By: Alexander Farrell

As virtual, augmented, and mixed reality technologies merge with AI-driven platforms, the line between physical and digital life is rapidly disappearing. In these immersive environments, questions of ethics, accountability, and safety have become increasingly urgent.

While XR (extended reality) has applications–from education and healthcare to architecture and live performance–gaming remains its dominant domain. According to Statista, the global XR gaming market is projected to exceed $520 billion by 2025, with immersive gaming driving over one-third of all XR revenue worldwide. As this sector grows (expected to reach $730 billion globally by 2030), its cultural and behavioral norms will shape not only how people play, but also how they socialize across virtual worlds.

Virtual harm–harassment, sexual violence, manipulation, or misinformation–may occur through avatars or interfaces, but its effects are real. Victims report trauma, stigma, and financial loss, while law enforcement and policymakers struggle to define responsibility in these spaces.

This article asks: What can past incidents of online harm teach us, and how can existing safety frameworks guide the ethical and legal responsibilities of AI-driven immersive platforms today?

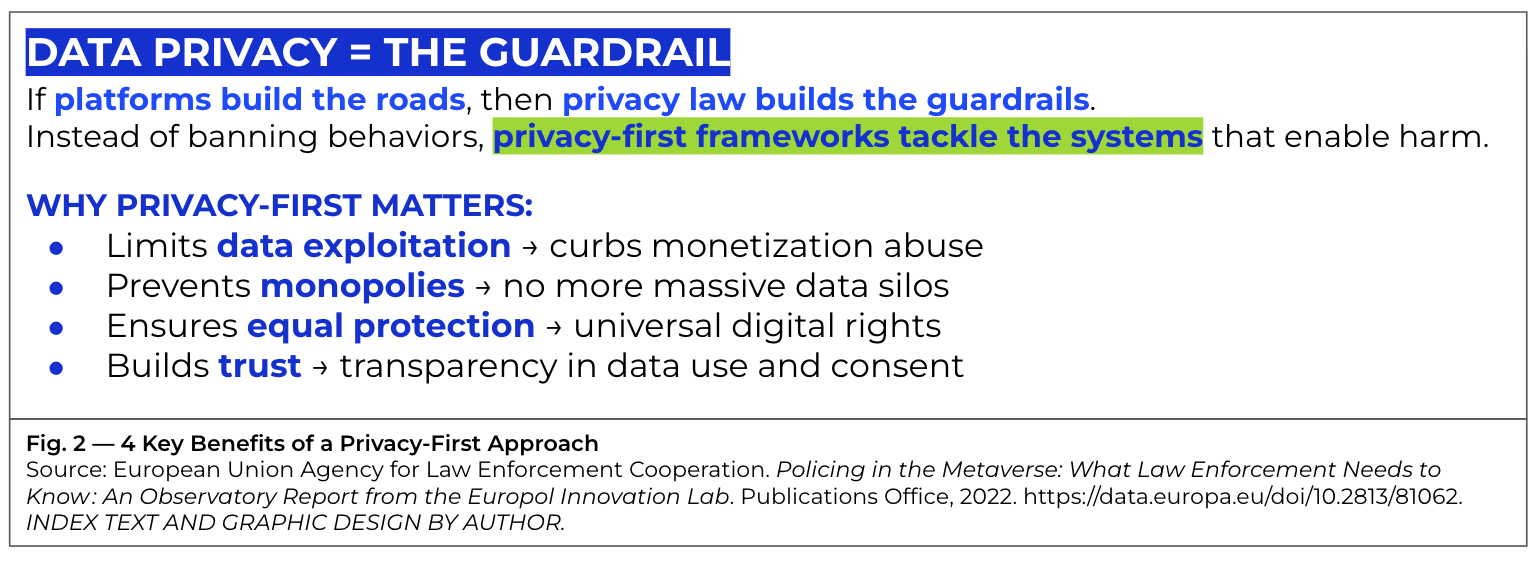

The argument is simple: as platforms build the digital roads where billions now interact, they must also install guardrails–systems of prevention, accountability, and repair. Achieving this requires a shared language for harm, strong data privacy laws that limit exploitation, and safety-centered design that treats digital well-being as a core principle, not a policy afterthought.

A History of Virtual Harm

Online harm has existed since the start of online interaction. In the early 1990s, text-based multi-user domains (MUDs) recorded the first cases of virtual sexual assault, where users’ avatars were manipulated without consent. Victims described emotional responses similar to real-world assault.

As environments evolved, so did harm. In Second Life (2007), a case in Brussels involving avatar manipulation sparked debate over “virtual rape.” Because no physical contact occurred, the law could not categorize it as a crime–but the ethical implications endured.

In 2021, a user in Meta’s Horizon Worlds reported being “virtually gang-raped” by multiple avatars. A 2024 Washington Post report found that nearly half of women using VR have experienced harassment, worsened by immersive features like haptic feedback and spatial audio. In QuiVr, an archery game, a player reported feeling physically violated when her avatar was groped in real time–showing that embodiment in VR magnifies emotional and psychological effects far beyond traditional gaming.

Beyond sexual violence, platforms have faced legal scrutiny for child exploitation and data misuse. In 2023, families sued Roblox for enabling and profiting from the sexual exploitation of minors, highlighting the conflict between innovation, profit, and accountability. Even as Epic Games’ Fortnite and Roblox experiment with live concerts and creative “metaverse” performances, these same interactive affordances create new vulnerabilities for both performers and audiences.

From early forums to the metaverse, these incidents show a clear pattern: technology evolves faster than the rules meant to govern it. What was once “bad online behavior” is now a question of digital rights and governance.

The Legal Lag

Legal systems remain unprepared for virtual harm. Attorney TJ Grimaldi notes three major challenges:

Avatars lack legal personhood, leaving no recognized victim or perpetrator.

Most laws require physical contact to define assault or battery.

Jurisdiction is unclear across international servers and platforms.

Even Europol’s Innovation Lab has warned that policing virtual environments requires new models of cooperation and evidence collection. For now, accountability depends on corporate policy, not public law.

This gap is particularly stark in XR gaming and performance spaces, where audience interactions can blur boundaries between play and harassment. For instance, in live VR concerts or immersive theater experiences, audience members can often approach, gesture toward, or even “touch” performers’ avatars–raising new ethical questions about spectator behavior and consent in digital performance.

Defining Digital Harm: From Concept to Framework

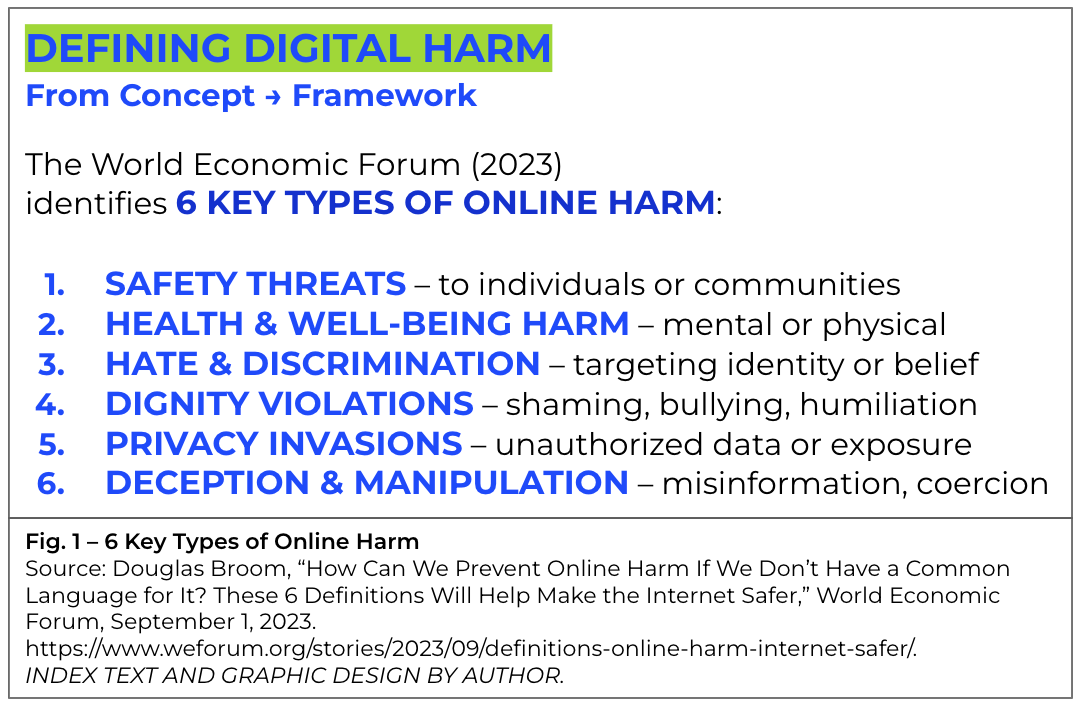

When law lags behind technology, language must lead. The World Economic Forum’s 2023 Global Coalition for Digital Safety proposed six categories of online harm:

Threats to personal and community safety

Harm to health and well-being

Hate and discrimination

Violation of dignity

Invasion of privacy

Deception and manipulation

This framework aims to align global standards before legislation. Without shared definitions, policymakers risk inconsistent, reactionary responses.

Researchers echo this need. In 2025, “A User-Centric Taxonomy of Cyber Harm in the Metaverse” defined digital harm as “negative physical or mental effects directly linked to online activity,” shifting focus from technology to human impact. Naming harm makes it visible–and therefore actionable.

In XR gaming, these categories appear in tangible form: proximity-based harassment, hate speech over spatial audio, or manipulative in-game economies that exploit user psychology. In VR performance, harm can also occur when audience members violate the “fourth wall,” entering virtual stages, shouting over performers, or recording without consent–actions that demand new codes of conduct.

Platforms as Builders of Digital Roads

Digital platforms function like infrastructure. Meta, Roblox, and Epic Games build the routes through which users move, interact, and create. Yet unlike physical roads, these spaces often lack guardrails. Safety features appear reactively–after public backlash.

The Electronic Frontier Foundation calls this the “whack-a-mole” model of governance: reactive measures focused on symptoms rather than systems. Most harm stems not from user behavior, but from profit-driven design choices that prioritize engagement, data collection, and frictionless sharing–even when these enable abuse.

Consider VRChat or Rec Room: both have introduced “personal boundary” settings only after widespread reports of avatar harassment. In Fortnite’s “Festival” mode (a social-music crossover space), Epic has faced criticism for lacking clear moderation during live events. These examples show how reactive safety design lags behind user innovation, echoing the EFF’s critique of policy-by-crisis.

Policymakers, in other words, are responding to the loudest crisis of the week while the larger architecture of exploitation remains untouched.

The Surveillance Engine

At the root of most digital harm is data extraction.

Immersive platforms record eye movements, speech, heart rate, and inferred emotions to fuel targeted advertising. This system rewards manipulation and polarization. The EFF’s Privacy First report argues that surveillance-based business models are the foundation of online harm.

In gaming, this extraction is often disguised as personalization: adaptive difficulty, emotion-driven NPC responses, or “heat maps” that study gaze and reaction. Yet the same data can reveal intimate behavioral signatures, turning play into a form of biometric surveillance. In performance contexts, audience gaze and reaction data–marketed as “engagement metrics”– risk commodifying attention itself.

A privacy-first framework treats safety as a design principle. Limiting data collection reduces opportunities for abuse. Restricting manipulative advertising realigns incentives with user well-being. Privacy is not just secrecy–it is about power: who controls data, who profits, and who bears the cost when it is misused.

Data Privacy as the Guardrail

If platforms build the roads, privacy law builds the guardrails. Instead of banning behaviors, comprehensive privacy legislation addresses structural incentives that enable harm.

A privacy-first approach offers four key benefits:

Reduces exploitation by limiting data monetization.

Weakens monopolies by preventing massive data silos.

Protects all users equally through universal rights.

Builds trust by clarifying data use and consent.

The EU’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) is a starting point, but immersive technologies require expanded protection for biometric and behavioral data like gaze tracking, gesture patterns, and emotional inference. For example, VR headsets now collect micro-movements and pupil dilation that can reveal stress, attraction, or fatigue–information that must not be commercialized or shared without explicit consent. Policies grounded in privacy make systems safer by design, not restriction.

Coordinating Global Action

Digital platforms cross borders; governance must too. The World Economic Forum’s coalition shows how governments, companies, and civil society can coordinate standards. Shared definitions and enforcement prevent “regulatory arbitrage,” where companies relocate to weaker jurisdictions.

A global privacy framework (like climate accords) could align incentives toward sustainability rather than profit. As immersive platforms merge with AI, such cooperation is essential for a trustworthy digital future. Given XR’s projected annual growth rate of 28% through 2030, a unified framework would prevent a patchwork of local laws from undermining collective safety efforts.

Building the Future Responsibly

The next generation of culture and human connection will unfold in immersive digital spaces. These technologies offer extraordinary creative potential–but only if users feel safe and in control.

Ethics cannot be added later. Safety must be built in from the start–through design, policy, and education. Treating virtual harm with the same seriousness as physical harm affirms a shared commitment to dignity and accountability.

For the gaming industry, this means embedding safety features as core gameplay infrastructure, not optional add-ons. For performance and live audience XR spaces, it means rethinking spectatorship itself: building consent systems, behavioral norms, and privacy zones that recognize digital embodiment as an extension of physical presence.

Comprehensive privacy legislation is more than reform; it is a moral commitment to human rights in the digital age. Just as seatbelts and traffic laws made modern transportation safe, privacy-first guardrails will determine whether immersive technology empowers or exploits.

The digital roads are already under construction. The question is whether we will build them safely.

-

Adhanom, Isayas Berhe, Paul MacNeilage, and Eelke Folmer. “Eye Tracking in Virtual Reality: A Broad Review of Applications and Challenges.” Virtual Reality 27, no. 2 (2023): 1481–505. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10055-022-00738-z.

Belamire, Jordan. “My First Virtual Reality Groping.” Athena Talks, October 22, 2016. https://medium.com/athena-talks/my-first-virtual-reality-sexual-assault-2330410b62ee.

Broom, Douglas. “How Can We Prevent Online Harm If We Don’t Have a Common Language for It? These 6 Definitions Will Help Make the Internet Safer.” World Economic Forum, September 1, 2023. https://www.weforum.org/stories/2023/09/definitions-online-harm-internet-safer/.

Chalmers, David. “What Should Be Considered a Crime in the Metaverse?” Tags. Wired, n.d. Accessed September 23, 2025. https://www.wired.com/story/crime-metaverse-virtual-reality/.

European Union Agency for Law Enforcement Cooperation. Policing in the Metaverse: What Law Enforcement Needs to Know : An Observatory Report from the Europol Innovation Lab. Publications Office, 2022. https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2813/81062.

Fleck, Anna. “Infographic: The World’s Top Gaming Markets.” Statista Daily Data, August 20, 2025. https://www.statista.com/chart/25593/biggest-video-game-markets.

Grimaldi, TJ. “Can You Get Arrested for What You Do In Virtual Reality?” TJ Grimaldi, January 9, 2024. https://tjgrimaldi.com/can-you-get-arrested-for-what-you-do-in-virtual-reality/.

Ingram, Michael Brandon. “Fortnite Ramping Up Moderation on New Game Mode.” Game Rant, September 21, 2025. https://gamerant.com/fortnite-ramping-moderation-bans-delulu-game-mode/.

Luck, Morgan. “The Gamer?S Dilemma: An Analysis of the Arguments for the Moral Distinction Between Virtual Murder and Virtual Paedophilia.” Ethics and Information Technology 11, no. 1 (2009): 31–36. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10676-008-9168-4.

Lynn, Regina. “Virtual Rape Is Traumatic, but Is It a Crime?” Tags. Wired, n.d. Accessed September 25, 2025. https://www.wired.com/2007/05/sexdrive-0504/.

McSherry, Corynne, Mario Trujillo, Cindy Cohn, and Thorin Klosowski. “Privacy First: A Better Way to Address Online Harms.” Electronic Frontier Foundation, November 14, 2023. https://www.eff.org/wp/privacy-first-better-way-address-online-harms.

“Multiple Families Sue Roblox Corporation for Exploiting Children Online.” Business Wire, November 7, 2023. https://www.businesswire.com/news/home/20231107766120/en/Multiple-Families-Sue-Roblox-Corporation-for-Exploiting-Children-Online.

Nix, Naomi. “Attacks in the Metaverse Are Booming. Police Are Starting to Pay Attention.” The Washington Post, February 4, 2024. https://www.washingtonpost.com/technology/2024/02/04/metaverse-sexual-assault-prosecution/.

Robertson, Adi. “Meta Is Adding a ‘Personal Boundary’ to VR Avatars to Stop Harassment.” The Verge, February 4, 2022. https://www.theverge.com/2022/2/4/22917722/meta-horizon-worlds-venues-metaverse-harassment-groping-personal-boundary-feature.

Sander, Melissa Mary Fenech. “Questions about Accountability and Illegality of Virtual Rape.” Master of Science, Iowa State University, Digital Repository, 2009. https://doi.org/10.31274/etd-180810-1515.

Smith, Adam. “Rape in Virtual Reality: How to Police the Metaverse | Context by TRF.” Accessed September 25, 2025. https://www.context.news/digital-rights/sex-assault-claims-and-crime-raise-fears-of-new-virtual-wild-west.

Statista. “Games – Worldwide”. 2025. Statista.

Tennant, Zanna. “I Don’t Know What to Tell You. It’s the Metaverse—I’ll Do What I Want.” How Rape Culture Pervades Virtual Reality | LawSci Forum. April 17, 2022. https://mjlst.lib.umn.edu/2022/04/17/i-dont-know-what-to-tell-you-its-the-metaverse-ill-do-what-i-want-how-rape-culture-pervades-virtual-reality/.

Webb, Jeb, Sophie McKenzie, Robin Doss, Radhika Gorur, Graeme Pye, and William Yeoh. “A User-Centric Taxonomy of Cyber Harm in the Metaverse.” International Journal of Law, Crime and Justice 81 (June 2025): 100734. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijlcj.2025.100734.