By Ziqi Xiang

Spoiler Alert: This article contains detailed discussions of major plot points, character growth, and specific scenes from Hamnet.

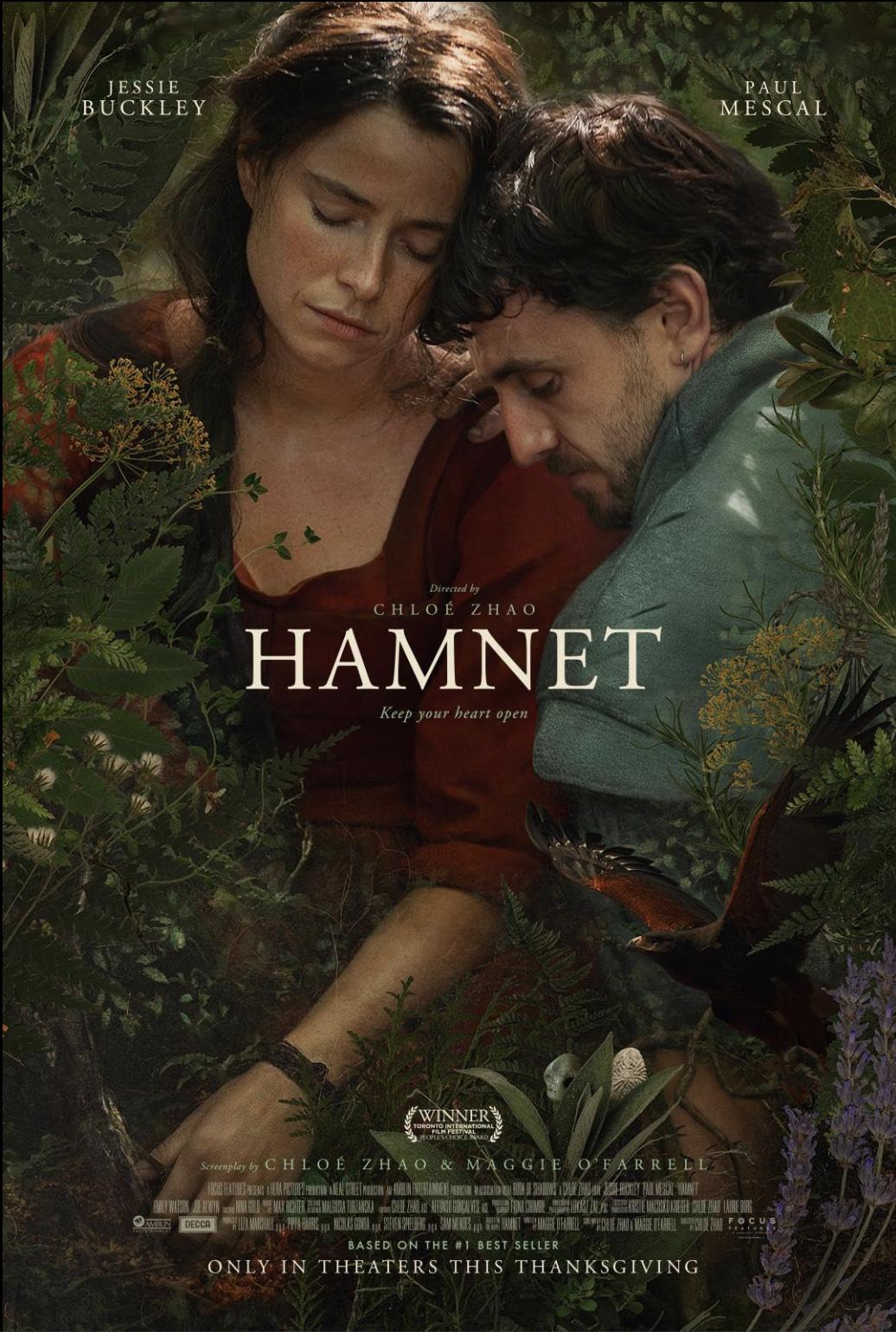

Figure 1: Hamnet 2025 - official poster. Source: IMDb

I watched Hamnet twice during the holiday season. In the first viewing, I was swept away by surging emotions and moved to tears; in the second, I was still deeply affected but had more space to attend to Chloé Zhao’s cinematic language and expressive strategies. The emotions that flooded the theater were layered, complex, and difficult to articulate. Although the joys and sorrows of human life, along with their aesthetic sublimation through art, are already profoundly moving, I sensed something even more primal and deep beneath this emotional intensity—an underlying compassion and synesthetic resonance rooted in hidden strata. This intuition stirred my desire to unravel Zhao’s mode of expression.

Agnes was born into a forest witch family in the countryside of Stratford in sixteenth-century England. This origin marked her simultaneously as marginalized and as intimately connected to nature. Skilled in herbal medicine and falconry, she seemed able to communicate with mountains, plants, animals, birds, and insects. Taught by her mother to attend to dreams, she could foresee the future; by grasping between a person’s thumb and index finger, she could glimpse their fate. The English countryside of the sixteenth century was damp and animistic, still enjoying a tranquility not yet claimed by capitalist market logic or the large-scale production of the Industrial Revolution. A young Latin teacher, struggling to sustain his family’s leather workshop, encountered Agnes deep in the forest. At a shadowy cavern that seemed to lead simultaneously toward life and death, he told her the story of Orpheus and Eurydice.

Figure 2: Agnes Beneath the Forest’s Hollow. Source: Movie Insider

For Agnes, in this natural hollow that resembled an entrance to the underworld, she heard within the story of the tunnels, oceans, and undiscovered countries. Through the rhetoric of myth, she encountered, for the first time, the concepts of love and death. In terms of my argument, this moment marks Agnes’s initial exposure to the symbolic order produced by rhetoric—her transition from a pre-linguistic state of holistic perception of nature into the symbolic system woven by human language. Before this, as a “forest witch,” she existed prior to interpretation; more precisely, she functioned as a translator of natural perception. Coexisting with the forest, she had not yet separated herself from it as a distinct “human” subject—until the Latin teacher, a natural agent of the symbolic system, guided her toward the bifurcating paths of the human world.

Yet this was only the beginning of the story. During her first childbirth, Agnes returned alone to the cavern. (Jessie Buckley delivers a performance that is primal, astonishing, and charged with overwhelming vitality. ) Agnes’s bond with the forest still endured: heaven and earth became her birthing chamber, the humus her bed, and the cavern—like the womb of the earth—brought forth her child.

Many years later, when the hawk she had trained in her youth died, she returned once more to the cavern. With stones and woven grasses, she commemorated her fated separation from nature. Thereafter, the void of the deep hollow gazed at her only in dreams; the red honeysuckle berries pointed toward a passage that was both return and final destination—an entrance to the netherworld.

While raising her eldest daughter Susanna, Agnes suggested that Will leave rural Stratford for London to pursue greater opportunities. Unable to endure the oppressive family atmosphere and his abusive father, Will agreed. While he was preparing a new play in London, Agnes underwent her second childbirth on a stormy evening. In unbearable pain, she longed to return to the forest cavern, but flooded streets and her family’s persuasion forced her to remain at home, where she gave birth to Hamnet and a breathless Judith. Perhaps Agnes’s powerful will surpassed the absent blessing of the forest, for Judith ultimately released her first cry in Agnes’s arms.

As Agnes gradually drifted away from the forest of her past and entered the worldly responsibilities of motherhood and marriage, she also experienced moments of happiness. Yet the intensity of her emotional bonds left her utterly devastated when the plague claimed Hamnet’s life. The sensations of childbirth and bereavement intertwined, with sensory shock preceding language.

Figure 3: Agnes in the New Family House. Source: Focus Features

Generations of forests and maternal lineage had taught Agnes how to perceive nature and her body, how to foresee the future and avert misfortune; yet before the torrent of pain that defied interpretation, she was rendered powerless in speech. Unable to metabolize her grief, she gradually sealed off her inner world—her perceptual faculty. Her gaze became vacant, her attitude toward life increasingly cynical, even resentful of her husband’s absence, until the moment she entered the theater for the premiere of Hamlet.

Figure 4: The Stage Design of Hamlet in Chloé Zhao’s Hamnet (2025). Source: Focus Features

The ruthless Shakespeare offered his painstaking tragedy. Agnes, in her fury, could not accept the symbolic appropriation of her private suffering: the forest on the stage backdrop was artificial, just as the genuine grief of her soul was violated by a poet’s rhetoric. The perceptual capacity she had once relied upon, now sealed away, was excavated and exposed by her husband from the depths of memory—yet she simultaneously recognized, in the casting and visage of Hamlet, the familiar figure she had long mourned. Gradually she entered the emotional current of the drama with the audience; the untranslatable pain that preceded language finally flowed from her sealed heart, like childbirth. When Hamlet fell in the final act, she reached out her hand, offering to the foreign prince the commiseration that a mother who has lost a child could only extend. The three hundred spectators reached out their hands as well. Plague and death spread across the European land; mourning and honor filled every seat and worldwide theaters yet to come. Agnes finally realized that she did not have to bear this pain alone.

Although the film’s theme is clearly framed as the story of a family losing a child, what Chloé Zhao ultimately seeks to convey is far more intricate. She mobilizes abundant and authentic emotions, interwoven with myth and ritual, to evoke the deepest strata of human experience—an affective realm that is inherently ambiguous, in which every viewer may encounter their own Hamnet. In a recent interview, Zhao reflected on Carl Jung’s enduring questions: “Who are we?” and “What role do we play in life?”, suggesting that mythology offers a path to find meaning: “Stories exist so we can see a pantheon of journeys and explorations and find that meaning,” as she puts it.

Zhao’s narrative and imagery, together with the cinematography of Łukasz Żal, unfold with a rhythm rooted in myth, interweaving like parallel worlds perceived through Agnes’s and Will’s gazes. Their perspectives glance back at one another until they finally converge at the film’s end: nature appears sacred and distant, sensation immersive and embodied, like Orpheus unable to resist turning back toward Eurydice, only to meet the gaze she had long awaited.

In the same interview, Zhao also suggests that Western civilization, shaped by Plato and Aristotle, has long suppressed its mystical origins. Yet, she observes, there is today a renewed collective desire for mystery, ambiguity, and poetic language. Before encountering Will’s mythic world, Agnes inhabits such a pre-linguistic mode of existence—a state that Zhao herself seeks to imagine when she asks "how did they(early mystics) learn about our world" before reason and linear narrative took hold. Agnes’s life in the forest thus contemplates a speculative return to an epistemology prior to rational discourse, where perception precedes language and meaning emerges from sensation rather than logic.

It is along this trajectory that the film’s narrative unfolds. The narrative flows organically as literary symbols and motifs succeed one another: we traverse the pre-linguistic space of Plato’s cave; we enter myth as a symbolic system; we are cast into motherhood and domestic life; we encounter the Lacanian Real that resists symbolization; we witness the theft of aura and the poet’s backward glance as an act of betrayal; and finally, we observe artistic sublimation as a belated ethical and meaningful container.

Figure 5: Collective Mourning in the Theater. Source: Focus Features

Before arriving at any conclusion, I want to articulate my most intuitive understanding of—and respect for—Zhao’s resistance to interpretation and symbolic obsession, which may be, if anything, the film’s quiet center. In numerous interviews, Zhao has expressed her desire to lead us back to the fragility and interiority of our own being. One senses that she herself has already traversed this journey: from unutterable pain, fear, and anxiety toward a form of artistic sincerity and humility. It is from this inner world that she ultimately draws strength, learning to hold her own feelings that are not much different from the anguish of others, weaving her own stories to find the meaning of one’s life, as Carl Jung once questioned.

When Zhao first received the Oscar for Nomadland, quoting the Confucian classic: “People at birth are inherently good. (人之初,性本善。[Rén Zhī Chū, Xìng Běn Shàn])” Though this phrase has often been distorted into an instrument of ideological discipline, it is also what I perceive in Hamnet: the sincerity and wholeness of human beings prior to language and symbolic systems, within the most primordial experiences of life. When pain is so direct and truthful that it resists assimilation, we are fortunate to have art as a refuge—as a buffer within the symbolic order—through which we contemplate life. This is both the limitation of our contemporary condition and, perhaps, our ultimate reconciliation.