How and within which frameworks are artists part of the future city? Is art a critical element in the relationship between future cities and future citizens?

A new era of art and technology

New trends such as NFTs, artificial intelligence, hybrid intelligence, augmented reality, generative algorithm-based artworks, immersive interactive art installations and performances have now entered the public conversation, shaping the average audience experience. Emerging and innovative art forms existed before the pandemic, but they have assumed a deeper meaning and stronger presence after it. New art spaces have been explored, opening the horizon for a more inclusive, collective, and safe art experience.

The “Against the Current” exhibition at Art Windsor- Essex, realized in collaboration with the Moment Factory expertise, is an example of the potential interconnection between art institutions and the city. In the latest version of the project, which had a soft launch in March 2022, visitors could go on an interactive art walk using their smartphones connected to downtown Windsor’s free Wi-Fi. Using simple tools, such as QR codes and an App, visitors could interact with the nine art reproductions, access a map, and play mini-games designed to help them connect to and think about art in new ways.

This is one of many examples of the intersection between art and technology within a city space. Others worth including are the “Stolen Art Gallery” by Compass UOL VR immersive experience; the AI artist Sougwen Chung and her interest in human-machine collaboration; the computer software-based work of Refik Anadol or Quayola.

What role might these current and future artists play in creating digital immersive artworks in future cities?

Figure 1 - The “Against the Current” exhibition at Art Windsor- Essex, Canada.

What is a smart city?

It is important to understand what is defined today as a smart city and why it is becoming a predominant public concern. It is obvious that technology has filled in the gaps that could not previously be filled, such as unequal access to knowledge and a standard of living for all citizens.

The main driver of budding smart cities is the interconnectivity between all aspects of our lives which is possible thanks to new, disruptive technologies. Indeed, smart cities use data and digital technologies to make better decisions and enhance the quality of life. Agencies and municipalities are able to follow events as they develop, comprehend how demand patterns are evolving, and respond with quicker and more affordable solutions thanks to more complete, real-time data.

This conceptual framework is emerging at the intersection of urban planning, the internet of things (IoT), big data, information and communication technology (ICT), and informational urbanism. This last concept, according to Karolina Littwin and Wolfgang G. Stock, both professors at the Heinrich Heine University Düsseldorf in Germany, analyzes all facets of knowledge and information that have an impact on cities, their places, institutions, and—most importantly—their inhabitants. At the core of a smart city are information and communication technologies. However, what shouldn't be overlooked is knowledge in the form of tacit knowledge (tied to people) and explicit knowledge (bound to documents). According to Littwin and Stock’s approach, we can consider the city as a dynamic and complex system consisting of urban subsystems and within each of these, it is possible to identify aspects of creativity and art.

Another critical concept for smart cities is the “Array of Things” (AoT). This term defines the collaborative effort among different actors, such as government, universities, industry partners, community members, etc. to collect relevant data about the urban environment and activities for research and public use.

The city of Chicago provides an appropriate illustration of this concept. It aims to create a sustainable lifestyle based on IoT solutions and its AoT system made of urban sensing devices called “urban telescope.” Chicago is a pioneer in inclusivity and access of such data—citizens are encouraged to download the data for their own analysis and reflections. In this regard, DePaul University has recently developed “The Technology for Social Good Research and Design Lab,” a coalition of students and faculty who are interested in designing, building, and studying tools and technology to create, educate, and empower those they serve.

“The ability of cities now to draw a line between technology and data and real-world outcomes for communities is moving in the right direction.” (Lena Geraghty, Smart Cities Dive)

Smart Cities and Arts

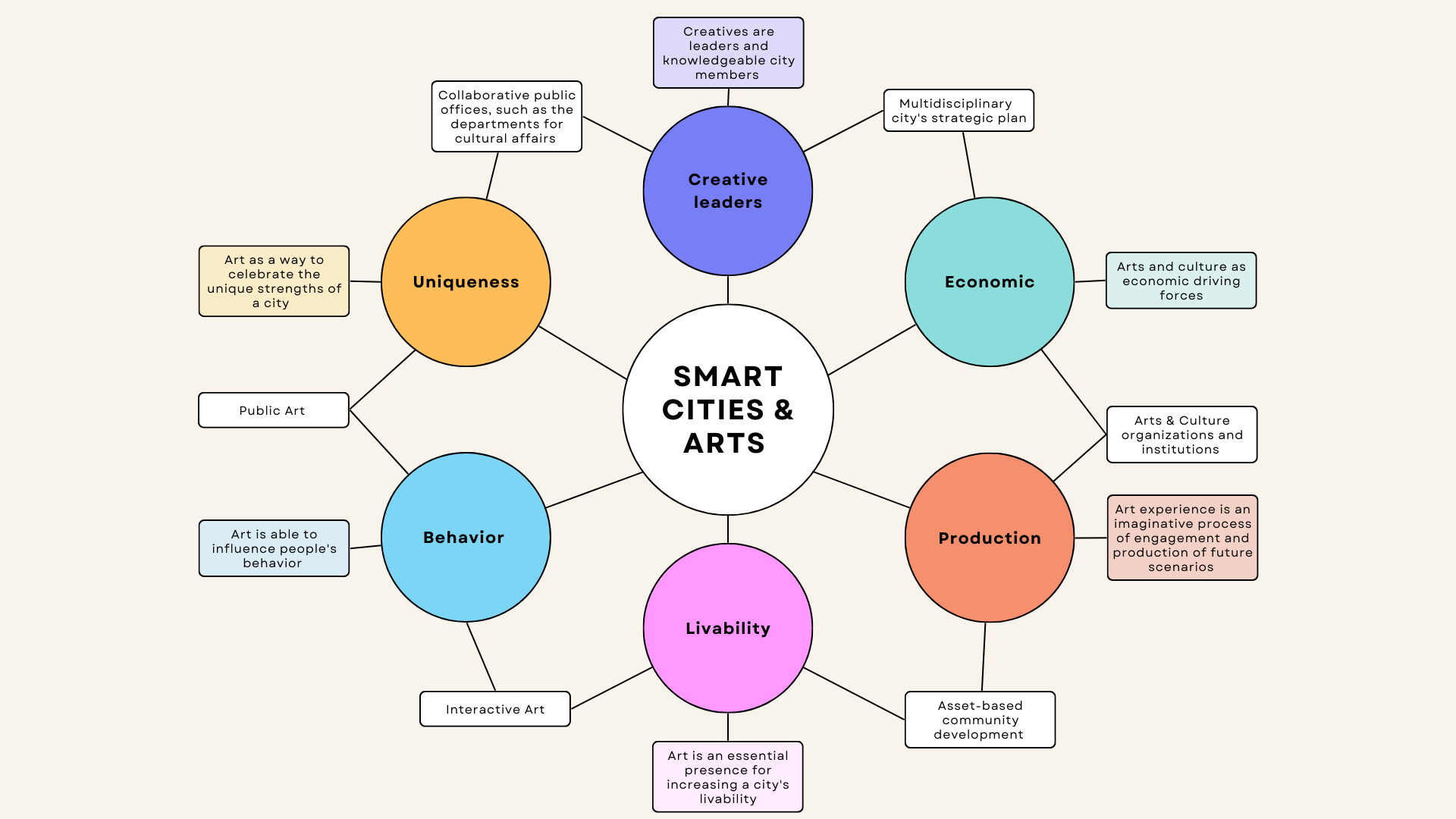

Figure 2: Infographic of the role of arts & culture in modern smart cities. Source: Author

The fact that contemporary art is increasingly permeated by technology has been established, as has the fact that the world is transitioning towards a smart ecosystem. But how do future art organizations interact and take part in shaping future smart cities? How will the aesthetic experience of art be considered a fundamental part of the transformation of cities into smart infrastructure?

First, municipal leaders are realizing that smart city strategies start with people, not technology. “Smartness” is not just about installing digital interfaces in traditional infrastructure or streamlining city operations, but it is also about using technology and data purposefully to make better decisions and deliver a better quality of life.

The creativity and the unique heritage of each city will be recognized as a source of growth, brand, and pride, and it will contribute to the urban well-being. It is in fact important to understand that increasing the functionality of a city does not inherently increase its value; on the contrary, technology can create standardized cities.

Art already serves our society in a distinctive way. Referring again to the urban subsystem defined by Littwin and Stock, it can be stated that digital art in public places is part of the city’s creative infrastructure as well as of the space of places. It influences people’s information behavior, and it has effects on the city’s knowledge-based and creative economy. According to Richard Florida, creativity is the driver of the twenty-first-century city and it is fundamental to attract members of the creative class in order to apply their knowledge in the city’s companies and administrations.

““Technology for smart cities without art and culture component will create lop-sided development only. Therefore, you need to take efforts to design, attract, retain and nurture the creative workforce of our cities. Technology and art and culture must embrace each other. We cannot have smart cities without art and culture.” ”

But this is not all, and art cannot only be valued for its instrumental or economic value. It is necessary to include the concept expressed by John Dewey in his “Art as Experience” (1934). Dewy discusses experiencing art as a reciprocal process that is imaginative: in our engagement with art, we experience the artwork, while the experience also produces us. Thus, the aesthetic experience is transformative and this mutual coming into existence is not a planned creation but insinuates an open future as well as an open past. He poetically inserts the engaging and transformative power of imagination in the production of futures, considering an aesthetic experience and the intrinsic individual impact of art as a potential producing force. Being able to have control over our future through engagement is a fundamental and rather complex task, but through this idea it is possible to cope with the deficit of a scientific and technological representation. With this, it is argued that both approaches are fundamental in order to involve multidisciplinary actors and develop the most effective process of imaging the future.

The future of art

This has been explored within the art community. The potential form of future art has been defined, by curator Jeffreen M Hayes, as more fluid, representative, and free of boundaries.

““In the year 2040, art might not look like art (unless it’s a painting), but it will look like everything else, reflecting zeitgeists as multitudinous and diverse as the artists themselves. There will be artist-activists leading political upheaval; there will be formal experimenters exploring new mediums and spaces (even in outer space), and there will be strong markets in Latin America, Asia and Africa. So, in the world of culture at least, the West may find itself playing catch up.” ”

Borjabad also theorizes that not only must the future be predicted, but that potentially multiple futures are to be expected. On this, Elizabeth Merritt in her article “How to Forecast the Future of Museums” goes beyond and explains that studying the future implicates considering things that can potentially change. Therefore, what we can do is imagine futures as a cone radiating outward from the present. This ‘‘cone of plausibility’’ defines futures that might reasonably occur, and it is defined by the limits of what is likely to happen.

Museums, such as The Smart Museum of Art at the University of Chicago and the New Museum in New York (and in particular its Incubator), are continuously involving an interdisciplinary mix of artists, designers, technologists, futurists, and creative entrepreneurs to create a conversation around the future of art, urban spaces and creative entrepreneurial projects. Moreover, and just to cite of few of them, research is currently engaging at the center of these conceits: The Center for the Future of Museums of the American Alliance of Museum organization; the Metro21: Smart Cities Institute of the Carnegie Mellon University; the smart cities and the role of their creative members by McKinsey and Company; the SmartCitiesWorld platform and specifically their Cultural Space page; etc. This is a clear sign that it is been recognized the importance of the debate about future scenarios and that arts and technology (within their relative evolution) are and must be deeply integrated to shape those scenarios.

Figure 3: Art on theMART, a permanent public art project in collaboration with the City of Chicago.

Smart cities do, and will, need art.

In conclusion, it has been argued that culture and the arts have different, essential, roles:

to celebrate the unique strengths of a city

an economic driving force

to influence people’s information behavior

an imaginative process of engagement and production of future scenarios

an essential presence for increasing a city’s livability

Creatives are leaders of the future city, as well as knowledgable city members. But arts are sometimes overlooked in discussions on the "smart" future of our urban environment. As managers of the arts, we must consider how the arts and their institutions fit into the discussion of the future of smart cities.

-

“A New VR Experience Takes You Into a Museum of Stolen Masterpieces.” Accessed September 27, 2022. https://hyperallergic.com/740555/a-new-vr-experience-takes-you-into-a-museum-of-stolen-masterpieces/.

Admin, C. T. I. “5 Elements in Smart Cities.” CTI, November 22, 2016. https://computradetech.com/blog/trends-and-solution/5-elements-in-smart-cities/.

Bertrand, Maglyn. “Immersive Experiences in Museums: A Look at Art Windsor-Essex’s ‘Against the Current.’” American Alliance of Museums (blog), July 1, 2022. https://www.aam-us.org/2022/07/01/immersive-experiences-in-museums-a-look-at-art-windsor-essexs-against-the-current/.

American Alliance of Museums. “Center for the Future of Museums.” Accessed September 27, 2022. https://www.aam-us.org/programs/center-for-the-future-of-museums/.

Smart Cities World. “Cultural Space.” Accessed September 25, 2022. https://www.smartcitiesworld.net/cultural-space/cultural-space.

Carnegie Mellon University. “Smart Infrastructure - Metro21: Smart Cities Institute - Carnegie Mellon University.” Accessed September 25, 2022. https://www.cmu.edu/metro21/projects/smart-infrastructure/index.html.

Dewey, John. Art as Experience. Perigee trade paperback edition. New York: Berkley Publishing Group, 2005.

“Imagining the Cities of the Future | McKinsey.” Accessed September 25, 2022. https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/public-and-social-sector/our-insights/thriving-amid-turbulence-imagining-the-cities-of-the-future.

American Alliance of Museums. “Immersive Experiences in Museums: A Look at Art Windsor-Essex’s ‘Against the Current,’” July 1, 2022. https://www.aam-us.org/2022/07/01/immersive-experiences-in-museums-a-look-at-art-windsor-essexs-against-the-current/.

“Info - Sougwen Chung (愫君).” Accessed September 27, 2022. https://sougwen.com/info.

Lab, Sensor. “The Role of the Digital Artist in the Smart City.” Sensor Lab (blog), June 17, 2019. https://medium.com/sensor-lab/the-role-of-the-digital-artist-in-the-smart-city-98c26335eec.

Lente, Harro van, and Peter Peters. “The Future as Aesthetic Experience: Imagination and Engagement in Future Studies.” European Journal of Futures Research 10, no. 1 (December 2022): 16. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40309-022-00204-8.

Littwin, Karolina, and Wolfgang G. Stock. “Signaling Smartness: Smart Cities and Digital Art in Public Spaces.” Journal of Information Science Theory and Practice 8, no. 1 (March 30, 2020): 20–32. https://doi.org/10.1633/JISTAP.2020.8.1.2.

Maldonado, Devon Van Houten. “What Will Art Look like in 20 Years?” Accessed September 25, 2022. https://www.bbc.com/culture/article/20190418-what-will-art-look-like-in-20-years.

Merritt, Elizabeth. “How to Forecast the Future of Museums.” Curator: The Museum Journal 54, no. 1 (2011): 25–34. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2151-6952.2010.00062.x.

NEW INC. “NEW INC.” Accessed September 27, 2022. https://www.newinc.org.

“New Museum.” Accessed September 27, 2022. http://www.newmuseum.org/.

Quayola. “Quayola.” Accessed September 27, 2022. https://quayola.com/.

Refik Anadol. “Refik Anadol / Media Artist + Director.” Accessed September 27, 2022. https://refikanadol.com/.

Roy, Gopanjali. “Smart Cities Project Need Inclusion of Art and Culture.” Media India Group (blog), January 2, 2017. https://mediaindia.eu/culture/smart-cities-project-need-inclusion-of-art-and-culture/.

Schilke, Charles Noel. “Raising the IQ of Smart Cities: Chicago’s ‘Array of Things’ Urban Data Device.” Real Estate Issues, Spring 2017, 69–74.

“Smart Cities Project Need Inclusion of Art and Culture - Media India Group.” Accessed September 27, 2022. https://mediaindia.eu/culture/smart-cities-project-need-inclusion-of-art-and-culture/.

“Smart Museum of Art | The University of Chicago.” Accessed September 27, 2022. https://smartmuseum.uchicago.edu/.

“Understanding Equity and Diversity in Smart City Infrastructures: Chicago, IL, USA: XRDS: Crossroads, The ACM Magazine for Students: Vol 28, No 3.” Accessed October 24, 2022. https://dl.acm.org/doi/abs/10.1145/3522697.

Smart Cities Dive. “With IT Modernization Plan, Chicago Aims for More Accessible, Transparent and Secure Data.” Accessed October 24, 2022. https://www.smartcitiesdive.com/news/chicago-technology-it-modernization-plan-digital-service/627078/.

Wiener, Anna. “The Rise of ‘Immersive’ Art.” The New Yorker, February 10, 2022. https://www.newyorker.com/news/letter-from-silicon-valley/the-rise-and-rise-of-immersive-art.

Wilson, Ryan. “Interconnectivity: The Backbone of Budding Smart Cities.” BuiltWorlds. Accessed September 25, 2022. https://builtworlds.com/news/interconnectivity-backbone-budding-smart-cities/.

Yildiz, Dr Mehmet. “What Does It Take To Be A Smart City?” Technology Hits (blog), June 2, 2022. https://medium.com/technology-hits/what-does-it-take-to-be-a-smart-city-95b23df0f61c.