Artificial intelligence (AI) is increasingly being applied in the field of cultural heritage, offering both opportunities and challenges. This article particularly focuses on how AI can be a tool in cultural heritage, and particularly in traditional music. To explore the opportunities and challenges, the subject of this research is the Konghou, also called the Chinese Harp. By examining current models and approaches, along with their limitations, this study aims to demonstrate the evolving intersection between advanced technology and cultural tradition.

Figure 1. Konghou. Image Source: South China Morning Post

There are some controversies regarding the first emergence of Konghou. Some believe it was during the Shang Dynasty (1600-1046 B.C.), while others date it back to the Han Dynasty period (206 BC–AD 220).

Konghou faced its first loss of heritage in the 17th century. Fortunately, In 1964, Konghou was revived in Shenyang, China. Later, during the 1980s, several musical instrument factories in China began to design and produce a new type of Konghou that combined more features of traditional instruments with modern technology.

The number of people learning Konghou in China is extremely limited. Compared to the number of piano learners, a highly popular instrument, the ratio of Konghou learners is only 1:3000. Meanwhile, the Pipa, which itself is considered a niche traditional instrument in China, has 7.8 times more learning it than the Konghou.

Therefore, in our contemporary era, utilizing advanced technology to preserve instruments facing the risk of cultural heritage loss has emerged as a potential solution. Current studies are exploring how digital technologies can effectively address this issue.

Current Gap In AI and Traditional Musical Heritage

Despite some advances in artificial intelligence and music technology, significant gaps remain in the application of AI to traditional musical heritage. One main limitation is the lack of comprehensive and high-quality digital datasets. Since instruments like the Konghou were primarily passed down in ancient times, there are limited archives available after recording technology became more advanced. This lack of documentation makes it difficult for AI models to accurately learn and represent the intricacies of traditional instruments and styles.

Additionally, AI systems often lack the ability to reproduce specific stylistic elements that define traditional music, such as ornamentation in performing, performer’s control over tonality, and culturally-rooted performance practices. For example, the Konghou requires precise techniques for string pressing, plucking, and vibrato to ensure the desired tonal quality. These patterns are difficult to capture algorithmically, as they are often subtle, improvisational, and specific to contexts.

Moreover, there is a notable absence of AI being used in traditional music education. Although AI tools are increasingly entering the field of music education, most existing AI applications remain focused on more mainstream and popular music genres. For example, while some AI tools for accuracy detection have been developed, the vast majority are still not advanced enough to be used in professional instructional contexts.

These technological gaps not only limit preservation efforts but also restrict broader educational access and transmission of traditional musical knowledge. Therefore, it is essential to develop AI tools that are more tailored to traditional music or to find more effective ways of integrating existing AI technologies into traditional musical contexts.

Current Examples: How is Traditional Music Digitized?

To better understand how digital and AI technologies are being applied in the preservation of traditional music, this section presents existing examples across three key areas: sound library, hardware innovation, and generative AI for traditional music. Each example reflects a different approach to digitization and generation, offering insight into the tools already in use or under development, as well as their potential in the arena of traditional music preservation.

Sampled Libraries

Sound Magic offers a comprehensive, 22GB Konghou library featuring over 12,000 samples. Using "hybrid modeling technology," this approach blends deep sampling with modeling, allowing dynamic timbre changes during play for highly expressive and realistic results.

With sound libraries, musicians and producers can virtually recreate the nuanced articulations and dynamic range of rare instruments, like the Konghou, without physical access to the instrument. Moreover, integrating these high-resolution sampled libraries into digital audio workstations (DAWs) allows for more flexibility in a musician’s control over timbre, velocity, and expression, making them useful tools in film scoring, game audio, and contemporary music productions.

However, sound libraries still function primarily as substitutes for real instruments in compositional contexts rather than full replacements. With barely a mouse and keyboard, it is difficult to showcase the virtuosity transferred from real instruments.

Figure 2. Cover image of Sound Magic Konghou Sample Library. Image Source: Neovst, Sound Magic.

Hardware Innovations

In China, a "multifunctional electro-acoustic Konghou" has been prototyped, featuring sensors, signal processors, audio output, displays, and MIDI interfaces for digital control.

Without altering the original functions, features, or style of the traditional guzheng, it enables an expansion of electronic functionalities. In the non-electronic mode, it can still be played like a traditional Konghou. Once switched to electronic mode, the ”electro-acoustic Konghou” can be connected to amplifiers to produce louder sound during performances. In addition, through a MIDI interface connected to a computer, it supports MIDI recording and musical notation, facilitating users in notation and creation.

Case Study: Folk RNN in Irish Music

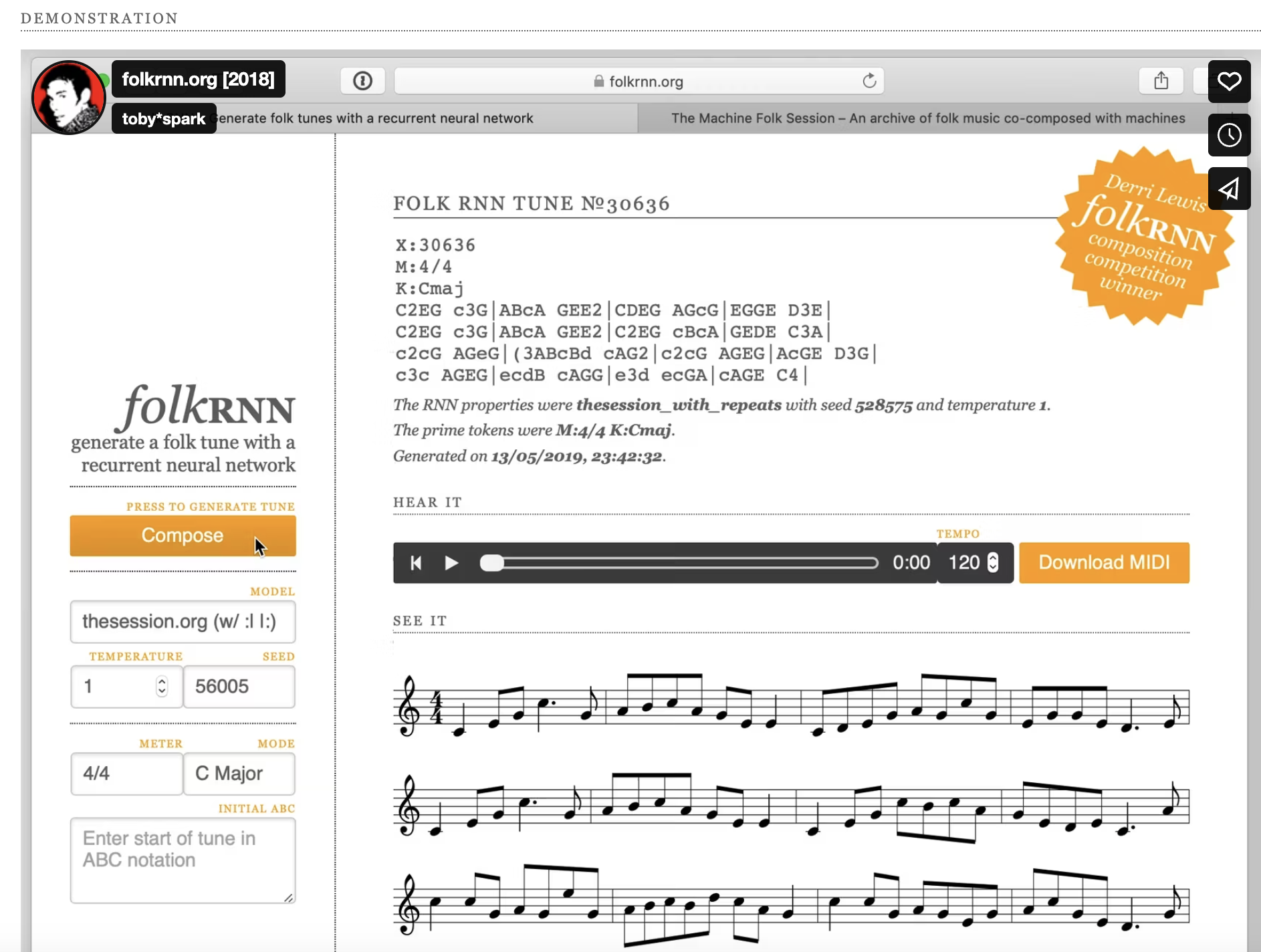

Figure 3. Screenshot of Folk RNN's Demonstration Page. Captured From: folkrnn.org

Folk RNN uses a recurrent neural network (RNN) with Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) units, which is suitable for sequence modeling. The current version of Folk RNN model utilizes a vocabulary of ABC tokens (musical elements like notes, bar lines, ornaments) rather than raw characters. This allowed the network to learn long-term structure (like grouping bars into phrases and phrases into a two-part tune) more effectively than if it generated raw MIDI. In other words, the RNN learned common patterns such as the folk tune structures, repetitions and variations, without being explicitly told to do so. By the end of training, the model will have essentially “learned” the statistical patterns of Irish folk music notation.

The model works by predicting one musical symbol at a time, gathering together melodies that mimic the form and style of traditional folk tunes that it was trained on. Users can also generate new tunes from scratch by selecting meter, mode, and specific style parameters, or “prime” the model with an existing phrase and let it continue.

Folk RNN also has significance in preserving cultural tradition. Having been trained on more than 23,000 music transcriptions and producing more than 10,000 songs, its generated pieces offer musicians a tool for inspiration, composition, and analysis, with a basis of the traditional style. Beyond Irish music, the tool’s success opens possibilities for other folk traditional music, suggesting that AI can serve as a creative support, rather than a replacement. The resource may help expand repertoire and keep musical styles accessible and vibrant in the digital age. The Folk RNN project also demonstrates how AI can effectively learn the patterns and structures of traditional music to generate new compositions that maintain cultural authenticity.

Case Study: MusicMamba

A study from Wuhan University of Technology and Hubei University of Technology in China developed a model based on the MusicMamba architecture, with a specific focus on generation of Chinese traditional music with complex structures and coherent melodies.

The model combines the State Space Model (SSM), which helps in capturing melodic details, with the global structure capturing of the Transformer Block. The generated songs were then analyzed by objective metrics such as Pitch Class Entropy, Groove Consistency, Style Consistency, and Mode Consistency. The result turned out to be exceeding other models including MusicTransformer, Mamba, and Melody T5.

Although the model has not yet been publicly released or applied, its ability to improve long-sequence generation tasks suggests strong potential for generating Chinese traditional music with complex structures and consistent melodies. Given that traditional music often features intricate phrasing, nuanced expression, and extended thematic development, advancements in sequence modeling—particularly those that support stylistic and modal consistency—are especially relevant for this domain.

AI Approaches

Beyond the pre-built generative AI applications mentioned above, most of these tools are powered by underlying generative models that form the foundation of their capabilities. These core AI models are not limited to generating music—they are also widely used in generating text or images, and even for further training of other models. Understanding how these models are structured can help researchers and developers make more informed decisions about which frameworks are best for specific tasks, including the generation of traditional music. The following are some of the most commonly used models: GANs, RNNs, LSTMs, and Google Magenta. These models are adaptable for music generation and may offer valuable potential for traditional music composition.

Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs)

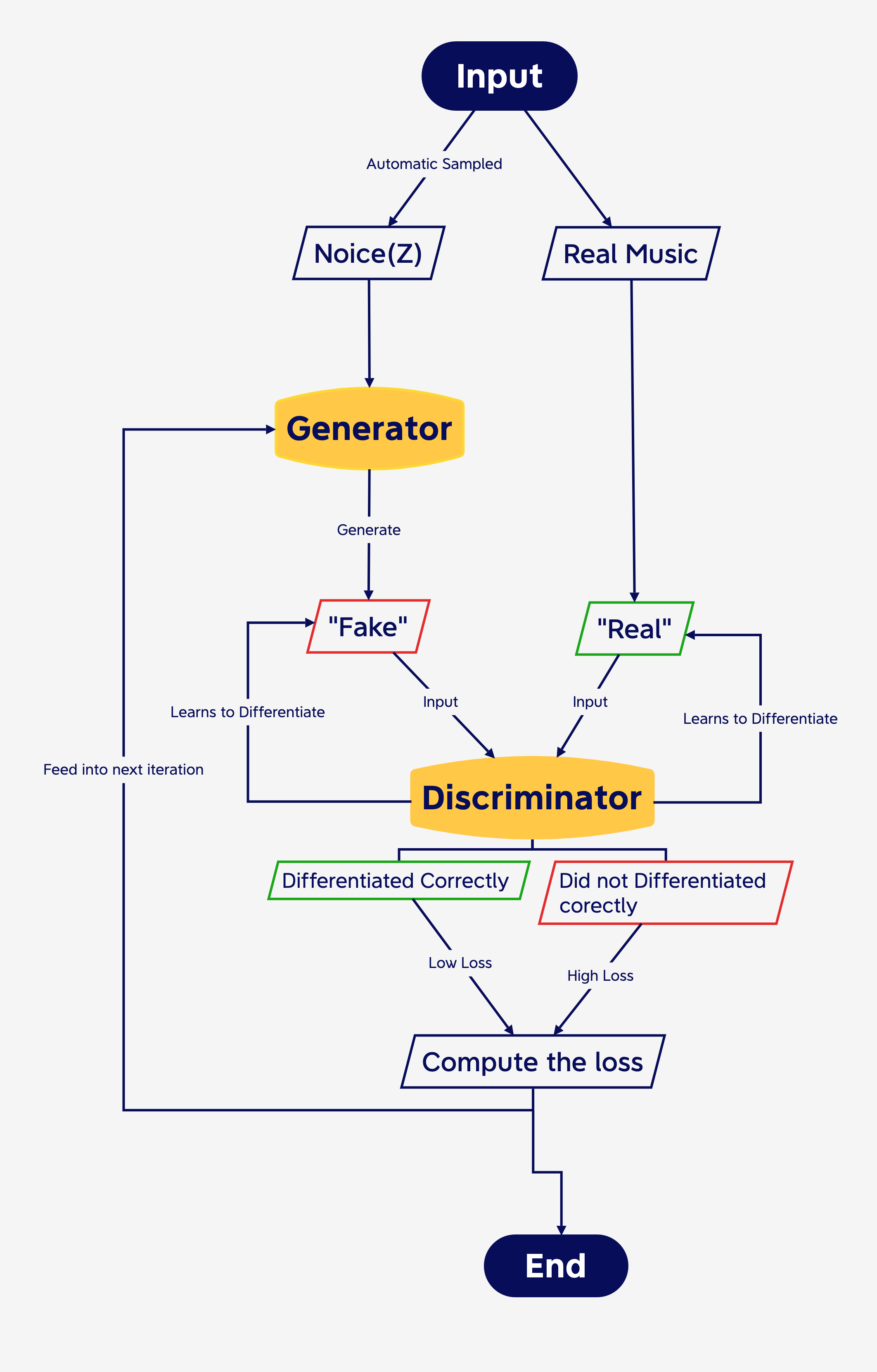

GANs consist of two neural networks with conflicting goals, a Discriminator and a Generator. The discriminator’s task is to determine whether or not input it is given is “real” or “fake.”

The Generator is challenged with creating authentic-looking content that fools the discriminator into believing it’s real. The idea is that when one of these networks gets better at its job, the other network has to learn how to better counteract its adversary. This feedback loop results in obtaining better and better generated content. GANs are more widely used in image generation.

Figure 4. Flow Chart of GAN model. Graphic by Author.

GANs shows great potential for their capability to learn and reproduce complex data distributions, allowing them to identify relationships between music clip sources in a large dataset and generate music that exhibits similar characteristics to the training input. In this way, when trained on traditional music in a niche style, such as Konghou pieces, they have the potential to generate new phrases that mimic traditional idioms or extend them through novel variations in melody or rhythm, while still retaining the instrument’s distinctive sonic identity and cultural integrity.

Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs)

As GAN models are better at capturing overall patterns among music clips, RNNs are more effective at recognizing and reproducing sequences between musical phrases.

Folk RNN, mentioned in the previous section, is a good and straightforward example of RNN model. RNN models have recurrent connections that allow them to maintain an internal state or memory of previous elements in the sequence.

In other words, when processing an element in the sequence, the network considers the current input and information about the preceding elements in the sequence, which is stored in its internal state, a hidden layer of the model. The hidden layer stores past memories, which creates connections that feed back into itself, effectively creating a loop that enables the network to "remember" past information.

Due to these recurrent connections, RNNs can capture interrelationships across the sequencing of input sources. This is a beneficial feature for music generation, as similarities in patterns and structures, even on different modes, usually make music styles identifiable.

Long Short-Term Memory Networks (LSTM)

Compared to RNNs, LSTMs are more detailed, focused on capturing the progression between individual notes.

LSTM is part of the RNN model, but with a more sophisticated architecture. LSTMs use a series of gates to detect which information is relevant to a particular task. LSTM networks use three primary gates – forget, input, and output gates. A time step is finished when all of these gates have been updated.

Inputs of LSTM models are music in machine-readable format – often using Musical Instrument Digital Interface (MIDI) files. These files contain information about notes, chords, durations, and velocities. The data is preprocessed to extract sequences of notes or chords.

The LSTM model is trained on these sequences to learn musical patterns and structures. By processing one note at a time and considering previous notes, the LSTM captures temporal dependencies, enabling it to understand the progression and relationships between notes.

After training, the LSTM can generate new music by predicting subsequent notes based on a given input sequence. The model predicts the next note, appends it to the sequence, and uses this updated sequence to predict the following note. From this feature, LSTM models are suitable for single-track and sequential melody generation.

Figure 5. Flow Chart of LSTM. Graphic by Author.

Magenta and Machine Learning Approaches

The models mentioned above—GANs, RNNs, and LSTMs—represent foundational architectures commonly used in generative AI. In contrast, Google’s Magenta project tends to be somewhere between a fully pre-built tool and a base-level model. It is a more complex framework that can be trained to mimic specific tones and musical patterns, while also being capable of assisting within digital audio workstations, making it more accessible for music production processes.

Google's Magenta project works for music generation by utilizing machine learning and neural network architectures. These networks are trained on large datasets of music to learn the underlying patterns and structures inherent in musical compositions. Once trained, the Magenta models can generate new music based on these learned patterns, creating pieces that can be original and unique.

Under the context of traditional music, Magenta can be seen as an extension of conventional workflows rather than a direct replacement. Musicians can also train the Magenta model to:

Develop new music production software and tools by leveraging Magenta's open-source nature

Interpolate between existing musical ideas to create variations or new phrases

Explore new and innovative compositions based on patterns learned from vast amounts of music data

Besides the model itself, Magenta Studio is an Ableton Live plugin built on Magenta's open-source tools, offering several functionalities for music generation. These include tools like Continue (for extending existing MIDI clips), Groove, Generate (which creates 4-bar phrases without input using a Variational Autoencoder (VAE) trained on millions of melodies and rhythms; Drumify, and Interpolate (for creating transitions between MIDI clips). The Generate tool, in particular, works by choosing a random combination of summarized musical qualities learned by the VAE and decoding it back into MIDI.

Although Ableton Live seems to be the only DAW that supports Magenta Studio, it still makes traditional music composition more accessible in the digital realm. By integrating AI-assisted tools like Magenta, producers and composers can now experiment with melodic generation, rhythm modification, and even how that can apply in live performances. Ultimately, it reflects a broader shift where AI acts as a creative collaborator, empowering artists to push the boundaries of traditional music-making in the digital age.

Conclusion

The ongoing digitization of traditional music reflects a dynamic convergence of cultural preservation and technological innovation. In short, it is a multifaceted process that has great potential for increasing accessibility and innovation—yet it also raises important questions surrounding authenticity and cultural values.

In terms of expanding public access to musical knowledge, AI can act as a bridge between different ways of understanding and experiencing music. By generating songs that follow specific stylistic patterns or structures, AI makes it easier for people to catch a sense of a particular type of traditional music, even when digital archives or resources are limited.

Indeed, AI music generation, especially its application to traditional music, is still evolving. Researchers are continuing to explore solutions for improving long-term coherence in AI-generated compositions. Enhancing the model’s ability to capture subtle nuances and more accurately replicate the expressive qualities of traditional music remains an important direction for its ongoing development. As generative models continue to mature, they will be more helpful in contributing meaningfully to creating new musical works rooted in cultural heritage.

-

A. Gu and T. Dao, “Mamba: Linear-time sequence modeling with selective state spaces,” arXiv preprint arXiv:2312.00752, 2024.

AudioPhiles. “Real Instruments vs VST Plugins.” September 21, 2024. https://audiophiles.co/real-instruments-vs-vst-plugins/

Bi, Huijuan, and Nadia Nasir. “Innovative Approaches to Preserving Intangible Cultural Heritage through AI-Driven Interactive Experiences.” Academic Journal of Science and Technology 12 (2024): 81–84. https://doi.org/10.54097/98nre954.

Britannica. “Konghou.” https://www.britannica.com/art/konghou.

Cain, David. “Unearthing Harmonies: A Journey into the Revival of Ancient Music through AI.” LinkedIn, February 5, 2024. https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/unearthing-harmonies-journey-revival-ancient-music-through-david-cain-csfhc.

ChatGPT (OpenAI, 2024) was used to help develop this newsletter entry.

Chen, Jiatao, Tianming Xie, Xing Tang, Jing Wang, Wenjing Dong, and Bing Shi. “MusicMamba: A Dual-Feature Modeling Approach for Generating Chinese Traditional Music with Modal Precision.” arXiv.Org, 2024. https://doi.org/10.48550/ARXIV.2409.02421.

Chen, Yanxu, Linshu Huang, and Tian Gou. “Applications and Advances of Artificial Intelligence in Music Generation:A Review.” arXiv, September 3, 2024. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2409.03715.

China Today. “The Revival of the Konghou.” April 26, 2021. http://english.chinatoday.com.cn/2018/cs/202104/t20210426_800244879.html.

FolkRNN. “The folk-rnn Project.” Accessed April 1, 2025. https://folkrnn.org/.

Harp Spectrum. “The Chinese Harp—Konghou.” Accessed April 1, 2025. https://www.harpspectrum.org/folk/Chinese_Harp_Konghou.shtml.

Hu Xiaoyang. Utility Model Patent CN202454256U. Filed April 9, 2012, and issued September 26, 2012.

Ian Simon, Curtis Hawthorne, Noam Shazeer, Andrew M. Dai, Matthew D. Hoffman, Monica Dinculescu, and Douglas Eck, “Music transformer: Generating music with long-term structure,” in Proc. Int.Conf. Learn. Represent, pp. 1–14, 2018

J., Ryan T. J. “LSTMs Explained: A Complete, Technically Accurate, Conceptual Guide with Keras.” Medium, March 6, 2024. https://medium.com/analytics-vidhya/lstms-explained-a-complete-technically-accurate-conceptual-guide-with-keras-2a650327e8f2.

Ji, Shulei, Xinyu Yang, and Jing Luo. “A Survey on Deep Learning for Symbolic Music Generation: Representations, Algorithms, Evaluations, and Challenges.” ACM Computing Surveys 56, no. 1 (January 31, 2024): 1–39. https://doi.org/10.1145/3597493.

Kaliakatsos-Papakostas, Maximos, Andreas Floros, and Michael N. Vrahatis. “Artificial Intelligence Methods for Music Generation: A Review and Future Perspectives.” In Nature-Inspired Computation and Swarm Intelligence, edited by Xin-She Yang, 217–245. Academic Press, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-819714-1.00024-5.

“Konghou (Chinese Harp), Xiang Fei Bamboo.” Video blog. The Harp Blog (blog), January 10, 2015. http://www.celticharper.com/harpblog/?tag=video. Accessed May 02, 2025.

“Konghou.” Sound Magic, June 17, 2022. https://neovst.com/product/konghou/.

Li, Yupeng, Jonatan Linberg, and Maria Hedblom. “Music Generation with Generative Adversar- Ial Networks,” n.d.

Li, Rongfeng, and Qin Zhang. “Audio Recognition of Chinese Traditional Instruments Based on Machine Learning.” Cognitive Computation and Systems 4, no. 2 (June 2022): 108–15. https://doi.org/10.1049/ccs2.12047.

Magenta. “Magenta Studio for Ableton Live.” Accessed April 1, 2025. https://magenta.tensorflow.org/studio/ableton-live/.

Mishra, Abhishek. “Understanding Google Magenta: An Overview of Google's Open-Source Music and Art Project.” Medium, March 4, 2023. https://medium.com/@abhishekmishra13k/understanding-google-magenta-an-overview-of-googles-open-source-music-and-art-project-48ea9ee80024.

Nandipati, Mutha, Olukayode Fatoki, and Salil Desai. “Bridging Nanomanufacturing and Artificial Intelligence—A Comprehensive Review.” Materials 17, no. 7 (April 2, 2024): 1621. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma17071621.

Privitera, Adam John, Siew Hiang Sally Ng, Anthony Pak-Hin Kong, and Brendan Stuart Weekes. “AI and Aphasia in the Digital Age: A Critical Review.” Brain Sciences 14, no. 4 (April 16, 2024): 383. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci14040383.

ScienceDirect Topics. “State Space Model.” State Space Model - an overview | Accessed May 2, 2025. https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/social-sciences/state-space-model#:~:text=A%20State%20Space%20Model%20is,the%20previous%20state%20and%20noise.

Shashank K V, Dr. Siddaraju, Rohan A V, Abhijit Nashi, and Sawan Kumar. “Classical Music Generation Using GAN and WaveNet.” Journal of Emerging Technologies and Innovative Research (JETIR) 10, no. 6 (June 2023). https://www.jetir.org.

Shangda Wu, Yashan Wang, Xiaobing Li, Feng Yu, and Maosong Sun, “Melodyt5: A unified score-to-score transformer for symbolic music processing,” 2024.

Sturm, Bob L. T. “Making Sense of The Folk-RNN V2 Model, Part 1.” Folk the Algorithms, December 27, 2017. https://highnoongmt.wordpress.com/2017/12/27/making-sense-of-the-folk-rnn-v2-model-part-1/#:~:text=The%20folk,is%20given%20by%20the%20following.

Sturm, Bob L. T. “On Folk-RNN Cheating And Music Generation.” Folk the Algorithms, June 15, 2017. https://highnoongmt.wordpress.com/2017/06/15/on-folk-rnn-cheating-and-music-generation/#:~:text=Simply%20put%2C%20folk,Tal.

Varun, Joel. “Mamba: Revolutionizing Sequence Modeling With Selective State Spaces.” Medium, January 22, 2024. https://medium.com/@joeajiteshvarun/mamba-revolutionizing-sequence-modeling-with-selective-state-spaces-8a691319b34b.

Yu, Xiaofei, Ning Ma, Lei Zheng, Licheng Wang, and Kai Wang. “Developments and Applications of Artificial Intelligence in Music Education.” Technologies 11, no. 2 (March 16, 2023): 42. https://doi.org/10.3390/technologies11020042.

Zhang, Wenzhuo. “A Phoenix in The Land of The Dragon: The Rebirth of The Konghou in the Neo-Communist Age,” n.d.

Zhou, Ying, and Yuwei Lu. “From Oral Heritage to Digital Code: Philosophical Reflections on the Reconstruction of Traditional Choral Teaching through Artificial Intelligence” 2025 (2025).