler-review/621310/.Lewis, William W., and Sean Bartley. 2023. Experiential Theatres: Praxis-Based Approaches to Training 21st Century Theatre Artists. New York: Routledge.

Marouda, Ioulia, Adriana La Selva, and Pieter-Jan Maes. 2023. “From Capture to Texture: Affective Environments for Theatre Training in Virtual Reality.” Theatre and Performance Design 9 (1–2): 52–73.

https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/23322551.2023.2218185.Odin Teatret. n.d. “About.” https://odinteatret.org/index.php/odin-teatret/.

The Grove Center. n.d. “4CID Framework.” Pennsylvania State University.

https://grovecenter.science.psu.edu/technology/instructional-design/4CID-framework.The Juilliard School. n.d. “The Builders Association.”

https://www.juilliard.edu/stage-beyond/creative-enterprise/creative-associates/builders-association.U.S. Department of Education. n.d. “What Is FERPA?”

https://studentprivacy.ed.gov/faq/what-ferpa.Vection Technologies. n.d. “What Is Extended Reality?”

https://vection-technologies.com/support/technology/what-is-extended-reality/.