By: Kyla Gardner

Did you know that some of the most visually striking scenes in recent cinema and television productions, like The Mandalorian and 1899 were filmed, not on remote, exotic locations or massive, sprawling sets, but were created inside towering LED walls? This recent technique, known as virtual production (VP), has transformed the way stories are told on screen. Instead of relying on green screen shooting at locations, waiting for months of post-production to bring digital worlds to life, film and production crews can now see immersive environments projected around them in real time.

For audiences, the result is seamless; most never realize that the sweeping desert landscapes or futuristic starships they see were generated on a soundstage. For the industry, however, VP represents a seismic shift, raising questions about cost savings, accessibility, and most importantly: what it means for the people who make the magic happen. This article will explore what virtual production is and how it reshapes creative labor, and what opportunities and challenges it presents for the future of the arts and entertainment industries.

What is VirtuAl Production?

Virtual productions (VP) is a filmmaking method that combines computer-generated imagery (CGI), augmented reality (AR), and motion capture to create virtual sets that emulate realistic environments within Volumes (the digital spaces) (DeGuzman, 2023). VP allows filmmakers to combine real-time rendering and camera tracking with physical sets, displayed on large LED screens that project high-resolution environments.

Figure 1: Traditional vs. Virtual Film Production Workflow. Source: Unreal Engine

VP is not a single technology but a workflow that combines real-time rendering, camera tracking, and massive LED scenes to merge digital and physical production. Creative teams can make decisions faster, make on-set adjustments to the rendered environment, and capture high-quality visuals (Seymour 2020; DeGuzman, 2023). Incorporating these technologies into the production process transforms the way stories are created and alters the roles required for these productions. This shift raises critical questions and potential concerns for these positions; set designers, location managers, and visual effects teams are amongst the few whose responsibilities are being redefined in a VP-driven workflow.

Workflow Shifts Across Departments

The rise of virtual production is not just a technological upgrade; it is a reconfiguration of creative workflows. “Traditional” film production roles, which normally operate sequentially, are now being worked on simultaneously. With VP, these roles foster a more collaborative environment and require a comprehensive understanding of both physical and digital spaces.

For set designers, their work focuses on physically building out the setting of the production to provide actors with a tangible space to work within. In virtual production, however, much of this work is replaced by 3D designers and artists to develop digital assets that appear on LED walls. For the production of The Mandalorian, for example, designers created partial sets like the cockpit of the Razor Crest, while the surrounding deserts and starfields were digitally projected (Seymour 2020). Physical builds were still necessary, however, to provide actors with objects to touch and interact with, essentially shifting the workforce of physical set design and encouraging more collaboration among departments (Fails 2020).

Figure 2: LED Volume Virtual Production Set. Source: So Stron

Another role that has seen its position and responsibilities shift is location scouts. Traditionally, their role involved scouting real-world sites and making assessments on access, lighting, weather, permits, and logistical concerns. Location manager John Rakich expressed concerns that as the VP becomes more popular, their role would be eliminated (Pennington, 2022). These fears were quickly dispelled as the need for scouting was still necessary, but it would take on a different form. Through VP, location scouts are needed to take 360-degree photographs of locations or even scout for photogrammetry to find textures or materials that can be scaled in LED volumes to manipulate further (Pennigton 2022). Instead of fears of less work, the demand for location scouting has actually increased in the age of Virtual Production.

The shift in responsibilities of creative roles reveals that the VP does not eliminate these roles; it redistributes the duties to reflect the requirements of new technological processes. VP creates hybrid roles that require cross-departmental understanding and collaboration. The next challenge is whether workers receive the training and support needed to thrive in these hybridized environments.

Labor Impacts: Unions and Workforce Development

Virtual production is not only changing roles and workflows in the film industry, but it is also transforming how labor organizations and training programs prepare workers for the future. The speedy adoption of LED volumes and real-time rendering has prompted unions, such as the International Alliance of Theatrical Stage Employees (IATSE), to negotiate how these new tools impact their members’ rights, protections, and skill sets.

In 2021, IATSE nearly staged a nationwide strike over working conditions, long hours, and a lack of protections in emerging production environments (Rose, Berryman, and Elassar 2021). The focus of the recent strike primarily centered on demands for better pay, improved working conditions, and increased contributions to health and pension benefits. However, with the rapid advancement of artificial intelligence (AI) and the rise of virtual productions, IATSE needed to adapt to its union members’ rights. In 2024, IATSE established a new agreement that included provisions acknowledging artificial intelligence as a tool that requires worker consultation and retraining, rather than replacement (Maddaus 2024). Along with the previously stated concerns, the agreement specifies requirements for studios regarding their use of AI technology, including the need to provide workforce training for the AI used (IATSE 2024).

Additionally, independent workforce development initiatives have emerged to address skill gaps. Programs like the Unreal Fellowship, run by Epic Games, train filmmakers and artists to use real-time engines similar to those used in Virtual Production (Unreal Engine). Specific union local chapters, such as IATSE 728, have also introduced workshops to train those working in the film production industry on using LED lighting systems and color manipulation (IATSE 728). These programs demonstrate how both unions and private-sector initiatives are actively preparing workers to embrace the new responsibilities in the virtual production field by adapting to industry changes. The success of these efforts will determine whether workers view Virtual Production as a means for creative empowerment or displacement.

Figure 3: LED Panel Interview Setup. Source: IATSE Local 728

Economic Impacts: Cost, Scalability, and Market Growth

While virtual production has been celebrated for its creative potential, its economic viability can be a challenge. One of the significant costs of VP is building out and operating LED volumes, which require a substantial upfront investment that can cost millions of dollars, excluding labor (Pangilinan 2025). For smaller studios, these costs can be prohibitive; however, there are options to rent studios, which could cost a few hundred thousand dollars, allowing for more accessibility in Virtual Production (Pangilinan 2025).

Even for large-scale productions, questions of scalability are raised. The increased usage of LED volumes has led to “growing pains,” as studios experiment with balancing the high cost of maintaining stages against the benefits they provide (Giardina 2022). These benefits can be significant in the long run as VP minimizes the need for extensive location travel, minimizes physical set construction, and lowers the likelihood of costly reshoots. The economic trade-off provided through VP comes down to the significant capital needed upfront and potential savings across productions in the long term.

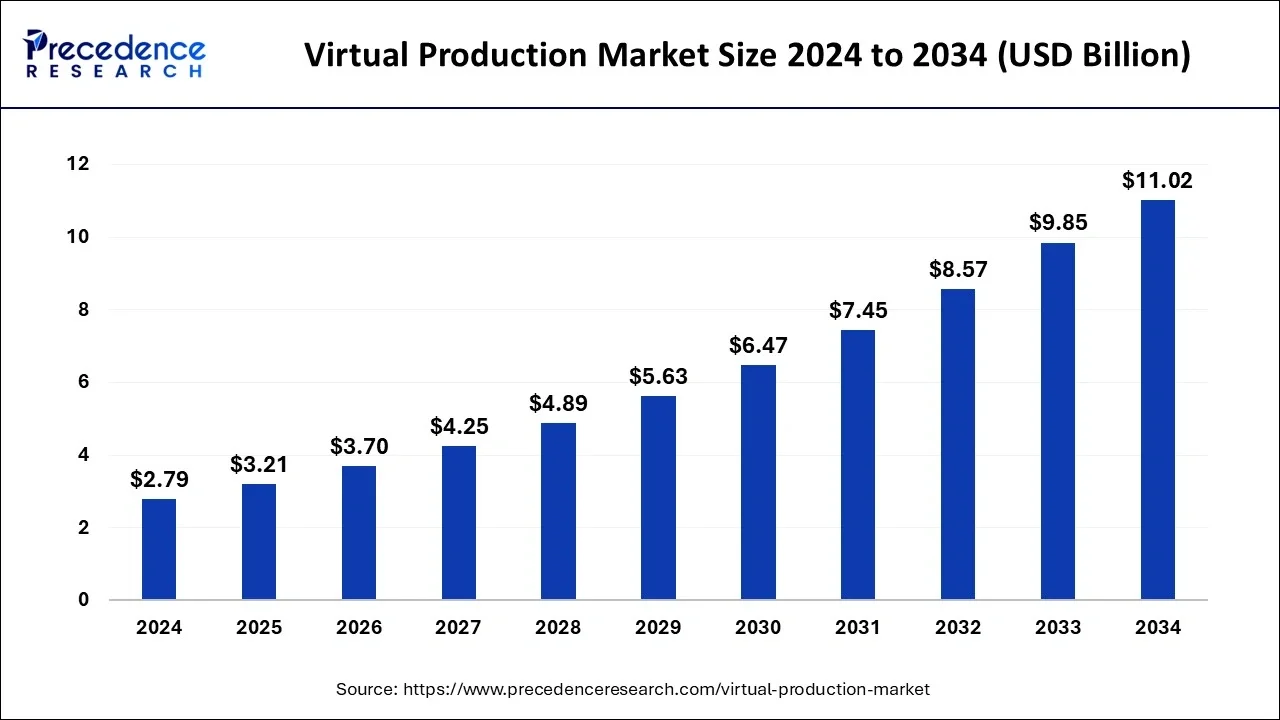

Thus, virtual production is a sector of the film industry with significant growth potential. According to a market forecast conducted by Precedent Research, the VP industry is projected to reach over $11 billion by 2034, driven by increasing adoption across film, television, gaming, and live entertainment (Zoting 2025). North America alone leads the market, accounting for the largest share of 36% in 2024. These projections highlight that VP is not a niche experiment but a growing sector of the entertainment economy.

Figure 4: Virtual Production Market Growth (2024–2034). Source: Precedent Research

Virtual production requires a significant initial investment but provides long-term advantages in a growing industry, particularly in terms of cost management and sustainability by minimizing travel and waste. The key question is whether smaller organizations can access these benefits or if VP will widen the accessibility gap between well-funded studios and independent creators.

Conclusion

Virtual production in the film sector is another innovative iteration of storytelling, leveraging emerging technology and AI renderings of digitally built environments. This growing sector is a catalyst for innovation, where, instead of eliminating jobs, it redistributes creative labor to adjust for the new skills and expertise needed. Labor organizations and training initiatives are adapting to this change, also showing that the future of VP is not opposition but adaptation. The cost-benefit trade-offs reveal that although VP carries high upfront costs, it offers long-term savings through reduced travel, reshoots, and physical set construction. Market projections of more than $11 billion by 2034 show that VP is not a temporary experiment, but a lasting method for producing entertainment.

Overall, virtual production signifies more of a transformation in the production process than a story of job displacement. Its growth highlights the need for investment in training and equity, ensuring that the benefits of this technology are accessible to everyone in the industry. For the creative workforce in production, VP is not merely a new tool; it represents a reorganization of creative labor that will shape the future of filmmaking.

-

DeGuzman, Kyle. 2025. “What Is Virtual Production — Pros, Cons & Process Explained.” StudioBinder, July 2, 2025. https://www.studiobinder.com/blog/what-is-virtual-production-definition/

Fails, Ian. 2020. “The Mandalorian and the Future of Filmmaking.” VFX Voice, October 19, 2020.

https://vfxvoice.com/the-mandalorian-and-the-future-of-filmmaking/Giardina, Carolyn. 2022. “Too Much Volume? The Tech Behind The Mandalorian and House of the Dragon Faces Growing Pains.” The Hollywood Reporter, October 19, 2022.

https://www.hollywoodreporter.com/business/digital/volume-house-of-the-dragon-stage-mandalorian-1235244158IATSE 728. n.d. “Local 728 Training Program.”

https://www.iatse728.org/members/lmsIndustrial Light & Magic. 2020. “The Virtual Production of The Mandalorian Season One.” Video. YouTube.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gUnxzVOs3rkInternational Alliance of Theatrical Stage Employees. 2024. General Memorandum of Agreement of August 1, 2024 Between AMPTP and IATSE, 38–42.

https://www.iatse728.org/sites/default/files/files/MOA%20-%202024%20IATSE%20Basic%20Agreement%20-%20Fully%20Executed.PDFMaddaus, Gene. 2024. “IATSE Agreement Clears the Way to Use Artificial Intelligence as a Tool.” Variety, July 1, 2024.

https://variety.com/2024/biz/news/iatse-agreement-artificial-intelligence-tool-1236057606/Netflix Production Technology Resources. 2022. “Into the Volume: A Behind-the-Scenes Look Into the Virtual Production of 1899.” Video. YouTube.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZMynJCgJIQkPangilinan, Angel. 2025. “How Expensive Is LED Virtual Production? A Cost Breakdown.” CoPilot Co., February 26, 2025.

https://www.copilotco.io/blog-posts/how-expensive-is-led-virtual-productionPennington, Adrian. 2022. “The Impact of Virtual Production on the Role of Location Managers.” Screen Global Production, March 22, 2022.

https://www.screenglobalproduction.com/news/2022/03/22/the-impact-of-virtual-production-on-the-role-of-location-managersRose, Andy, Kimberly Berryman, and Alaa Elassar. 2021. “Union Calls Deal to Avert Strike ‘A Hollywood Ending’ as Negotiations Continue for Workers in Other Parts of Country.” CNN, October 17, 2021.

https://www.cnn.com/2021/10/16/entertainment/union-strike-deal-hollywood-iatse/index.htmlSeymour, Mike. 2020. “Art of LED Wall Virtual Production, Part One: Lessons From The Mandalorian.” Fxguide, March 4, 2020.

https://www.fxguide.com/fxfeatured/art-of-led-wall-virtual-production-part-one-lessons-from-the-mandalorian/Unreal Engine. n.d. “Fellowship.”

https://www.unrealengine.com/en-US/fellowshipZoting, Shivani. 2025. “Virtual Production Market Size to Hit USD 11.02 Bn by 2034.” Precedence Research, July 3, 2025.

https://www.precedenceresearch.com/virtual-production-market