Art heists in the modern world

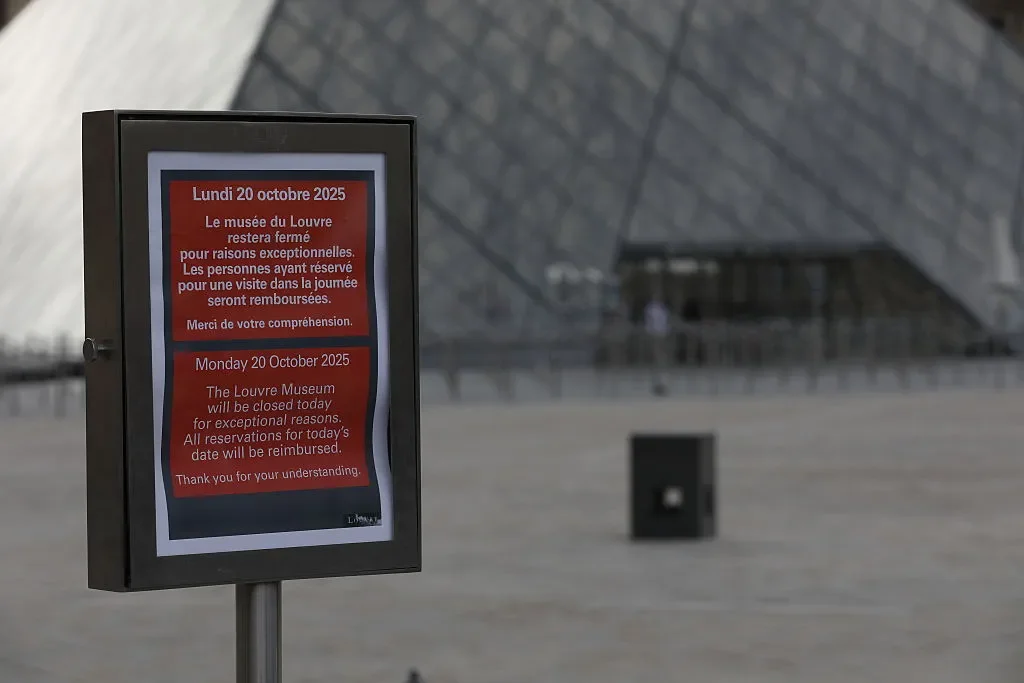

In Mid-October, the Musée du Louvre, a global cultural institution in Paris, France and home to the Mona Lisa and Venus de Milo, experienced a high-profile security breach via a daylight robbery. The targets were priceless pieces from the French Crown Jewels housed within the Galerie d’Apollon (Apollo Gallery). Following the incident, the museum promptly closed its doors to facilitate a comprehensive investigation and reopened later.

Figure 1: The Galerie d’Apollon at the Louvre Museum. Source: photo by Ludovic Marin/AFP via Getty Images)

The event has since broadened into a critical conversation for the arts sector, encompassing initial arrests, analyses of outdated security infrastructure, and a comparison to an apparent increase in similar thefts across Europe. Furthermore, commentary from security experts has provoked the hypothesis of an inside job, citing digital evidence that allegedly compromised internal protocol. Ultimately, this crisis serves as a critical case study in the complexities of running a major cultural institution.

Figure 2: A general view shows the Louvre Museum a day after thieves stole eight priceless royal pieces of jewelry from the museum, as tourists continue to visit the area to take photos despite the closure, in Paris, France, on October 20, 2025. Source: Anadolu via Getty Images

A Breakdown of Security: How the Jewels Were Taken

While much of the heist’s breakdown has been covered across multiple platforms, I’ll reiterate the key details to provide context for the points discussed later. A question to keep in mind for the public and arts professionals is how the robbers gained such detailed knowledge of the vulnerabilities within the world’s most-visited museum.

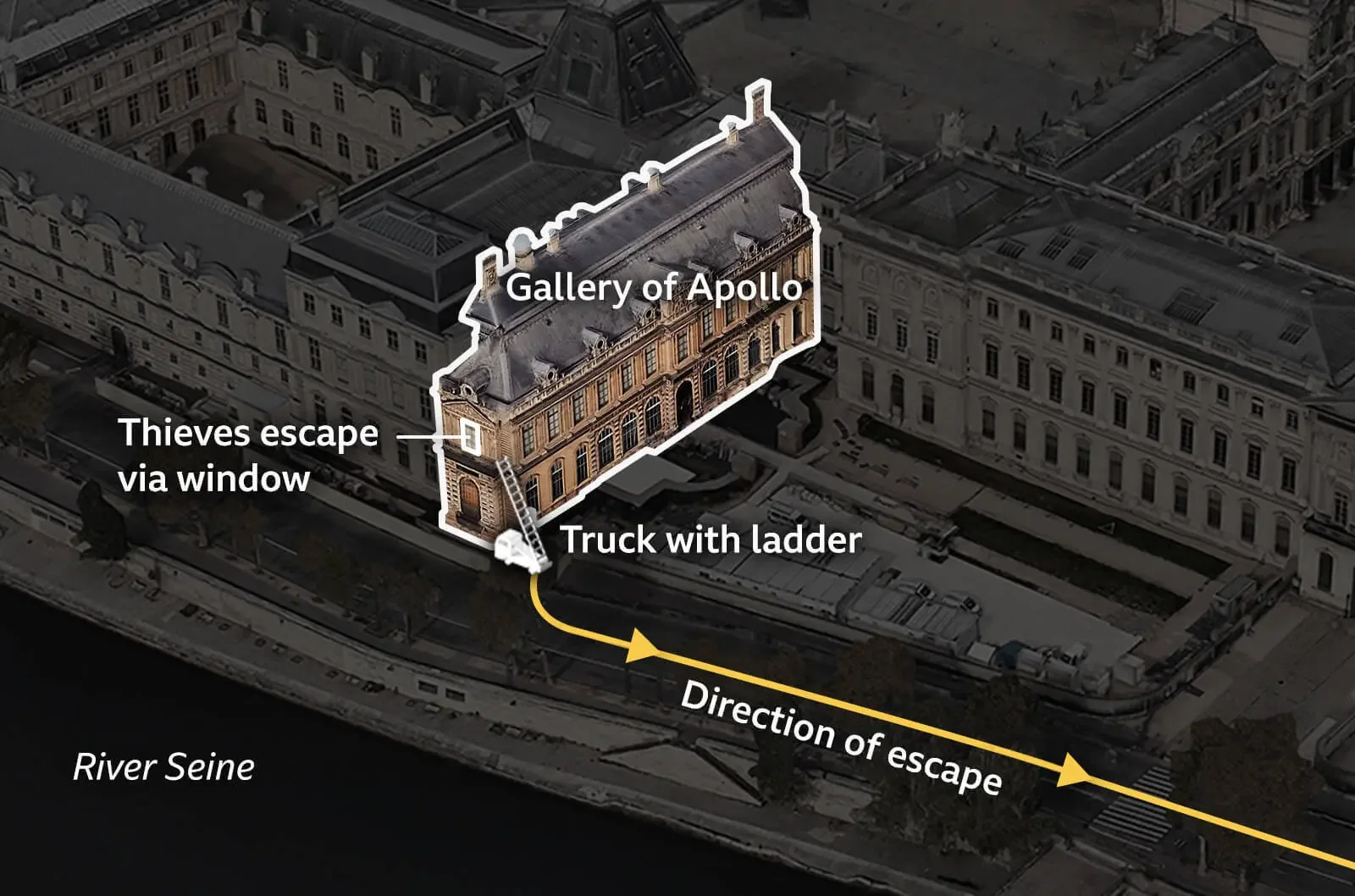

Figure 3: Source, BBC

The robbery was executed around 9:30 a.m., shortly after the museum opened and as visitors began to fill the exhibition spaces. The four-person team arrived in a stolen truck equipped with a mechanical ladder, which they positioned against a second-story window of the Denon Wing. Two assailants, masked and dressed in reflective high-visibility vests, scaled the ladder and used angle grinders to cut through the wood and glass windows.

Figure 4: Phone capture of one of the assailants. Source, BFMTV

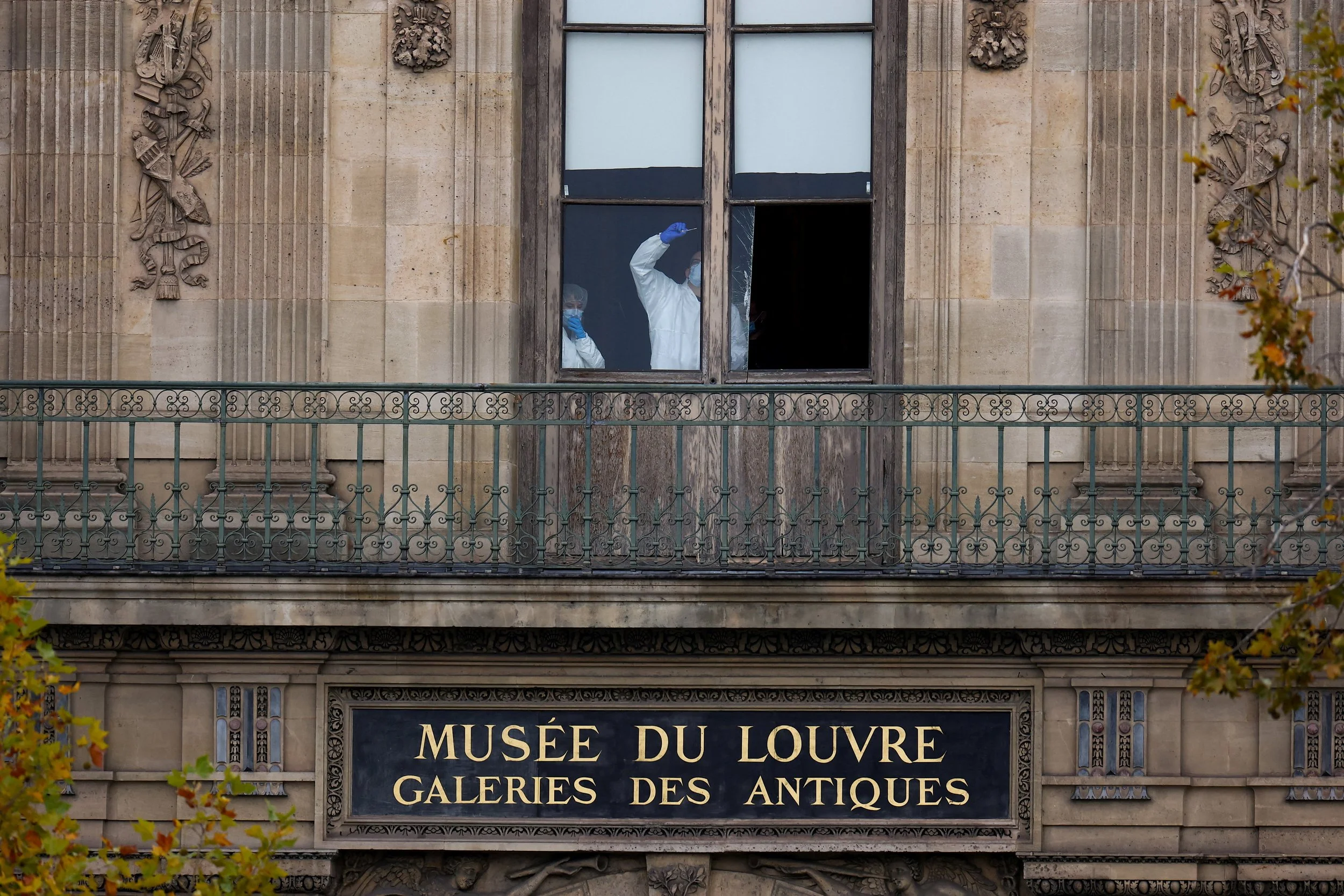

French authorities later confirmed that the opulent gallery windows were not reinforced. In a span of five minutes, the thieves entered the Galerie d’Apollon, brandished the angle grinders to threaten and provoke unarmed guards into fleeing, and used power tools to shatter the glass display cases. French broadcaster, BFMTV ,later released footage showing one of the thieves operating within the historic hall, which has held the French Crown Jewels for over a century.

By 9:35 a.m., news of a disturbance was spreading among museum staff, with witnesses reporting an atmosphere change as guards began marching guests away from the gallery. Before their escape, the thieves attempted to set fire to the mechanical ladder they had used to gain access. They then reportedly fled on high-powered Yamaha TMAX scooters, capable of speeds over 100 mph, maneuvering quickly through the narrow Parisian streets.

While the thieves attempted to take nine items, one centuries-old object was dropped and ultimately broken by investigators outside the museum during the escape.

Figure 5: Graphic illustration Source, BBC

The Element of Compromise

The precision and planning of the theft strongly suggested an intimate knowledge of the museum's operational weaknesses. Investigators uncovered evidence that pointed toward an insider threat, with digital forensic analysis reportedly showing communication between at least one member of the Louvre's security staff and the suspected perpetrators prior to the heist.

Sources close to the investigation claimed that sensitive, internal information regarding the museum's security protocols was intentionally passed on, providing the assailants with the critical intelligence needed to identify the precise window and access point. This development underscores a shift in risk assessment for cultural institutions, moving beyond simple perimeter defense to address the complex threat of internal collaboration.

Figure 6: Police and forensic teams inspect a crane and a window believed to have been used in what the French Interior Ministry said was a robbery at the Louvre museum during which jewelry was stolen, as pedestrians pass nearby, in Paris, France, October 19, 2025. Source: REUTERS/Gonzalo Fuentes

The successful transfer of remaining precious items from the Galerie d’Apollon to a more secure location, carried out under secret police escort days after the heist, confirmed the immediate need for a complete reevaluation of the museum's security protocols. The subsequent sections will detail the historical and cultural significance of the priceless items stolen, analyze the subsequent public outcry and leadership responses, and examine the broader context of recent high-profile cultural thefts to explore potential correlations and preventative strategies for arts management.

The Crown Jewels: Objects of Inestimable Heritage Value

The stolen objects, valued at an estimated €88 million (approximately $102 million USD) excluding their historical significance, were collectively described as "items of inestimable heritage value" to France. Most of the targeted sacred jewels were from the 19th Century, belonging to royal figures such as Napoleon III, Queen Marie-Amélie, Queen Hortense, and Empress Eugénie.

Figure 7: French Crown Jewels, Sources: Louvre Museum and BBC

The eight items successfully stolen included:

[1-3] Parts of the sapphire jewelry set of Queen Marie-Amélie and Queen Hortense: A Diadem, necklace, and a pair of earrings.

[4-5] Parts of the emerald Marie-Louise set: An emerald necklace and earrings, originally given as a wedding gift by Napoleon Bonaparte to his second wife, Marie-Louise.

[6-7] Diadem and Large bodice knot (brooch) of Empress Eugénie: A pearl and diamond tiara and a large diamond brooch.

[8] A brooch known as the 'reliquary brooch.'

The ninth item, the Eugénie Crown, was damaged during the escape and recovered by investigators outside the museum.

Figure 8: Eugénie Crown, Louvre Museum, Source: Getty Images

Organizational Backlash and Public Outcry

Beyond the obvious act of criminality, the heist has sparked intense controversy and public anger concerning the museum's management and security protocols. The Louvre is owned by the French government, and its highest executive position, the President-Director, is appointed directly by the French President.

President Emmanuel Macron's last appointment was Laurence des Cars in September 2021, making her the first woman to lead the institution. The President-Director also presides over the Louvre Endowment Fund, a non-profit organization established in 2009 to provide long-term financial support for the museum's public interest missions through donations and investments.

Figure 9: Emmanuel Macron at the Louvre, Paris, 28 January 2025. Photograph: Jacovides Dominique ABACA/REX/Shutterstock

Fueling the public outrage was the leak of a recent audit, conducted by France’s Court of Auditors (equivalent to the U.S. Government Accountability Office) at the request of des Cars shortly after her appointment. The audit revealed damning evidence of "repeated postponements of the scheduled modernization of security systems," stating that cameras were often installed "only when rooms have been refurbished," according to the French newspaper Le Figaro.

The report highlighted significant technological deficiencies: large parts of the museum lacked camera coverage, and existing units had not been replaced since 2019. In the Denon Wing, which houses the Galerie d’Apollon and the Mona Lisa, the audit confirmed that one-third of the rooms have no CCTV cameras.

The report also criticized the museum for failing to prioritize necessary security enhancements despite its annual operating budget of €323 million ($376 million), noting that “the amounts committed are small compared to the estimated needs.” This apparent discrepancy in the allocation of funds has further fueled public discontent.

Yet, in the wake of the robbery, museum officials have argued that despite being outdated, the current alarm systems did their job by alerting security. Nevertheless, this incident has brought President Macron's cultural leadership and the confidence of the Louvre’s director under intense scrutiny. The consensus is that cultural institutions must prioritize modernization, including the integration of next-generation technology such as motion, acoustic, and temperature sensors.

Potential Role of Artificial Intelligence

The critical debate arising from the Louvre heist is not merely about the quantity of cameras, but the quality of monitoring. Security experts suggest that simply adding hundreds more traditional cameras might not have prevented the theft, as conventional surveillance systems rely on human operators to watch dozens of feeds simultaneously. As such, these systems tend to be reactive: operators often notice an incident only after it has occurred, leaving the footage to serve solely as evidence rather than a tool for prevention.

This dynamic could potentially suggest a need for institutions to explore solutions such as AI-equipped cameras. These systems could add a new layer of security by learning a camera's surroundings and alerting operators when an event is out of the ordinary. As an example of this capability, a self-learning video surveillance system—such as the one promoted by Macnica Americas in collaboration with icetana AI—is designed to monitor hundreds of cameras simultaneously, surfacing only the most relevant events for an operator to review.

This technology could shift the focus away from static rules or simple motion detection. Instead, the AI learns the normal behavior patterns within each camera view, including people walking to maintenance work and identifies anomalies that might signal a potential threat. In a hypothetical application to the Louvre robbery, could AI-enabled cameras notice the presence of individuals posing as workers in yellow vests and masks in non-construction areas or could the system flag a truck-mounted lift driving up to the building as an anomaly?

The Downside: AI, Security, and the Surveillance Economy

While the proactive potential of AI in security is possible, its broader implementation must be viewed through the lens of the Surveillance Economy. This term, coined by scholar Shoshana Zuboff, refers to a new economic order where private corporations unilaterally claim and extract personal human experience as free raw material—called "behavioral surplus"—to create prediction products.

The concern is that the same powerful AI tools used to spot an intruder in a museum are also the engines driving this data-extraction economy. The core problem is the resulting asymmetry of power and knowledge, where individuals and institutions are largely ignorant of how their data is being used to predict and ultimately modify behavior for corporate profit. In a secure environment, an AI flags an anomaly to protect an asset; in the commercial world, AI processes data from your location, searches, and even facial recognition (if implemented) to predict what you'll do next and subtly manipulate your choices—from personalized pricing to political targeting.

The widespread adoption of AI-enabled surveillance, particularly in "smart city" infrastructure, means that the fight against crime runs the risk of becoming part of a larger, commercialized system that erodes individual autonomy and privacy. In this environment, the line between security and commercially-driven social control becomes dangerously blurred, raising profound ethical and democratic questions that policymakers must address.

Recent Updates and Arrests:

Just a week after the daring daytime heist, the massive manhunt yielded swift results, culminating in the apprehension of four suspects, all with the crucial help of DNA forensic analysis. Detectives were able to identify and ultimately apprehend four individuals through DNA traces collected from more than 150 forensic samples at the crime scene and on objects the thieves left behind, including power tools, gloves, and a motorcycle helmet. In a dramatic display of investigative urgency, one of the men, who were all in their 30s and known to police, was even taken into custody while attempting to board a flight bound for Algeria at Paris’s Charles de Gaulle Airport.

Figure 12: Suspects charged in Louvre Case, Source: ABC News, Paris Public Prosecutor, Adobe

While the arrests signal significant progress, the task of recovering the priceless jewels remains ongoing. The Paris Prosecutor, Laure Beccuau, voiced hope that the intense, global media coverage of the highly organized robbery might actually aid recovery efforts, and would deter the perpetrators from moving the highly recognizable, “unsellable” objects far.

However, this progress was immediately clouded by a leak of information to the press, which the prosecutor publicly regretted, citing the potential to hinder the efforts of the more than a hundred investigators mobilized in the complex case. The swift identification and capture of suspects, despite the organizational upsets in such a high-profile case, momentarily shifts the narrative from institutional failure to the resilience of cultural property protection.

A Deeper Conversation: Colonial Legacy and Global Theft

Across social media, the cinematic nature of the robbery has prompted commentary, often from a comedic standpoint, suggesting that the incident "was something out of a movie." However, the events have also opened up a necessary, "sticky" conversation about cultural responsibility, particularly concerning the dark history of European colonialism and the unethical procurement of such treasures.

The jewels themselves are more than iconic objects of immense value; they are products of a long history of colonial extraction. The sapphires, emeralds, diamonds, pearls, and other gemstones—such as the 32 emeralds and 1,138 diamonds in the Marie-Louise parure, or the 212 pearls and nearly 3,000 diamonds in the Diadem of Empress Eugénie—were mined across Asia, Africa, and South America. These regions were systematically exploited for their cultural and natural resources to enrich European courts. These artifacts carry a legacy of exploitation, colonization, slavery, and violence, a history inseparable from their display in the Louvre.

For many, this heist is a heartbreak for France, mirroring the generations of suffering endured by origin communities whose cultural and natural heritage was looted and exploited to create these very symbols of European power.

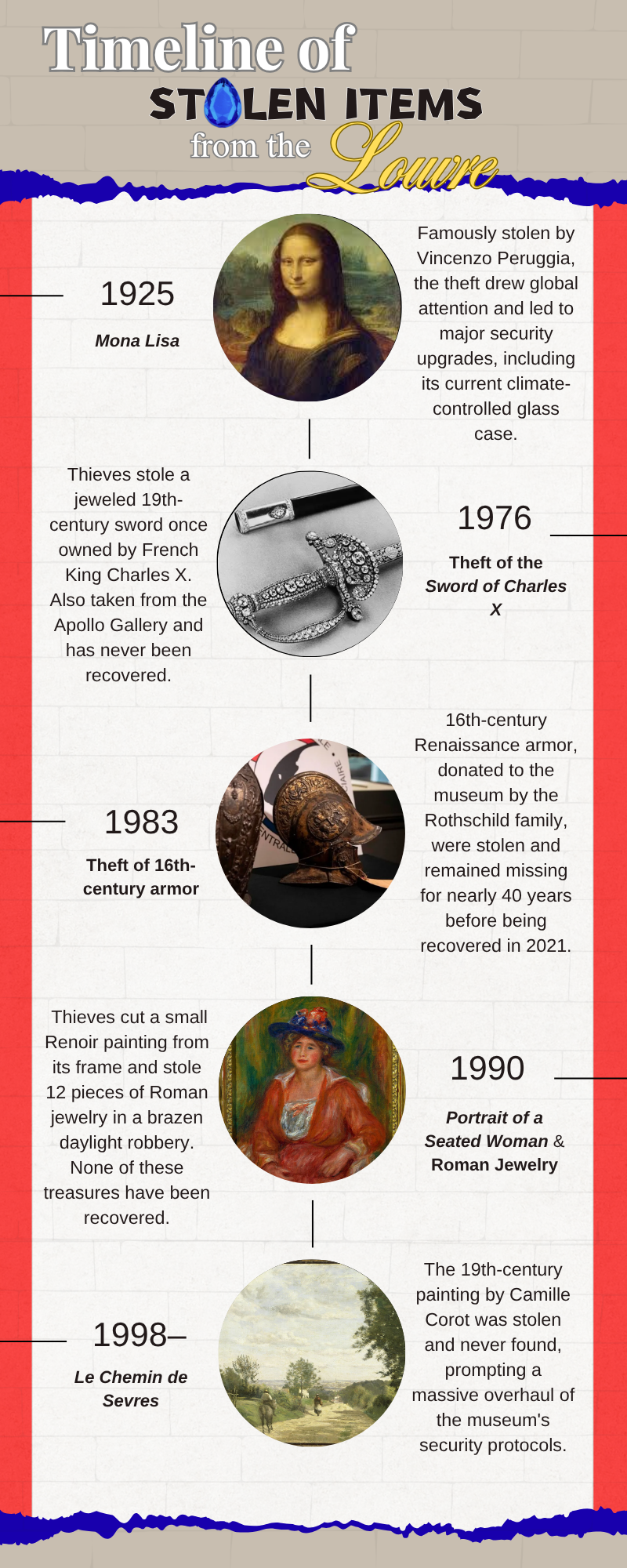

Timeline of Global Art Heists

Figure 13: Graphic of past thefts at the Louvre

The 2025 Louvre robbery now sits in a historical continuum of sporadic but highly impactful cultural thefts, providing context for the enduring challenges facing modern institutions. These incidents highlight the sophisticated nature of determined thieves and the lasting impact such losses have on cultural heritage.

Moreover, there’s been a troubling string of recent high-value thefts across Europe, suggesting a possible correlation and a shifting motivation among organized criminal groups. For example, in March 2020, as COVID-19 lockdowns began, a priceless early Vincent van Gogh painting, The Parsonage Garden, was stolen from the Singer Laren Museum in the Netherlands by a thief using only a sledgehammer to defeat multiple security layers.

More recently, French museums have faced a spate of attacks, including the theft of porcelain works valued at €9.5m (approx. $11 millon) from the Adrien Dubouche Museum in Limoges last month.

This troubling trend is not limited to high-value artwork. Other high-profile heists, such as the theft of gold samples from the Paris Natural History Museum in September, and golden Dacian treasures from the Drents Museum in the Netherlands in January, point toward a potential motivation shift.

Commentators have increasingly suggested that these patterns are potentially motivated by rising global market prices for precious metals. This perspective suggests that for modern thieves, the focus may be less on artistic provenance and more on the melt-down value and financial commodity of historical objects.

Beyond the Louvre: A Case of the Missing Picasso

In more unsettling news for the arts community, security failures are not limited to dramatic, organized break-ins. This reality was underscored by the recent misplacement of a Picasso artwork, Still Life with Guitar (1919), while it was in transport from Madrid to Granada.

Figure 15: “Still Life With Guitar,” a 1919 gouache and pencil work by Picasso, was recovered by Spanish police after disappearing in early October. Source: The New York Times

The print, which belonged to an unnamed private collector and was insured for €600,000 (around $700,000). The print was part of a 57-piece shipment and was reported missing after the transport van, during a journey that typically takes four to five hours, made an unscheduled overnight stop in the nearby town of Deifontes. The artwork was only confirmed absent two days after delivery to the foundation; staff noted that the packaging was "not all properly numbered," making immediate verification impossible. The package was supposed to be picked up by a courier inside a private building in northern Madrid, but was instead taken home by a woman who lived in the same building. The work was found a week later by police, yet no one has been charged with any crime.

This resolution provides a stark contrast to the professional, highly organized crime witnessed at the Louvre. It highlights that arts managers must contend with a broad spectrum of threats: not only the professional, high-stakes robberies but also the significant potential for mundane logistical and administrative mishaps that can jeopardize valuable cultural property.

The Road Ahead: Lessons in Security, Stewardship, and Social Justice

The audacious robbery at the Louvre transcends a typical news story; it represents a profound cultural and emotional shock for the French people. The loss of objects woven into the fabric of national identity is felt as a travesty against heritage, triggering a sense of disbelief and a realization that even the world's most powerful cultural institutions are vulnerable.

The public reaction, characterized by a mix of incredulous awe and social media commentary about an "old school heist," has quickly pivoted to more profound cultural questions. The fact that the targeted items were the French Crown Jewels immediately brought the spotlight to the complicated history of their provenance. These jewels, composed of resources extracted from former French colonies through systems fueled by slavery and violence, are a painful reminder of the colonial legacy underpinning the wealth of many European institutions.

These heists, whether low-tech or highly professional, highlight the enduring, almost mythical challenge of securing invaluable cultural artifacts. The complexity of the Louvre job, and its success in escaping with unsellable high-value objects, suggests the presence of a sophisticated network. This elevates the concern from simple burglary to the actions of a specialized, possibly global, enterprise targeting cultural institutions.

However, whether an explicitly outlined heist or simple human error, the lapsed protection of cultural items forces the art world to address a dual mandate: prioritizing modern security against theft while simultaneously pursuing historical accountability and transparency regarding the provenance of their collections.

-

Arranz, Adolfo, Han Huang, Jitesh Chowdhury, and Vijdan Mohammad Kawoosa. “How Thieves Broke into the Louvre Museum and What They Stole.” Reuters, October 20, 2025. https://www.reuters.com/graphics/FRANCE-CRIME/LOUVRE/byprezooove/.

Breeden, Aurelien. “See What Was Taken in the Louvre Heist.” The New York Times, October 19, 2025. Updated October 27, 2025. https://www.nytimes.com/2025/10/19/world/europe/louvre-heist-items.html.

Breeden, Aurelien. “Suspects Arrested over the Theft of Crown Jewels from Paris’ Louvre Museum.” The New York Times, October 26, 2025. https://www.nytimes.com/2025/10/26/world/europe/louvre-heist-arrests.html.

Brunton, Finn, and Helen Nissenbaum. “Vernacular Resistance to Data Collection and Analysis: A Political Theory of Obfuscation.” First Monday 16, no. 5 (May 2, 2011). https://doi.org/10.5210/fm.v16i5.3493.

Corbett, Sylvie. “Timeline of the Jewel Heist at the Louvre in Paris.” WRAL News / Associated Press, October 2025. https://www.wral.com/news/ap/a072c-a-timeline-of-the-jewel-heist-at-the-louvre-in-paris/.

Couldry, Nick, and Ulises A. Mejias. The Costs of Connection: How Data Is Colonizing Human Life and Appropriating It for Capitalism. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2019.

“Could AI Have Prevented the Louvre Jewelry Heist?” Macnica Blog. Accessed October 21, 2025. https://www.macnica.com/americas/mai/en/blog/could-ai-have-prevented-the-louvre-jewelry-heist/.

“Court of Auditors (Cour des Comptes).” République Française. Accessed October 21, 2025. https://www.ccomptes.fr/en.

Diallo, Rokhaya. “The Louvre Raid Was Political.” The Guardian, October 21, 2025. https://www.theguardian.com/world/commentisfree/2025/oct/21/france-louvre-raid-political-heist-president-emmanuel-macron-sebastien-lecornu.

Greenberger, Alex. “What We Know About the Louvre Heist So Far: How Did Thieves Steal $102 M. in Jewels?” ARTnews, October 22, 2025. https://www.artnews.com/list/art-news/news/louvre-heist-jewels-controversy-explained-1234758284/the-stolen-jewels-were-invaluable-or-are-worth-102-million/.

Ho, Karen K. “Stolen Vincent Van Gogh Painting Recovered from IKEA Bag.” ARTnews, September 12, 2023. https://www.artnews.com/art-news/news/stolen-vincent-van-gogh-painting-recovered-groninger-museum-ikea-bag-1234679475/.

Horowitz, Jason. “A Missing Picasso Is Found, and a Small Spanish Town Loses Its Air of Mystery.” The New York Times, October 24, 2025. Updated October 26, 2025. https://www.nytimes.com/2025/10/24/world/europe/spain-picasso-missing.html.

Hutchinson, Bill, and Lilia Geho. “Despite Charges Filed against Four Suspects in the Louvre Heist, Stolen Jewels Still Missing.” ABC News, November 3, 2025. https://abcnews.go.com/International/despite-charges-filed-4-suspects-louvre-heist-stolen/story?id=127128460.

Leath, Mason. “A History of Heists at the Louvre: From the Mona Lisa to Napoleon’s Jewels.” ABC News, October 20, 2025. https://abcnews.go.com/International/history-heists-louvre-mona-lisa-napoleons-jewels/story?id=126680032.

Macanidar, A. “Digital Surveillance Capitalism and Cities: Data, Democracy and Activism.” Humanities and Social Sciences Communications 11 (2024): 1533. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-03941-2.

Marshall, Alex. “See What Was Taken in the Louvre Heist.” The New York Times, October 19, 2025. Updated October 27, 2025. https://www.nytimes.com/2025/10/19/world/europe/louvre-heist-items.html.

Muzaffar, Maroosha. “Everything That Was Stolen in the Daring Louvre Heist.” The Independent, October 20, 2025. https://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/europe/louvre-heist-france-news-latest-what-was-stolen-b2848270.html.

Noce, Vincent. “French President Calls for a ‘New Renaissance’ of the Louvre.” The Art Newspaper, January 28, 2025. https://www.theartnewspaper.com/2025/01/28/emmanuel-macron-musee-louvre-renovations-expansion.

Paul, Andrew. “Popular Science: How the Louvre Heist Happened.” Popular Science, October 2025. https://www.popsci.com/technology/how-louvre-heist-happened/.

Petrequin, Samuel, and Nicolas Garriga. “Suspects Arrested over the Theft of Crown Jewels from Paris’ Louvre Museum.” AP News, October 26, 2025. https://apnews.com/article/france-louvre-heist-arrests-2e78cbea4bc44c39348eedf8baf138ed.

Smith, Emiline. “The Louvre Heist Was a Colonial Wake-Up Call.” Hyperallergic, October 2025. https://hyperallergic.com/1051113/the-louvre-heist-was-a-colonial-wake-up-call/.

“Surveillance Economy.” Sustainability Directory, August 22, 2025. https://lifestyle.sustainability-directory.com/term/surveillance-economy/.

“Louvre Museum Heist: Detectives Suspect Inside Job after Chainsaw Thieves Steal $100 Million Crown Jewels.” Times of India, October 25, 2025. https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/world/europe/louvre-museum-heist-detectives-suspect-inside-job-after-chainsaw-thieves-steal-100-million-crown-jewels/articleshow/124820951.cms.

“Louvre Museum Official Site.” Musée du Louvre. Accessed October 21, 2025. https://www.louvre.fr/en.

“State and Regional Organization.” Welcome to France. Accessed October 21, 2025. https://www.welcometofrance.com/en/fiche/state-and-regional-organization.

Visual Journalism Team. “How Louvre Gang Carried Out France's Most Shocking Theft.” BBC News, October 20, 2025. Additional reporting by Sean Seddon, Richard Irvine-Brown, and Paul Kirby. https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/resources/idt-fde5876a-c35c-48a2-b4cf-d255bd25611b.

Willsher, Kim. “Laurence des Cars Appointed First Female President of the Louvre.” The Guardian, May 26, 2021. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2021/may/26/louvre-appoints-laurence-des-cars-as-first-female-president.

“Yamaha Motor: MAX Lineup.” Yamaha Motor Global Business. Accessed October 21, 2025. https://global.yamaha-motor.com/business/mc/lineup/max/.

Zuboff, Shoshana. The Age of Surveillance Capitalism: The Fight for a Human Future at the New Frontier of Power. New York: PublicAffairs, 2019.