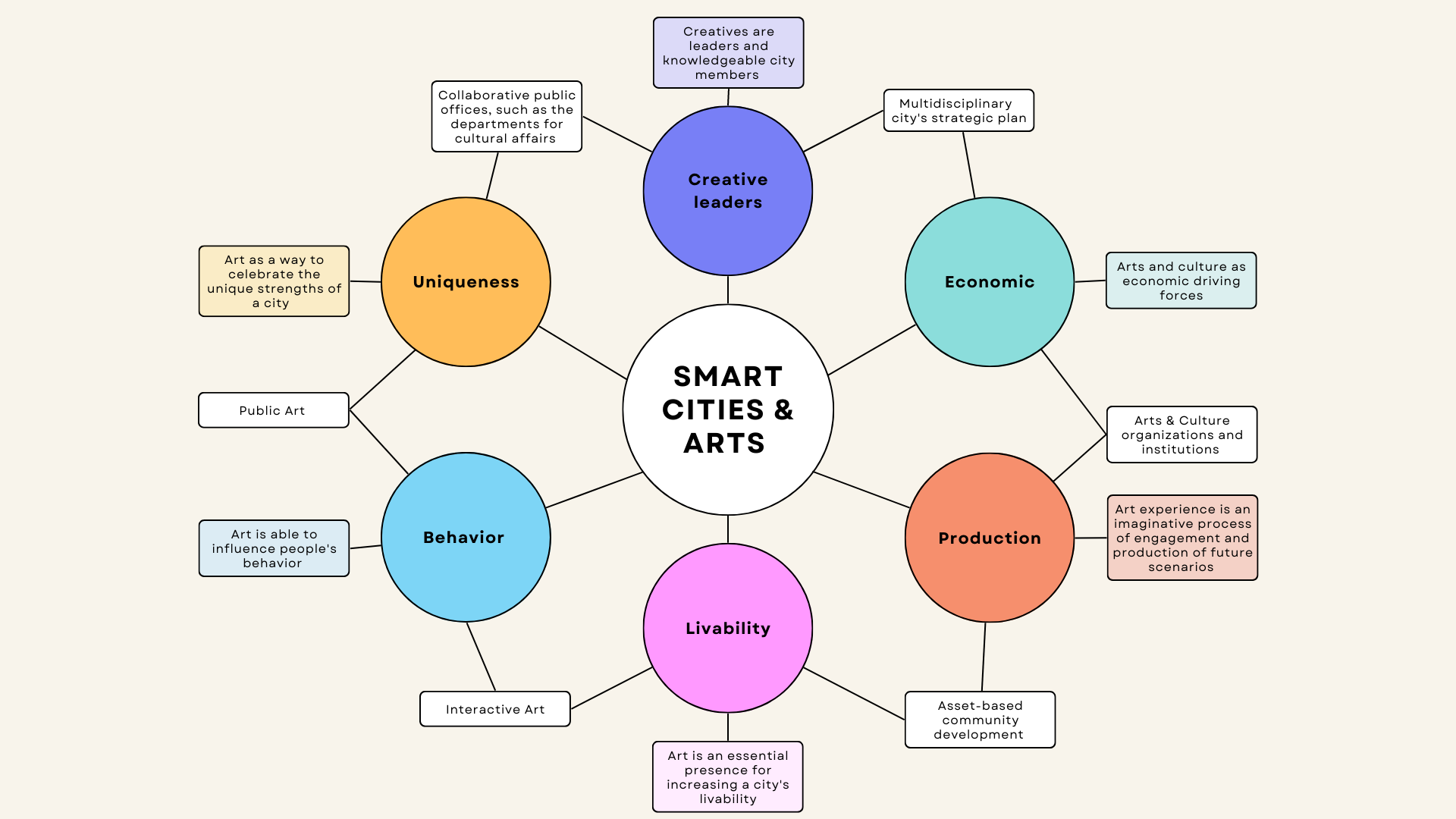

In the predecessor of this article, “The Need for Art in the Smart City”, technology is discussed as being used on the one hand to innovate, improve and explore new urban infrastructure to improve a variety of factors, such as security, sustainability, efficiency, etc. On the other hand, the incorporation of innovative technologies into the realm of art has opened up new possibilities for interactivity, accessibility, and expression. The relationship between art and smart cities has been summarized in six main roles:

· To celebrate the unique strengths of a city

· As an economic driving force

· To influence people’s information behavior

· As an imaginative process of engagement and production of future scenarios

· As an essential presence for increasing a city’s livability

· As a possibility to involve creative leaders in municipalities and decision-making processes

Figure 1: Infographic of the role of arts & culture in modern smart cities. Source: Author

This article examines the perspectives of citizens, participants, and audiences in relation to urban infrastructure and public artworks. Smart technological development should prioritize the needs and interests of individuals over the technology itself. In the context of a smart city, the goal is not simply to install digital interfaces in traditional infrastructure or streamline city operations, but rather to use technology and data in a purposeful manner to facilitate informed decision-making and enhance the overall quality of life.

In an interview with Karen Lightman, Executive Director of the Metro21: Smart Cities Institute, she explored the potentiality of art and technology within smart city infrastructure. According to her, the main concept is the idea of connectivity. This term encompasses two different but connected meanings: a sense of belonging, bond, and unity among citizens, and the opportunity for interactive engagement. Art has the potential to create opportunities for both, meaning that technology and art can be used to create a sense of connection and dialogue within a community. During the interview, Lightman mentioned the use of chatbot technology to facilitate engagement with public art as an example of how technology can be used to connect people with their surroundings and with each other. Lightman also discussed the importance of understanding the audience for different types of art and creating messages and interactions that are appropriate and engaging, as a way to foster a sense of connection with the community.

But connectivity can also refer to the ways in which technology can be used to connect people with information and resources. For example, the use of interactive, rather than static, information about public art as a way to facilitate engagement and connection with the community. In this instance, this referred to the difficulty of municipalities and public art commissions to create user-friendly experiences to both promote, sustain and use public art to create a dialogue with their audiences. Furthermore, the power of art and technology in creating a sense of connection between citizens and their environment creates the potential for these tools to be used to facilitate citizen participation in the design and development of smart cities.

Overall, the concept of connectivity in this context refers to the ways in which technology and art can be used to create connections and facilitate engagement and dialogue within a community, as well as to connect people with information and resources. Public artworks can employ the use of technology to be experienced or as part of their composition, and their interactive and engaging feature can be generated in different ways.

An example of public art that is digitally created is “Art on theMART” in Chicago. Art on theMART is the largest permanent digital art projection in the world, projecting contemporary artwork across the 2.5 acre river-façade of theMART. This incredible example of digital public launched in 2018, and at its opening event attracted more than 32,000 people to the Riverwalk in downtown Chicago, “transforming its urban context.”

Figure 2: Art on theMART, a permanent public art project in collaboration with the City of Chicago.

This project aims to provide public access to innovative contemporary artwork for the thousands of visitors and residents in Chicago. Furthermore, the MART is the largest privately held commercial building in the United States, and it is one of the world’s leading commercial buildings, wholesale design centers and the preeminent international business location in Chicago. It is therefore quite significant the decision of the City of Chicago to partner with the MART owner, Vornado Realty Trust, to create this public project.

As Lightman also noted and explored in the interview, public art can also have, in addition to its aesthetic and social functions, a relevant engagement analytics tool. Using technology to interact with a certain public artwork (or perhaps with the collection of public artworks in a city), arts can become the way in which data about human engagement and interaction are collected. And not only how people interact with the artwork itself, but also how they use and enjoy the technology employed during that experience.

The example about the use of chatbots is exactly what Lightman was referring to while expanding the concept of public art that uses technology to collect data about how the audience engages and interacts. The City of Pittsburgh had a significant investment in public art, including memorials, and sought to improve its understanding of the impact of these installations on the community through a technology-based engagement platform. This platform allowed for data collection through the use of smart technology, such as beacons and QR codes, and social engagement tools like unique hashtag campaigns. The project aimed to track and measure the social, economic, and transportation impacts of public art, and potentially discover additional impacts through its research. The results of this project were further used by both the Pittsburgh School of Design and the Pittsburgh Arts Commission.

From the perspective of a smart city, the use of technology in public art can serve as an educational tool for individuals to become more comfortable with using digital devices to interact with their surroundings and has the potential to foster trust-based dialogues with the community. The choice of whether or not to engage with the technology is left to the viewer, as the goal is to enhance and enrich the experience of the art, which can still be accessed regardless of the level of engagement with technology. By choosing to engage with the art and allowing the technology to collect data about this interaction, individuals can participate in the experience that has been designed.

Technology has the potential to improve the quality of life and can be a valuable tool for connecting individuals and building a sense of belonging within a community. Public art offers the opportunity to create accessible, open, and diverse experiences for a wide range of audiences. If implemented intentionally, technology can create new touchpoints of interaction between citizens, making the potential roles of public art multifaceted. Connecting public art to technology, or generating it digitally, can lead to the creation of new experiences with potentially greater impacts.

But for public art and technology to have a greater, positive and more efficient impact, municipalities need to develop the system, the policies and the enforcement plans to promote and sustain interactive public art. Smart city municipalities struggle to create interactive experiences and to convey the potentiality of interconnectivity through technology, therefore how they act and what they focus on has to be improved. Chicago comes back as a great example of this practice.

“But as Chicago powers forward as an engine of creative life, we ought not to forget that public art isn’t just one discipline — it isn’t just sculptures and statues, it’s not only murals on walls. It’s how we as a city bring artistic vision to our streets and to the public realm. By engaging in public art, we bring value, meaning, and pride to Chicago”

Figure 3: Jaume Plensa, Crown Fountain, Millenium Park Chicago.

In 2012, the Chicago Cultural Plan, presented by Mayor Rahm Emanuel and the Chicago Department of Cultural Affairs and Special Events, proposed that expanding art in public places could be a core strategy for elevating and expanding neighborhood cultural assets and a sense of place. According to the plan, the goal was to "embrace public art as a defining characteristic of Chicago" and "embed the arts as a presence in daily Chicago life," viewing art as a vital and natural resource that should be nurtured and delivered to all citizens, particularly youth. To achieve this, the plan established the arts as a priority in urban planning and create a network of professionals, institutions, community groups, and funders to support public art throughout the city. In order to achieve this, the plan outlined seven main goals; one strategy was the update of the city's Percent for Art Program, which included the development of clear roles and responsibilities to ensure the efficient and timely administration of the program. The plan also called for the establishment of clear and transparent governmental practices, as well as the convening of city and community stakeholders to advance a shared vision and ensure the effective and strategic implementation of the public art program.

Other strategies outlined in the plan included the expansion of resources to support the creation of public art throughout the city through the identification of grant and funding opportunities and the promotion of artful design and the inclusion of public art in city infrastructure projects. Advancing programs that support artists, neighborhoods, and the public good through the activation of civic and public spaces and temporary public art installations was also a key goal.

In addition, the Chicago Cultural Plan 2012 sought to strengthen the city's collection management systems, through the improvement of tools and strategies for tracking and completing public art projects and their ongoing maintenance needs. The plan also called for the support of the work that artists and organizations do to create public art, through professional development and capacity-building programs for artists and community organizations. Finally, the plan aimed to build awareness of and engagement with Chicago's public art, through the creation of interactive and participatory educational content in the form of maps, tours, and guides that engage audiences.

The selection of Chicago as the focus of this research was not arbitrary. The city serves as a valuable example of both a smart city infrastructure and a municipality that places a strong emphasis on the role of public art. It is important for arts managers, artists, designers, architects, and other professionals to be included in the decision-making process for the development of cities and the integration of arts and cultural institutions into the discussion of the future of smart cities. An open, interdisciplinary dialogue can lay the foundation for a more robust future that is centered on the evolving needs and values of citizens.

-

“Chicago Public Art Plan,” n.d.

“Chicago Public Art Plan.” Accessed December 16, 2022. https://www.chicago.gov/content/city/en/depts/dca/supp_info/yopa1.html.

Kim, Krista. “In the Metaverse, Life Imitates Art.” The New York Times, June 16, 2022, sec. Special Series. https://www.nytimes.com/2022/06/16/special-series/krista-kim-metaverse-nft-art-reality.html.

Lightman, Karen. The role of public art in the smart city infrastructure, Interview with the author November 30, 2022.

Schilke, Charles Noel. “Raising the IQ of Smart Cities: Chicago’s ‘Array of Things’ Urban Data Device.” Real Estate Issues, Spring 2017, 69–74.

University, Carnegie Mellon. “Karen Lightman - Metro21: Smart Cities Institute - Carnegie Mellon University.” Accessed December 16, 2022. https://www.cmu.edu/metro21/people/karen-lightman.html.

———. “Public Art + IoT = An Engaged Civic Space - Metro21: Smart Cities Institute - Carnegie Mellon University,” $dateFormat. https://www.cmu.edu/metro21/projects/smart-infrastructure/public-art-iot-an-engaged-civic-space.html.

Smart Cities Dive. “With IT Modernization Plan, Chicago Aims for More Accessible, Transparent and Secure Data.” Accessed October 24, 2022. https://www.smartcitiesdive.com/news/chicago-technology-it-modernization-plan-digital-service/627078/.