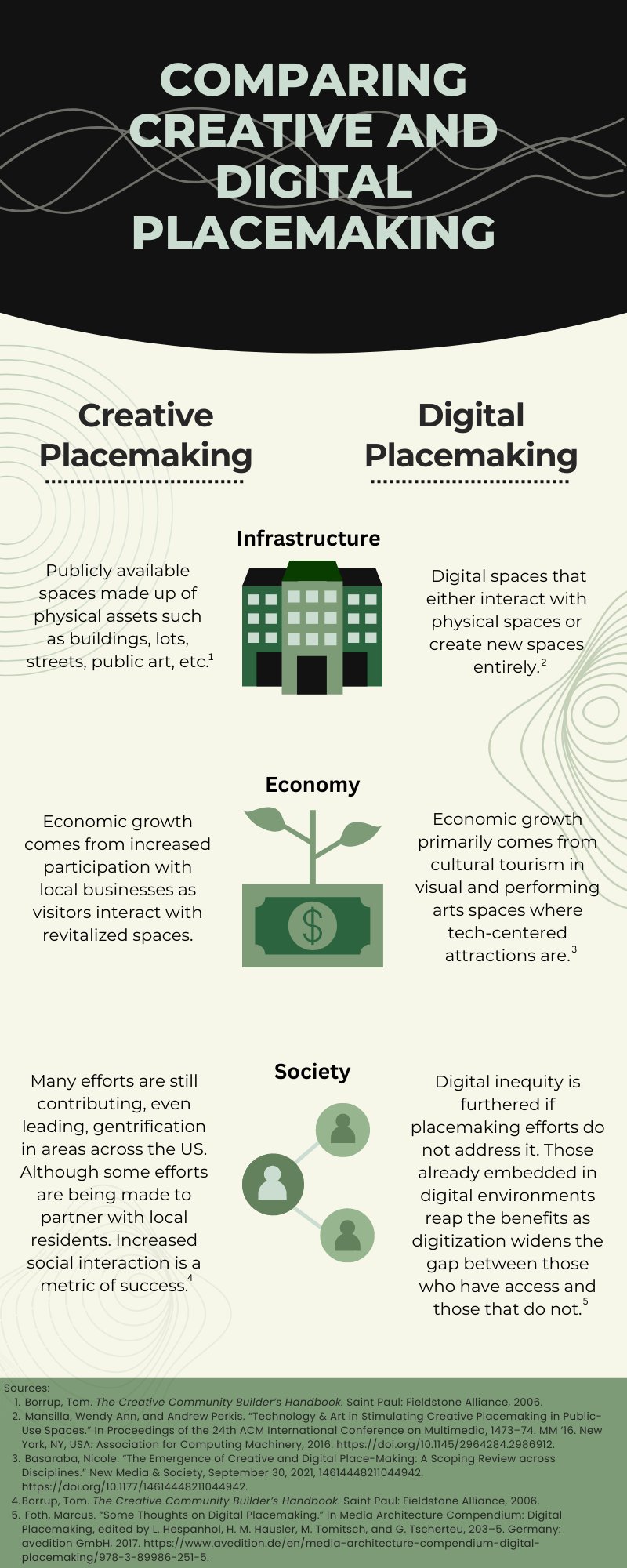

As technology advances and becomes more ubiquitous in our lives, even creative placemaking has evolved to include a digital arm. At the beginning of the pandemic, technology assisted many Americans in attempting to maintain some semblance of a normal life. Many employees worked from home, students attended school virtually, and arts organizations created digital events to connect to their communities. However, a significant portion of the US population did not have equal access to these benefits due to the digital inequities that the pandemic exposed. This article addresses the foundational frameworks of digital placemaking, its similarities and differences to creative placemaking, and the dangerous potential for perpetuating the digital divide and digital gentrification unless governments set an appropriate course of action.

Impact

Stemming from the concept of creative placemaking, digital placemaking aims to create meaning and a sense of attachment to a place. Digital placemaking practices utilize digital media to create a sense of place for oneself and/or others. As the relationship between physical and digital landscapes grows, digital placemaking allows us to symbolically place ourselves in a virtual environment through digitally immersive or enhanced experiences using a variety of digital media such as augmented reality or virtual reality. On a larger scale, digital placemaking is rooted in the field of urban design, which focuses on city planning and economic improvement. However, many initiatives focus on individual experiences that explore the relationship between physical and digital spaces.

Increasingly, the intersection of technology and art is being used to stimulate creative placemaking in public-use spaces. Digital technologies have become more prominent in creative placemaking strategies. An emphasis has also been placed on the narrative aspect of digital placemaking experiences. Interactive digital narratives allow for a collective experience, whereas most of the current research on digital placemaking focuses on individual user experiences.

Two areas where digital placemaking efforts have primarily been made are the cultural tourism and heritage sectors. The narrative element of digital experiences applies heavily to the cultural heritage sector. Many new media technologies in galleries, libraries, archives, and museums are used to develop new visitor experiences through creative storytelling. Some technologies that have been utilized in these spaces are virtual reality, augmented reality, 3-D reconstruction, and 360 photography. Various strategies in combination with these technologies have been used to attract visitors and tourists to particular locations. The goals of these efforts can be wide-ranging. On the individual scope, users feel a sense of control over their place and are more connected to their physical surroundings. Through a narrative-focused approach to digital placemaking, users gain an understanding of the environment they inhabit and perhaps a sense of “home.” In the context of cities, which many of these efforts pertain to, there are economic benefits that come from increased tourism. For current residents, a revitalization of their space may bring about more sustainable ways of life and create meaning by highlighting local stories, relationships, memories, and rituals.

Saskia Witteborn’s research on the impact of digital placemaking on forced migrants shows the positive impacts of the use of digital media. Through digital practices, migrants have used social media to create a sense of past, present, and aspirational future. Using this digital medium has assisted in creating a sense of home and collective cultural places of belonging for displaced people through several tasks. Migrants use digital media to navigate their new surroundings, search for information, communicate with relatives and friends in their home country, and find a local community with which to congregate.

Figure 1 Source: Author

Despite its benefits, there have been several criticisms of digital placemaking efforts. As is the case with any placemaking efforts, the history of gentrification and displacement in any location cannot, nor should it, be erased. When it comes to digital placemaking, narrative techniques run the risk of ignoring the history that came before. Glossing over unpleasant historical facts about a place may be the result of designing places in ways that suit the placemakers and their funders more than the current or future occupants. Past occupants of such spaces have borne the brunt of the consequences that fell out of this strategy (or lack thereof). This criticism applies not only to the finished product but also to the accessibility and use of a place after its completion. Purely pursuing placemaking for economic benefits denies the socio-cultural opportunities that genuine placemaking can offer. Treating people that occupy a space as clients in need of a service rather than as citizens in need of a transformation is a major fault of placemaking efforts.

Finally, many placemaking efforts have focused on a smaller cluster or neighborhood of a city rather than a city as a whole, which can only further the gentrification and displacement of various groups.

It is crucial now more than ever to consider these potential harms when creating public spaces, especially when taking into account the impact COVID-19 has had on exposing existing inequities and lack of access to basic digital services, such as broadband. Before realizing the full potential of digital placemaking, these inequities need to be addressed.

Digital Equity

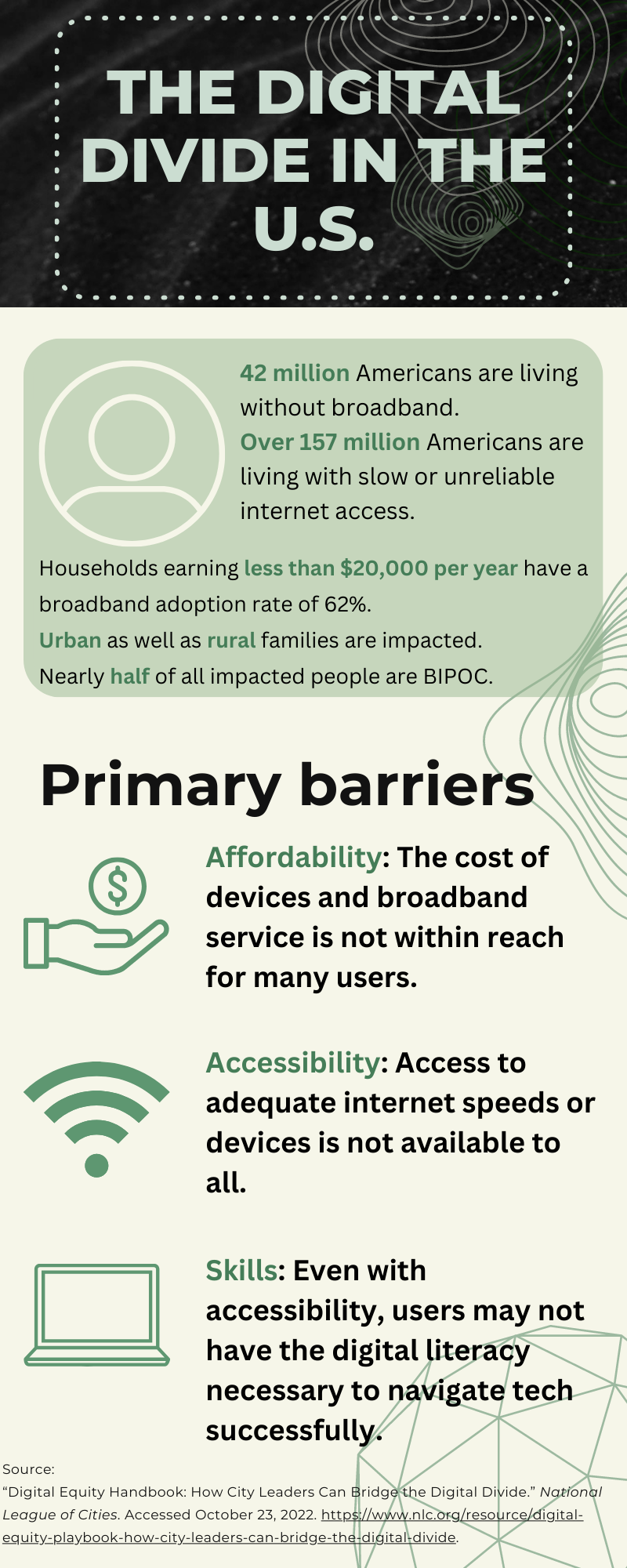

One of the primary issues with digital placemaking is its lack of contribution to digital equity. A true collective experience cannot take place when certain populations lack the access and/or ability to participate in events, particularly in a digital space. Digital inequity has been entrenched as a significant barrier to education, employment, healthcare, and commerce in the 21st century.

Marcus Froth discusses two timelines for placemaking which have very different outcomes. Natural placemaking occurs as humans leave their marks on cities through occupations, inhibition, decoration, renovation, and many other activities. Accelerated placemaking, on the other hand, occurs when developers seek to quickly build urban developments without ethical consideration for how their actions may contribute to gentrification. Both timelines are relevant to digital placemaking if they utilize digital elements such as public wifi, urban screen, or media architecture. Froth offers the prospect that the role of digital placemaking in cities can increase growth and efficiency.

What is conditional upon this growth, however, is the shifting of the role of governments as collaborators and the role of their citizens as co-creators. Froth advocates for boundary-crossing dialogue, arguing that it is necessary to establish a middle-out approach rather than the top-down approach that has contributed to so many long-standing problems. The problems proliferated by poorly assembled digital placemaking initiatives are symptoms of a larger, global problem - the digital divide.

Researcher, scholar, and professor Massimo Ragnedda established three levels of the digital divide:

Level 1: Accessing the internet

Level 2: Digital skills and capabilities

Level 3: Tangible benefits of using the internet

Level one, “accessing the internet”, is at the foundation of the digital divide. Ragnedda posits that the policies, investments in infrastructure, and technological developments are a reflection of the broader socio-economic differences in countries and states. Level two outlines the gaps that exist among citizens in the ability to participate and enjoy the benefits of the information society. Besides merely having access to the internet, digital literacy and competency are significantly lacking in some portions of the population as technology advances. As more and more activities transition to an online space, this issue becomes more imperative. Level three amalgamates levels one and two to assess the impact on citizens’ quality of life in not being able to access digital services. Such services include, but are not limited to, public services, online health services, and e-commerce.

Although Ragnedda’s article on the three levels of the digital divide is based on Eastern European countries, his ideas have manifested in various contexts in the United States. A 2019 analysis by Microsoft found that an estimated 42 million Americans do not have broadband access, and roughly 157 million live with slow or unreliable internet service. After causing a major disruption in learning for K-12 students, the COVID-19 pandemic compounded present educational inequities and revealed that students of color were less able to access remote learning environments. The K-12 digital equity gap is defined by the kinds of technology students do or do not have access to, which was present long before the pandemic took place in 2020. Simply investing in new technologies has the potential to create barriers for low-income students, which then leads to a greater disconnect between college readiness and the digital ecosystem.

One of the biggest mistakes that can be made in digital equity and placemaking efforts is making the assumption that because access is provided, it is inclusive. Digital literacy, as Ragnedda points out, is a significant portion of the equation. Solutions to the digital divide must include increasing broadband access and disseminating knowledge on digital skills.

Figure 2 Source: Author

Conclusion and Future Research Needs

Many scholars and experts agree that further research on digital placemaking is necessary. COVID has shown that digital skills, high-speed internet, and reliable hardware and software are essential conditions for work, health, social interaction, and education, thus influencing the quality of life. Increasing public access to digital services and digital literacy education can have significant contributions to the quality of life for all Americans.

Zack Quaintance pointed out that federal data on digital equity is lacking. This lack of data presents a challenge in linking digital placemaking efforts to digital equity. But just as creative placemaking can utilize arts and culture to create inclusion and equity in communities, digital placemaking has the same potential as we move into a more technology-centered future locally, nationally, and globally.

-

Aguilar, Stephen J. “Guidelines and Tools for Promoting Digital Equity.” Information and Learning Sciences 121, no. 5/6 (January 1, 2020): 285–99. https://doi.org/10.1108/ILS-04-2020-0084.

Basaraba, Nicole. “The Emergence of Creative and Digital Place-Making: A Scoping Review across Disciplines.” New Media & Society, September 30, 2021. https://doi.org/10.1177/14614448211044942.

“Digital Equity Handbook: How City Leaders Can Bridge the Digital Divide.” National League of Cities. Accessed October 23, 2022. https://www.nlc.org/resource/digital-equity-playbook-how-city-leaders-can-bridge-the-digital-divide.

Foth, Marcus. “Some Thoughts on Digital Placemaking.” In Media Architecture Compendium: Digital Placemaking, edited by L. Hespanhol, H. M. Hausler, M. Tomitsch, and G. Tscherteu, 203–5. Germany: avedition GmbH, 2017. https://www.avedition.de/en/media-architecture-compendium-digital-placemaking/978-3-89986-251-5.

Halegoua, Germaine, and Erika Polson. “Exploring ‘Digital Placemaking.’” Convergence 27, no.

3 (June 1, 2021): 573–78. https://doi.org/10.1177/13548565211014828.

Mansilla, Wendy Ann, and Andrew Perkis. “Technology & Art in Stimulating Creative

Placemaking in Public-Use Spaces.” In Proceedings of the 24th ACM International

Conference on Multimedia, 1473–74. MM ’16. New York, NY, USA: Association for Computing Machinery, 2016. https://doi.org/10.1145/2964284.2986912.

Northumbria University, Massimo Ragnedda, and Hanna Kreitem. “The Three Levels of Digital

Divide in East EU Countries.” World of Media. Journal of Russian Media and Journalism

Studies 1, no. 4 (December 1, 2018). https://doi.org/10.30547/worldofmedia.4.2018.1.

Quaintance, Zack. “Digital Equity Takes Center Stage in U.S. Cities Post COVID.” Government

Technology. March 2022.

https://www.govtech.com/civic/digital-equity-takes-center-stage-in-u-s-cities-post-covid.

Sparviero, Sergio, and Massimo Ragnedda. “Towards Digital Sustainability: The Long Journey

to the Sustainable Development Goals 2030.” Digital Policy, Regulation and Governance

23, no. 3 (January 1, 2021): 216–28. https://doi.org/10.1108/DPRG-01-2021-0015.

What is “Creative Placemaking”?Americans for the Arts. Accessed November 1, 2022. https://www.americansforthearts.org/sites/default/files/ROW-Creative-Placemaking-handout.doc.pdf.

Witteborn, Saskia. “Digital Placemaking and the Datafication of Forced Migrants.” Convergence

27, no. 3 (June 1, 2021): 637–48. https://doi.org/10.1177/13548565211003876.