Interactive theatre is gaining increasing attention from both artists and audiences. While these models are not entirely new—such as the 1980’s plays The Mystery of Edwin Drood or The Night of January 16th —which featured audience participation to determine the ending—the integration of technologies that allow audiences to make real-time choices during performances continues to expand. Emerging productions demonstrate how artists are reimagining the relationship between audience and performer through web-based interfaces, live polling, and gamified storytelling that invite viewers to become a part of the performance.

FREE TO PLAY

On September 20, 2025, Cole Schubert, presented his original show, Free To Play, at the Ellsworth Arts and Events Space. The production introduced a new form of immersive theater, merging live performance with interactive gameplay, in which audience members assumed control of characters’ actions in real time.

Figure 1: Poster for Free To Play. Source: Cole Schubert

Free To Play was a collaborative effort supported by the Frank-Ratchye STUDIO for Creative Inquiry through a $7,000 CS+X grant, highlighting the importance of community support in innovative arts projects. This roughly 90-seat black box performance reimagined the theater experience as a live “videogame,” combining narrative choice, gamification, and real-time audience participation.

Figure 2: Scene from Free To Play. Source: Fish Tank Theater Company

Technological Framework and Engagement

Central to Free To Play’s innovation was its technological infrastructure. The production’s tech-integration was inspired by the participatory energy of Twitch live streams and the economic mechanics of mobile gaming apps. The team sought to merge the immediacy of live theater with the dynamic interactivity of online platforms, enabling real-time audience influence on the performance.

To achieve this, the production utilized a Django Framework Python website that served as the show’s digital backbone, integrating live data management with audience engagement tools. It served as a database of current users including account information, purchase information, or time spent in the online store. The Django framework facilitated player registration but ultimately allowed admin to monitor live decision-making and commenting, to ensure easy and seamless audience experience.

Figure 3: Scene from Free To Play. Source: Fish Tank Theater Company

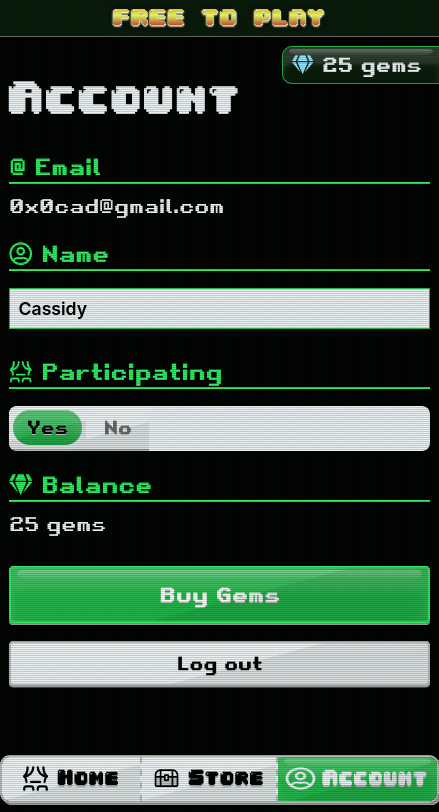

The website supported a customized online store where audience members could purchase “gems,” a fictional in-game currency inspired by mobile game microtransactions. These gems could then be exchanged for modifications, including narrative choices, add-on scenes, or aesthetic changes during the performance. This decision reflected financial and artistic components, highlighting how the game’s monetization structures creates a line between play, and alienating people from their money versus what their money was buying.

To maintain this illusion while keeping the user experience accessible, Cassidy Diamond, the production’s web designer, built a QR-based login system that allowed attendees to scan a code upon arrival, sign in via single sign-on through Google, and immediately participate through their phones. Diamond provides a detailed explanation of the website’s technical design, including how the code works, its features, and reflections from the show, in their GitHub article here.

Figure 4: Screenshot of the interface showing user account details. Source: GitHub Cassidy Diamond: 0xcad/free_to_play

Figure 5: Live gameplay and audience chat interaction during Free To Play. Source: GitHub Cassidy Diamond: 0xcad/free_to_play

Behind the scenes, the Django Framework maintained a live database of user activity, updating an admin dashboard monitored by a production team member during each show. This dashboard tracked purchases, moderated chat interactions, and relayed live updates to the stage manager, Anya Hilpert, For example, it notified Hilpert when an audience member had purchased the “dream ballet” sequence, prompting its performance in real time.

Transactions were processed through Stripe, ensuring secure and familiar payment handling while maintaining the illusion of digital currency. “I've just been feeling sort of out of control and not having agency in my use of my phone and my computer. I wanted to give the audience sort of control over that [agency] in the show and have this baseline theme of taking control over one's life and one's use of technology,” Schubert stated. The goal was not just to implement technology but to critically examine digital consumer culture, exploring how artistic and financial decisions intertwine in audience engagement.

Figure 6: Scene from Free To Play. Source: Fish Tank Theater Company

Similar videogame productions have been produced in other parts of the country. Dot’s Home Live is an innovative theater adaptation of the popular video game Dot’s Home, which follows Dot Hawkins, a young Black woman navigating her family’s history of housing and racial injustice.

Figure 7: Scene from Dot’s Home Live. Source: Dot’s Home Live. Photo by Shane Collins

The play translates the game’s moral-choice mechanics into a live, interactive experience by introducing a fourth-wall-breaking character, 4D, who pauses the story to address the audience and let them vote on key decisions. This participatory element means that each performance can unfold differently based on audience choices, blending gaming-style branching narratives with the immediacy and communal energy of live theater.

Compared to similar interactive frameworks, Free To Play leveraged gamification to a greater extent, allowing individual audience members to directly influence the narrative through choice-driven branching paths, in-show currency, and collectible mods. This further demonstrated how digital engagement strategies can be thoughtfully integrated into live theater while expanding opportunities for audience agency and participation.

Management and Workflow

Throughout development, Schubert managed communication between the artists, coders, and designers through a combination of Discord channels, email threads, and traditional production meetings, balancing the workflows of both theater and tech environments. The game and website were developed on parallel tracks and tested in small sessions to ensure stability when multiple users logged in simultaneously.

To prevent technical errors during performances, the team established safeguards and checkpoints within the game system. For example, the game designer, Lucia Shen, could temporarily block new audience inputs by pressing a key when dialogue was still unfolding or roll back to a previous point if a glitch occurred. These strategies not only minimized disruptions but also reflected the merging of software iteration and stage management, requiring Schubert to oversee both artistic cohesion and real-time technical performance within a single integrated workflow.

Figure 8: Backstage view. Source: Fish Tank Theater Company

From a management standpoint, Schubert approached evaluation through both creative and operational lenses. With each performance unfolding differently depending on audience decisions, success could not be measured by uniform outcomes but rather by the clarity and fluidity of the interactive experience. Post-show conversations with attendees served as a key feedback tool, revealing when the technology enhanced participation and when it caused confusion or disengagement. The production’s structure—where players could “fail” or even be replaced mid-show—offered an immediate indicator of how intuitive the system felt in practice.

As an independently produced work supported by a development grant, the project also functioned as a testing ground for future iterations, allowing Schubert to experiment freely with branching narratives, audience interfaces, and game mechanics before refining the balance between creative ambition and managerial control.

Audience Experience

From an audience member’s perspective, what did this all look like? Upon arrival, attendees took their seats and saw a projected livestream on stage. After scanning a QR code, they were directed to a web-based application where they entered their player names and gained access to familiar streaming features such as commenting and purchasing “gems.” These gems could be used to buy modifications including the dream ballet sequence, flute accompaniment, and a crowd favorite known as “doom scrolling guy”, all of which played out while the main storyline continued.

Figure 9: Performer on stage. Source: Cole Schubert

The experience blurred the line between spectator and performer. The host streamer, acting as the game’s narrator, used a random name generator to select audience members to join him at the front of the stage. Once chosen, participants entered the livestream and made on-screen decisions like “Wake Up” or “Go Back to Sleep,” triggering new settings such as a desk or kitchen. Each choice opened new pathways—some leading to major plot developments, others spiraling into humorous detours. Depending on the player, a turn could last anywhere from five to twenty minutes, with participants either pursuing the mission seriously or simply experimenting with the options available.

What made the production especially memorable was its unpredictability and the collective sense of play it fostered. As the story unfolded—from an initial race to save the protagonist from an apocalypse to sudden shifts involving divorce, corporate fraud, international conflict, and spontaneous karaoke duets—the audience became a part of the chaos. The laughter and participation of friends and colleagues created an atmosphere closer to a community game night than a traditional performance.

Figure 10: Scene from Free To Play. Source: Cole Schubert

Cultural Commentary and Artistic Evaluation

When asked if the production was a critique of mass media consumption or streaming culture, Schubert explained his increasing awareness of how easily technology and social media can lead to habits of uncontrol.

“ “By letting the audience take control of the narrative, deciding a character’s job, relationships, or even emotional outcomes, we wanted to mirror the tension between digital control and personal agency that defines how we interact with media today.””

By aligning form and content, the production integrated the mechanisms of engagement, choice, and influence present in both gaming and social media, while offering a playful, participatory reflection on agency.

Success was measured both creatively and operationally. Audience feedback, observation of player choices, and the seamless integration of technology into the performance indicated the effectiveness of the interactive design. Failures and glitches, when they occurred, were treated as learning opportunities, informing iterative improvements for future iterations.

Figure 11: Scene from Free To Play. Source: Cole

Free To Play, alongside works like Dot’s Home Live, demonstrates how theater continues to evolve. By integrating immersive technology, gamification, web-based interactivity, and active audience participation, in the Ellsworth Arts Space, the workshop production expanded the boundaries of engagement while offering a model for managing complex technological systems in live performance.

In doing so, Free To Play exemplifies a new paradigm of theater-making, where technological innovation and community collaboration reshape both production as well as artistic and audience experience.

For more information about the production, cast, and director, visit Fish Tank Theater Company.

-

A Host of People. "Dot’s Home 1." Accessed October 11, 2025. https://www.ahostofpeople.org/dots-home-1.

Babineau, Diana. "A Video Game Plays Out Onstage." Northwestern Magazine, Fall 2024. https://magazine.northwestern.edu/people/dots-home-live-show-video-game-theater-adaptation-wirtz-center-chicago.

Ellsworth Arts and Event Center. "Shadyside Pittsburgh's Home for Artistic Expression and Fun Events." Accessed October 9, 2025. https://www.ellsworthartspgh.org/.

Django Software Foundation. "Django: The Web Framework for Perfectionists with Deadlines." Accessed October 15, 2025. https://www.djangoproject.com/

Gruen, Adeline. “‘Clue: The Musical:’ An Interactive Experience.” Ruff Draft, April 4, 2023. https://ruffdraft.net/12276/opinions/clue-the-musical-an-interactive-experience/#:~:text=The%20whole%20musical%20is%20meant,musical%20is%20a%20bit%20different.

Hernandez, Alonso. "Behind the Scenes: Dot’s Home Live." PowerSwitch Action. April 25, 2023. https://www.powerswitchaction.org/updates/behind-the-scenes-dots-home-live/.

The Frank-Ratchye STUDIO for Creative Inquiry. "About." Accessed October 5, 2025. https://studioforcreativeinquiry.org/.

Schubert, Cole. "Free to Play." Fish Tank Theater Company. Accessed October 13, 2025. https://www.fishtanktheatercompany.com/free-to-play.

Stripe. "Stripe: Online Payments for Internet Businesses." Accessed October 13, 2025. https://stripe.com/?utm_campaign=AMER_US_en_Google_Search_Brand_Stripe_EXA-20839462206&utm_medium=cpc&utm_source=google&utm_content=720048964694&utm_term=stripe&utm_matchtype=e&utm_adposition=&utm_device=c&gad_source=1&gad_campaignid=20839462206&gbraid=0AAAAADKNRO7i124mEUHtM0k-llsxZNAqw&gclid=CjwKCAjwr8LHBhBKEiwAy47uUh8irG_YMNGD7ax-Jq9x6xkZ7gPIqO9exe19r3JAU8KpU0vsqLx3WhoCIf8QAvD_BwE

0xcad. free_to_play. GitHub repository. Accessed October 15, 2025. https://github.com/0xcad/free_to_play.