To read the author’s full research report on linguistic equity in the arts sector, click here.

INTRODUCTION

In the first installment of this article series, it was argued that linguistic representation and accessibility are key to the development of a genuinely inclusive artistic sector in which diverse communities can use art to strengthen their own identities and “understand how [they] matter.” However, the United States’ artistic sector currently fails to appropriately represent the cultural and linguistic diversity of its artistic constituents. Of course, this does not mean that there are no artistic organizations who use questions of linguistic identity and accessibility to further their missions and programming.

In the first of three case studies in this article series, Deaf West Theatre’s 2015 revival of Spring Awakening proved that (1) language and linguistic identity can advance and strengthen artistic storytelling and (2) audiences want to see linguistically diverse and accessible stories.

The following case looks at best practices for the maintenance of linguistic diversity in opera, and how technology can be used to reenergize the historic genre for a contemporary audience. Ultimately, Opera Australia teaches that (1) the preservation of original languages in art does not have to deter audiences from engagement and (2) linguistically diverse work is not inherently elitist and inaccessible.

OPERA IN THE UNITED STATES

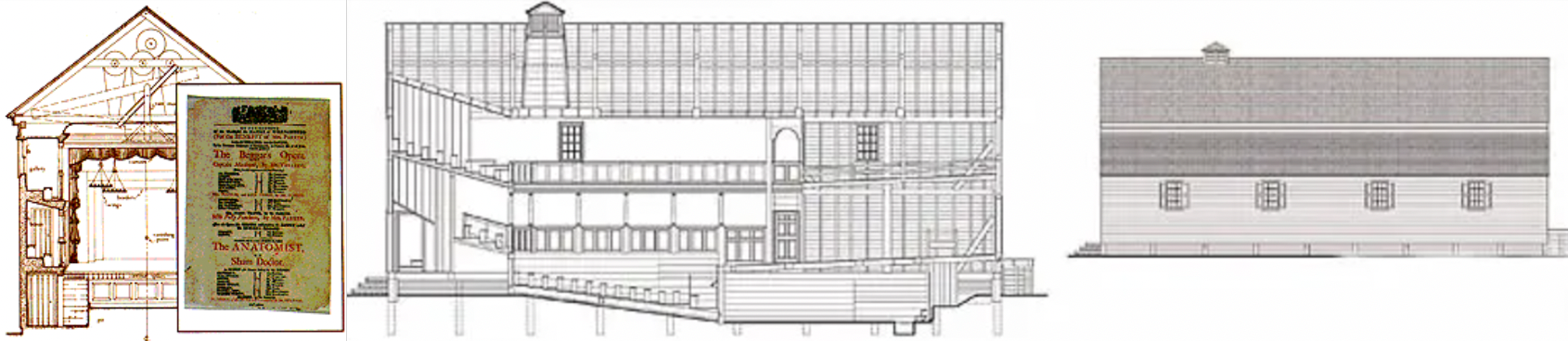

Dated to 1722, the first American opera house (named, “The Playhouse”) is believed to have been constructed in Williamsburg, Virginia– which served as the nation’s capital between 1699 and 1780. A majority of performers in the first half of the eighteenth century were from England, and performed translated works from Italy and Germany. However, for many culturally blooming cities such as Williamsburg at the start of the eighteenth century, opera performances were strongly opposed by a rapidly developing, politically strong network of religious groups. By 1774, the performance of opera–as well as other luxuries such as gambling and more general theatre–were declared “unpatriotic and unacceptable” by the nation’s Continental Congress, and banned across all 13 colonies.

Image 2: Plans for the reconstruction of Williamsburg, Virginia’s “Playhouse” (The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation and The New York Times)

By the end of the Revolution, there were “scattered attempts” for Americans to compose and perform opera, but they were met with little success by critics and consumers alike– deemed “pale imitations of European models.” However, in the years following the American Civil War (1861 - 1865), opera houses became a commodity for cities big and small. As explained by the New England Historical Society, “an opera house provided a sense of urbanity and many small communities used them as an enticement for the railroad companies to establish stops near their villages.” Jumping to the 1920s and 1930s, American artists trained in Europe once again attempted to create a distinctively American form of opera, yet—due to the genre’s history—the general public continued to see “it as elitist, unrealistic, and irrelevant.” In the United States, then, truly “distinctive” American opera never found its niche in general cultural interests. However, the cultural, or “elite” status of European-language opera made opera houses and select non-English operatic productions a staple of sophisticated or elite culture for the nation. In fact, contemporary United States opera companies rely almost exclusively on pieces written between the late-eighteenth and early-twentieth centuries for their standard repertoires.

Into modern day, the five most performed operas internationally are in German, Italian, and French. The United States is the second highest producer of opera by performances globally, of which 19 percent are performed in New York City. However, the National Endowment for the Arts reports that in 2017, for those who engaged with cultural or artistic programming, the lowest proportion attended an opera. Further, opera attendance decreased by a factor of 25 percent between 2012 and 2017. In 2017 as a whole, only 2 percent of the United States adult population attended a live opera. This statistic is staggering when compared to the 24 percent that attended a live play or musical.

Since its introduction in the United States, the central setback to Americans' lack of engagement with opera is twofold. First, consumers claim an inability “to follow [stories] in a different language.” Next, Americans express that opera is “too expensive” or inaccessible for the average consumer. As Jerome Socolof wrote for American’s for the Arts in summation of his early conceptions of opera: “it’s a bunch of people in horns singing in languages I don’t understand for longer than I want to listen.” Inaccessibility both in terms of the genre’s constructed elitism and perceived language barriers is what has led certain opera professionals to question if “millennials will kill opera” and if the art form will die out in the foreseeable future.

Contrary to these struggles, however, if opera has proved anything in its over 400-year history, it is that the art form can stand the test of time. Where the American artistic sector largely falls short is in how to produce opera both by and for modern audiences while overcoming the genre’s reemerged association with the elite. The preservation of linguistic diversity and culture are key to the celebration of opera and its rich history.

In turn, extensive language-based technology is necessitated to facilitate culturally and historically meaningful iterations of centuries-old art that are accessible and understandable to widespread audiences. In addition to this maintenance of linguistic history, however, American artists must come to terms with the “elitism” of the genre throughout time. When arts in the United States fail to find the intersection of language-based equity and modern applicability, the death of opera in the nation is practically inevitable. Luckily, there are several companies across the world that are already acting upon best practices for the maintenance of linguistic diversity alongside reenergized operatic style, largely through the use of cutting-edge technology. An analysis of these organizations can offer guidance to a United States artistic sector in need of new life for the centuries-old genre.

opera Australia: RECONSTRUCTED OPERATIC STYLE for all

Opera Australia’s mission is to “perform some of the greatest music ever written to as many people as possible.” In a similar vein, their vision is to enrich “Australia’s cultural life with exceptional opera.” Since its inception in 1956, core to Opera Australia’s operations has been this commitment to opera for everyone: dedicating themselves and their programming to a purposeful separation from the “elitist” atmosphere that still plagues much of European and American opera. Offering a complex repertoire of annual performances, the Company’s dual home is the Sydney opera House and Arts Centre Melbourne, but promotes touring productions in local theaters and public spaces across the continent. Every year, Opera Australia tours and performs for over 80,000 primary school children and offers discounted tickets and educational materials for students and educators of all ages. The Company’s outreach programs “work to transcend barriers so that no matter where you live or your economic or social status students get to experience, engage and delight in music and opera.” To break down barriers of accessibility and “elitism,” Opera Australia’s seasons offer a unique blend of English-language musicals and concerts alongside their full-length opera season. The company and its outreach programs position Opera Australia as arts and culture made for all ages, income brackets, and experience levels.

Actualizing progress in their vision to “enrich Australia’s cultural life,” Opera Australia reaches thousands of diverse consumers annually. Further, language and “elitism” do not appear as barriers to Company performance. To illustrate, of Opera Australia’s 17,350 national tour attendees in 2021, 46 percent reported that it was their first time experiencing an opera and 94 percent reported that they would attend an Opera Australia production again in the future. Further, of these audiences while only 23 percent identified themselves as being from linguistically diverse, non-English-speaking backgrounds, 94 percent reported that they “enjoyed” the Opera being performed in French–its original language of composition. Especially in their first year of operation following the outbreak of Covid-19, these numbers are staggering.

ACCESSIBILITY PRACTICES & DIGITIZATION AT OPERA AUSTRALIA

Key to Opera Australia’s success is a complex network of accessibility measures. It is the attention paid to these accessibility practices that make consumers break free of their assumptions of opera’s “elitism” and language-based inaccessibility. As Opera Australia’s Chief Executive Rory Jeffes posits, “we’re already a fifth of the way through the twenty-first century, so it’s high time we kept up with audiences who are now dealing with digital in their everyday life.” In addition to efforts to use technology and “digitized” opera to make the field more accessible to modern audiences, Opera Australia recognizes that “digital is part of our future, not the future.” An understanding of digitization as a tool to promote accessibility both in terms of language and public interest, Opera Australia uses an integration of large production screens in order to reduce the turnaround time between productions and in turn “program a greater variety of operas, [still] including purist-pleasing ones with traditional [, non-screen-reliant] staging” and new, Australia-born works.

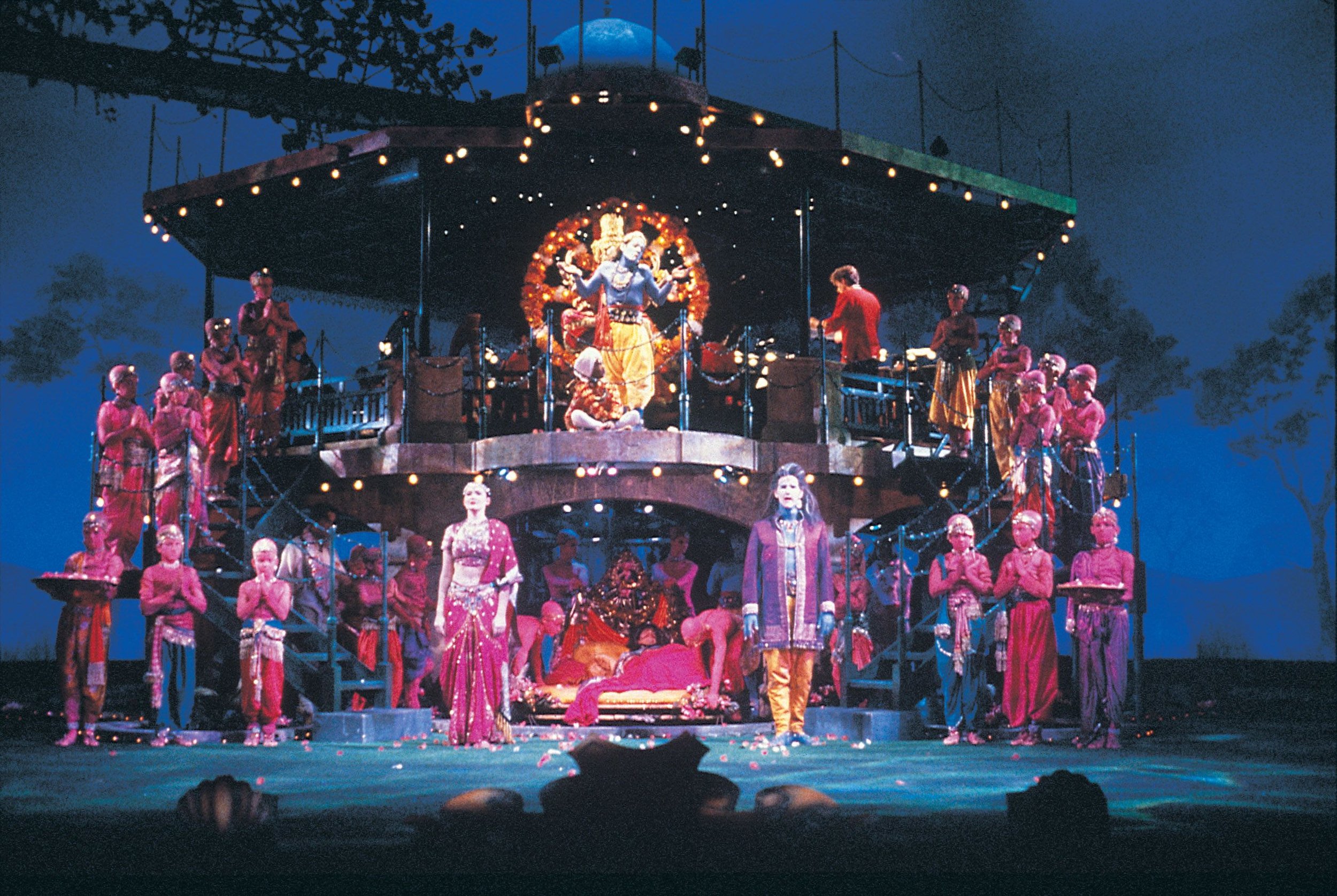

Image 3: Physical scenic elements against a backdrop of large LED screens in Opera Australia’s Madama Butterfly (Opera Australia)

Of course, in both digitized and more traditional stagings produced by Opera Australia, language accessibility is key to programming. All Opera Australia productions involve some form of surtitles (“a translation of the text, often sung in a language other than English which can be seen on one or more screens and can be seen from most seats in each of our resident theatres”). Further, for those with visual impairments, the Company offers special “Audio Described” performances, in which headsets with audio descriptions of all scenic elements, entrances and exits, and pivotal moments are provided to all affected audience members. Of note, while a majority of Opera Australia’s productions are in a language other than English, annual seasons still include a handful of English concerts or musicals. For these musicals, captioned performances are offered regularly and explicitly detailed on their ticketing site.

Video 1: Trailer for Opera Australia’s 2022 reboot of their 2019 production of Madama Butterfly (Opera Australia)

During their 2019 season Opera Australia presented Madama Butterfly– an Italian opera composed by Giacomo Puccini in 1904– in a strictly digitized format with English surtitles at the Sydney Opera House. At the disposal of the company were five trusses supporting pairs of rotating and tracking LED screens, as well an “additional pair of three-meter-wide panels that could track side to side and an additional pair of two-meter panels downstage of the proscenium.” The scale of the production and physicality of digitized scenic elements combined with an assortment of more traditional physical elements created what was described by one critic as a “visually arresting” production of the “beloved opera.” Further, the critic stated that the digital elements were “most convincing when [they were the] most abstract.” Drawing from the previous year’s statistics, Opera Australia reports that 84 percent of attendees believed that “the digital sets added to their experience.” While not all critics and audiences responded to the digital elements with equal positivity, there was consensus that the production was captivating, “technologically slick,” and “radically different to the production that had prevailed for the previous decades”. These digitization efforts opened pathways for new and seasoned audiences alike to experience the classic Italian opera in its original language, as well as the opportunity for Opera Australia to present a larger season.

WHAT OPERA AUSTRALIA MEANS FOR THE ARTS SECTOR

As a whole, Opera Australia clearly comprehends the vitality of opera in its preserved original languages in a contemporary context. The organization’s strong, curated relationship between digitization techniques and performance-wide accessibility efforts not only make opera linguistically accessible and engaging for a modern audience, but keep audiences coming back for more. There are two primary lessons to be learned from Opera Australia that may be applied to all facets of the arts.

(1) The preservation of original languages in art does not have to deter audiences from engagement

A major deterrent to opera for US audiences is a claim that they cannot follow non-English stories. Opera Australia, in blunt terms, proves that this is definitively not true for the general public. In fact, 94 percent of surveyed attendees of the Madama Butterfly 2019 national tour said they “enjoyed that the opera was performed in its original language.” Additionally, 94 percent also claimed that they “would attend an Opera Australia performance in the future.”

In order to encourage American audiences to engage with stories from non-English origins, organizations must reanalyze how their programming is being presented, not the language the story is presented in. In order to make the United States population engage with non-English art, language cannot be deemed the villain. Programming should strive to reflect linguistic diversity and history in a way that both honors the original language and opens it up for engagement from diverse populations. Opera Australia’s high levels of engagement and satisfaction with non-English language performances through the use of surtitles and dynamic, reenergized performances prove that popular interest in non-English language art is viable.

(2) Linguistically diverse work is not inherently elitist and inaccessible

Opera is the least attended cultural or performing arts event in the United States. Largely, this lack of attendance is due to an assumption dominant from the mid-seventeenth century where patronage from royalty supported opera that the genre is strictly for the “elite.” In contradiction to this near-hegemonic belief, Opera Australia commits itself to make opera available and enjoyable for everyone. Through joint efforts for educational and outreach programming that introduces young audiences to the genre, widespread ticket discounting practices, digitization and modernization, language and disability accessibility practices, national tours, and diverse, cross-genre seasons, Opera Australia largely excels in this mission. Opera Australia’s audiences are not just opera returners, but new, curious, and engaged first-timers. The commitment of Opera Australia to its mission of opera for everyone, and openness to innovation and outreach beyond what is “traditional” for the genre not only shows hope for the re-energization of opera in popular entertainment but proves that art does not have to be conceptualized as something exclusively for society’s wealthy or “elite.”

The remaining installment of this research into the current state of linguistic accessibility and equity in the artistic sector will look to television for more examples of best practices in how questions of diversity and equity through technology can craft a truly inclusive art sector. Ultimately, the lessons provided by these case studies will point to how the arts sector can productively help consumers understand how they matter.

-

“Accessibility.” Opera Australia. Accessed December 15, 2022. https://opera.org.au/accessibility/.

“American Opera.” Article. The Library of Congress. Accessed December 15, 2022. https://www.loc.gov/item/ihas.200197506/.

“Annual Reports.” About. Opera Australia. Accessed December 15, 2022. https://opera.org.au/about/opera-australia/annual-reports/.

Bailey, Michael. “‘Not a 19th Century Art’: Inside Opera Australia’s Digital Revolution.” Financial Review. August 16, 2019. https://www.afr.com/life-and-luxury/arts-and-culture/not-a-19th-century-art-inside-opera-australia-s-digital-revolution-20190810-P52ftx.

“The Barber of Seville.” Other Events. Opera Australia. Accessed December 15, 2022. https://opera.org.au/events/national-tour/the-barber-of-seville/.

Breakfield, Margie. “Opera Houses in the United States.” Jamestown Ohio Opera House. June 8, 2012. http://www.jamestownohiooperahouse.com/website__opera_house_history.pdf.

“A Brief History of Opera.” San Francisco Opera. Accessed December 15, 2022. https://www.sfopera.com/learn/about-opera/a-brief-history-of-opera/.

Bratovich, Rita. “REVIEW: Opera Australia’s ‘Madama Butterfly’ at Sydney Opera House.” Arts & Entertainment. City Hub. July 3, 2022. https://cityhubsydney.com.au/2022/07/review-opera-australias-madama-butterfly-at-sydney-opera-house/.

Dietrich, Sandy and Erik Hernandez. “Language Use in the United States: 2019.” Publications. The United States Census Bureau. September 1, 2022. https://www.census.gov/library/publications/2022/acs/acs-50.html.

Eardley-Weaver, Sarah. “Lifting the Curtain on Opera Translation and Accessibility: Translating Opera for Audiences with Varying Sensory Ability.” University of Durham (United Kingdom). November 2013. 19–101. http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/10590/1/Sarah_Eardley-Weaver_PhD_thesis.pdf?DDD36+.

Editors. “Italian Renaissance.” The History Channel. Accessed December 15, 2022. https://www.history.com/topics/renaissance/italian-renaissance.

“Education and Outreach.” Support Us. Opera Australia. Accessed December 15, 2022. https://opera.org.au/support-us/education-and-outreach/.

Guion, David. “Opera: When Did it Become Highbrow Culture?.” Musicology for Everyone. June 19, 2017. https://music.allpurposeguru.com/2017/06/opera-highbrow-culture/#:~:text=From%20the%20middle%20of%20the,Cultural%20divisions%20became%20more%20apparent.

“History.” About. City of Williamsburg. Accessed December 15, 2022. https://www.williamsburgva.gov/488/History#:~:text=Williamsburg%20was%20founded%20as%20the,New%20World%20founded%20in%201607..

“A History of Opera in Europe.” River Cruising & Escorted Tours News. Scenic: Luxury Cruises & Tours. January 24, 2017. https://www.scenic.co.uk/news/a-history-of-opera-in-europe.

Hunter, Mary. “Some Representations of Opera Seria and Opera Buffa.” Cambridge Opera Journal 3, no. 2 (July 1991): 89 - 108. https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/cambridge-opera-journal/article/abs/some-representations-of-opera-seria-in-opera-buffa/11A21FC2858FEEFC80ABCB088984144A.

Hutchins-Viroux, Rachel. “The American Opera Boom of the 1950s and 1960s: History and Stylistic Analysis.” Revue Lisa 2, no. 3 (2004): 145 - 163. https://journals.openedition.org/lisa/2966.

King, Timothy. “Patronage and Market in the Creation of Opera Before the Institution of Intellectual Property.” Journal of Cultural Economics 25, no. 1 (2001): 21–45. http://www.jstor.org/stable/41810744.

Kornhaber, Donna and David Kornhaber. “Digging for the Roots of American Theatre.” The New York Times. March 11, 2007. https://www.nytimes.com/2007/03/11/theater/11korn.html.

Larkin, David. “A new, darker Butterfly at Opera Australia.” Opera Reviews. Bachtrack. July 1, 2019. https://bachtrack.com/review-madama-butterfly-murphy-son-gorrotxategi-opera-australia-sydney-june-2019.

Malinsky, David. “Congress Bans Theatre!.” Arts and Literature. Journal of the American Revolution. December 12, 2013. https://allthingsliberty.com/2013/12/congress-bans-theatre/.

Maurer Maurer. “A Musical Family in Colonial Virginia.” The Musical Quarterly 34, no. 3 (1948): 358–64. http://www.jstor.org/stable/739548.

Meagher, Jennifer. “Commedia Dell’arte.” Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. The Metropolitan Museum of Art. July 2007. https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/comm/hd_comm.htm.

Mitchell, Arnold. “The Professional Performing Arts: Attendance Patterns, Preferences and Motives, Volume 2.” National Arts Administration and Policy Publicans Database. Americans for the Arts. December 1984. https://www.americansforthearts.org/by-program/reports-and-data/legislation-policy/naappd/the-professional-performing-arts-attendance-patterns-preferences-and-motives-volume-2.

NEA Staff. “Why the Arts Matter.” National Endowment for the Arts Blog. The National Endowment for the Arts. September 23, 2015. https://www.arts.gov/stories/blog/2015/why-arts-matter.

“Opera Australia.” About. Opera Australia. Accessed December 15, 2022. https://opera.org.au/about/opera-australia/.

Pemberton, Marilyn. “Castrati: Did the End Justify the Means?.” Historia Magazine. January 17, 2020. https://www.historiamag.com/castrati-end-justify-means/.

Read, Bridget. “Can Opera Attract a New Generation of Fans? At La Scala, Signs of Hope.” Arts. Vogue. July 10, 2019. https://www.vogue.com/article/will-millennials-kill-opera-too-la-scala-milan.

“The Rise, Fall, and Rebirth of the Historic Opera House.” Arts and Leisure. New England Historical Society. Accessed December 15, 2022. https://newenglandhistoricalsociety.com/six-historic-opera-house/.

Robin, Natalie. “Digitizing Opera: Part One, Video.” Theatre. Live Design. August 29, 2019. https://www.livedesignonline.com/special-report/digitizing-opera-part-one-video.

Rowan, Lily. “Castrati Singers: Boys Were Castrated to Keep Their Voices at a Higher Pitch.” History Daily. June 13, 2017. https://historydaily.org/castrati-singers-boys-castrated-keep-voices-higher-pitch.

Szabó, Zoltán. “Waiting for the Robins to Nest Again: an Underwhelming Madama Butterfly in Sydney.” Opera Reviews. Bachtrach. June 30, 2022. https://bachtrack.com/review-madama-butterfly-sae-kyung-rim-torre-strong-opera-australia-june-2022.

Simington, Sarah. “The Future of Technology in Opera.” AMT Lab. October 31, 2019. https://amt-lab.org/blog/2019/10/technology-in-opera?rq=opera.

Socolof, Jerome. “It’s a Bunch of People in Horns Singing in Languages I Don’t Understand for Longer Than I Want to Listen.” Arts Blog. Americans for the Arts. April 18, 2014. https://blog.americansforthearts.org/2019/05/15/%E2%80%9Cit%E2%80%99s-a-bunch-of-people-in-horns-singing-in-languages-i-don%E2%80%99t-understand-for-longer-than-i-want-to.

Tietz, Tabea. “Jacopo Peri and the Birth of Early Opera.” Art. SciHi Blog. October 6, 2022. http://scihi.org/jacopo-peri/.

“U.S. Patterns of Arts Participation: A Full Report from the 2017 Survey of Public Participation in the Arts.” Research Publications. The National Endowment for the Arts. December 2019. https://www.arts.gov/impact/research/publications/us-patterns-arts-participation-full-report-2017-survey-public-participation-arts.

“Verified Opera Statistics.” Opera Base. Accessed December 15, 2022. https://www.operabase.com/statistics/en.

Vincent, Caitlin. “Opera’s Digital Revolution May Be the Key to Increasing the Artform’s Appeal.” The Conversation. July 30, 2018. https://theconversation.com/operas-digital-revolution-may-be-the-key-to-increasing-the-artforms-appeal-100459

“What is Baroque Music?.” About Us. Music of the Baroque. Accessed December 15, 2022. https://www.baroque.org/baroque/whatis.

Whiteney, Suzanne. “What is Opera Buffa.”Opera Explained. Opera Colorado. September 1, 2021. https://www.operacolorado.org/blog/what-is-opera-buffa/.