“Our history has proved that each time we broaden the base of abundance, giving more people the chance to produce and consume, we create new industry, higher production, increased earnings and better income for all.”

On January 20, 2025, Donald Trump was sworn in as the 47th President of the United States of America. On his first day in office, he signed 26 Executive Orders (EOs). And as of May 12, 2025, he had signed 151 EOs, many of which directly reverse previous presidents’ orders and many of which have an adverse effect on artists and arts infrastructure If you are anything like me, you may have questions – many questions – about what all of this means. The following article offers a breadth of understanding of EOs, Appropriations, and the relationship between Johnson’s Great Society work and the attack on its fundamental components by the current political machine.

What is an Executive Order?

The term has been flying around the media on a daily basis since the Trump Administration took office, but a full scope of how EOs function is missing. So, what are EOs, where do they come from, how can they be used by a president, and what are the limits to the power they have?

Executive Orders are “official directives issued by the president to federal agencies within the executive branch… While Executive Orders carry the force of a law, they are not actual laws” (Civic Review, 2025, 0:58). They are one of several executive actions that a president can take. Other executive actions include proclamations, appointments, pardons, memorandums, or anything that “...Congress doesn’t need to be involved in” (Civics 101 5:27). EOs must be filed in the Federal Register. It is important to note that the power the president has to issue executive orders is not clearly stated in the Constitution. There are, however, three points that are referred to when understanding if an Executive Order is legally implemented:

Article II Section III - “He shall take Care that the Laws be faithfully executed, and shall Commission all the Officers of the United States.” (U.S. Const., art. II,§ 3) In a sense, this explains that it is the president's job to enforce laws passed by Congress. An example of this can be seen from Lyndon B. Johnson later in the article when he uses EO 11246 to enforce nondiscrimination after the passing of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. It is noteworthy that, in this point, the power is framed by enforcement, not creation of policy.

Article II Section I - “The executive Power shall be vested in a President of the United States of America.” (U.S. Const., art. II, § 1) You may notice that this wording is quite vague. But, the interpretation used is that the President will have power over the executive branch. Hence, orders are issued as directives specifically to agencies within the executive branch.

Article II Section II - “The President shall be Commander in Chief of the Army and Navy of the United States, and of the Militia of the several States, when called into the actual Service of the United States…” (U.S. Const., art. II, § 2) This grants the president the ability to give executive orders in regards to national security. We can see this implied power in action with EO 14165 signed by President Donald Trump on his first day of his second term.

Throughout history, EOs have been used in different ways. One of the very first was when George Washington issued neutrality in the French Independence War. Another famous order was the Emancipation Proclamation. While we can trace EOs back to George Washington, the first numbered EO was not signed until 1862, under Abraham Lincoln. EOs can be used to uphold and enforce existing laws or on an emergency basis. Refer to the example given with EO 11246 and the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

While EOs are a great power of the president, they are limited by law and are subject to review by other branches of the government. The limits to executive orders are as follows:

An EO cannot violate existing laws.

An EO can be limited by time because it is within the power of the president to reverse Executive Orders signed by previous presidents.

They are limited to the Executive branch and federal agencies housed within the Executive branch. (Ex: Education, FBI, DEA, Health, Agriculture, etc.)

The president still has to answer to the checks and balances of the legislative and judicial branches

This implied power of the president can help steer policy, but it is still subject to the checks and balances of the United States government. One way Congress can enact checks and balances is through the “power of the purse” or appropriations.

What are appropriations?

According to the U.S. House of Representatives Committee on Appropriations, the definition of an appropriation is as follows:

A law of Congress that provides an agency with budget authority. An appropriation allows the agency to incur obligations and to make payments from the U.S. Treasury for specified purposes. Appropriations are definite (a specific sum of money) or indefinite (an amount for "such sums as may be necessary"

There are 12 appropriation subcommittees:

Appropriation Subcommittees in Legislative Branch

Graphic by Author

The National Endowment for the Arts and the National Endowment for the Humanities are housed in the “Interior, Environment, and Related” appropriations committee. And in a similar vein, the Institute for Museum and Library Services is housed in the Labor, Health and Human Services appropriations committee.

These appropriations are run through the House Committee on Appropriations and the Senate Committee on Appropriations. Once the committees have established a plan for funding, it isvoted on by Congress and the Senate. When funds have been delegated through appropriations, the funds must be spent in the approved time frame (typically a fiscal year).

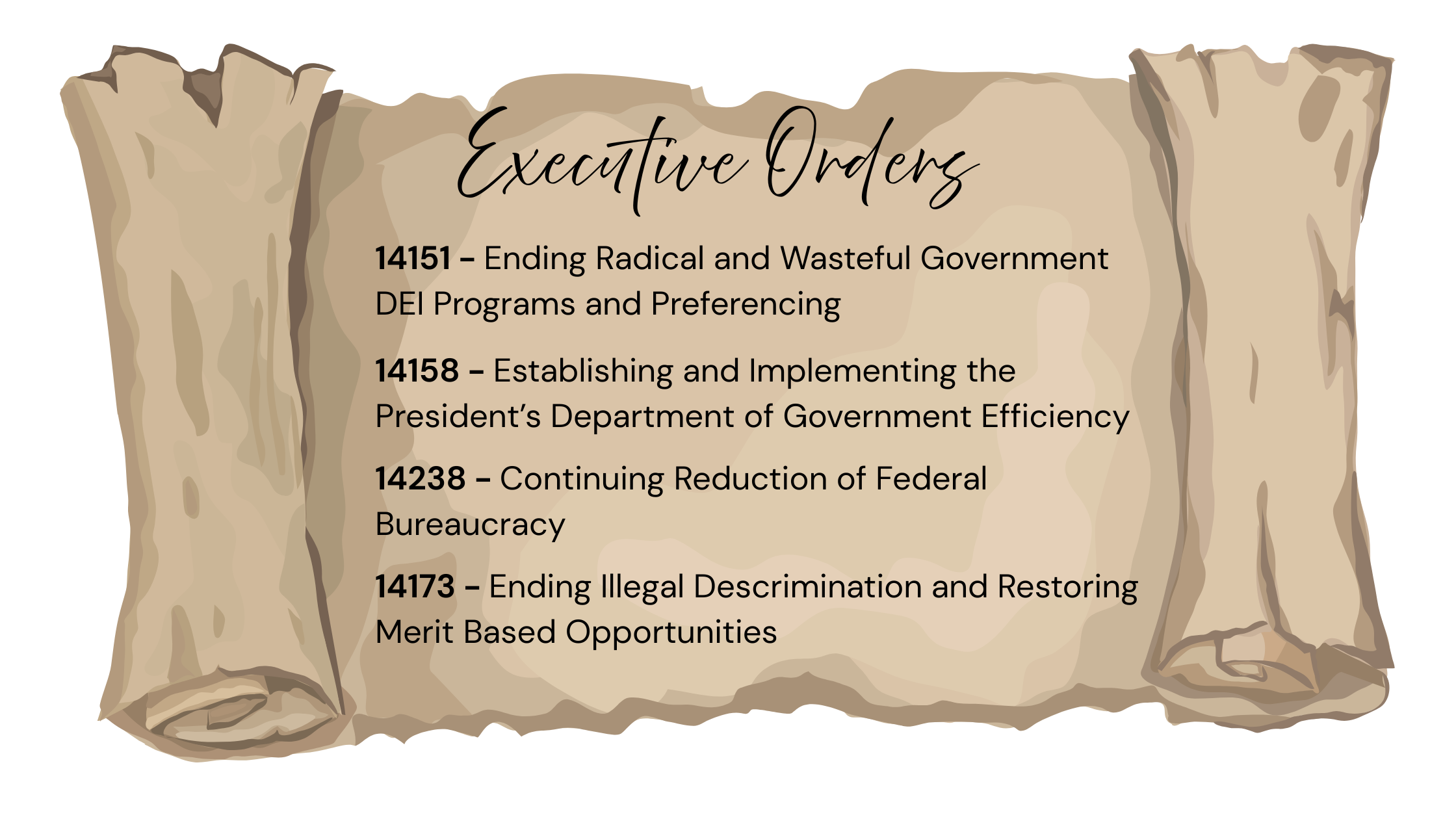

EOs 14151, 14158, 14238, and 14173 are, as of publishing this article, the primary EOs pertaining to the arts. It is important to note that none of them directly state that they are de-funding any of the said appropriations. However, they put in place the mechanisms for the actions that have led to the dismantling of IMLS and the reduced funding available for the NEH and NEA.

Defining Executive Orders 14151, 14158, 14238, 14173.

Graphic by Author

On March 14, 2025, EO 14238 called for the elimination of (to the maximum extent of the law) the Institute on Museum and Library Services (IMLS). As a result of the new Department of Government Efficiency, IMLS was deemed unnecessary. IMLS provides grants to libraries and museums in the United States. IMLS granted $266 million in 2024 alone. This money helps provide programming, but it also helps these organizations stay staffed and maintain necessary operations. As of March 21, 2025, the entirety of IMLS staff have been placed on administrative leave, and the status of grants from IMLS are uncertain. Many fear without staff to administer grants, the grants will be discontinued. Though as mentioned earlier, funding for IMLS is a part of the appropriations process. The president can recommend a budget for IMLS, but it is ultimately the decision of Congress as to how much funding the agency will receive.

In a similar vein, the National Endowment for the Humanities (NEH) placed 80 percent of its staff on administrative leave. This comes after the news that there will be no funding coming from NEH in 2025 even if previously awarded. A notice was sent to local humanities councils and stated the following: “Your grant no longer effectuates the agency's needs and priorities and conditions of the Grant Agreement and is subject to termination…Your grant's immediate termination is necessary to safeguard the interests of the federal government, including its fiscal priorities.” The NEH is another government agency whose funding is decided on by an appropriations committee. And most recently the NEA has suspended the many of their grants which had already been awarded.

As these EOs come out and as the Department of Government Efficiency continues to deem some government agencies unnecessary, we are likely to see litigations follow. In fact, several nonprofits have filed lawsuits in response to EO 14151. Due to these lawsuits, the funding freeze implemented out of this EO has been suspended as the Supreme Court reviews the case.

Furthermore, some of these EOs directly reverse the work done by Lyndon B. Johnson’s in The Great Society program. For instance, EO 14173 directly reverses EO 11246 that established Equal Opportunity Employment. Previously mentioned, EO 11246 was to better enforce the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

Other EOs indirectly affect the work done in The Great Society project. EOs 14151, 14238, and 14158 have effects on programs implemented during President Johnson’s administration. Many of these effects have come in the form of reduction of funding, but have also had an effect on employment of many working in national arts institutions.

Wait, what is the Great Society project and how is it related to the arts?

It is important to understand how the arts organization mentioned were initially developed and how they were set up to function. Many of the government arts agencies and social programs we are accustomed to came from Lyndon B. Johnson’s Administration and the Great Society Project.

Following the assassination of President John F. Kennedy, Lyndon B. Johnson was sworn in as the 36th president of the United States of America. Through his administration, he set goals and policies to fulfill his vision of America as The Great Society. President Johnson’s speech on The Great Society demanded an end to racial injustice and poverty and a pursuit of happiness for all American people. During his first term in office, President Johnson followed through on the work of President Kennedy by passing the Civil Rights Act on July 2, 1964. The passing of the Civil Rights Act helped President Johnson secure his second term in office which allowed him to continue his work on The Great Society project (Andrew, 1998). The programs resulting from his work are still used today and are important to note in the current political climate.

During a special message to Congress on March 16,1964, President Johnson demanded “... a national war on poverty. Our objective: total victory” (Johnson 1964). This “War On Poverty” (WOP) had five key proponents laid out by Johnson in the Economic Opportunity Act.

First was to build skills in young American workers that did not or could not finish their education due to poverty. This is where he introduces the ideas of Job Corps, Work-training Program, and Federal Work-study Program. All of these programs were built to give on the job training in different capacities. The Job Corps allowed those unable to do manual labor to train in an office setting. The Work-training Program benefited both sides of the coin. On one hand, it provided training to unemployed or uneducated workers, but it also provided staff for institutions that were in desperate need of help such as hospitals, libraries, playgrounds, and settlement houses. Other presidents have built on that work, for example, President Barack Obama expanded the Jobs Act during his term. Finally, the Work-Study Program would help students that could not afford college by allowing them to work their way through school (though now this idea may be outdated due to inflation and the rise of tuition).

The second portion of President Johnson’s plan was the Community Action Program (CAP). As the name entails, CAP called on communities to formulate plans to help to attack poverty long term. President Johnson’s belief was that local citizens understood their problems more than the people in Washington ever could. Though these plans did have to be approved by the federal Office of Economic Opportunity because of the financial backing of the federal government.

Next, Johnson asked to call on volunteers to help with the war on poverty. He stated, “They have skills and dedication. They are badly needed.” (Johnson 1964).

The fourth opportunity outlined by President Johnson was to create job opportunities for the worst off with incentives to employers that would hire them. This portion also outlined support for farming families. It would help them to purchase land and organize cooperatives.

The final piece of the plan to fight poverty was to ensure that it had structure and was not just a shot in the dark that failed due to lack of direction. This created the Office of Economic Opportunity which lay in the Executive Office of the President (an important distinction when it comes to Executive Orders that will be explained later).

The Economic Opportunity Act was signed into law on August 20, 1964 just a little over a month after signing the Civil Rights Act on July 2, 1964. And at the end of 1964, Lyndon B. Johnson was up for re-election against Barry Goldwater. Many attribute the Civil Rights Act to Johnson’s victory over Goldwater. Nevertheless, President Johnson’s re-election provided him with four more years to fight the war on poverty.

On January 4, 1965 President Johnson delivered a State of the Union address with an appeal to pursue The Great Society. This included the expansion of the WOP and enforcement of the Civil Rights Act, but it also expanded to include an increase in the quality of life for the American people with a focus on economic growth, opportunity for all, and enriching the lives of all. Among the actions proposed by Lyndon B. Johnson was reducing costs for farmers, regional recovery programs, transportation projects, expansion of Social Security benefits, a new immigration law, expanding school programs, the National Foundation for the Arts, and several others you can find in his State of the Union Address.

Some of the important laws coming out of The Great Society project were the Elementary and Secondary Education Act of 1965, The Second Supplemental Appropriation Act, Medicare, and the Arts and Humanities Bill. Of course the one of the most important focuses for Arts Managers is the Arts and Humanities Bill which established the National Endowment for the Arts and National Endowment for the Humanities.

Since its start, the National Endowment for the Arts has provided grants to nonprofit arts organizations throughout America. It helps small and large organizations alike and a look at the NEA funding for the past five years is found below.

During his elected term in office, Johnson also issued Executive Orders. To ensure nondiscrimination in the workplace, President Johnson signed Executive Order 11246 entitled “Equal Employment Opportunity” in 1965 (amended in 1967 to include rights to women). As mentioned previously, this EO was an enforcement of existing law. The Civil Rights Act of 1964 Title VII prohibits employment discrimination over race, color, religion, sex, and national origin. President Johnson’s EO 11246 strengthened the already existing law.

Pew Research Center demonstrated the effect The Great Society and WOP had on the American people. They found that (adjusting for inflation) poverty dropped from 26% in 1967 to 16% in 2012 (poverty is currently 12.5%). They also found that older generations are not as poor as they previously were. Those suffering most from poverty are those ages 18-64. Though there is argument about the success of President Johnson’s Great Society and War on Poverty, there has been progress in lowering poverty in The United States.

For a detailed timeline of The Great Society and President Lyndon B. Johnson’s time in office, visit the American Presidency Project by the University of California Santa Barbara.

What can be done now?

New headlines of executive actions seem to appear everyday. So, as the terrain is ever changing, what can we do as art professionals? First, we must remember that there was a time before the arts were supported by the government. Artists have a unique skill of making the most of what we have. Next, call your representatives. This article has explained that the legislative branch has the power to check the president. They delegate funding to agencies. So, call your representatives to express the importance of the arts in your area. Not sure what to say? Here is an example script. Finally, continue making and supporting art. Humanity is expressed through art, and we need that now more than ever.

-

Andrew, J. A. (1998). Lyndon Johnson and the Great Society. I.R. Dee.

“Annual Message to the Congress on the State of the Union.” Annual Message to the Congress on the State of the Union | The American Presidency Project, January 4, 1965. https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/documents/annual-message-the-congress-the-state-the-union-26.

Congress. Accessed April 6, 2025. https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/R/R48255.

Bailey, Martha J, and Nicolas J Duquette. “How Johnson Fought the War on Poverty: The Economics and Politics of Funding at the Office of Economic Opportunity.” The journal of economic history, June 2014. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC4266933/#abstract1.

“Bending toward Justice: 60 Years of Civil Rights Laws Protecting Workers in America.” US EEOC. Accessed April 6, 2025. https://www.eeoc.gov/bending-toward-justice-60-years-civil-rights-laws-protecting-workers-america.

Blair, Elizabeth. “Cultural Groups across U.S. Told That Federal Humanities Grants Are Terminated.” NPR, April 3, 2025. https://www.npr.org/2025/04/03/nx-s1-5350994/neh-grants-cut-humanities-doge-trump.

Blair, Elizabeth. “National Endowment for the Humanities Staff Put on Immediate Leave.” NPR, April 4, 2025. https://www.npr.org/2025/04/04/nx-s1-5352422/neh-staff-administrative-leave.

“Continuing the Reduction of the Federal Bureaucracy.” The White House, March 15, 2025. https://www.whitehouse.gov/presidential-actions/2025/03/continuing-the-reduction-of-the-federal-bureaucracy/.

Daniller, Andrew. “5 Facts about Americans’ Views of Government.” Pew Research Center, February 25, 2025. https://www.pewresearch.org/short-reads/2025/02/25/5-facts-about-americans-views-of-government/.

DeSilver, Drew. “Who’s Poor in America? 50 Years into the ‘War on Poverty,’ a Data Portrait.” Pew Research Center, January 13, 2014. https://www.pewresearch.org/short-reads/2014/01/13/whos-poor-in-america-50-years-into-the-war-on-poverty-a-data-portrait/.

“Executive Action and Their Impact on Charitable Nonprofits.” YouTube. Accessed April 6, 2025. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yoobIvi2_cc.

“Federal Appropriations Process: Ryan Shay, March RDLA Webinar.” YouTube. Accessed April 8, 2025. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tXH3FGP6Z3w.

Federalregister. Accessed April 1, 2025. https://archives.federalregister.gov/issue_slice/1984/6/1/22770-22793.pdf.

Federalregister. Accessed April 6, 2025. https://public-inspection.federalregister.gov/2025-01953.pdf.

Federal Register :: Eliminating the Federal Executive Institute. Accessed April 1, 2025. https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2025/02/14/2025-02734/eliminating-the-federal-executive-institute.

Federal Register :: Ending illegal discrimination and restoring merit-based opportunity. Accessed April 1, 2025. https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2025/01/31/2025-02097/ending-illegal-discrimination-and-restoring-merit-based-opportunity.

Federal Register :: Reforming the federal hiring process and restoring merit to government service. Accessed April 1, 2025. https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2025/01/30/2025-02094/reforming-the-federal-hiring-process-and-restoring-merit-to-government-service.

Glossary of terms. Accessed April 1, 2025. https://www.house.gov/the-house-explained/open-government/statement-of-disbursements/glossary-of-terms.

“Implementing the President’s ‘Department of Government Efficiency’ Cost Efficiency Initiative.” The White House, February 27, 2025. https://www.whitehouse.gov/presidential-actions/2025/02/implementing-the-presidents-department-of-government-efficiency-cost-efficiency-initiative/.

Johnson, L. B., Makematic, production company, & Johnson, L. B. (Lyndon B. (2020). Untold. Lyndon B. Johnson : the Great Society speech. Makematic.

“Landmark Laws of the Lyndon B. Johnson Administration.” LBJ Library. Accessed April 1, 2025. https://www.lbjlibrary.org/life-and-legacy/landmark-laws.

Legislation.pdf. Accessed April 1, 2025. https://www.arts.gov/sites/default/files/Legislation.pdf.

“Lyndon B. Johnson Event Timeline.” Lyndon B. Johnson Event Timeline | The American Presidency Project, November 22, 1963. https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/documents/lyndon-b-johnson-event-timeline.

Limbong, Andrew. “Entire Staff at Federal Agency That Funds Libraries and Museums Put on Leave.” NPR, March 31, 2025. https://www.npr.org/2025/03/31/nx-s1-5334415/doge-institute-of-museum-and-library-services?utm_source=facebook.com&utm_medium=social&utm_term=nprnews&utm_campaign=npr&fbclid=IwZXh0bgNhZW0CMTEAAR3CRMFKfiqgOkDcvVKOCNwhnNjIEvyA2dFZvD4rzz4KF2-g7oQHKXbbJIo_aem_i9bB9jCIcU1pDf-6P_cJXA.

Nayyar, Rhea. “Trump Disbands President’s Committee on Arts and Humanities .” Hyperallergic, February 19, 2025. http://hyperallergic.com/987623/trump-disbands-presidents-committee-on-arts-and-humanities/.

Pontone, Maya. “National Gallery of Art Ends Diversity Programs.” Hyperallergic, January 27, 2025. https://hyperallergic.com/985640/national-gallery-of-art-ends-diversity-programs/.

“Remarks at the Signing of the Arts and Humanities Bill.” Remarks at the Signing of the Arts and Humanities Bill | The American Presidency Project, September 29, 1965. https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/documents/remarks-the-signing-the-arts-and-humanities-bill.

Sarmiento, Isabella Gomez. “During Tour, Trump Declares the Kennedy Center Is in ‘Tremendous Disrepair.’” NPR, March 17, 2025. https://www.npr.org/2025/03/17/nx-s1-5330840/trump-kennedy-center-honorees-board.

Snider, Brett. “What Are Executive Orders? What Are Their Limits? - Findlaw.” Edited by Madison Hess. What Are Executive Orders? What Are Their Limits?, January 8, 2025. https://www.findlaw.com/legalblogs/law-and-life/what-are-executive-orders-what-are-their-limits/.

“Special Message to the Congress Proposing a Nationwide War on the Sources of Poverty.” Special Message to the Congress Proposing a Nationwide War on the Sources of Poverty | The American Presidency Project, March 16, 1964. https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/documents/special-message-the-congress-proposing-nationwide-war-the-sources-poverty.

“State Profiles.” National Endowment for the Arts. Accessed April 1, 2025. https://www.arts.gov/impact/state-profiles.

“Trump’s Impact on the Arts: A Running List of Updates.” Greater Pittsburgh Arts Council, April 2, 2025. https://www.pittsburghartscouncil.org/blog/trumps-impact-arts-running-list-updates.

Ulaby, Neda. “The Smithsonian Will Close Its Diversity Office and Freeze Federal Hiring.” NPR, January 29, 2025. https://www.npr.org/2025/01/29/nx-s1-5279225/smithsonian-diversity-office-president-trump-executive-order.

U.S. Constitution. "Article II: The Executive Branch." https://constitution.congress.gov/constitution/article-2/

“What Are the Limits to Executive Orders? A Constitutional Explanation.” YouTube, January 28, 2025. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UoVtZknCqVI.