By: Noel Reed

The digital art market

The advent of the internet enabled artists to create niche markets in which their particular styles could be shared, sold, and consumed across multiple platforms and in multiple mediums. “Digital art” can encompass a vast array of things, from logos for corporations to installation pieces with digital components. Within this network, there is a whole world of natively digital artists; artists that create their pieces with digital software, upload it onto the internet for consumption, and accept commissions across a variety of social and e-commerce platforms.

The internet has enabled freelance artists to sustain full-time careers creating commission-based work for individual buyers, instead of contracting with businesses and institutions exclusively (Cant 2023). This has created a viable path in which artists have more control over their creative output, as commission contracts from individual buyers are negotiated between buyer and seller only, and not a workforce with competing interests. Artists are encouraged to keep an up-to-date portfolio of non-commissioned original work to advertise their illustration styles, meaning individual buyers usually approach an artist because their specific style and artistic subjects are appealing (Cant 2023).

A primer on furries

One of the most robust digital art communities is furries, whose “fursonas” (anthropomorphic personas) are mainly expressed through digital 2D art and “fursuits.” Furries’ main community venues exist online across many platforms, with conventions held annually in many cities to bring together internet-based friendships. The community is huge and ever-expanding – this past summer, in 2025, Pittsburgh’s Anthrocon attracted 19,000 attendees, bringing the city an estimated $21 million in tourism revenue (Riley 2025).

What is striking about the furry fandom, and why digital art is so relevant to them, is their decentralized and participatory nature: “[the furry fandom is] a conglomerate of artists, writers, costumers, musicians, and fans who congregate and collectively contribute content to the fandom: more than half of furries do some form of graphic art or creative writing, meaning the fandom is filled with thousands of unique content creators. This is one of the traits that makes it far more participatory than other fan communities—rather than passively consuming content, many furries actively contribute content” (Aaron 2017). Because there is no single piece of media that the community shares, it is instead a communal world-building exercise expressed in creative mediums.

Because of the vastness of the furry network and its relative obscurity, it is hard to find hard figures on just how much revenue is generated by furry art commissions and trades. But the popularity of new media (video and digital art) in the online market is on the rise–from 2020 to 2022, the share of new media sales rose from 17% to 37%, a 20% increase (Statista 2022). Furry art is purchased and sold on larger platforms such as Bluesky, Etsy, and DeviantArt, as well as more niche platforms like FurAffinity, itaku.ee, and Weasyl. Many transactions happen between friends on private Discord and Telegram servers. There is a general consensus that furries provide a stable source of income to independent digital artists – one illustrator, Amber Hill, says that “When I accept new work, [furry art is] usually about a quarter to a half of my income…enough to support my mortgage habit, ha-ha” (Feldman 2016).

To better understand the experiences of digital furry artists in web2.5, I had the pleasure of meeting with two independent artists, Feer and Caim; and one furry art collector, Stella. Feer and Caim have both drawn digital furry art for over 10 years, and have worked full-time as independent artists at various points in time. Both expressed that the furry community was in a period of flux as the internet shifted from blog-like, niche platforms (Tumblr, DeviantArt, FurAffinity, etc.) to broader, algorithmic social media platforms (X, Bluesky, TikTok, etc.) (Caim and Feer 2025). Platforms like DeviantArt have seen a dramatic decline in senior artists (those posting before 2022) after the generative AI boom, and this shift is felt by the slow movement of digital artists to multi-use social platforms (Porres and Gomez-Villa 2024).

Figure 1: Feerwave (2023) by Feer. Source: Gallery | FEER.

Caim and Feer expressed a sense of fragmentation creeping into the community, as different furries devoted themselves to different platforms and thus engaged with only a subset of the broader community (Caim and Feer 2025). Feer established their initial client base on Twitter (now known as X) before moving their operations mainly to Bluesky and Telegram. Although he still has many repeat clients from Twitter, he says it’s more important now to establish client connections at in-person events like conventions and to be at least somewhat tapped into multiple social media platforms to avoid pigeonholing oneself into a platform that will inevitably become obsolete (Caim and Feer 2025).

Stella, the furry art collector, maintains there’s still a strong sense of centrality in the furry community: “There’s a very open understanding of what the going rate is for a certain character [from a certain, well-known artist]…Furry is a discerning audience. No one has ever strung those words together, but it’s true…it’s about art ownership from specific artists in a very kind of ancient ‘the same as it ever was’ [way],” likening the collection of furry art to the collection of high art from established artists (Stella 2025).

Problems facing digital art: easy replication, unclear ownership

An issue inherent to digital art is its lack of authentication (Tokranova and Bauters 2025, 3). Digital art, by its nature, is very easy to duplicate, as it exists as a file that people are able to endlessly download and replicate. This is reflected in the modest price tag of most digital art pieces: conventional routes of digital art sales include Etsy, DeviantArt, Shutterstock, and print-on-demand services like Society6, where artists earn only a percentage of their sales, the lowest being around 10% (Tokranova and Bauters 2025, 3). It has historically been an issue for digitally native artists to defend their work against replication, as the vastness of the internet makes perfect moderation nearly impossible. Most commission-based artists lack a robust, formal ownership defense structure for their art due to the already modest prices of their work versus the costs of legal safeguarding (like copyright or legal representation).

Non-fungible tokens (NFTs) have been proposed as a possible solution to digital art’s lack of provenance (Kartasheva and Trubina 2024). NFTs function by giving digital assets a certificate of authenticity stored on a blockchain, making interchangeability of the asset impossible (Lessard). NFTs are not the image itself but rather a data block containing the certificate of authenticity and anonymized transaction histories, in the same way a cryptocurrency blockchain stores currency transactions (Lessard). Proponents of NFTs argue that they have the potential to place digital art on the same playing field as more conventional art markets by assigning value to digital assets. They also give artists a higher level of independence from established institutions (Kartasheva and Trubina 2024, 3). Sale of digital assets is simplified by minting an NFT, as publishing and protecting your work online becomes a one-step process: mint the NFT, and you automatically have a certificate of authenticity (provenance) and a marketplace to sell your piece (profit).

However, an NFT does not automatically codify copyright ownership. A “smart contract” can be added to an NFT transaction that details the transference of a copyright from seller to buyer, but without these smart contracts, NFT art assumes the default copyright framework of visual art (Weiss and Özer 2022). The upside to NFTs and copyright maintenance is that instead of scouring the entire internet for infringement, “the search is limited to the blockchain…with a more focused strategy, we’ve turned the ‘sea’ into a ‘pond’ for identifying stolen images” (Weiss and Özer 2022). Other blockchain technologies, like cryptocurrency, offer artists decentralized banking while also safeguarding artists from chargebacks by having transactions documented (Soatok 2021).

In order to better understand the use-case of NFTs in the digital art market, I looked to the furry community as my case study. My reasons for specifically focusing on furries are numerous:

They are a large community (r/furry on Reddit boasts 172K members), where digital art is ubiquitous to community experience.

Almost all of that digital art is commissioned work from independent artists, as furries are not centered around content from large, professionalized corporations like movie studios (“6.1 Prevalence”);

Their multi-platform, intense involvement is a display of the potential of internet-based community building (Stella 2025);

My ability to speak with furry artists enabled me to answer my central question: Do NFTs and blockchain technology appeal to independent digital artists?

Furries and NFTs: trustful versus trustless

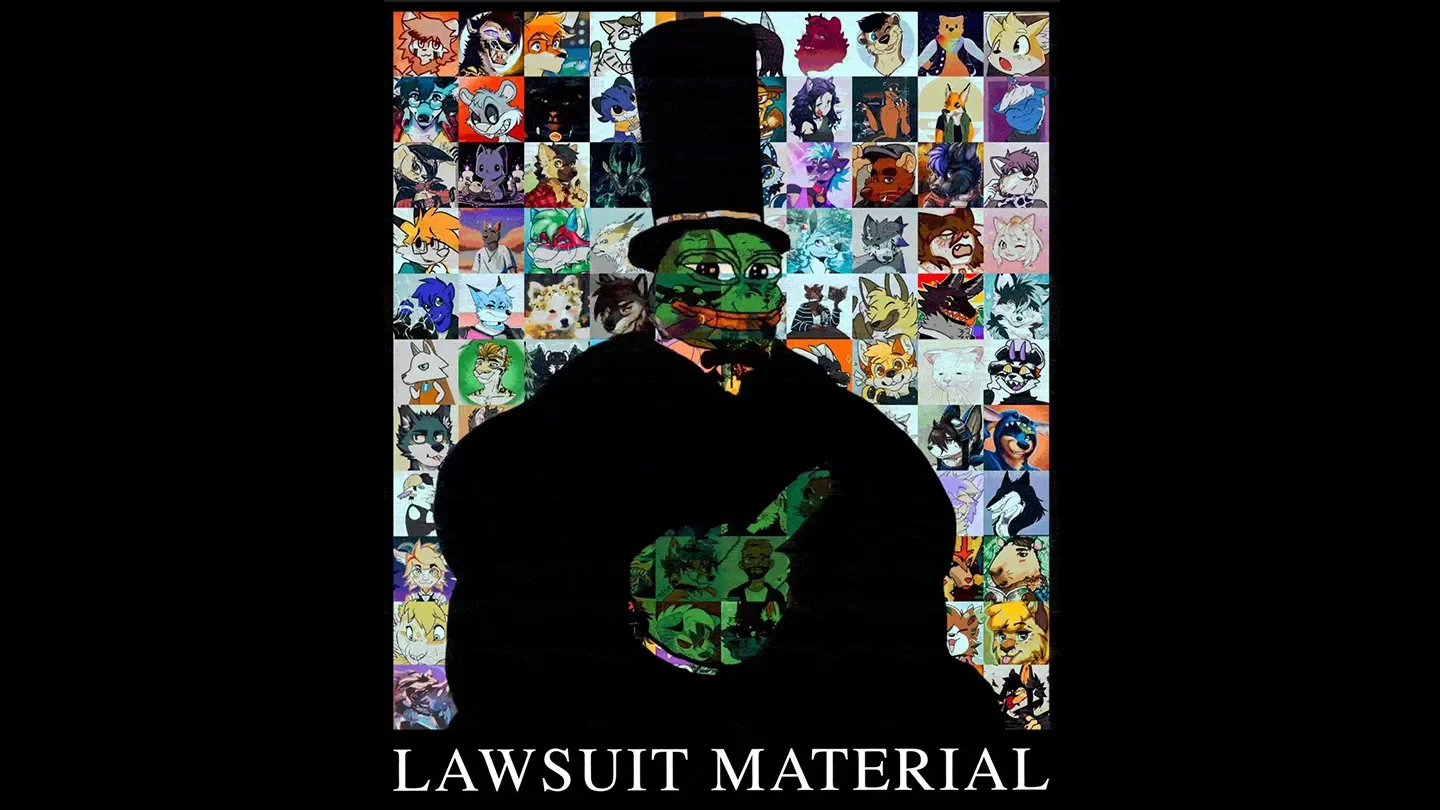

Furries’ relationship to NFTs and other web3 technologies has been, to put it tactfully, complicated. During the NFT boom of 2021, the general consensus among furries was that NFTs were at best a fad and at worst a threat. The most stark case of hostility between cryptofans and furries was the minting of the NFT “Right Click Save This” by NFT collector VincentVanDough (Ongweso 2021). “Right Click Save This” depicts Pepe the Frog overlaid on many small images of fursonas, raising his middle finger to his audience. Underneath the image are the captions “LAWSUIT MATERIAL” and “CALL: 1800-SUE-ME.” This NFT was in response to “right-click” discourse–skeptics of NFTs, many of whom were furries, pointed out that buyers were shelling out thousands of dollars for images that could be right-clicked and saved on anyone’s computer (Ongweso 2021). Creator VincentVanDough stole skeptics’ profile pictures depicting their fursonas to use as the backdrop of the NFT image, challenging them to prove their ownership of the images without the use of the blockchain. In retaliation, the implicated furries filed a Digital Millennium Copyright Act (DMCA) violation report and got the NFT taken off its platform, but not before it sold for $94,000 (Ongweso 2021).

Figure 2: “Right Click Save This” by VincentVanDough. Source: Vice Media.

Some furries did recognize the potential use-case for blockchain technologies. In considering the potentials for cryptocurrencies in furry art transactions, the blog Dogpatch Press mused that cryptocurrencies could potentially block buyers from winning auctions without paying in full, add market mediation to the subculture otherwise hard to acquire, and protect furries from censorship due to their decentralized nature (Dogpatch Press 2020). Most others, though, argue the use of NFTs is unnecessary in the furry community because of the foundation the community is built on: trust.

“Digital communities based on interdependence tend to build long-lasting bonds and stick together through tribulations,” writes cyberethnographer Ruby Justice Thelot. “The furries have persevered through digital transformations, scandals, and internal conflicts — and their story is a reminder that most human interactions still require trust. This is especially important when it comes to art, which is a particularly relational practice” (Thelot 2023). Through this people-first approach, furries have constructed a complex network of community governance that shields artists from having their work traced, copied, or claimed by the non-buyer.

“These characters [fursonas] are really connected to individual people, and those people are real… these people interact with people online, they use these characters as their icons on forums, on Twitter, on Tumblr, and people know who they are, and I think that’s a real aspect that is probably super unique” explains Stella, the furry art collector (Stella 2025). Because of this very personal identification with the characters depicted in furry art, members of the community are able to recognize when someone is falsely claiming a character as their own or directly stealing aspects from others’ artwork. Somewhere along the degrees of separation, these people know each other as these characters. As such, they are very resistant to the idea that the furry community should be profitable in the way conventional NFTs could be: “They fear the market being saturated by soulless token trades, and drowning out the healthy sharing of unique stories, characters, and creativity. It could seem disheartening that genuine care might turn to greed, and kill the joy that a commission brings to both recipient and creator” (Dogpatch Press 2021).

What struck me most in my research is just how robust the archive of fursona ownership and artists’ styles was, despite furries’ decentralized nature as an underground affinity group. Some examples of community moderation and archiving include the Fursuit Database, dating back to 2005; Toyhouse; and Furarchiver.

Along with these more formal resources, the community members I spoke to repeatedly referred to the implicit social rules that upheld provenance and a respect for people’s original content. “I haven’t ever been too worried about people ripping stuff. Like, it’s not really an issue that I’ve ever encountered…” says Caim, while Feer clarified the general expectation of how the community handles art stealing: “[people in the community will] alert [the artists they know], you know, they’re the people that like their stuff and that are fans of them. They’ll be like, ‘Hey, this person’s replicated my stuff or just taking my art and putting it on whatever, don’t buy from them. And also, could you contribute to filing takedowns for this just to get more eyes on it faster?’” (Caim and Feer 2025). There is a very low tolerance for anyone stealing someone’s character, and those who steal are swiftly broadcasted on public platforms. This form of community governance seems in itself a sort of analog blockchain, what Stella called an “oral history” of ownership and furry scandal (Stella 2025).

Figure 3: Swat away the flies! (2022) by Caim. Source: BlueSky.

This still, however, made me wonder if furry digital artists would ever consider NFTs as a digitally native tool to protect their assets against outsider infringement. I posed a question to Feer and Caim: imagine web3 has completely taken hold, and there is little to no way to escape AI algorithms from combing through your art to train their generative content – would NFTs be accepted then? They did not seem anxious about people or programs stealing their art, especially because they perceived furry art to be unprofitable in conventional marketplaces. Though, they acknowledge some of their friends have already been devastated by their styles showing up in generative content. Some have begun using programs like Glaze and Nightshade to make their visual content incomprehensible to AI models (Caim and Feer 2025).

Overall, then, there is great resistance to the adoption of blockchain technologies by furries because of three reasons: 1. Furries feel it is not in their interest or ethos to commercialize their community, and see NFT minting as one step too far; 2. Their reliance on community governance and trust doesn’t align with the trustless nature of the blockchain; and 3. Other confounding factors – like the environmental impacts of blockchain data centers – dissuade this socially conscious subculture (Lee 2022).

Still, it remains to be seen how blockchain technologies and the furry community, both of which are ever-expanding, change in the coming years. Ruby Justice Thelot asks if the crypto community can learn from the furry community as “The concept of a ‘trustless’ system implies a group of lone agents interacting with one another…Unlike communities where the deterrents are social, trustless communities embed the deterrents within their infrastructure, eschewing the difficulty and messiness of human cooperation and its shadow, conflict” (Thelot 2023). By not adding the human component to blockchain transactions, there is little room for error on part of the consumer – you cannot go back, so you cannot refute charges. If little Johnny somehow gets a hold of your cryptowallet, there’s no returning the NFTs of pixel art he bought on OpenSea. But if he were to use your credit card to commission a furry artist, there is room for negotiation.

“How might we use ‘trustless’ tools to foster in communities a greater degree of trust?” Thelot ends their piece with, arguing that if the blockchain is truly interested in bettering society by securing transactions, there must be some infrastructure to consider the people behind every block (Thelot 2023). This should be a question every cryptographer must reckon with: How do you apply such tools in a way that foster cooperation among agents, rather than devolving into a tribal mindset? If decentralization and democratization is the true goal of the blockchain, maybe developers should reckon with how a people-centered approach can maintain a low barrier of entry, thus minimizing the risk of centralizing forces. Maybe, just maybe, this lesson can be learned from studying the 50-year history of the furry subculture.

-

Aaron, Michael. 2017. “More Than Just a Pretty Face: Unmasking Furry Fandom.” Psychology Today, May 12.

https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/standard-deviations/201705/more-than-just-a-pretty-face-unmasking-furry-fandom.Caim, and Feer. 2025. Virtual interview with the author, October 6. Transcript available upon request.

Cant, Christopher. 2023. “Does Digital Art Sell, and How Much Does It Sell For?” SelfEmployedArtist, December 1.

https://www.christophercant.com/blog/does-digital-art-sell.Cant, Christopher. 2023. “What Is a Freelance Artist?” SelfEmployedArtist, December 1.

https://www.christophercant.com/blog/what-is-a-freelance-artist.Dogpatch Press. 2019. “Debunking Furry Misconceptions about Copyright—Guest Post by Grubbs Grizzly.” June 28.

https://dogpatch.press/2019/06/28/misconceptions-copyright-grubbs-grizzly/.Dogpatch Press. 2020. “The Dealers Den Plans to Rebuild with Unprecedented Features and Blockchain Technology.” October 15.

https://dogpatch.press/2020/10/15/the-dealers-den-rebuild/.Dogpatch Press. 2021. “NFTs Bring Hype, Greed, and Fraud; Creativity Will Suffer, Says Guest Writer Doppelfoxx.” December 22.

https://dogpatch.press/2021/12/22/nfts-hype-greed-fraud/.Feldman, Brian. 2016. “The Secret Furry Patrons Keeping Indie Artists Afloat.” Intelligencer, August 24.

https://nymag.com/intelligencer/2016/08/the-secret-furry-patrons-keeping-indie-artists-afloat.html.Furscience. n.d. “6.1 Prevalence.”

https://furscience.com/research-findings/artists-and-writers/6-1-prevalence/.Kartasheva, Anna A., and Marya A. Trubina. 2024. “Between Crypto Art and Copyright: NFT Tokens as Tools for Confirming the Authenticity of Art Objects.” Changing Societies and Personalities 8 (2): 508–25.

https://doi.org/10.15826/csp.2024.8.2.285.Lee, Swann Adara. 2022. “NFTs Are Temporary, Freelance Artists Reign Eternal.” Medium, February 28.

https://swannscribe.medium.com/nfts-are-temporary-freelance-artists-are-eternal-d35865157737.Lessard, Bianca. n.d. “NFTs, Minting, and Copyright: What You Should Know as an Artist.” Renno Co.

https://www.rennoco.com/blog/nfts-minting-and-copyright-what-you-should-know-as-an-artist.Ongweso Jr., Edward. 2021. “NFT Collector Sells People’s Fursonas for $100K in Right-Click Mindset War.” Vice, November 18.

https://www.vice.com/en/article/nft-collector-sells-peoples-fursonas-for-dollar100k-in-right-click-mindset-war/.Porres, Diego, and Alex Gomez-Villa. 2024. “At the Edge of a Generative Cultural Precipice.” arXiv.

https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2406.08739.Riley, Jessica. 2025. “The Annual Furry Convention, Anthrocon 2025, Returns to Pittsburgh This Weekend.” CBS News, July 3.

https://www.cbsnews.com/pittsburgh/news/anthrocon-returns-to-pittsburgh-2025/.Soatak. 2021. “A Furry’s Guide to Cryptocurrency.” Dhole Moments, April 19.

https://soatok.blog/2021/04/19/a-furrys-guide-to-cryptocurrency/.Statista. 2022. “Digitalization of the Arts and Culture Sector Worldwide.”

https://www.statista.com/study/90209/digitalization-of-the-arts-and-culture-sector-worldwide/.Stella. 2025. Virtual interview with the author, October 6. Transcript available upon request.

Thelot, Ruby Justice. 2023. “On Furries and the Limits of Trustlessness.” FWB, January 12.

https://v1.fwb.help/editorial/on-furries-and-the-limits-of-trustlessness-crypto.Tokranova, Darja, and Merja Lina Bauters. 2025. “Reflecting on Digital Art Value: NFTs’ Potential for the Art-Market Parity.” Digital Humanities in the Nordic and Baltic Countries Publications 7 (2).

https://doi.org/10.5617/dhnbpub.12293.Weiss, Ashli, and Melodi Özer. 2022. “NFTs: What You Need to Know to Protect Copyrights.” The Brand Protection Professional 7 (2).

https://bpp.msu.edu/magazine/nfts-what-you-need-to-know-to-protect-copyrights-june2022/.