Cultural heritage is a testament to millennia of civilization, but it is threatened by natural erosion, tourism, and time. Most traditional methods of conservation, though foundational, have difficulty responding to the scale and complexity of these emerging challenges. Digital technologies, such as artificial intelligence (AI), 3D scanning, virtual reality (VR), and blockchain, can offer new solutions. They make it possible to share cultural assets worldwide, restore them, and archive them permanently. This article examines how digitization preserves and revitalizes cultural property using the Mogao Caves as a case study. It also demonstrates how the international community collaborates to have a beneficial effect.

“A concerted effort to preserve our heritage is a vital link to our cultural, educational, aesthetic, inspirational and economic legacies - all of the things that quite literally make us who we are.”

This article explicates the roles of technology in cultural heritage. This includes a breadth of analysis demonstrating how various countries are currently employing emerging technologies to preserve and promote cultural heritage, while also addressing the associated challenges and opportunities. The article includes a case study of the Mogao Caves in China, illustraing how a single heritage site can integrate a range of advanced technologies and revealing both the potential and the complexities involved in tech-enabled preservation. Finally, the article explores future directions and collaborative models, proposing that interdisciplinary efforts and AI-driven applications may play a key role in advancing the field of heritage preservation.

Cultural heritage

The tangible forms of cultural heritage, such as historical structures, artwork, relics, and archeological sites, are delicate by nature. Based on UNESCO’s research, around 14 primary factors like human activities, transportation infrastructure, climate change, and even pollution continually threaten these irreplaceable treasures.

Ancient frescoes flake and fade, wooden structures decay, and natural disasters or even war can turn once-vibrant locations into ruins. In Syria, for example, relentless war devastated World Heritage sites, “including the Ancient City of Aleppo and its citadel — one of the oldest castles in the world.”

Figure 1. Aleppo before and after. Source: RadioFreeEurope/RadioLiberty

Even in peacetime, hazards abound: a devastating fire at Brazil’s National Museum in 2018 destroyed up to 92.5% of its 20 million artifacts. Although the physical loss was incalculable, Google Arts & Culture still made efforts and worked with the museum to digitally preserve parts of its collection by using technology. As program manager Chance Coughenour said, “Advances in technology — like high-resolution photography, photogrammetry, 3D laser scanning, and virtual and augmented reality — have not only introduced new forms of art, but help us preserve the world's most precious heritage… Even though images cannot replace what has been lost, they offer us a way to remember.”

Traditional preservation methods, such as physical restoration, conservation science, environmental controls, and tourist access restrictions, are still important but frequently struggle to succeed against these powerful threats.

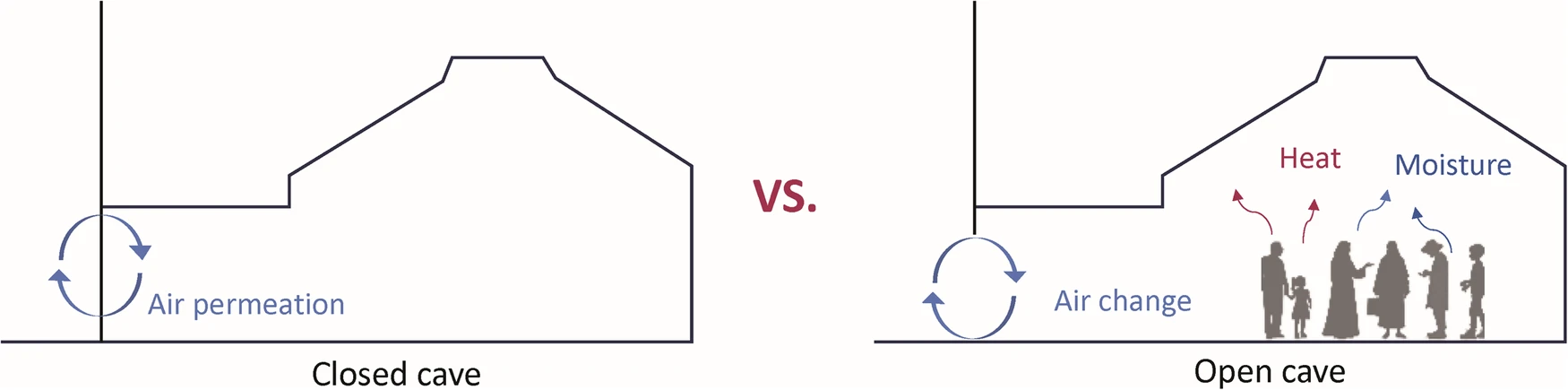

At China's Mogao Caves, conservators strictly monitor factors like wind erosion, humidity, and visitor impact to protect ancient wall paintings. However, balancing broader public access with traditional preservation is a constant challenge. Due to years of wind erosion, the cave's cliff surface has suffered shifting sands and rockfalls, which could bring potential dangers for both the site's sustainability and its visitors. Severe weather has also made the cave's humidity levels more extreme, which has harmed the murals by causing problems like efflorescence and flaking.

To manage these risks, sometimes authorities had to close caves or limit visitor numbers, exposing the limitations of relying solely on physical protection. To put it briefly, the preservation of cultural assets on site or in archives is a race against time that humanity hasn't always won.

Figure 2. “Visitor impacts on cave environments” Source: npj | heritage science

Emerging digital technologies are bringing new hope to cultural heritage preservation

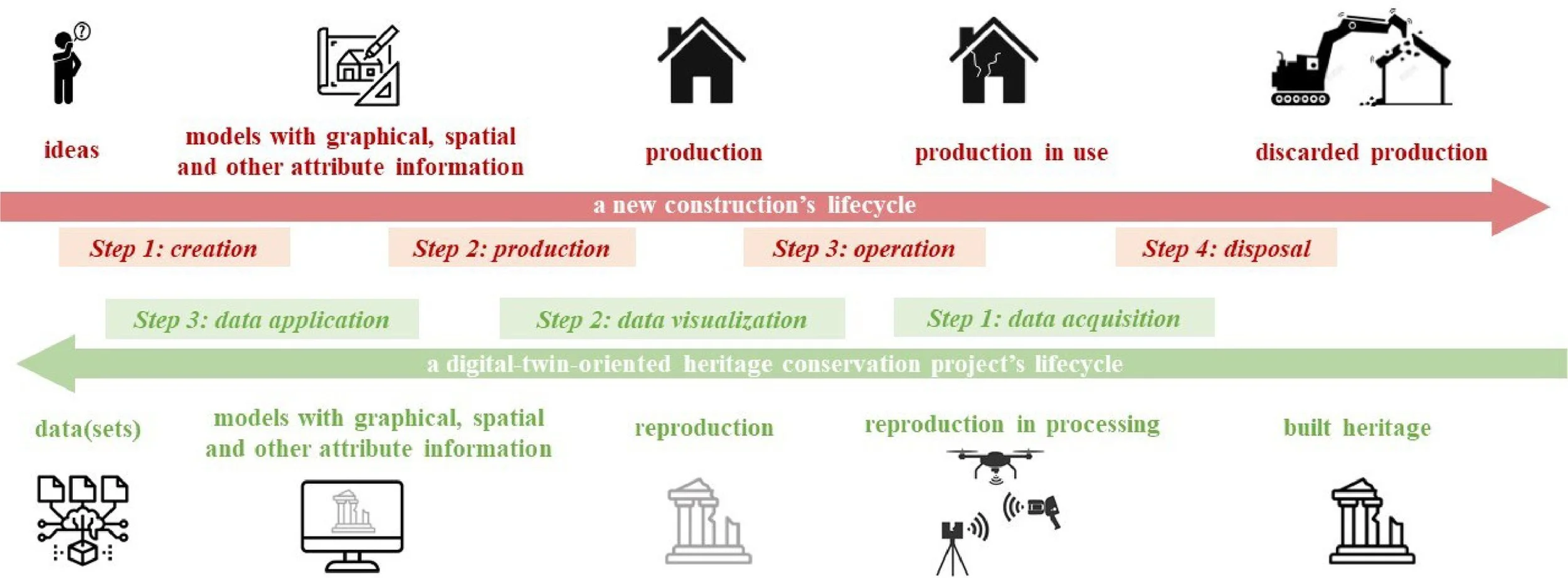

In the past few decades, tools like 3D scanning, virtual reality (VR), artificial intelligence (AI), and blockchain have developed ways that we protect and share cultural memory. These tools help create accurate digital copies and backups of heritage sites and artifacts.

Digitization allows us to preserve fragile artworks and let people explore historic places through immersive media without risking physical damage to the originals. These technologies are not only helping preserve heritage but also making museums and cultural sites more accessible to broader audiences.

Figure 3. Lifecycle Comparison: Digital Twin vs. New Construction. Source: ScienceDirect

3D Scanning and High-Precision Digitization

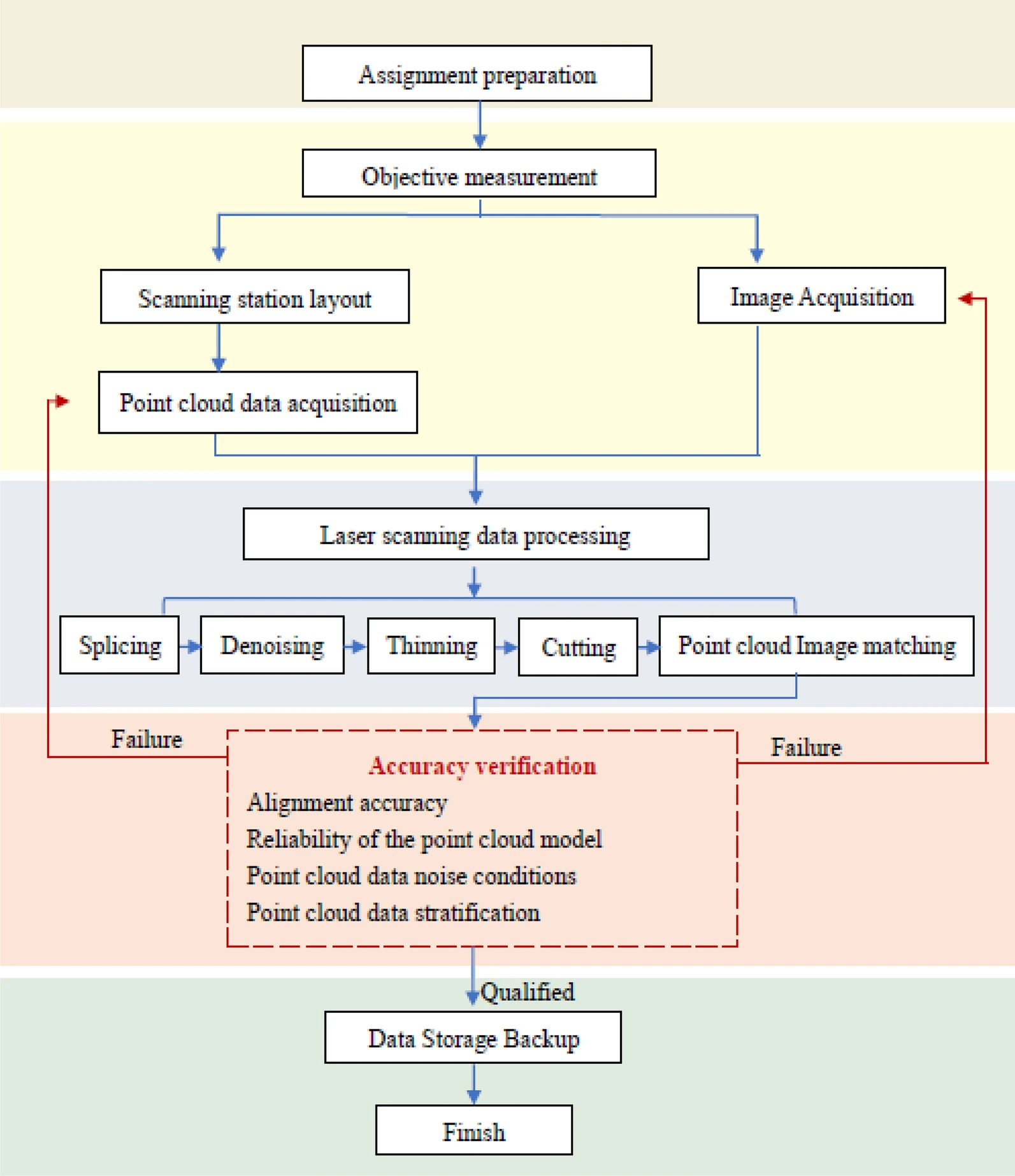

3D scanning is like taking a digital "mold" of an object without ever touching it. Think of it as creating a perfect digital twin of a cultural artifact that can be studied, shared, and preserved forever. Documentation and recording are the first steps in the preservation process. Instead of spending several months meticulously hand-drawing artifacts, researchers can use 3D scanning and modeling tools to revolutionize the process by increasing efficiency, enhancing accuracy, and minimizing contact with delicate objects at the same time. This digital revolution is happening across museums and heritage sites worldwide. There are four main technologies that capture the physical world in digital form:

Light Detection and Ranging (LiDAR) is like thousands of invisible measuring tapes working simultaneously. The scanner emits a laser beam that reflects off the surface and returns to the device. By calculating the return time of each laser beam, the scanner can create what is called a “point cloud,” millions of accurately measured three-dimensional points in space that make up a detailed digital replica of the object. It’s ideal for capturing large structures like temple facades or entire archaeological sites.

Figure 4. Workflow of 3D Laser Scanning Process. Source: Nature

Figure 5. Visual comparison of five digitized cultural heritage sites. Source: Hung-Ming Cheng, Ya-Ning Yen, Min-Bin Chen, and Wun-Bin Yang, "A Processing for Digitizing Historical Architecture," China University of Technology.

Photogrammetry can identify common points across images and use math to calculate their 3D positions by taking many overlapping pictures from different angles. This transforms regular photographs into accurate 3D models. It is budget-friendly and especially useful for field documentation.

Structured Light Scanning projects patterns (usually stripes or grids) onto an object. When these patterns hit the surface, they deform based on the object's shape. Special cameras capture these deformations, and algorithms convert them into detailed 3D data. Museums and heritage organizations often use this technology as a complementary tool for LiDAR. Unlike LiDAR, which can scan entire building and surrounding area, structured light scanning can capture fine details on smaller artifacts like coins or jewelry.

Figure 7. A step-by-step virtual restoration of a fragmented clay Buddha face using 3D scanning and digital reconstruction techniques. Source: EinScan

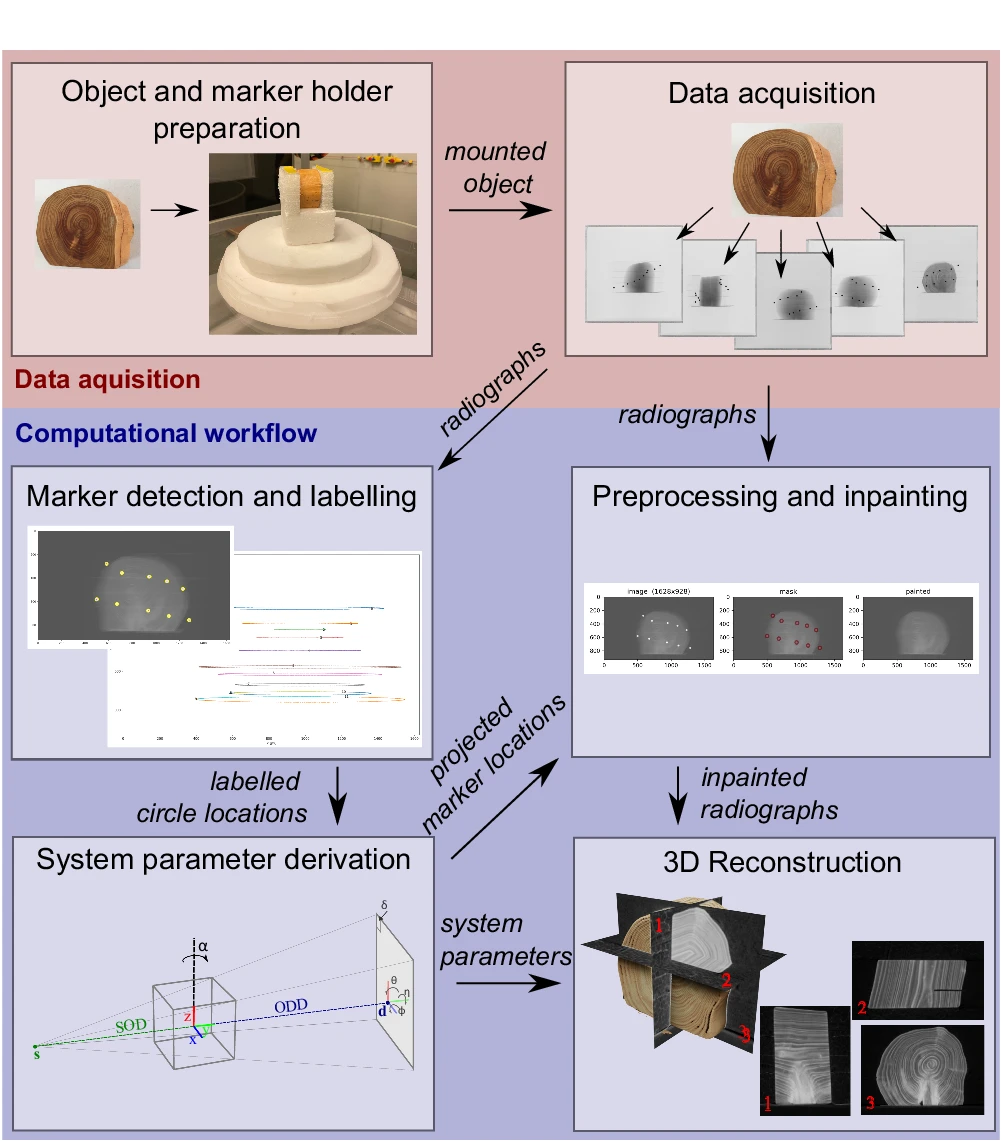

CT Scanning uses X-rays to see inside objects without damaging them. Similar to medical CT scans, the process involves rotating X-ray sources and detectors around the object, creating cross-sectional images that are then stacked to form a complete 3D model. This technology is revolutionary for examining the internal structure of artifacts that cannot be opened or disassembled, such as sealed ancient scrolls, mummies, or composite artifacts. CT scans can reveal hidden details that cannot be seen by the naked eye, helping researchers understand construction techniques and internal damage without any physical intervention.

Figure 8. A step-by-step process for creating a 3D model using CT scans. Source: Nature Communications

AI-Assisted Analysis and Machine Learning

These tools are effective, but imagine having a digital assistant that can learn from experience and recognize patterns that even trained experts might miss. That's what AI and machine learning bring to cultural heritage preservation.

Artificial Intelligence (AI) lets computers do tasks that normally need human intelligence. This includes recognizing images, understanding speech, making decisions, and solving problems. Think of AI as the overarching goal to make machines "smart." Machine Learning (ML) is how we actually teach computers to be smart. Instead of programming specific instructions for every task, we feed the computer lots of examples and let it learn patterns by itself. For instance, if you show a computer thousands of photos of cats and dogs, it learns to tell them apart without being explicitly programmed what makes a cat different from a dog.

The application of AI and machine learning has been changed from basic “Linear Regression analysis to complex Deep Learning models." These smart computer systems can study thousands of examples to learn what damage on a mural looks like, how to virtually restore faded colors, or how to piece together fragments of ancient texts. While traditional conservation relies on the human eye and expertise, AI can analyze millions of data points in seconds, detecting subtle changes in condition that signal early deterioration before it becomes visible.

Long-term Preservation and Authentication Technologies

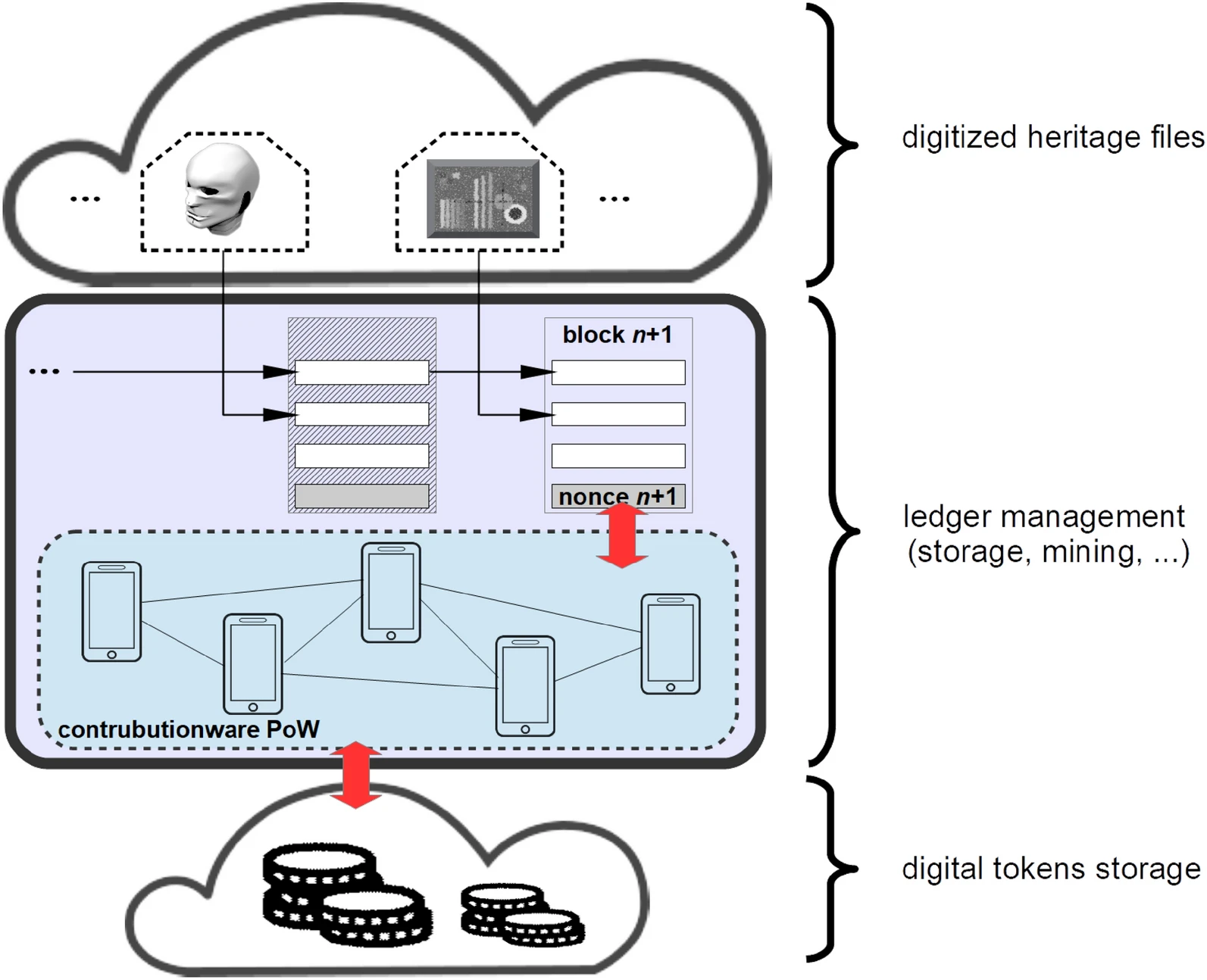

Blockchain might sound like financial tech jargon, but it's solving one of heritage's oldest problems: proving what's real and tracking where it's been. The role of blockchain in cultural heritage protection is essentially a distributed digital ledger. The origin, ownership change, exhibition history, and restoration records of each cultural relic are permanently recorded on multiple computers. Using blockchain is like establishing a complete “digital ID card” system to ensure the important information cannot be modified or deleted by anyone. NFTs (non-fungible tokens) are unique digital asset certificates based on blockchain technology. Museums can sell NFTs related to cultural relics to raise funds for restoration. For example, issue digital collectible NFTs of specific murals, and use the income for mural protection. Together, they provide a reliable and transparent digital protection solution for cultural heritage.

The Emerging Tech podcast episode "Bridging Art and Blockchain, Bringing Certification to Woo with Robert Norton" featuring Verisart CEO Robert Norton offers valuable insights into this topic. The episode touches on how blockchain technology creates trust and authenticity in the art world, the evolution from digital limited editions to NFTs, and how this technology is revolutionizing art authentication and preservation. Key takeaways include how Verisart is using blockchain to combat art forgery and create transparent provenance records, ultimately democratizing access to art certification and preservation.

Figure 9. Using blockchain to store and protect digital heritage files. Source: Nature

Case studies

Even though each emerging technology is powerful, cultural heritage preservation projects in reality often combine multiple technologies together to create comprehensive solutions. Leading art and technology institutions show how this integrated approach can transform our understanding and experience of cultural heritage.

Harvard CAMLab

Harvard University’s CAMLab is a great example of this multi-technical integration through its Cave Dance project. They combined machine learning algorithms to analyze ancient dance murals, used motion capture technology to bring static characters to life with professional dancers, used VR experiences to immerse visitors in reconstructed cave environments, and combined immersive installations with interactive media to tell rich cultural stories. This technological combination has created a comprehensive digital ecosystem that not only protects Buddhist art and architecture but also actively reshapes them for contemporary audiences.

UChicago DCADP

Similarly, the University of Chicago’s Dispersed Chinese Art Digitization Project (DCADP) uses advanced 3D scanning technology to capture scattered Chinese artifacts from museums around the world, digital modeling technology to virtually restore architectural elements, a complex database system to manage global artifact information, and virtual reconstruction technology to reassemble physically separated cultural treasures in their original environments. The DCADP overcomes geographic limitations and digitally reassembles China's dispersed cultural legacy.

Mogao Caves

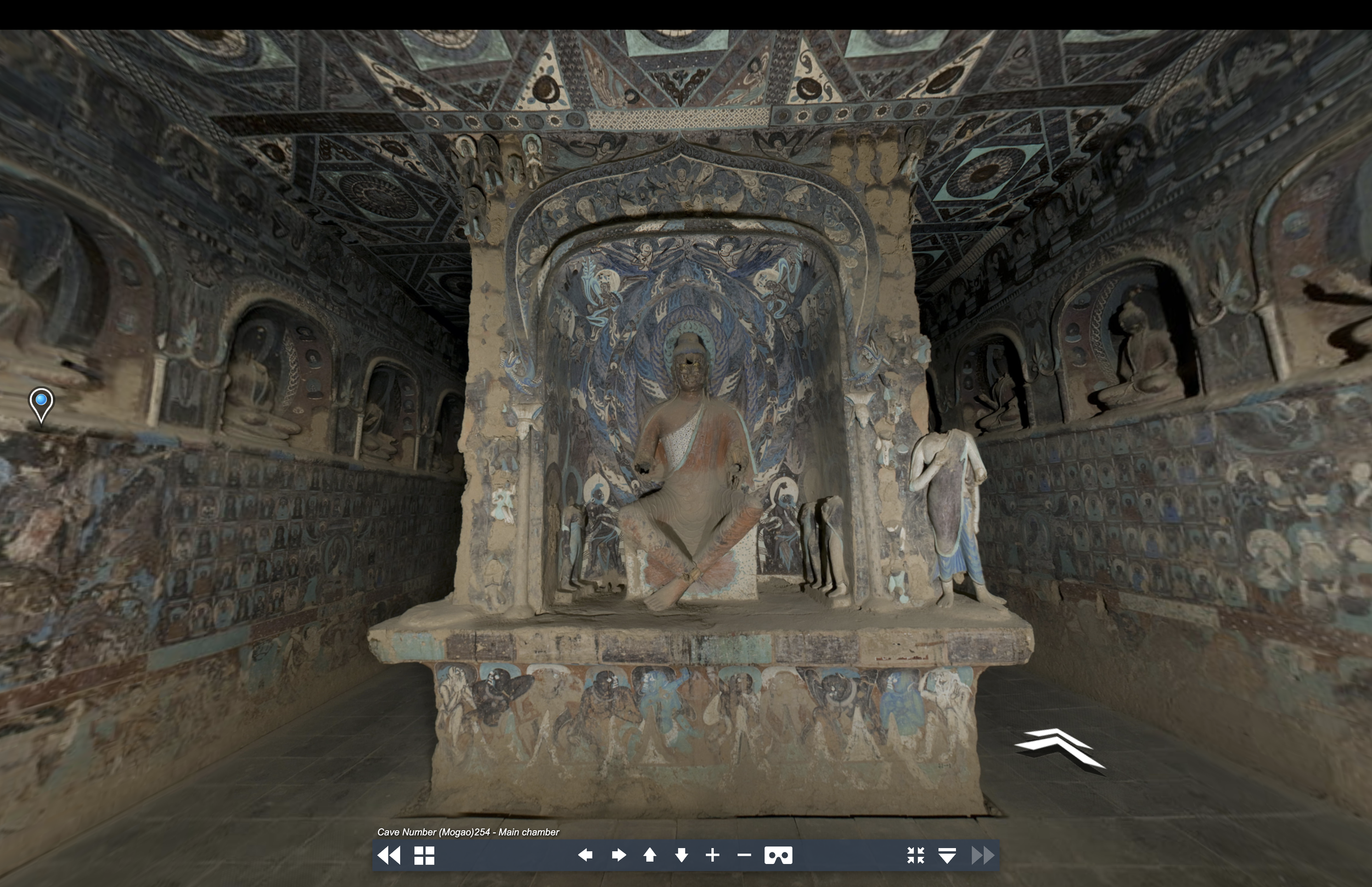

The Dunhuang Mogao Caves, a UNESCO World Heritage Site, are one of humanity’s great cultural treasures. These 735 caves, which date from the fourth to the fourteenth centuries, are built on cliffs in the Dunhuang desert, in the northwest part of China. These caves are home to breathtaking Buddhist artworks, including 45,000 square meters of vivid murals, intricately crafted sculptures, and manuscripts documenting the cultural exchanges along the Silk Road.

To protect this legacy legally, the Dunhuang Academy, China’s first state-funded conservation institution, was established in 1944. The Dunhuang Academy has transformed how we protect the Mogao Caves through smart use of technology. They started the "Digital Dunhuang" project, which uses high-tech cameras and 3D scanning to create perfect digital copies of 735 caves, capturing every tiny detail of 45,000 square meters of murals and 2,400 sculptures.

Figure 10. A digital panoramic view of Mogao Cave 254. This interactive visualization allows users to explore the cave interior by following directional arrows, revealing murals and sculptures from multiple angles. Source: Screenshot from Digital Dunhuang

The Academy works with big tech companies like Tencent to create virtual reality experiences, letting people explore caves digitally without damaging the real ones. They've built a Digital Exhibition Center where visitors can see life-size digital copies of the caves using projection technology. This means fewer people need to enter the fragile original caves.

They have collaborated to develop a blockchain-based Digital Dunhuang Material Library and co-creation platform. The platform not only hosts high-definition digital assets but also enables a co-creation model that allows individual and enterprise creators to download materials for their own creative works. As a leading Chinese gaming company, Tencent has also created "Jiayao," the first digital avatar and ambassador for Dunhuang culture, bringing this ancient heritage to life in a more engaging way.

Figure 11. Jiayao, a virtual dancer developed with real-time rendering and motion capture technology. Source: Tencent Games – Technology Empowers Culture

These innovative projects prove that the future of cultural heritage conservation does not depend on a single technology, but somewhat on combining multiple emerging technologies to provide digital solutions that meet complex conservation needs.

Challenges & opportunities

While new technologies offer innovative solutions for heritage conservation, they also bring potential challenges. Cultural heritage sites face several real problems when trying to use new digital tools. On the technical side, equipment and software quickly become outdated. The legal ownership of digital reproductions of artifacts is also unpredictable, and global cooperation is challenging due to different international regulations.

Money is a major concern because most cultural organizations and institutions have tight resources and budgets, and these new technologies are expensive to get and maintain. The remaining human challenges include encouraging constructive departmental collaboration, convincing traditionalists to adopt new methods, and helping staff learn new abilities. These challenges show that sustainable digital preservation requires more than just high-tech tools; it requires institutions to change how they operate and think about heritage preservation.

Future applications

Integrating emerging technologies into cultural heritage preservation requires interdisciplinary collaboration around the world. Historians, conservators, AI researchers, and technologists should work together to ensure that innovations serve both cultural and technical goals.

Future applications of these technologies could transform how we protect and interact with heritage sites worldwide. Advanced AI systems may help predict when ancient buildings are at risk by identifying early signs of structural damage. This would allow conservators to take action before any real visible deterioration occurs.

Digital twins of entire historical districts could allow urban planners to simulate the impact of modern development on heritage sites. Blockchain technology might create a global shared network digital platform for tracking dispersed artifacts, establishing secure provenance records for museums and collectors. Extended reality formats could democratize access by creating virtual museums that combine collections from different countries, while haptic technology might allow people to "touch" ancient artifacts safely. What’s more, advanced robotics could assist in delicate restoration work, performing tasks with microscopic precision that exceed human capabilities. These innovations suggest a future where technology not only protects heritage but also actively enhances our connection to it.

Figure 12. The Future of Art, a virtual NFT art gallery concept exploring immersive exhibition spaces powered by Web3 and generative AI. Source: Forbes

conclusion

Digital technology has become a powerful tool in the effort to protect cultural heritage around the world. However, it is essential to remember that technology should serve culture. We should support the goal of preserving historical authenticity while also encouraging innovation. The most effective digital transformations do not try to replace traditional conservation practices. Instead, they enhance and expand what is already possible. They open new ways to document, study, and share cultural heritage that would otherwise remain hidden or at risk. When applied thoughtfully, digital methods can help cultural heritage move beyond the limits of physical survival and enter a new era of “digital immortality" and preserve the memory of civilization for future generations.

-

Braun, Stuart. “Can Syria’s Devastated Cultural Heritage Be Rebuilt?” Culture. DW broadcaster, December 19, 2024. https://www.dw.com/en/can-syrias-devastated-cultural-heritage-be-rebuilt/a-71096112.

Buragohain, Dipima, Yahui Meng, Chaoqun Deng, Qirui Li, and Sushank Chaudhary. “Digitalizing Cultural Heritage through Metaverse Applications: Challenges, Opportunities, and Strategies.” Heritage Science 12, no. 1 (August 13, 2024): 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40494-024-01403-1.

Cao, Jianfang, Yanfei Li, Hongyan Cui, and Qi Zhang. “Improved Region Growing Algorithm for the Calibration of Flaking Deterioration in Ancient Temple Murals.” Heritage Science 6, no. 1 (November 27, 2018): 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40494-018-0235-9.

Chen, Yuangao, Xini Wang, Bin Le, and Lu Wang. “Why People Use Augmented Reality in Heritage Museums: A Socio-Technical Perspective.” Heritage Science 12, no. 1 (April 3, 2024): 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40494-024-01217-1.

Conserving Wall Paintings in Cave 85 at the Mogao Cave Temples, 2016. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DZUc6LrAq0A.

Dang, Xinyuan, Wanqin Liu, Qingyuan Hong, Yibo Wang, and Xuemin Chen. “Digital Twin Applications on Cultural World Heritage Sites in China: A State-of-the-Art Overview.” Journal of Cultural Heritage 64 (November 1, 2023): 228–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.culher.2023.10.005.

Deng, Zhangyu. “Mogao Caves Joins VR Show Trend to Enhance Experience, Improve Preservation.” Society. China Daily, July 3, 2024. https://www.chinadaily.com.cn/a/202407/03/WS66849f6ea31095c51c50c03a.html.

Emerging Tech Podcast. “Blockchain Art Certification and NFTs with Robert Norton.” Do the Woo Media Channel, July 31, 2024. https://dothewoo.io/bridging-art-and-blockchain-bringing-certification-to-woo-with-robert-norton/.

Falcone, M., A. Origlia, M. Campi, and S. DI Martino. “From Architectural Survey to Continuous Monitoring: Graph-Based Data Management for Cultural Heritage Conservation with Digital Twins,” 43:47–53, 2021. https://doi.org/10.5194/isprs-archives-XLIII-B4-2021-47-2021.

Fang, Aiqing. “Gaming Technology Enables Worldwide Culture Sharing.” FOCUS - Life&Art. chinadailyhk, June 3, 2024. https://www.chinadailyhk.com/hk/article/584769#Gaming-technology-enables-worldwide-culture-sharing--2024-06-03.

Fiorucci, Marco, Marina Khoroshiltseva, Massimiliano Pontil, Arianna Traviglia, Alessio Del Bue, and Stuart James. “Machine Learning for Cultural Heritage: A Survey.” Pattern Recognition Letters 133 (May 1, 2020): 102–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.patrec.2020.02.017.

Ghaith, Kholoud. “AI Integration in Cultural Heritage Conservation – Ethical Considerations and the Human Imperative.” International Journal of Emerging and Disruptive Innovation in Education : VISIONARIUM 2, no. 1 (June 3, 2024): Article 6. https://doi.org/10.62608/2831-3550.1022.

GT staff reporters. “Virtual Mogao Caves Show the World Strengths of Digitizing Relics - Global Times.” Life | Culture. Global Times, May 15, 2024. https://www.globaltimes.cn/page/202405/1312380.shtml.

Harisanty, Dessy, Kathleen Lourdes Ballesteros Obille, Nove E. Variant Anna, Endah Purwanti, and Fitri Retrialisca. “Cultural Heritage Preservation in the Digital Age, Harnessing Artificial Intelligence for the Future: A Bibliometric Analysis.” Digital Library Perspectives 40, no. 4 (September 20, 2024): 609–30. https://doi.org/10.1108/DLP-01-2024-0018.

He, Tong-Liang, and Feng Qin. “Exploring How the Metaverse of Cultural Heritage (MCH) Influences Users’ Intentions to Experience Offline: A Two-Stage SEM-ANN Analysis.” Heritage Science 12, no. 1 (June 12, 2024): 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40494-024-01315-0.

Hu, Xueqing, Ruobin Wu, Yonghui Li, Huarong Xie, Zhengmo Zhang, Shuichi Hokoi, and Bomin Su. “Impact of Opening the Entrance on Cave Temple Murals in Different Climate Zones for Preventive Conservation.” Npj Heritage Science 13, no. 1 (April 1, 2025): 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1038/s40494-025-01555-8.

Khelifi, Adel, Mark Altaweel, Mohammad Hashir, Tasoula Hadjitofi, and Mohammad Ghazal. “Salsal: Blockchain for Vetting Cultural Object Collections.” Heritage Science 12, no. 1 (January 11, 2024): 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40494-023-01129-6.

Li, Cathy. “The Future of History: How Digital Dunhuang Revitalizes Cultural Heritage.” Asia IP, October 31, 2024. https://asiaiplaw.com/article/the-future-of-history-how-digital-dunhuang-revitalizes-cultural-heritage.

Li, Fengling, and Shengping Xia. “International Cooperation in the Digital Preservation of the Cultural Heritage of the Dunhuang Mogao Grottoes.” Library Trends 71, no. 3 (2023): 345–63.

Li, Weicong, Qian Xie, Jinghui Ao, Haopai Lin, Shanshan Ji, Mengsi Yang, and Jiahui Sun. “Systematic Review: A Scientometric Analysis of the Status, Trends and Challenges in the Application of Digital Technology to Cultural Heritage Conservation (2019–2024).” Npj Heritage Science 13, no. 1 (March 28, 2025): 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1038/s40494-025-01636-8.

Liu, Qing, Amer Shakir Zainol, and Nurul Huda Mohd Din. “Research on Digital Cultural Products of the Dunhuang Mogao Grottoes.” Asian Journal of Research in Education and Social Sciences 6, no. 3 (September 30, 2024): 489–96.

Liu, Zhen, Silu Liu, and Shuo Fan. “Research on the Virtual Restoration of Faded Dunhuang Murals with a Global Attention Mechanism.” Npj Heritage Science 13, no. 1 (February 24, 2025): 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1038/s40494-025-01592-3.

Mendoza, M.A.D., J.E.G. Gómez, and E. De La Hoz Franco. “Technologies for the Preservation of Cultural Heritage—A Systematic Review of the Literature.” ResearchGate, January 6, 2023. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15021059.

Migliorini, Sara, Mauro Gambini, and Alberto Belussi. “A Blockchain-Based Platform for Ensuring Provenance and Traceability of Donations for Cultural Heritage.” Blockchain: Research and Applications, March 21, 2025, 100278. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bcra.2025.100278.

Mu, Rongxuan, Yuhe Nie, Kent Cao, Ruoxin You, Yinzong Wei, and Xin Tong. “Pilgrimage to Pureland: Art, Perception and the Wutai Mural VR Reconstruction.” arXiv, April 15, 2023. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2304.07511.

Newcomb, Alyssa. “Brazilian Museum Destroyed by Fire Lives on through Google.” BUSINESS NEWS. NBC News, December 19, 2018. https://www.nbcnews.com/business/business-news/brazilian-museum-destroyed-fire-lives-through-google-n949361.

Niu, Yuhan. “The Mogao Caves: Preserving Cultural Heritage in a Changing Climate.” PreventionWeb, October 31, 2023. https://www.preventionweb.net/news/mogao-caves-preserving-cultural-heritage-changing-climate.

Oh, Je-Ho, and Chung-Kon Shi. “Interactive Human: Seen through Digital Art.” In 2013 International Conference on Culture and Computing, 188–89, 2013. https://doi.org/10.1109/CultureComputing.2013.58.

Okanovic, Vensada, Ivona Ivkovic-Kihic, Dusanka Boskovic, Bojan Mijatovic, Irfan Prazina, Edo Skaljo, and Selma Rizvic. “Interaction in eXtended Reality Applications for Cultural Heritage.” Applied Sciences 12, no. 3 (January 2022): 1241. https://doi.org/10.3390/app12031241.

Oladokun, Bolaji David, Yusuf Ayodeji Ajani, Bernadette C. N. Ukaegbu, and Emmanuel Adeniyi Oloniruha. “Cultural Preservation Through Immersive Technology: The Metaverse as a Pathway to the Past.” Preservation, Digital Technology & Culture 53, no. 3 (October 1, 2024): 157–64. https://doi.org/10.1515/pdtc-2024-0015.

Prados-Peña, María Belén, George Pavlidis, and Ana García-López. “New Technologies for the Conservation and Preservation of Cultural Heritage through a Bibliometric Analysis.” Journal of Cultural Heritage Management and Sustainable Development ahead-of-print, no. ahead-of-print (March 23, 2023). https://doi.org/10.1108/JCHMSD-07-2022-0124.

Runze, Yang. “A Study on the Spatial Distribution and Historical Evolution of Grotto Heritage: A Case Study of Gansu Province, China.” Heritage Science 11, no. 1 (August 2, 2023): 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40494-023-01014-2.

Sheng, Wang, Susumu Nakata, Satoshi Tanaka, Hiromi H. Tanaka, and Akihiro Tsukamoto. “Modeling High-Quality and Game-Like Virtual Space of a Court Noble House by Using 3D Game Engine.” In 2013 International Conference on Culture and Computing, 212–13, 2013. https://doi.org/10.1109/CultureComputing.2013.70.

Shinning 3D.com. “The Future of Heritage Preservation through High-Quality 3D Scanning.” Case Studies, March 16, 2023. https://www.shining3d.com/the-future-of-heritage-preservation-through-high-quality-3d-scanning.

Shui, Biwen, Zongren Yu, Qiang Cui, Zhuo Wang, Zhiyuan Yin, Manli Sun, and Boming Su. “Blue Pigments in Cave 256, Mogao Grottoes: A Systematic Analysis of Murals and Statues in Five Dynasties, Song Dynasty and Qing Dynasty.” Heritage Science 10, no. 1 (June 18, 2022): 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40494-022-00722-5.

Skublewska-Paszkowska, Maria, Marek Milosz, Pawel Powroznik, and Edyta Lukasik. “3D Technologies for Intangible Cultural Heritage Preservation—Literature Review for Selected Databases.” Heritage Science 10, no. 1 (January 4, 2022): 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40494-021-00633-x.

Song, Zhuyun. “Gaining Instead of Losing: The Image of Dunhuang as a Religious Heritage in a WeChat Mini-Programme.” Religions 14, no. 5 (May 2023): 634. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14050634.

Stoean, Ruxandra, Nebojsa Bacanin, Catalin Stoean, and Leonard Ionescu. “Bridging the Past and Present: AI-Driven 3D Restoration of Degraded Artefacts for Museum Digital Display.” Journal of Cultural Heritage 69 (September 1, 2024): 18–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.culher.2024.07.008.

Stublić, Helena, Matea Bilogrivić, and Goran Zlodi. “Blockchain and NFTs in the Cultural Heritage Domain: A Review of Current Research Topics.” Heritage 6, no. 4 (April 2023): 3801–19. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage6040202.

Sun, Tongxin, Tongtong Jin, Yuru Huang, Meng Li, Yun Wang, Zhe Jia, and Xinyi Fu. “Restoring Dunhuang Murals: Crafting Cultural Heritage Preservation Knowledge into Immersive Virtual Reality Experience Design.” International Journal of Human–Computer Interaction 40, no. 8 (April 17, 2024): 2019–40. https://doi.org/10.1080/10447318.2023.2232976.

Tang, Yuchen, Liu Liu, Tianbo Pan, and Zhangxu Wu. “A Bibliometric Analysis of Cultural Heritage Visualisation Based on Web of Science from 1998 to 2023: A Literature Overview.” Humanities and Social Sciences Communications 11, no. 1 (August 24, 2024): 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-03567-4.

Taylor, Kelsey, and Eric Brelsford. “Telling the Story of Changing Populations With Mapping Historical New York: A Digital Atlas.” Blog. Stamen, October 24, 2024. https://stamen.com/telling-the-story-of-changing-populations-with-mapping-historical-new-york-a-digital-atlas/.

Tencent.com. “Tencent Blockchain Makes Over 6,500 Artworks from Dunhuang Caves Accessible to the Public for the First Time.” Media | Tecent Perspectives, December 8, 2022. https://www.tencent.com/en-us/articles/2201492.html.

Tencent.com. “Tencent’s Game Technology Brings Mogao Grottoes to Life, Revitalizing Ancient Culture in Immersive Experience.” Media | Corporate News, April 18, 2024. https://www.tencent.com/en-us/articles/2201835.html?utm_source=chatgpt.com.

Tiribelli, Simona, Sofia Pansoni, Emanuele Frontoni, and Benedetta Giovanola. “Ethics of Artificial Intelligence for Cultural Heritage: Opportunities and Challenges.” IEEE Transactions on Technology and Society 5, no. 3 (September 2024): 293–305. https://doi.org/10.1109/TTS.2024.3432407.

Trček, Denis. “Cultural Heritage Preservation by Using Blockchain Technologies.” Heritage Science 10, no. 1 (January 10, 2022): 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40494-021-00643-9.

UNESCO Media. “List of Factors Affecting the Properties.” Reporting & Monitoring. UNESCO World Heritage Convention. Accessed April 3, 2025. https://whc.unesco.org/en/factors/.

Wang, Xudong, Yanwu Wang, Qinglin Guo, Qiangqiang Pei, and Guojing Zhao. “The History of Rescuing Reinforcement and the Preliminary Study of Preventive Protection System for the Cliff of Mogao Grottoes in Dunhuang, China.” Heritage Science 9, no. 1 (May 27, 2021): 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40494-021-00537-w.

Wang, Yihui, and Xiaodong Wu. “Current Progress on Murals: Distribution, Conservation and Utilization.” Heritage Science 11, no. 1 (March 27, 2023): 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40494-023-00904-9.

Xing, Yongkang, Yi Xiao, and Yongjie Luo. “Integrating Restoration and Interactive Exploration to Enhance Cultural Heritage through VR Storytelling.” Scientific Reports 14, no. 1 (September 11, 2024): 21194. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-72182-9.

Xu, Hui, Yonghua Zhang, and Jiawan Zhang. “Frescoes Restoration via Virtual-Real Fusion: Method and Practice.” Journal of Cultural Heritage 66 (March 1, 2024): 68–75. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.culher.2023.11.001.

Yang, Su, Miaole Hou, and Hongchao Fan. “CityGML Grotto ADE for Modelling Niches in 3D with Semantic Information.” Heritage Science 12, no. 1 (May 1, 2024): 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40494-024-01260-y.

Yanxiang, Zhang, Ding Min, Zhu Ziqiang, Sui Dan, and Fangbemi Abassin. “Painting Based Cubic VR Also for CAVE and Spherical Screen Film.” In 2013 International Conference on Culture and Computing, 139–40, 2013. https://doi.org/10.1109/CultureComputing.2013.35.

Yu, Tianxiu, Cong Lin, Shijie Zhang, Chunxue Wang, Xiaohong Ding, Huili An, Xiaoxiang Liu, et al. “Artificial Intelligence for Dunhuang Cultural Heritage Protection: The Project and the Dataset.” International Journal of Computer Vision 130, no. 11 (November 2022): 2646–73. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11263-022-01665-x.

Zhan, Jiawei, Yu Meng, Longqing Zhang, Kangshun Li, and Fengting Yan. “Research on Computer Vision in Intelligent Damage Monitoring of Heritage Conservation: The Case of Yungang Cave Paintings.” Npj Heritage Science 13, no. 1 (March 1, 2025): 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1038/s40494-025-01567-4.

Zhao, Fanhua, Hui Ren, Ke Sun, and Xian Zhu. “GAN-Based Heterogeneous Network for Ancient Mural Restoration.” Heritage Science 12, no. 1 (December 5, 2024): 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40494-024-01517-6.

Zhu, Jun-Yan, Taesung Park, Phillip Isola, and Alexei A. Efros. “Unpaired Image-to-Image Translation Using Cycle-Consistent Adversarial Networks.” arXiv, August 24, 2020. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1703.10593.