In a previous publication, The Connection Of Digital Placemaking And Inequity, the concept of digital placemaking was introduced and compared to creative placemaking. While aiming to instill a sense of meaning and belonging in a place, digital placemaking actually has the potential to cause harm to communities by perpetuating digital inequities. Nevertheless, digital placemaking interventions are increasingly implemented in cities for economic benefits. The interplay of technology and placemaking can accelerate gentrification by continuing to exclude digitally disadvantaged groups. This article will address these issues further and provide recommendations for the next steps by examining the intersection of digital placemaking, digital equity, and the arts and culture sector. The arts can be an aide in bridging the digital divide as artists and organizations continue their work in equity, inclusion, and accessibility. Additionally, as arts organizations increase their digital programming, digital equity becomes a significant consideration.

Introduction

In an increasingly digitized world, the relevance of physical space is increasingly diminished. Digital placemaking interventions, however, aim to engage people in public spaces by creating a hybrid digital/physical space, thus attaching a sense of meaning to a physical place. An example of such technologies includes Pokemon Go, which uses gamification and AR technology to encourage users to explore and interact with physical space. A study by Jennifer Barton and other researchers at Miami University examined how gamification could increase exposure to and participation in the arts by surveying Pokemon Go users. While gamification and other digital placemaking strategies no doubt increase the use of local spaces, the digital divide serves as a barrier for a large portion of the general US population.

The digital divide impacts roughly 157 million Americans in rural and urban areas. Current digital placemaking efforts automatically exclude the portion of the US population with little or no digital access and literacy by creating a prerequisite for participation. As a result, those having the privilege of digital access and literacy construct the meaning of digital participation, which will be discussed in more detail in the next section. This fact runs parallel to creative placemaking efforts in which local communities are seldom invited to participate in decision-making. Economic benefits typically lay at the forefront of placemaking goals. Thus, true community impact is often not considered. Although more equitable approaches to creative placemaking, such as asset-based community development, are being utilized, the inequity issues in creative placemaking have nevertheless passed on to digital placemaking.

Technology is often regarded as making life easier. It has become more integral to daily life in an increasingly digitized world. The implementation of digital technologies in placemaking efforts has the potential to create a more digitally equitable society. Various placemaking approaches and interventions can be updated to incorporate an equitable lens. Moreover, because of the artistic and creative aspect of many digital placemaking projects, the arts and culture sector has the opportunity to be more vocal about digital equity efforts, both inside and outside the scope of its offerings.

An Overview of Digital participation and Inequity

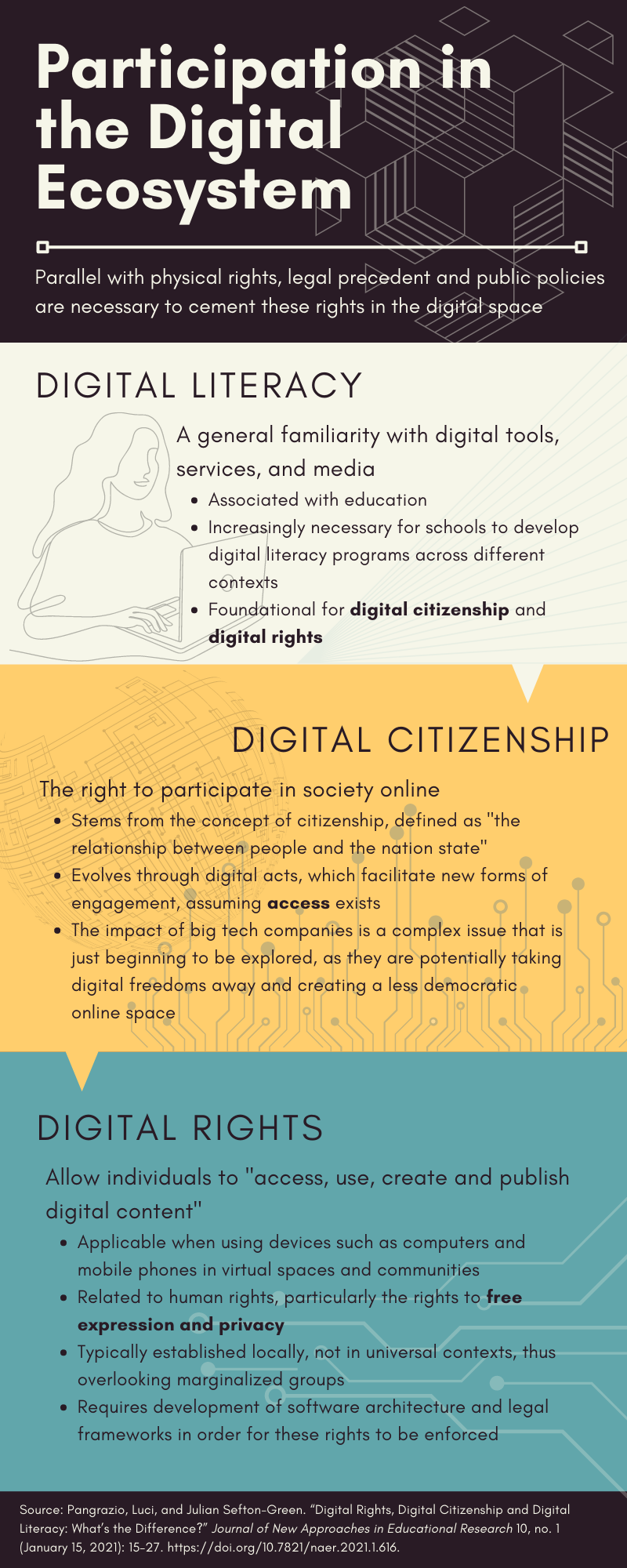

Technology has penetrated every aspect of social, economic, political, and personal life. The interplay of citizenship, rights, and literacy ultimately determines an individual’s ability to live in digitally mediated societies, just as in the physical world.

Digital citizenship evolves through the digital acts a person undertakes and, over time, facilitates new forms of digital participation. Current debates over whether access to the Internet is a human right in and of itself are ongoing. Advocates for digital equity argue that it is an issue related to human rights as it pertains to freedom of expression and privacy. Because these freedoms are inherent in an individual’s digital rights, it can be argued that access to the Internet and other digital services is a human right. This assertion is especially the case considering more essential services such as banking, retail, health care, education, and public amenities are moving toward virtual spaces.

Digital rights allow an individual to access, use, create and publish digital content on devices such as computers and mobile phones, as well as in virtual spaces and communities. They pertain to participation in a virtual space through the use of computers and smartphones, which ties directly into digital literacy and having the knowledge to access this space. Digital literacy is the foundation for digital citizenship and rights and is broadly defined as a general familiarity with digital tools, services, and media. Without digital literacy, individuals cannot participate or claim their digital rights if they are not ‘literate’ in the first place. However, states have devolved their power to establish digital rights to the private sectors, which own and manage digital sites, services, and infrastructure and participate in discriminatory practices such as digital redlining. This is a practice in which Internet Service Providers (ISPs) purposefully and knowingly invest in fiber optic infrastructure in wealthy neighborhoods in densely populated cities, skipping over low-income neighborhoods in those same cities. A lack of digital citizenship, rights, and literacy in a significant portion of the US population, along with a lack of regulation on these large corporations, has led to this commonplace practice.

A 2022 report by the National League of Cities found three primary causes of digital inequity:

Affordability, meaning the cost of devices and broadband service is not within reach.

Access, where Broadband service at adequate speed and quality is not available.

Skills, pertaining to digital literacy and having the necessary skills to use technology successfully.

Any combination of these barriers impacts many groups of people in different ways. For example, the “homework gap” differentiates the portion of K-12 students who have internet access and those who do not. Students without internet access have a more difficult time completing assignments and accessing online learning environments. Households earning an annual income of less than $20,000 have a broadband adoption rate of 62%. This figure is 81.8% for households earning more than $75,000 annually. This imbalance places low-income families at more of an educational disadvantage, as 50% lack access to devices at home that would allow them to access distance learning. Later in life, those entering the workforce are less likely to find employment if they lack internet access. The number of opportunities that present themselves to impacted individuals then becomes limited.

One fallacy is that access alone automatically grants equity and inclusion. However, affordability and literacy are necessary for technology to integrate effectively into our daily lives. There are large systemic equity challenges that are the crux of digital inequity. Several paths toward digital equity have been proposed and theorized. One article posits that action in the form of education, research, and regulation needs to be taken against these challenges. Another publication by Robbie McBeath names access, adoption, and use as pathways toward digital equity and names structural and human interactions as its root cause. McBeath additionally states that a “community-driven inclusive approach is essential for digital equity work - not dissimilar to community-driven placemaking being essential for transformation.” With its focus on digital technologies, a digital placemaking framework toward digital equity is highly feasible. Reframing digital placemaking to a community-driven, needs-based approach can create a more digitally equitable environment for all community members. However, this is not the primary aim of many current digital placemaking efforts, and community input is often not sought.

Figure 1. Source: Author

Current Placemaking Shortcomings

The digital inequities that impede a broader reach of digital placemaking efforts are the basis of some common criticisms expressed by Marcus Foth:

Digital placemaking creates a risk of ignoring the history of a place that came before placemaking efforts.

Placemaking has historically favored those that fund the projects rather than a place’s current or future residents.

The economic benefits of placemaking efforts create explicit or inadvertent support for the gentrification of cities.

The scale and impact of placemaking projects tend to limit themselves to small clusters of a city rather than a city as a whole, hindering any chances at broader systemic change.

In connection with digital inequity, the last two points are especially evident. The success of current creative placemaking efforts is typically measured in economic value. Authors of the article Determining and Representing Value in Creative Placemaking claim that this focus is “often at the expense of these other important social and environmental values that contribute to the production and perceptions of a place by its communities.” Metrics that are not explicitly tangible marginalize disadvantaged and underrepresented groups in communities. Most digital placemaking efforts are currently used to create positive economic outcomes in the cultural tourism sector, driving the wedge into the digital divide even further.

Because many of these efforts are initiated from the top-down, little room is left for community members to voice their needs and concerns regarding any community development projects in their own neighborhoods. The danger in this approach lies in the choice of location for digital placemaking to take place. Because of the economic incentive from increased tourism, digital technologies are often placed in locations in cities that arguably stand to benefit the least socially from digital placemaking. These areas are often ones with a high level of digital literacy. As literacy is one of the significant factors of the digital divide, it is an essential element to consider concerning digital placemaking. A study on the effects of digital placemaking on senior citizens found that there can be several positive impacts of digital technologies used in placemaking initiatives - collectivization, digital urban commons, and an increased sense of community. However, this only occurs when sufficient attention is paid to the digital literacy of participants.

In a 2015 survey on creative placemaking, the National Endowment for the Arts (NEA) found that many carrying out creative placemaking projects lack the knowledge to execute them properly. The future of placemaking efforts will require a greater collection of knowledge and research, distribution, and understanding of that knowledge. Truly equitable outcomes of placemaking must ensure that federal investments support the entire community. This can partially be attained through the arts sector developing a better understanding of community development.

Digital inequity in the arts

Technology simultaneously presents an opportunity and a challenge for arts organizations. One article from Grantmakers in the Arts explains, “Technological advancements mean that once-disparate issues are now inextricably linked. This, too, creates new opportunities for us to make an impact, provided we remain engaged and mindful of where our interests lie in the emerging digital ecology.” The inequities that grip the digital placemaking field run parallel with those impacting the arts sector. The following graphic compares several characteristics of each field and how they intersect with the issue of inequity.

Figure 2 source: author

To clarify the notion that the arts contribute to gentrification, research on the role of different types of art in gentrification processes has been done to provide some support for arts-based revitalization initiatives. A 2014 study on the extent of the arts' role in neighborhood gentrification found that arts-based community development efforts are “more likely associated with neighborhood revitalization that benefits existing residents.” Commercial arts, which include film, music, and design, were found to have a significant association with gentrification and no relationship to neighborhood revitalization. However, fine arts, defined as for-profit and nonprofit visual and performing arts, had a weak but positive association with revitalization and a negative correlation with gentrification. It is important to note that literature on arts-based gentrification is highly contextual, making it difficult to claim absolutely that an arts presence hinders or catalyzes gentrification. However, this study alone presents a knowledge base for those working on placemaking projects involving the arts, physical or digital, and allows them to anticipate the possible outcomes of their decisions better.

The association between the arts sector and digital inequity may only appear at a glance. Nevertheless, as more institutions create digital and hybrid programming in hopes of reaching more audiences, they are only basing their actions on the assumption that access will lead to inclusion and need to consider the actual state of digital equity in their communities. Ensuring that more members of their communities have access to high-quality, affordable broadband service will strengthen the ability of artists and arts organizations across the United States to compete in a global marketplace. Current literature on digital placemaking most commonly discusses its potential usage for attracting arts patrons and cultural visitors to an urban area, thereby naming the arts as a partner in these efforts. Equity and inclusion in these projects are areas in which the arts can be a leader.

Interventions Toward Digital Equity

As Tom Eitler of the Urban Land Institute stated, “creative placemaking isn’t just an aesthetic choice – it’s a vital tool for urban development and renewal.” The approaches used in placemaking processes ultimately determine its community impact, whether it is positive or negative. Joel Fredericks, Luke Hespanhol, and Martin Tomitsch discuss three approaches to placemaking:

Opportunity-based

Asset-based

Need-based

Opportunity-based placemaking relies on economic opportunities that present themselves in an area. Incorporating this capitalistic approach in placemaking usually discriminates between affluent and lower socioeconomic demographics.

Asset-based placemaking is gaining momentum in more community development initiatives. Here, the focus is on long-term, equitable outcomes through the collaboration of various stakeholders in a community, including the residents.

Need-based placemaking depends on the scale, context, and purpose of the needs of a community. This approach could be central to digital placemaking efforts to increase digital equity where low access and literacy rates are.

Additionally, the authors advocate for a “middle-out” approach to placemaking in which community members and other stakeholders collaborate in the decision-making process. Contrary to a “top-down” or “bottom-up” approach, the goal of a middle-out approach is to integrate the needs and wants of decision-makers somewhere in the middle with those of everyday people—fostering a more collaborative approach. A more equitable approach would be for those at the top with the resources and tools required to carry out community development projects to take guidance from community residents whose impact will be felt the greatest.

Current literature on digital placemaking often focuses on its potential usage in cities to attract arts patrons and cultural visitors, targeting a particular demographic that already has the privilege of digital citizenship. There are, however, various digital placemaking interventions discussed by Fredericks, Hespanhol, and Tomitsch that have the potential to be used as tools for input or engagement in communities where digital services or access are lacking.

City hacking involves citizen-led, small-scale interventions that temporarily change the nature, feeling and use of the place. This change could include a minor alteration to a physical space in the form of a protest to call attention to an issue and advocate for just change.

Wayfinding directs people on specific cycling and walking paths, encouraging the curated exploration of a place. Signage could direct residents to an outdoor walking path or public area that provides free high-speed internet.

Guerrilla art, or “street art,” is a form of DIY city hacking through art installation in public spaces. It can be used as a specialized form of city hacking to draw public attention to the issue of digital inequity.

Small-scale media interfaces offer data-gathering capabilities and instant visualization of results. These technologies are often pop-up digital voting booths intended to gather community input on a specific topic. Participation is achieved through eye-catching or visually appealing digital screens or interfaces that intrigue citizens.

These tools have already been implemented in various projects around the United States on digital placemaking projects focusing on digital equity. One example comes from Miami, where over 30% of the population lacks internet access. The Underline is a space under Miami’s Metrorail that has been transformed over the years from a piece of empty, unused land to a community area that will, in the coming years, feature walking and biking trails, local art, and free high-speed internet. This project used community-centered technology to bridge the local digital divide explicitly. This placemaking project was a collaboration between the nonprofit Friend of the Underline, a philanthropic organization, local government, and private entities.

Reconsidering the social impact of digital placemaking could help bridge the digital divide in many marginalized communities across the country. This would also make project outcomes easier to measure for social value, as increased digital education and access opportunities can be clearly defined outcomes. For those pursuing digital placemaking efforts, it is recommended to become aware of how specific actions can accentuate current digital equity gaps.

How the Arts Can Begin to Bridge the Digital Divide?

“Leading the way has never been easy, but it is not an unusual task for artists and creatives. Arguably, it has always been part of the job description.”

The arts have historically been at the forefront of many social and cultural issues, often offering commentary and raising awareness in novel and imaginative ways. The challenge of digital equity is no different. As further efforts are made towards digital equity across sectors, opportunities for artists and arts organizations to become involved are growing. However, as we progress into the digital age, artists and creatives can become key drivers of the changes ahead (Restrepo, Buitrago, Lynch, 69). One major challenge in addressing digital inequity is tackling its three primary obstacles - literacy, affordability, and access. The arts can play a crucial role in addressing just one of these factors in education, affordability, access, and advocacy.

Figure 3 source: author

Education

The COVID-19 pandemic has compounded educational inequities in the US. As more schools invested in technologies for remote learning, students of color were disproportionately impacted. A paper by Stephen J. Aguilar found that schools’ investments in new technology have the potential to create barriers for low-income students. Recognizing that access to technology does not grant inclusion and may exacerbate existing barriers is imperative.

A National Endowment for the Arts report entitled Tech as Art: Supporting Artists Who Use Technology as a Creative Medium found that artists working at the intersection of arts and technology are better equipped to deal with societal and sector-related issues. Digital equity and literacy are often already at the forefront of tech-centered artists’ work. This positions them as valuable partners for policymakers, educators, and practitioners in arts and non-art sectors. With digital literacy and a lack of basic computer skills being significant barriers to digital equity, digital education is a critical area in which artists can become involved. There are more opportunities than ever for these initiatives, which depend on successful partnerships with other educators and nonprofits. However, many of these artists claim that their potential to be a partner in these issues is often overlooked. The report recommends that field practitioners and arts researchers promote ways that artists address issues around digital equity and inclusion.

By highlighting current contributions, the arts and culture sector will be equipped to advocate for higher arts funding, STEAM education, and digital inclusion and training initiatives. A rise in STEAM education in K-12 settings presents ample opportunities for tech-centered artists. Agnes Chavez, a new media artist, educator, producer, and founder of the STEMarts Lab, posits that new media artists have much to contribute to closing the digital divide in society. Tech-centered arts projects involving transdisciplinary educational initiatives offer students exposure to digital technologies, a crucial first step toward digital inclusion. However, the adoption of STEAM initiatives and the cultivation of partnerships with tech-centered artists have the potential to go beyond simple exposure to digital technologies. In his essay, A Call-to-Action in STEAM Education, S. Craig Watkins states that digital artists are an “untapped resource in our quest to strengthen STEAM literacy in this country.” Not only can they offer education on the use of technology, but also an ethical component to tech and digital literacy training. Watkins notes that we can become “more intentional in building technologies that are more oriented towards social and racial justice,” but only through including artists and creatives in the conversations.

Aside from K-12 education initiatives, digital skills training for adults is equally vital in combatting digital literacy gaps. This is an area where organizations can open their space for education programs or even where individuals can offer their expertise. At the Cleveland Public Library, staff member Matthew Sucre offers computer and digital skills classes to the local community. Over 55 students regularly attend his classes. By incorporating a human-centered, growth mindset-based approach to teaching digital skills, he has changed how he and other staff look at patrons and their approach to digital learning.

Another component of education is research. This is an area that could be improved when it comes to digital inequity and the societal impacts of technology. For those with the ability, the National Endowment for the Humanities (NEH) offers grants to researchers exploring the impacts of technology on society from a humanistic and cultural perspective. Through the Dangers & Opportunities of Technology grant program, the NEH will award grants to individuals and teams of researchers analyzing technology’s impact on society through the humanities and humanistic social sciences.

Affordability & Access

Because many nonprofits are already positioned to offer educational services, they can offer digital access to their communities. Many nonprofit arts organizations now have hybrid and virtual offerings designed to expand their reach beyond their typical audience. By opening their doors for arts events, especially those including a digital component, nonprofit organizations can provide free wifi and digital devices in their buildings for all who visit. They can also open their space for digital equity activities, such as panel discussions, community meetings, classes, workshops, or digital media artist presentations.

Much of the arts’ involvement in digital affordability comes from advocacy, which is discussed in the next section. However, offering free or affordable admission to events that include digital features and are targeted toward digitally underserved communities provides an additional service to a portion of the population impacted by the digital divide.

Advocacy

Artists and arts organizations can greatly help digital placemaking initiatives by engaging in conversations around and championing digital equity in the projects in which they involve themselves. Because most nonprofit arts organizations operate as 501c3s, there are limits on the extent to which they are allowed to get involved in politics. However, a 501c3 status does allow for considerable communication advocacy and lobbying. Most arts nonprofit organizations are already established as community-centered entities that typically work closely with community members and may be familiar with the community's issues. For that reason, they are better positioned to serve as a voice for what their community needs that goes beyond their mission. A component of advocacy includes educating the public about the lack of access to basic needs and services that a proportion of the local population experiences.

Advocacy tasks can be limited to small-scale, local efforts or can adjoin a larger-scale national effort, depending on the capacity of the organization. Partnering with other organizations, especially those with a greater knowledge base on digital inequity, can help a nonprofit assemble its key talking points. Opera America drafted a policy brief on the importance of the arts in public transit, infrastructure, and digital equity in collaboration with several other organizations in a coalition known as the Cultural Advocacy Group. The brief stated that arts and culture organizations can contribute to digital inclusion activities and that the NEA should be a partner in implementing the Digital Equity Act. Of course, similar efforts can take place on state or local levels. Advocacy efforts toward digital equity on a smaller scale are necessary and foundational toward broader national policies. Even before states began receiving funds from the Digital Equity Act, several have started digital equity projects involving workforce and adult education, assessment and research, and county-level digital equity initiatives.

As more states enforce various digital equity projects, strategic partnerships that venture outside the nonprofit arts sector become key. Arts organizations can establish cross-disciplinary alliances with lawmakers, government officials, funders, other nonprofits, and private entities to share resources and knowledge. In this way, they can redefine what arts advocacy means in the 21st century.

Conclusion

For the arts sector to continue on a path of equity and inclusion for all members of the communities they serve, the digital divide needs to be addressed. The world is becoming increasingly digitized, impacting arts organizations and their audiences. The recommendations provided in this article serve primarily as starting points for ways in which the arts sector can create a more digitally inclusive and equitable environment. As digital placemaking efforts rise in popularity, more emphasis should be placed on what they can do to help drive social change rather than solely economic change. This process can be repurposed to work with educators, arts organizations, artists, and digital equity advocates to create a more equitable society and ensure digital citizenship for all.

-

Aguilar, Stephen J. “Guidelines and Tools for Promoting Digital Equity.” Information and Learning Sciences 121, no. 5/6 (January 1, 2020): 285–99. https://doi.org/10.1108/ILS-04-2020-0084.

“Background.” The Underline. Accessed November 29, 2022. https://www.theunderline.org/background/.

Basaraba, Nicole. “The Emergence of Creative and Digital Place-Making: A Scoping Review across Disciplines.” New Media & Society, September 30, 2021, 14614448211044942. https://doi.org/10.1177/14614448211044942.

Bergson-Shilcock, Amanda. “States are leading the way on digital equity.” National Skills Coalition. March 22, 2022. https://nationalskillscoalition.org/blog/digital-equity/states-are-leading-the-way-on-digital-equity/.

Brennan, Sheila. “New Dangers and Opportunities of Technology Grant Program.” National Endowment for the Humanities. October 3, 2022. https://www.neh.gov/blog/new-dangers-and-opportunities-technology-grant-program.

“Building Connections to Change Lives, Digital Inclusion Fellowship Cohort 7.” The Nonprofit Technology Enterprise Network. November 8, 2022. https://www.nten.org/publications/2021-digital-inclusion-fellowship-spotlights.

Chavez, Agnes. “How Artists Can Bridge the Digital Divide and Reimagine Humanity.” June 2021. Accessed November 18, 2022. National Endowment for the Arts. https://www.arts.gov/impact/media-arts/arts-technology-scan/essays/how-artists-can-bridge-digital-divide-and-reimagine-humanity.

Chen, Kuangfan, Mirko Guaralda, Jeremy Kerr, and Selen Turkay. “Digital Intervention in the City: A Conceptual Framework for Digital Placemaking.” URBAN DESIGN International, September 20, 2022. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41289-022-00203-y.

Cook, Jean, Adam Huttler, and Helen De Michiel. “The Future of Digital Infrastructure for the Creative Economy.” GIA Reader Vol 21, No 2 (Summer 2010). https://www.giarts.org/article/future-digital-infrastructure-creative-economy.

“Creative Placemaking Recommendations from and Impact of Six Advisory Services Panels.” Urban Land Institute. 2022. Accessed November 19, 2022. https://knowledge.uli.org/-/media/files/research-reports/2022/uli-aspr_creative-placemaking_9-26.pdf?rev=54ae1000dcfa4f29b35d66faeb74f9cb&hash=51F2442A3A93D33D70CE9ADD8BD6810A.

Cultural Advocacy Group. “Arts in Infrastructure: Supporting Arts in Public Transit, Infrastructure, and Digital Equity Projects.” Opera America. Accessed December 5, 2022. https://www.operaamerica.org/media/jysf20pe/arts-in-infrastructure-supporting-arts-in-public-transit-infrastructure-and-digital-equity-projects.pdf.

Daly, Meg. “How Miami’s New Linear Park Is Using ‘Community-Centered Technology’ to Bridge the Digital Divide.” Brookings (blog), August 30, 2022. https://www.brookings.edu/blog/the-avenue/2022/08/30/how-miamis-new-linear-park-is-using-community-centered-technology-to-bridge-the-digital-divide/.

“Digital Equity Handbook: How City Leaders Can Bridge the Digital Divide.” National League of Cities. Accessed October 23, 2022. https://www.nlc.org/resource/digital-equity-playbook-how-city-leaders-can-bridge-the-digital-divide.

Foth, Marcus. “Some Thoughts on Digital Placemaking.” In Media Architecture Compendium: Digital Placemaking, edited by L. Hespanhol, H. M. Hausler, M. Tomitsch, and G. Tscherteu, 203–5. Germany: avedition GmbH, 2017. https://www.avedition.de/en/media-architecture-compendium-digital-placemaking/978-3-89986-251-5.

Fredericks, Joel, Luke Hespanhol, and Martin Tomitsch. “Not Just Pretty Lights: Using Digital Technologies to Inform City Making.” In Proceedings of the 3rd Conference on Media Architecture Biennale, 1–9. MAB. New York, NY, USA: Association for Computing Machinery, 2016. https://doi.org/10.1145/2946803.2946810.

Fuld, Joe. “Advocacy and politics: how your nonprofit can get more involved.” The Nonprofit Technology Enterprise Network. October 15, 2020. https://www.nten.org/blog/advocacy-and-politics-how-your-nonprofit-can-get-more-involved.

Grodach, Carl, Nicole Foster, and James Murdoch III. “Gentrification and the Artistic Dividend: The Role of the Arts in Neighborhood Change.” Journal of the American Planning Association 80, no. 1 (January 2, 2014): 21–35. https://doi.org/10.1080/01944363.2014.928584.

McBeath, Robbie. “Pathways to Digital Equity: How Communities Can Reach Their Broadband Goals—and How Philanthropy Can Help.” Benton Institute for Broadband Society. November 7, 2022. https://www.benton.org/publications/Pathways.

Pangrazio, Luci, and Julian Sefton-Green. “Digital Rights, Digital Citizenship and Digital Literacy: What’s the Difference?” Journal of New Approaches in Educational Research 10, no. 1 (January 15, 2021): 15–27. https://doi.org/10.7821/naer.2021.1.616.

Peyman Najafi, Masi Mohammadi, Pascale M. Le Blanc & Pieter van Wesemael (2022): Insights into placemaking, senior people, and digital technology: a systematic quantitative review, Journal of Urbanism: International Research on Placemaking and Urban Sustainability, DOI: 10.1080/17549175.2022.2076721.

“Organizations ask incoming Biden FCC to Ban Digital Redlining.” Electronic Frontier Foundation. November 24, 2022. https://www.eff.org/document/organizations-ask-incoming-biden-fcc-ban-digital-redlining.

Quaintance, Zack. “Digital Equity Takes Center Stage in U.S. Cities Post COVID.” Government Technology. March 2022. https://www.govtech.com/civic/digital-equity-takes-center-stage-in-u-s-cities-post-covid.

Restrepo, Felipe Buitrago, and Robert L. Lynch. Arts & the Workforce: Excerpted from Arts & America: Arts, Culture, and the Future of America’s Communities. Edited by Clayton Lord. (Americans for the Arts, 2015), 65-76.

Scorse, Yvette. “What Is Digital Inequity?” National Digital Inclusion Alliance. October 4-8, 2021. https://www.digitalinclusion.org/blog/2021/10/06/what-is-digital-inequity/.

Schupbach, Jason. “The Next 50 Years of Creative Placemaking: Some Thoughts.” The National Endowment for the Arts. January 14, 2015. https://www.arts.gov/stories/blog/2015/next-50-years-creative-placemaking-some-thoughts.

“Tech as Art: Supporting Artists Who Use Technology as a Creative Medium.” National Endowment for the Arts. June 2021. Accessed November 18, 2022. https://www.arts.gov/sites/default/files/Tech-as-Art-081821.pdf.

“The FCC must end digital redlining.” The Nonprofit Technology Enterprise Network. May 16, 2022. https://www.nten.org/blog/a-consultants-take-on-tech-equity.

Vaughan, J., K. Maund, T. Gajendran, J. Lloyd, C. Smith, and M. Cohen. “Determining and Representing Value in Creative Placemaking” 14, no. 4 (2021): 430–45. https://doi.org/10.1108/JPMD-07-2019-0069.

Watkins, S. Craig. “A Call-to-Action in STEAM Education,” National Endowment for the Art. June 2021. Accessed November 18, 2022. https://www.arts.gov/impact/media-arts/arts-technology-scan/essays/call-action-steam-education.