To read the author’s full research report on linguistic equity in the arts sector, click here.

INTRODUCTION

The first installment of this article series argued that linguistic representation and accessibility are key to the development of an artistic sector in which diverse individuals and communities can engage with art in order to strengthen their own identities and, in turn, “understand how [they] matter.” Unfortunately, the United States’ artistic sector currently fails to appropriately address the significant cultural and linguistic diversity of the nation’s resident population. This does not mean, however, that there is an exhaustive lack of artistic organizations that institute best practices in linguistic diversity and accessibility to strengthen their missions.

In the second installment of this article series, Deaf West Theatre’s 2015 Broadway revival of Spring Awakening proved that (1) language and linguistic identity can advance and strengthen artistic storytelling and (2) audiences want to see linguistically diverse and accessible stories. Further, in this series’ third installment, Opera Australia showed that (1) the preservation of original languages in art does not have to deter audiences from engagement and (2) linguistically diverse work is not inherently elitist and inaccessible.

The present article looks at best practices for the propagation of creative linguistic diversity in film and television, and how technology-driven digital and translation technologies can strengthen accessibility in the field. The success of Netflix’s streaming service and business model suggests that (1) the inclusion of linguistically diverse stories promotes otherwise unseen opportunities for international growth and (2) multilingual entertainment invites unprecedented international connectedness by the promotion of shared themes, ideals, and fashions.

AN OVERVIEW OF NETFLIX’S LANGUAGE PRACTICES

Image I: Netflix’s online launch page circa mid-2004 (Product Habits Blog)

Netflix is the most popular film and television streaming platform in the United States. Conceived in 1997 by entrepreneurs Reed Hastings and Marc Rudolph, Netflix was initially launched as an online, mail-order subscription service. In 2007 the platform began offering digital streaming alongside the pre-existing mail-order rentals, and in 2010 expanded to subscription packages exclusively including Internet-based streaming. Political thriller House of Cards ushered in the early stages of Netflix’s empire of programming made exclusively for the platform, winning three Primetime Emmy Awards in the 2013 season. As of August 2022, just over half of Netflix’s library of films, documentaries, and episodes of television available in the United States were Netflix Originals. In fact, as of January 2023 the streaming service’s top 5 most watched films (Red Notice, Don’t Look Up, Bird Box, The Gray Man, and Glass Onion) and individual seasons of television series (Squid Game, Stranger Things, Wednesday, Dahmer, and Money Heist) were indeed Netflix originals. It is the joint success of Netflix’s relatively early transition to online streaming and the development of a vast network of original works that has allowed Netflix to thrive in over 190 countries and territories less than 30 years after its inception.

Video I: Promotional video published on January 18, 2023 highlighting Netflix Originals coming in 2023 (Netflix)

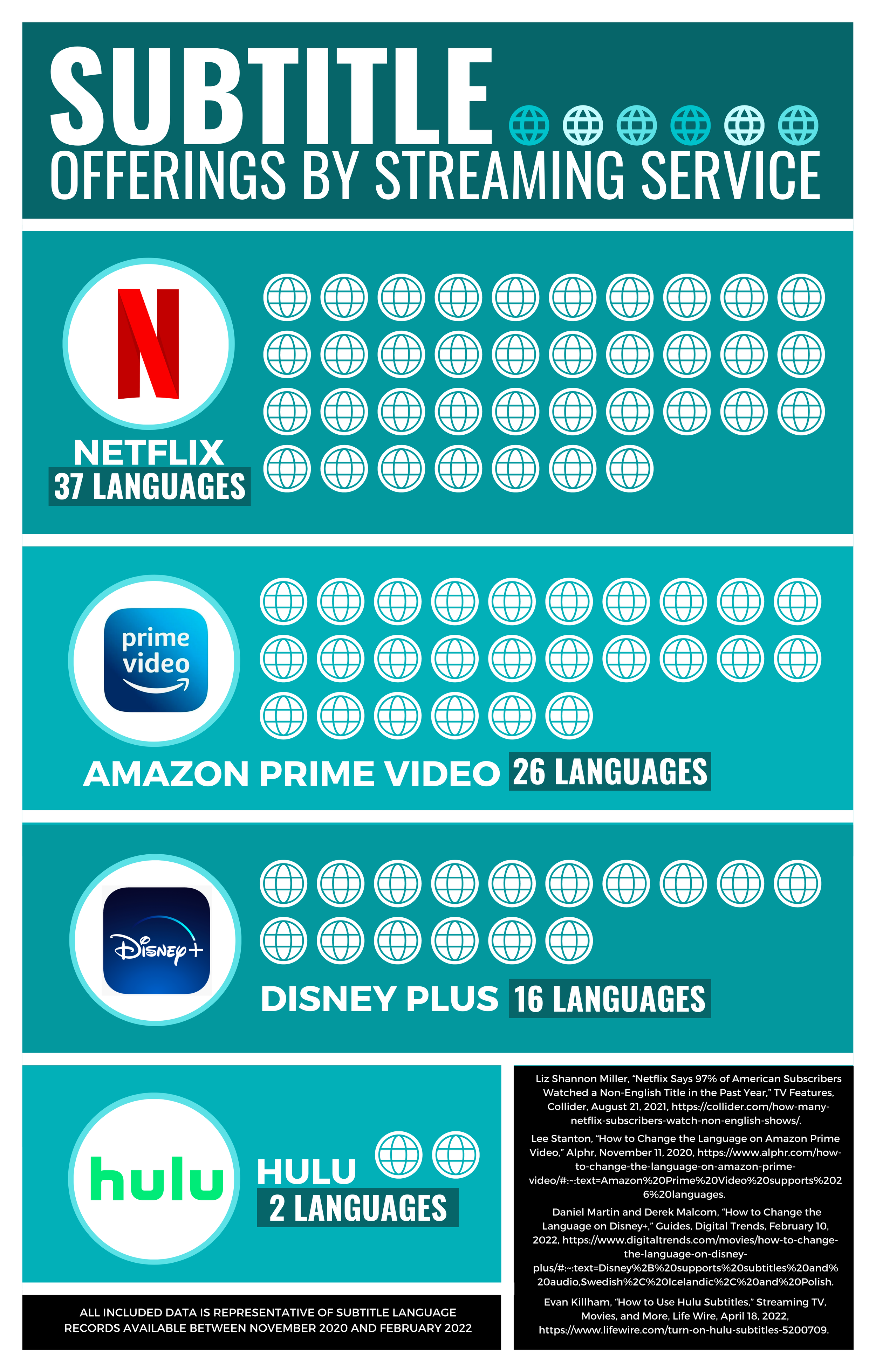

Central to Netflix’s growth is the company’s keen understanding of its diverse, international markets. As exhaustively established in this article’s predecessors, a comprehension of a population’s language-driven-identities is paramount in the comprehension of their larger national cultures. It is no surprise, then, that international subscribers “often prefer local-language programming” and the 1 in 5 United States residents who speak a language other than English would seek out non-English works. To this end, as of 2019 non-English media made up 45% of Netflix’s total streaming content and 35% of Netflix Originals available in the United States. Further, as of mid-2021 the service provides dubbing in 34 languages, subtitles in up to 37 languages, and investment in dubbing increasing by a factor of 25 to 35 percent annually as of 2019 reports. This is especially impressive when compared to Amazon Prime’s supported 26 subtitle languages, Disney Plus’s 16, and Hulu’s two (English and, occasionally, Spanish) during the similar time frame. Netflix’s commitment to the language-based identities of its diverse consumer base as a central tool in their globalization strategies are readily evident through the mass expansion of their non-English programming and language accessibility technologies.

Figure I: Overview of subtitle languages available on Netflix, Hulu, Disney Plus, and Amazon Prime Video based on publicly accessible information from November 2020 to February 2022. (Figure by Author)

““Between August 2020 and August 2021 a staggering 97 percent of United States Netflix subscribers consumed a non-English title.””

Importantly, it is not only non-English speakers who take advantage of Netflix’s multilingual offerings. In a report from Collider, between August 2020 and August 2021 a staggering 97 percent of United States Netflix subscribers consumed a non-English title. This statistic represents a 71 percent increase in non-English viewing in just two years. Evidently, Netflix does not produce and acquire non-English media simply for the sake of linguistically diversifying their catalog. Rather, they aim to support works genuinely in line with their mission statement of “entertain[ing] the world” where “whatever [one’s] taste, and no matter where [one lives, they are given] access to best-in-class TV series, documentaries, feature films, and mobile games.” Though there is always room for improvement (which will be discussed in length later in this report), Netflix exudes best practice in linguistic representation in the artistic and entertainment sectors.

“To Netflix, English is a language of entertainment, not the language of entertainment. ”

Access to linguistically diverse stories helps individuals “understand how [they] matter.” Further, popular media holds the power to “tell [a] society who and what is important.” Netflix’s self-proclaimed “best-in-class,” multilingual, highly-popular programming champions diverse languages and cultures in such a way that (1) non-English speakers can use the media representation of their language to strengthen their identities and (2) diverse populations come to understand the value of and opportunities contained within languages besides their native tongue. Put another way, to Netflix, English is a language of entertainment, not the language of entertainment. In addition to creating a route for the platform to globalize and rapidly grow revenue, this perspective allows for the seamless integration of linguistic diversity into programming, which invites routes for international growth in terms of both accessibility as well as shared culture.

SQUID GAME AND THE INTERNATIONAL LANGUAGE MARKET

In recent years, in addition to more culturally niche works aimed at the populations belonging to individual non-American cultures, Netflix’s multilingual growth has massively capitalized on the development of stories and themes that capture mass global consumer appeal, blind to their language of presentation. Netflix Original series Money Heist (Spanish), All of Us Are Dead (Korean), Lupin (French), and Narcos (Spanish / English) have garnered millions of views each in the United States, and Original films including Roma (Spanish) and The Hand of God (Italian) have received mass critical appeal. However, in the most striking example to-date the 2021 release of Hwang Dong-hyuk’s Korean series Squid Game unquestionably proved the viability of cross-cultural entertainment appeal in languages other than English.

Video II: Official Squid Game trailer (Netflix)

The series’ nine-episode first season was described by Vulture as “a thrilling and dark indictment of capitalism and class disparity” in which 456 financially desperate South Korean adults compete in a series of brutally adapted children’s games in order to win $45.6 billion won. According to Forbes, key to Squid Game’s storytelling success was the fact that it “manages to reflect the feeling of the present moment, in the same way the decrepit, deceitful rulers of Game of Thrones reflected audience’s apathy and anger toward the political process[es of the world].” Unsurprisingly, this cross-culturally relevant thematic formula had worked before for international audiences, with South Korean films Train to Busan and Parasite’s class-centered narratives garnering popular and critical traction across the world. Despite this precedent, however, Squid Game’s success exceeded all expectations.

“Exactly two months after the show’s release, Netflix users had collectively streamed Squid Game for 2.1 billion hours (or, 239,700 years)”

Just under two weeks after its September 17, 2021 premiere, Squid Game was labeled the most popular show in 90 of Netflix’s 190 streaming countries. Further, an analysis of its combined Netflix streams, Google searches, and recorded illegal downloads led Parrot Analytics to deem the program “a word-of-mouth global sensation” and “the most in-demand show in the world” less than a month after its release. Netflix’s global TV head Bela Bajaria had expected success from Squid Game due to the fact that Netflix users’ K-drama (Korean drama) consumption in the United States had increased by a factor of 200 percent between September 2019 and September 2021, yet they “could not imagine that it would [get] this big globally.” Of course, the show only continued to grow in popularity. Exactly two months after the show’s release, Netflix users had collectively streamed Squid Game for 2.1 billion hours (or, 239,700 years)– making the dark thriller the streaming service’s most popular show to date, and remains the most watched by hour as of January 2023.

Image II: Creator, writer, director, and producer Hwang Dong-hyuk on the set of Squid Game’s third episode (Variety)

Yet, the rapid success of Squid Game upon its release massively contradicted its road to production. Though originally conceived as a feature film, Squid Game’s creator, writer, director, and producer Hwang Dong-hyuk came up with the series’ plot in 2008, and developed a completed script by 2009. However, in 2009 Hwang commented that producers found the story too “bizarre,” and took over a decade to eventually be picked up by Netflix. In Hwang’s eyes, “after about 12 years, the world [had] changed into a place where such peculiar, violent, survival stories are actually welcomed. People commented on how the series is relevant to real life. Sadly, the world has changed in that direction.” Key to Squid Game’s eventual green-lit production as well as its rapid global success was, once again, its thematic commitment to inter-continental realities that garnered empathy and interest from dozens of culturally distinct people groups: economic inequality, capitalist society, and humanitarian trauma. With Squid Game, Netflix and Hwang used art and entertainment as a tool to connect cultures through a shared understanding of deeply-human themes in an international language market.

TRANSLATION TECHNOLOGY, ACCESSIBILITY, AND ACCURACY

In addition to the proven worldwide potential for non-English, internationally relevant entertainment on a global scale, Squid Game’s popularity invited novel conversations on translation and accessibility technologies. To begin, it is important to distinguish between captions and subtitles. While they both are used as accessibility technologies for those who are unable to access certain pieces of media, captions are a projected “text version of the spoken part of a television, movie, or computer presentation” that are “in the language of the medium rather than a translation to another language.” On the other hand, subtitles are projected translations most commonly “for people who don’t speak the language of the medium.” To this end, by definition, subtitles do not necessitate direct translation.

Figure II: The differentiation between subtitles and captions (Image via Author)

““Subtitles have a capacity to generate their own modes of representation and interpretation and to sensitize audiences linguistic and cultural differences.””

In fact, linguist Marie-Noëlle Guillot posits that “subtitles have a capacity to generate their own modes of representation and interpretation and to sensitize audiences linguistic and cultural differences,” a capacity that “tends to be obscured in face-value textual comparison routinely highlighting ‘loss’ in translation.” In other words, translation-based alterations in subtitling practices hold the power to better expose widespread people groups to linguistic and cultural differences–inviting the all-important understandings of why other cultures “matter.” Regardless, even when positively implemented for cultural gain, these positive linguistic changes are often a target for criticism as a “loss” or mistake. Where subtitles walk a dangerous line, however, is between making these positive translation alterations for the sake of cultural understanding and going too far to such an extent that the content suffers. In fact, it is a perceived “loss” of the South Korean language while watching with English closed captions that sparked Squid Game’s translation controversy.

On September 30, 2021, Korean speaker Youngmi Mayer tweeted: "not to sound snobby but I'm fluent in Korean and I watched Squid Game with English subtitles and if you don't understand Korean you didn't really watch the same show." In one example, Mayer pointed out that the manipulative Han Mi-nyeo (Kim Joo-Ryoung) is quoted as saying “I’m not a genius, but I can work it out,” when the direct Korean translation is “I am very smart, I just never got a chance to study.” This line’s shifted meaning prevents non-Korean speakers from grasping a key element of Mi-nyeo’s character, struggle, and motivations in the game. However, there was a deeper reality to these “botched” translations. Rather than watching Squid Game with subtitles (“English”), Mayer was watching with English closed captions (“English [CC]”): a translation of the English dubbed version of the show. Upon investigation, using English subtitles, Mi-nyeo says: “I never bothered to study, but I am unbelievably smart,” a much more accurate translation of the original meaning. The almost unassuming switch from one English translation to another transforms how individuals could interface with Squid Game and its characters.

Figure III: Illustration of three translation manifestations in Netflix’s Squid Game

(image via Author)

““The ‘untranslatable’ exists in all cultures” and “a meaning gap inevitably exists between the original Korean and the English subtitles due to the untranslatable.” ”

Even so, of course, the translation is not exact, which raises a fascinating question of the extent to which multilingual services such as Netflix can ensure the accuracy of their captions, subtitles, and other language accessibility features. As stated above, Netflix is a standout in the world of language accessibility for offering dubbing in 34 languages and subtitles in up to 37 languages. However, this does not mean that the service has necessarily mastered walking the line between positive, culturally motivated translations and “botched” misunderstandings. Of the Squid Game captioning vs. subtitles debacle, English-Korean interpreter Jinhyun Cho wrote: “subtitling becomes even more complicated when cultural factors come into play, because many culture-specific words and concepts are difficult to translate.” In her words, “the ‘untranslatable’ exists in all cultures” and “a meaning gap inevitably exists between the original Korean and the English subtitles due to the untranslatable.”

An example of such in Squid Game is the use of age-based honorifics used by South Koreans in conversation for which there is no equivalent English form, and as such some of the emotional weight tied to shifts in how characters refer to each other is inevitably lost for non-Korean speakers regardless of the manner in which the series is translated into English. Instead of relying on subtitles as the only “cultural and linguistic bridge” through which one may understand the “untranslatable” elements inevitable in non-English works, Cho writes that this gap “can only be filled by genuine understanding of the other culture and language.” Subtitles and captioning are just the first step in bridging linguistic divides, and as such it is up to individuals and production companies to further the development of cross-cultural understanding through the entertainment they both consume and produce.

“The gap caused by what is “untranslatable” can “only be filled by genuine understanding of the other culture and language.”

While it appears impossible for services such as Netflix to fully overcome the “untranslatable,” this is not to say that their translation and linguistic accessibility technology needs no improvement. Strings of recent linguistic research have focused heavily on opportunities for dynamic subtitles (“placing subtitles in varying positions, according to the underlying video content”) to increase consumer engagement and comprehension. Researchers reporting at the 2015 ACM International Conference explained that there is an opportunity for dynamic subtitles to make the “overall viewing experience less disjointed and more immersive” for a proportion of viewers. Following the study, “the majority of people who watched dynamic subtitles enjoyed the experience and wanted to try them further” largely due to the fact that they were able to be more engaged in the action of the media and “pick up more non-verbal cues from actors” as subtitles were not permanently fixed at the bottom of the screen. One participant reported: “I wouldn’t have caught a lot of the small social cues if I were watching this with traditional subtitles.” However, concerns were raised by those who questioned whether the dynamic subtitles would be too distracting for those who did not need them. As such, I posit that Netflix can continue to exude best practice in translation and accessibility technologies through testing and implementing an additional dynamic subtitling option for streaming content.

Image III: “Red Light, Green Light” doll from Netflix’s Squid Game (Variety)

WHAT NETFLIX MEANS FOR THE ARTS SECTOR

Netflix possesses an explicit understanding of the value of international markets in the growth of their business model, and as such prioritizes multilingualism as a tool for globalization. The success of Netflix’s non-English programming and industry-best translation technologies both in the United States and globally supports the viability of linguistic diversity from a cultural and capital perspective. While unique in their global scale and nature as a for-profit corporation as compared to most United States artistic organizations, the lessons taught by Netflix’s language-driven globalization and commitment to language-based-identity are highly applicable to the larger creative sector as a whole.

(1) The inclusion of linguistically diverse stories promotes otherwise unseen opportunities for international growth.

As explored above, Netflix’s transition to online streaming and the development of highly popular original works was what allowed the company to launch its network to over 190 countries and territories. However, it is its commitment to “best-in-class” linguistically diverse stories that has allowed it to stay and thrive in these regions. Importantly, it is not just native speakers of a particular language who take advantage of Netflix’s linguistically diverse offerings; between August 2020 and August 2021 a staggering 97 percent of United States Netflix subscribers consumed a non-English title and Korean thriller Squid Game remains the platform’s most popular show as of January 2021. Linguistic diversity for the sake of genuinely good media rather than for the sake of “checking a diversity box” has allowed both the platform and its multilingual catalog to reach massive global audiences. Most importantly, this growth and access to diverse stories both helps individuals “understand how [they] matter” and creates routes through which diverse populations can come to understand the value of cultures that exist beyond their native tongues.

(2) Multilingual entertainment invites unprecedented international connectedness by the promotion of shared themes, ideals, and fashions.

The unequivocal success of Hwang Dong-hyuk’s Squid Game was largely ushered in by the thematic global applicability of its story. Economic inequality, capitalist society, and humanitarian trauma are realities accessible to a large proportion of the world, and empathy and interest garnered by these realities made the show a global success. Of course, Squid Game’s record breaking streaming performance was largely aided by the strength of Netflix’s presence on a global scale, but it was Netflix’s commitment to producing a story with thematic promise for multilingual connectedness that made the work stand out internationally. In this sense, Squid Game offers a path towards international connectivity and linguistic diversity through the artistic depiction of individual culture framed by what is shared between diverse cultures.

-

Adalian, Josef. “Planet ‘Squid Game’.” Buffering. Vulture. September 30, 2021. https://www.vulture.com/article/planet-squid-game-netflix-biggest-show.html.

Ankers-Range, Adele. “Squid Game Has Multiple English Translation and One is Seemingly More Accurate Than the Other.” Squid Game. IGN. Updated October 4, 2021. https://www.ign.com/articles/squid-game-netflix-english-language-translations-accuracy.

Bamsey, Amelia. “Squid Game’s Mesmerizing Staircase Has An Equally Trippy Origin Story.” Art. Creative Bloq. October 5, 2021. https://www.creativebloq.com/news/squid-game-aesthetic.

Bisson, Marie-Josée et al. “Processing of Native and Foreign Language Subtitles in Films: An Eye Tracking Study.” Applied Psycholinguistics 35, no. 2 (March 2014): 399–418. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0142716412000434.

Brennan, Louis. “How Netflix Expanded to 190 Countries in 7 Years.” Global Strategy. Harvard Business Review. October 12, 2018. https://hbr.org/2018/10/how-netflix-expanded-to-190-countries-in-7-years.

Brown, Andy et al. “Dynamic Subtitles: The User Experience” in Proceedings of the ACM International Conference on Interactive Experiences for TV and Online Video (TVX’15:ACM International Conference on Interactive Experiences for TV and Online Video, Brussels Belgium: ACM, 2015). 103–112. https://doi.org/10.1145/2745197.2745204.

“Captions and Subtitles.” Captions. UCL. Accessed January 12, 2023. https://www.ucl.ac.uk/mediacentral/captions/captions-or-subtitles-whats-difference.

Castellini, Bri. “Why Representation Matters.” Pipeline Artists. February 9, 2021. https://pipelineartists.com/why-representation-matters-in-arts/.

Cho, Jinhyun. “‘Squid Game’ and the Untranslatable: The Debate Around Subtitles Explained.” Arts + Culture. The Conversation. October 13, 2021. https://theconversation.com/squid-game-and-the-untranslatable-the-debate-around-subtitles-explained-169931.

Clark, Travis. “'Game of Thrones' is Still One of the World's Most Popular Series, Data Shows, as HBO Readies Spinoffs Including a New Sequel About Jon Snow.” Media. Insider. June 27, 2022. https://www.businessinsider.com/game-of-thrones-still-one-of-worlds-biggest-shows-data-2022-6.

Descombes, James. “Oscar Nominations on Netflix 2022: From The Power of the Dog to Tick, Tick… BOOM! – Oscar-Nominated Films and Documentaries to Stream on Netflix.” Film. BT. February 8, 2022. https://www.bt.com/tv/film/oscar-nominated-movies-films-documentaries-netflix-winners.

Dietrich, Sandy and Erik Hernandez. “Language Use in the United States: 2019.” United States Census Bureau. September 1, 2022. https://www.census.gov/library/publications/2022/acs/acs-50.html.

Di Placido, Dani. “The Secret to the Success of ‘Squid Game,’ Explained.” Arts. Forbes. October 6, 2021. https://www.forbes.com/sites/danidiplacido/2021/10/06/the-secret-to-squid-games-success-explained/?sh=3cf15005224c.

Guillot, Marie-Noëlle. “Film Subtitles and the Conundrum of Linguistic and Cultural Representation” in Contrastive Media Analysis. ed. Stefan Hauser, Martin Luginbuhl, Martin Luginbühl (Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing Company, 2012), 101 - 121.

Guillot, Marie-Noëlle. “Stylisation and Representation in Subtitles: Can Less Be More?.”Perspectives: Studies in Translatology 20, no. 4 (December 2012): 479–94. https://ueaeprints.uea.ac.uk/id/eprint/40496/1/Stylization_and_representation_in_subtitles_can_less_be_more.pdf.

Gyu-lee, Lee. “INTERVIEW: Director Shares Backstory of Global Hit ‘Squid Game’.” Entertainment & Arts. The Korea Times. September 30, 2021. https://www.koreatimes.co.kr/www/art/2021/09/398_316211.html.

Hosch, William.“Netflix: American Company.” Movies. Britannica. Accessed January 11, 2023. https://www.britannica.com/topic/Netflix-Inc.

“How Netflix Became a $100 Billion Company in 20 Years.” Product Habits Blog. Accessed January 28, 2023. https://producthabits.com/how-netflix-became-a-100-billion-company-in-20-years/.

Keslassy, Elsa. “‘Squid Game’ Director Hwang Dong-hyuk Prepares ‘Killing Old People Club’ as Next Feature.” Global. Variety. April 4, 2022. https://variety.com/2022/film/global/squid-game-hwang-dong-hyuk-killing-old-people-club-1235222839/.

Killham, Evan. “How to Use Hulu Subtitles.” Streaming TV, Movies, and More. Life Wire. April 18, 2022. https://www.lifewire.com/turn-on-hulu-subtitles-5200709.

Khan, Aamina. “There’s a Reason Squid Game’s Subtitles Aren’t Perfect.” The Cut. October 7, 2021. https://www.thecut.com/2021/10/squid-games-subtitles-arent-perfect-for-a-reason.html.

Martin, Daniel and Derek Malcom. “How to Change the Language on Disney+.” Guides. Digital Trends. February 10, 2022. https://www.digitaltrends.com/movies/how-to-change-the-language-on-disney-plus/#:~:text=Disney%2B%20supports%20subtitles%20and%20audio,Swedish%2C%20 Icelandic%2C%20and%20 Polish.

Mayer, Yongmi. Twitter Post. September 30, 2021. 10:36 AM. https://twitter.com/ymmayer/status/1443615642385592324.

Miller, Liz Shannon. “Netflix Says 97% of American Subscribers Watched a Non-English Title in the Past Year.” TV Features. Collider. August 21, 2021. https://collider.com/how-many-netflix-subscribers-watch-non-english-shows/.

Moore, Kasey. “Does Netflix Have Too Much Foreign Content?.” Netflix News. What’s on Netflix. August 5, 2020. https://www.whats-on-netflix.com/news/does-netflix-have-too-much-foreign-content/.

Moore, Kasey. “Netflix Originals Now Make Up 50% of Overall US Library.” Netflix News. What’s On Netflix. August 24, 2022. https://www.whats-on-netflix.com/news/50-of-netflixs-library-is-now-made-of-netflix-originals/.

“Most Popular Non-English Language Netflix TV Shows of All Time as of October 2022, by Number of Hours Viewed.” TV, Video, and Film. Statista. October 19, 2022. https://www.statista.com/statistics/1281584/most-viewed-netflix-show-non-english/.

NEA Staff. “Why the Arts Matter.” National Endowment for the Arts. September 23, 2015. https://www.arts.gov/stories/blog/2015/why-arts-matter.

Roxborough, Scott. “Netflix’s Global Reach Sparks Dubbing Revolution: ‘The Public Demands It.’” TV News. The Hollywood Reporter. August 13, 2019. https://www.hollywoodreporter.com/tv/tv-news/netflix-s-global-reach-sparks-dubbing-revolution-public-demands-it-1229761/.

“Save the Dates | 2023 Films Preview | Official Trailer | Netflix.” YouTube Video. 2:38. Posted by “Netflix.” January 18, 2023. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=brTcuO49G4I.

Shepherd, Jack. “You Could Be Watching ‘Squid Game’ Wrong- All Because of a Netflix Error.” Drama. Total Film. Updated October 4, 2021. https://www.gamesradar.com/squid-game-translation-english-korean-closed-caption/.

Stanton, Lee. “How to Change the Language on Amazon Prime Video.” Alphr. November 11, 2020. https://www.alphr.com/how-to-change-the-language-on-amazon-prime-video/#:~:text=Amazon%20Prime%20Video%20 supports%2026%20 languages.

Stoll, Julia. “Share of Households Subscribing to Selected Video Streaming Platforms in the United States as of September 2022.” TV, Video, and Film. Statista. November 3, 2022. https://www.statista.com/statistics/274192/streaming-services-penetration-rates-in-the-us/#:~:text=Netflix%20is%20unsurprisingly%20the%20most,platform%20in%20the%20United%20States.

Solsman, Joan. “Netflix's Squid Game Was Even Bigger Than You Thought -- 2.1B Hours Big.” Entertainment. CNET. November 17, 2021. https://www.cnet.com/culture/entertainment/netflix-squid-game-is-even-bigger-than-you-thought-2-billion-hours-big/.

Solsman, Joan. “Netflix’s Top Hit Shows and Movies, Ranked (According to Netflix).” Services & Software. CNET. January 10, 2023. https://www.cnet.com/tech/services-and-software/netflixs-top-hit-shows-and-movies-ranked-according-to-netflix/.

“Squid Game.” TV. Vulture. Accessed January 12, 2023. https://www.vulture.com/tv/squid-game/.

“Squid Game | Official Trailer | Netflix.” YouTube video. Posted by “Netflix.” September 1, 2021. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oqxAJKy0ii4.

“The Story of Netflix.” Netflix. Accessed January 11, 2023. https://about.netflix.com/en.

Zandt, Florian. “Squid Game Becomes Netflix’s New Number 001.” Statista. October 13, 2021. https://www.statista.com/chart/25957/most-watched-netflix-shows-in-first-28-days-since-release/.