To read the author’s full research report on linguistic equity in the arts sector, click here.

Introduction

This article is rooted in the following assertion made by the National Endowment for the Arts:

“The arts matter because they help us understand how we matter.”

From this statement, it follows that media has the power to “tell [a] society who and what is important.” For members of minority and underrepresented demographic groups, representation in arts and entertainment not only impacts how the world sees them, but guides how they see themselves. Identity-based association with creators, actors, or performances facilitated through accurate representation in entertainment can “break down barriers, open [up] new ideas, create powerful role models, and … be a source of inspiration” as one's own identity is strengthened through its represented existence on stage or screen. However, alongside the positive identity-building potential of representation in the arts come the equally powerful threats of underrepresentation and inaccessibility to these minority identities. Intuitively, when the arts lack accessibility and proper representation, harm comes to those who would be otherwise interested in or physically able to engage with the field.

Particularly in the wake of the 2020 murders of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, and Ahmaud Arbery, artistic organizations have made strides to increase diversity, cultural-sensitivity, and broad cultural equity. Despite these strides, however, internationally-recognized artistic advocacy and service organizations such as Americans for the Arts (AFTA) are regularly criticized for “hoarding power and blocking pathways for professional advancement in the field for BIPOC arts leaders.” However, language-based diversity and the related questions of physical accessibility are regularly left out of these conversations; whether conscious or not, DEI efforts in popular arts and media regularly function on the outskirts of language-based representation and accessibility. As will be expanded upon later in this article, in the nation’s current artistic environment, a lack of language-based representation and diversity are significantly stifling how the United State’s linguistically-diverse society is able to engage with the arts.

As illustrated above, in the United States alone, the US Census Bureau reports that the proportion of residents who speak a language other than English at home has increased by a factor of 194.0% between 1980 and 2019. This statistic is especially striking when compared to the fact that the proportion of residents who only speak English in the home increased only by a factor of 28.8% over the same time period. As will be expanded upon further in this article, identity is strongly tied to language-rooted culture. In her research on gender and identity, Mary Bucholtz explains that nearly all linguistic phenomena (ranging from discourse to slang to formal writing) are socially structured. Under this framework, “speakers use language to project their identities” and using language, “identities emerge in practice, through the combined efforts of [linguistic] structure and [individual] agency.” Language and intertwined cultural heritage are key to individual identity. It then follows that any lack of language-based representation and accessibility in the arts are a failure of diversity and representation in the sector.

At present, linguistic representation and language-based accessibility are far behind the (equally impactful) strides for race, gender-identity, and sexuality equity in the arts. This article examines the current state of language in the arts, and breaks down why such representation matters not only for individuals, but the artistic sector as a whole. In future sections, additional exploration will be presented on how technology may be integrated alongside systemic linguistic-consciousness to propel equal representation. Ultimately, these opportunities can create an artistic community where users of all forms of language may use the arts “to understand how [they] matter.”

The Impacts of Linguistic Intervention and Development on Identity

Prior to examining the current state of language diversity and accessibility in the arts, it is crucial to first solidify why exactly such representation matters.

Linguistic Empowerment Through Performing Arts

“Young women who have an increased understanding and awareness of their voices, have an increased ability to positively impact their self-advocacy to express themselves, and contribute to their communities.”

In 2018, researchers Sarah Fahmy, Pui-Fong Kan, and Jen Walentas Lewon implemented a “theatre-based vocal empowerment program” on 55 total bilingual woman from Egyptian cities Alexandria and Aswan to measure intervention impacts on “the vocal and language characteristics and self-perceptions of [these] young bilingual … [participants].” Researchers asserted that “young women who have an increased understanding and awareness of their voices, have an increased ability to positively impact their self-advocacy to express themselves, and contribute to their communities.” In other words, the team predicted that increased language stimulation and representation through the use of theatrical programming would strengthen self-perceived identity and advocacy in public settings.

The study’s theatre-based vocal empowerment program included interwoven “dramatic techniques and physical movement to enhance participants' understanding of the biological, psychological, and emotional functions of voice production” in an explicitly improvisational theatrical setting. All selected participants spoke Arabic natively, and had studied English in school with varying levels of proficiency and self-perceptions of skill in each language. Following the 12-day intervention program, results were measured for both Arabic and English in terms of speech production tasks (lexical diversity, grammatical complexity, speaking rates, and fundamental frequency) and a self-perception survey. All results were compared to the same measures taken prior to the theatrically-based empowerment program.

“Theatre is a community-based, collective activity that engages [individuals] in an embodied way to practice using their voices with confidence to speak up about community concerns they care about.”

Ultimately, results supported the researchers’ hypothesis that participation in the applied and improvisational programming had positive impacts on participants “vocal and language production skills and their vocal empowerment knowledge” in both of their spoken languages. Interestingly, while intervention had positive impacts on women from both cities, researchers found that individual results were stratified in direct correlation with “socio-economic, educational, and language backgrounds.” In the context of the present investigation, linguistic representation and its promotion through the arts has positive effects on language-based identity.

Exposure to languages in conjunction with the arts has the power to drive identity-based intervention and support for individuals of all social, economic, and regional classes. As the researchers put it, “theatre is a community-based, collective activity that engages [individuals] in an embodied way to practice using their voices with confidence to speak up about community concerns they care about.” Language-based artistic engagement affects not only how speakers view themselves, but how they engage with society on a larger scale.

Linguistic Diversity in the Digital Age

The field of linguistics encompasses all facets of communication. The digital age has triggered “an explosion of new vocabularies, genres, and styles and by reshaping literacy practices.” While TikTok trends or Twitter-speak won’t likely be sprinkled into an opera as an outcome of language accessibility or representation efforts in the arts, language in the digital age is a useful tool to convey how language is able to shape identity within communities and individuals.

“The digital ... transforms identity [and in turn allows for] the construction and performance of multiple identities.”

Summarizing this language-associated digital development, researcher Ron Darvin writes that through the rise of the internet “new spaces of language acquisition and socialization” have been created and “social media capabilities have facilitated cross-language interaction” with “transcultural and translingual practices.” In other words, the accessibility of linguistic diversity has increased exponentially with the global introduction of social media and the internet. As a result of the previously-discussed dynamic role of language in identity formation, “the digital also transforms identity.” Because the digital world provides many unique spaces and communities, individuals are able to move through (or, perform) diverse identities across various platforms and means of communication. Digital expansion has facilitated the growth of increased, cross-cultural knowledge bases while simultaneously enabling “the construction and performance of multiple identities.” As a whole, the digital revolution has opened vast opportunities for rapid identity formation and change in a large-scale, linguistically diverse ecosystem.

Virtual identities are defined by how an individual commands language on digital platforms. For example, linguists have uncovered a unique discourse style utilized exclusively on Facebook marked by high degrees of intensification including exaggerated quantifiers, frequent boosters (e.g. very, really, so), capitalization, and repetition relative to both non-virtual communication and language on other social platforms. Users adapt their identities to the linguistic norms of their surroundings even in digital environments.

“The ability to assert identity becomes inextricably linked to being able to gain the attention of specific audiences and to use innovative communicative strategies.”

Further, multilingual encounters have grown as individuals are able to connect with an otherwise unreachable international network. In the context of the present research, the rise of the internet and virtual communication has led to language preservation through an “increased use of local languages among diasporic communities online” and the resulting assertion of otherwise geographically isolated linguistic identities on a global scale. In other words, the reach of “digital media … enables the use of minority languages” and strengthening of individual and collective identities rooted in language. Within this, however, the “ability to assert identity becomes inextricably linked to being able to gain the attention of specific audiences and to use innovative communicative strategies.”

For the arts, the strengthening of linguistically-driven individual identity and thriving virtual, language-based communities through the digital revolution proves the viability and importance of language representation and accessibility. The arts can provide a valuable tool in ensuring that linguistic minorities are represented. As asserted earlier, media and entertainment can tell a society what matters. In turn, productions from trusted arts organizations and producers hold the power to tell audiences that these minority voices and identities crafted through language do indeed matter and have a place in diversity, equity, and inclusion conversations.

The Present State of Engagement and Language Representation in the Arts

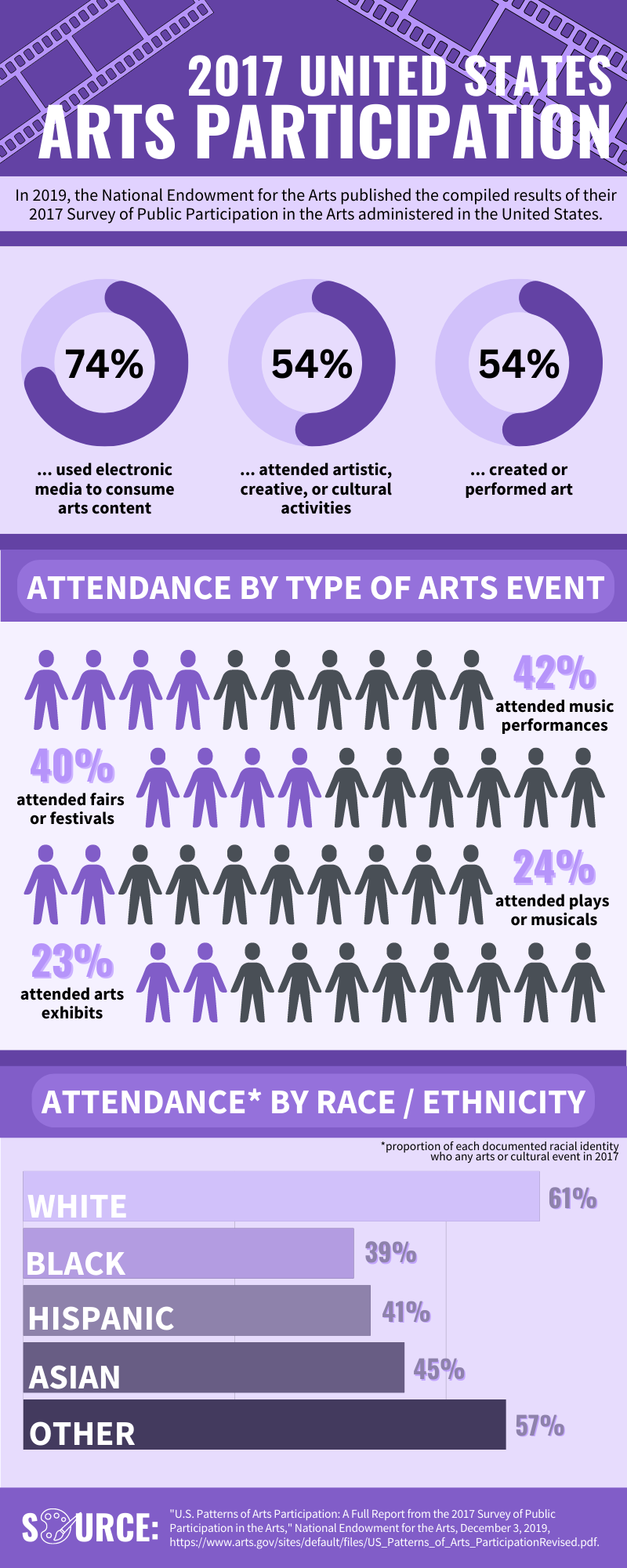

Figure 2: A brief summary of the National Endowment for the Art’s 2017 study conducted on arts participation in the United States

Focusing once again on the United States, in 2021 the nation was “the leading world art market” and made up for “43% of the global art market value.” In 2017 the National Endowment for the Arts reported that 74% of American adults “used electronic media to consume artistic or arts related content” and 54% “attended artistic, creative, or cultural activities.” Between creators and performers alike, 62% of adults who participated in performing arts activities “did so to spend time with family and friends.” The arts are highly prominent in the United States, and–as discussed above–foster community and, in turn, identity.

Despite striking artistic participation however, English is overwhelmingly the primary language of all artistic endeavors in the United States. To illustrate, in the film industry between 2003 and 2017, non-English language movies resulted in only 1.1% of total domestic box office revenue. In opera–a medium overwhelmingly not performed in English–2021 received the lowest attendance of any performing art. Over time, opera engagement has solely decreased both in terms of overall frequency and the number of times an individual would attend a performance in a single year. English, of course, is the sole national language of the country. However, as explored above, 1 in 5 Americans speak a language other than English at home. The arts in the United States are not linguistically representative of the linguistically diverse population. English is the hegemonic language of the arts in the nation. Such a discrepancy between this linguistic hegemony and the linguistic diversity of the country as a whole prevents any potential for minority identity-building and representation.

Linguistic representation and language-based accessibility are crucial in creating an artistic sector that is truly inclusive and allows individuals and communities from all backgrounds to use the arts to strengthen their identities. At present, the arts largely fall flat in terms of the potential for linguistic diversity in the sector. However, some organizations are taking notable strides to increase linguistic representation and accessibility. Largely, such strides are enacted through the use of technology.

In forthcoming research, this study will sequentially analyze examples from professional opera, theatrical, and Netflix programming in which artistic organizations used technology to actively increase linguistic equity in the arts. These case studies will not only explore the present state of linguistic representation and accessibility in the arts, but they will also offer cross-sectional applications to varying domains and branches of the arts. Conversations of linguistic equity and accessibility are integral to a truly diverse and productive artistic future, and the best way to formalize a holistic path forward is through the examination of organizations that have already implemented such integral conversations into their missions and practices.

Figure 3: A preview of upcoming case studies that feature organizations who use technology to facilitate linguistic diversity and representation in the arts.

-

Abbott, Jonathan. “Representation in Media Matters.” GBH. Accessed October 18, 2022. https://www.wgbh.org/foundation/representation-in-media-matters.

Blair, Elizabeth. “‘Americans for the Arts’ Promises More Racial and Cultural Equity.” NPR. December 3, 2020. https://www.npr.org/2020/12/03/942451376/americans-for-the-arts-promises-more-racial-and-cultural-equity.

Blair, Rhonda and Amy Cook. Theatre, Performance and Cognition: Languages, Bodies and Ecologies, Performance and Science. London: Methuen Drama, 2016. https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=nlebk&AN=1158977&site=ehost-live&scope=site.

Bucholtz, Mary. “Why be Normal?: Language and Identity Practices in a Community of Nerd Girls.” Language in Society 28, no. 1 (1999): 203 – 223. Accessed October 19, 2022. https://www.cambridge.org/core/services/aop-cambridge-core/content/view/5F3744D7AB7FC0EA91079650D14E5ABA/S0047404599002043a.pdf/div-class-title-why-be-normal-language-and-identity-practices-in-a-community-of-nerd-girls-div.pdf.

Castellini, Bri. “Why Representation Matters.” Pipeline Artists. February 9, 2021. https://pipelineartists.com/why-representation-matters-in-arts/.

Darvin, Ron. “Language and Identity in the Digital Age.” The Routledge Handbook of Language and Identity, ed. Sian Preece, Routledge (Oxfordshire, England, February 18, 2016), 523 – 540. Accessed October 21, 2022. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/303838217_Language_and_identity_in_the_digital_age.

Dietrich, Sandy and Erik Hernandez. “Language Use in the United States: 2019.” United States Census Bureau. September 1, 2022. https://www.census.gov/library/publications/2022/acs/acs-50.html.

“Distribution of the Global Art Market Value in 2021, by Country.” Arts and Culture. Statista. March 31, 2022. statista.com/statistics/885531/global-art-market-share-by-country/#:~:text=The%20United%20States%20was%20the,the%20global%20art%20market%20value

Fahmy, Sarah, Pui-Fong Kan, and Jen Walentas Lewon. “The Effects of Theatre-Based Vocal Empowerment on Young Egyptian Women’s Vocal and Language Characteristics,” ed. Dionysios Tafiadis. Plos One 16, no. 12 (December 31, 2021): 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0261294.

“How Many Non-English Language Films Get a US Theatrical Release?.” Articles. Stephen Follows: Film Data and Education. April 9, 2018. https://stephenfollows.com/how-many-non-english-language-films-get-us-theatrical-release/.

Muraco, Julie C. and Nolen V. Bivens. “A Message to the Field from the Board of Directors of Americans for the Arts: Report to the Field on the Task Force for Racial and Cultural Equity.” Arts Blog. Americans for the Arts. August 18, 2021. https://blog.americansforthearts.org/2021/08/18/a-message-to-the-field-from-the-board-of-directors-of-americans-for-the-arts-report-to-the-field-on?utm_source=MagnetMail&utm_medium=email&utm_term=mwalker%40artsusa.org&utm_content=11.18.20_ResponseTo2020&utm_campaign=Addressing%20the%20Urgent%20Challenges%20of%20-020.

NEA Staff. “Why the Arts Matter.” National Endowment for the Arts. September 23, 2015. https://www.arts.gov/stories/blog/2015/why-arts-matter.

"U.S. Patterns of Arts Participation: A Full Report from the 2017 Survey of Public Participation in the Arts." National Endowment for the Arts. December 3, 2019. https://www.arts.gov/sites/default/files/US_Patterns_of_Arts_ParticipationRevised.pdf.