TikTok, a Chinese-owned social platform catered to sharing short-form videos, has been seeing a fair share of media and governmental attention as of this summer. This is largely due to the app seeing an increase in user base since the beginning of the COVID pandemic and calls from authority figures for the app to be banned due to perceived national security threats (Business Insider). Due to the rapid development behind the app’s popularity and security allegations, arts and entertainment managers may have a variety of questions surrounding this platform. So, does TikTok pose enough of a security risk to warrant a ban or shift to American ownership? In this article, we will dive into the history of the platform to provide a complete view of the app as a whole.

TikTok Timeline

2017

TikTok’s parent company, ByteDance, purchases the Shanghai-based app Musical.ly for $800 million (Hollywood Reporter). Musical.ly was a short-form video sharing platform, which originally was developed as an educational tool but eventually was known for lip-syncing and dancing videos. At this time, Tiktok and Muscial.ly had yet to be merged into a single interface.

2018

Muscial.ly is officially shut down and its users are switched to the TikTok app. In the process, “users [were] automatically signed up for the new TikTok app, which [included] upgraded features from both products. Follower counts and past posts [were not] impacted by the change” (Hollywood Reporter). This strategy allowed TikTok to retain the same community that Musical.ly had gained over the 3 years of its operation, containing around 100 million monthly users. This audience, while already pre-formed and loyal, did come with complications that would follow TikTok throughout its existence. This is due to TikTok users’ relatively young ages, which has caused problems similar to those of its forerunner. Musical.ly “faced challenges as it has tried to monetize through advertising because of the young age of its core users. Although the app requires users to be at least 13 to join, past reports have suggested that many were in grade school” (Hollywood Reporter).

Later on, Tiktok faced a ban in Indonesia after the government concluded that the app contained “pornography, inappropriate content and blasphemy” (New York Times). This ban was lifted a week later after Tiktok agreed to remove negative content from the platform and built a location in Indonesia. This is similar to what Tumblr, a U.S.-operated blogging website, was forced to enact on December 17 of the same year after Apple took the app off their store. Afterward, Tumblr users were “not allowed to post any not-safe-for-work (NSFW) content: that includes nudity, pornography, and media showing ‘real-life human genitals or female-presenting nipples’” (Business Insider). Thus, TikTok is following similar strategies to U.S. companies when faced with regulatory requests.

February 2019

TikTok pays a $5.7 million dollar fine after the FTC investigated Musical.ly and had “uncovered disturbing practices, including collecting and exposing the location of young children. Despite receiving thousands of complaints from parents, the company failed to comply with requests to delete information about underage children and held onto it longer than necessary” (CNN). In response, TikTok revamped the user experience for its younger US audience by creating “a ‘separate app experience’ for younger U.S. users in which they ‘cannot do things like share their videos on TikTok, comment on others' videos, message with users, or maintain a profile or followers’” (CNN). Google faced similar fines in 2019 as well, after the FTC charged them with a fine of “$170 million following the agency’s investigation into YouTube over alleged violations of a children’s privacy law” (The Verge). This fine overtook TikTok’s as the largest fine relating to COPPA (the Child’s Online Privacy Protection Act[m4] ). As a result, Google was required to put policies into place that mirrored Tiktok’s, “requiring creators to label content intended for younger audiences and halting the data collection on videos clearly targeting minors” (The Verge).

April 2019

As with Indonesia in 2018, India temporarily banned TikTok after “A court in the southern Indian state of Tamil Nadu asks the Indian federal government to ban downloads of TikTok, which it said encouraged pornography” (New York Times). The ban lasted two weeks before TikTok successfully appealed the decision. (CNN). As time progresses, TikTok seems to be navigating the legal systems of countries that the app operates in two ways, either to comply with the law as it did in Indonesia or to challenge orders that may not be legally sound as it did within India.

November 2019

The U.S. federal government launched an investigation into TikTok as a national security threat. The Committee on Foreign Investment (CFIUS) leads this charge, looking into the acquisition of Musical.ly by TikTok. The reasoning behind this investigating was “because Bytedance did not seek clearance for the acquisition [of Musical.ly] at the time, the committee was able to launch a post-deal probe” (BBC). This investigation is similar to that in which CFIUS did not allow the sale of Grindr, an American dating app catered toward men attracted to men (or gender-nonconforming individuals attracted to those that identify with the male gender), to Chinese investors. Before either of these cases was the instance of the CFIUS not allowing Chinese-owned phone manufacturer Huawei from interacting with American companies all together. TikTok and Grindr are special cases when compared to Huawei, as “Phone networks are a long-standing point of national security interest, and the government has long played an active role in the system as a result. But none of that is true of consumer apps on consumer phones” (The Verge).

April 2020

After seeing a surge of downloads as a result of pandemic-caused quarantine, TikTok reaches 2 billion downloads. The app begins to outperform Instagram in terms of downloads (Business Insider).

May 2020

To underscore its independence from China, ByteDance recruits former Head of Streaming at Disney, Kevin Mayer, as COO and CEO of TikTok (CNN). This decision was also the result of ByteDance’s desire better serve a complex international market. The company plans to “ramp up its expansion plans for TikTok and further boost its international presence. Moreover, Mayer could help ByteDance address barriers hindering the app’s global expansion” (TechinAsia).

June 10, 2020

The Netherlands opens an investigation into TikTok’s child data protection policies forcing EU regulators to view the app through a more cautious lens. (New York Times).

June 29, 2020

India bans TikTok from the 200 million users within the country for an indeterminate amount of time. This action was a part of a blanket ban of dozens of Chinese-owned companies put into effect after a “violent border clash between India and China left at least 20 Indian soldiers dead” (CNN). While the app maintains popularity and positive reviews from its Indian user base, there were “public appeals for a boycott of Chinese products” after the attack, showing that the general Indian population was supportive of the ban (CNN). There are hopes for the app to return to India at some point in the future, once tensions are alleviated. One avid Indian TikTok user, Jaya Lall, reasons that “What they [China] are doing is wrong [referring to Indian/Chinese military conflict] … We are happy that ... the ban happened but still we have a hope that [TikTok] will come back, we are waiting for it”(CNN).

July 6, 2020

TikTok pulls its operations out of Hong Kong after the city passed a national security law granting elevated powers to the mainland Chinese government. This happened shortly after “several tech companies such as Google and Facebook have suspended processing government requests for user data from the region … the recent law would let mainland China request for user data from global companies with operations in the special administrative region” (TechinAsia). The implication of such an action helps to display that while TikTok has had data privacy concerns in the past (that are comparable to the concerns of U.S.-lead companies), the company is willing to take actions to protect the data of its users from the Chinese government, despite being a Chinese-based company.

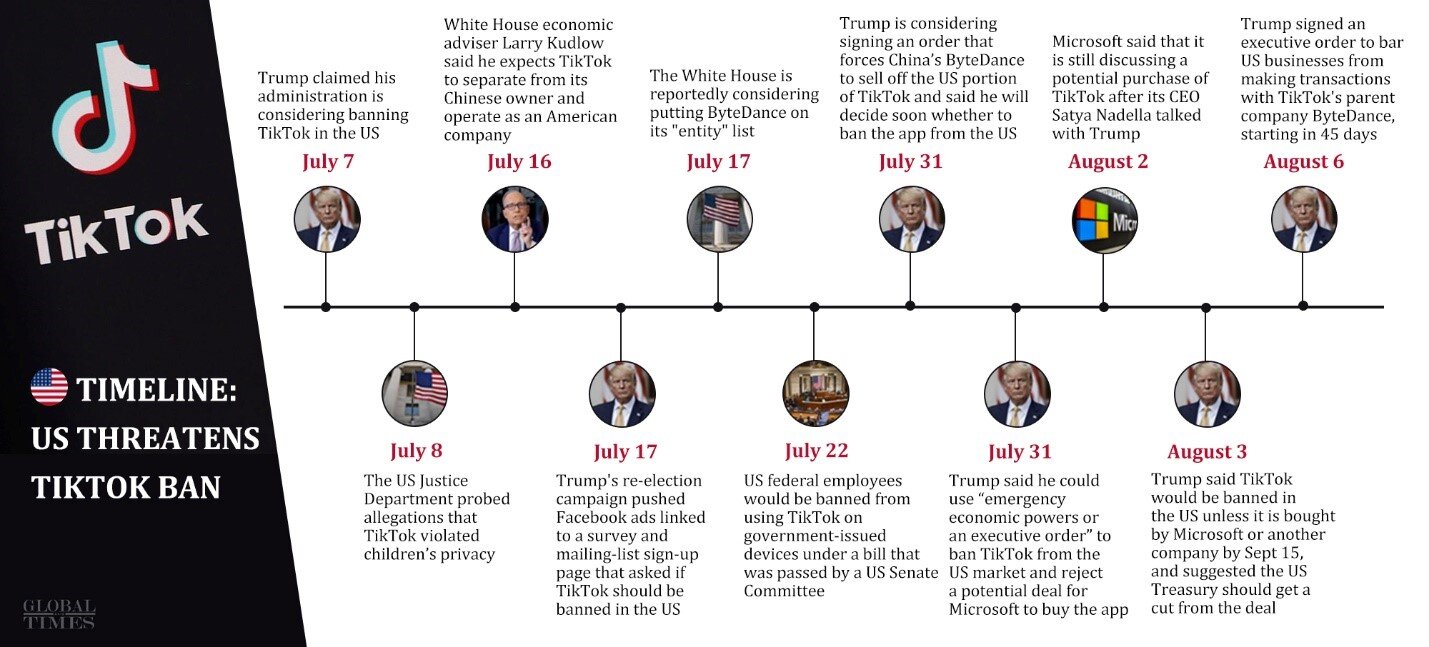

Figure 1: Visual Time Line Solely Focused on the Development of an American TikTok Ban. Source: Global Times.

July 7, 2020

The Executive Branch of the United State begins to publicly speak out against TikTok, with a ban being considered. Notably, Secretary of State Mike Pompeo stated that there are concerns that U.S. citizen data can fall “in the hands of the Chinese Communist Party" (New York Times). Additionally Donald Trump has reasoned that a ban could “punish China for the outbreak of the coronavirus” (New York Times). These worries also branch into the Legislative branch, where “the Senate voted unanimously to ban federal employees from using TikTok on government devices” (Vox).

However, these worries over U.S. data being collected by the Chinese government have yet to find roots in completed or published reports. On the other end, “a recent CIA assessment obtained by The New York Times found no evidence that the app [TikTok] had been used by Chinese spy agencies to intercept data” (The Verge). Bytedance has also taken the position of not surrendering user data if approached by the Chinese government. Measures taken by the company include “that it [TikTok] doesn’t store user data in China and that it rejects any requests made by the Chinese government to censor content or to access TikTok’s user data. The app is also designed so it won’t be accessible by mainland China, where ByteDance operates Douyin, the Chinese version of TikTok” (TechinAsia). Rejecting requests from the Chinese government is a bold stance for the company to take, since “the Chinese National Intelligence Law of 2017 says any Chinese company can be drafted into espionage, a company could be forced to hand over the data” (Vox).

July 20, 2020

Australia scrutinizes TikTok as a potential risk for foreign interference and privacy concerns (New York Times).

July 29, 2020

Japanese lawmakers take steps to “urge the government to take steps to limit the use of TikTok, concerned that user data may end up in the hands of the Chinese government” (New York Times).

August 2, 2020

Microsoft pursues the possibility of purchasing TikTok's U.S., Canadian, Australian and New Zealand services. It is reported that “the company is looking to complete the discussions by September 15” (TechinAsia).

August 4, 2020

Australian Prime Minister Scott Morrison announces that “Australia has found no evidence showing it should restrict TikTok” (New York Times). This shows that investigations from two different countries (Australia and the United States) have come back with the result that TikTok does not pose more of a security risk than social platforms owned outside of China.

August 6, 2020

Trump signs an executive order to that gives “ByteDance 45 days to sell TikTok to an American company” (Vulture). Initially, Trump leaned heavily in favor of a complete ban of the app, but shifted his opinion after the discussion of a number of factors. The timeline of this perceived change is as follows: “On July 31, he [Trump] was adamantly opposed to a U.S. company buying TikTok, in favor of an all-out ban, but on Monday, August 3, he was all for it, with the caveat that ‘a very substantial portion of that price is going to have to come into the Treasury of the United States’” (Vulture). Another perspective behind this change could be due to advisement from his staff and other Republican politicians due to beliefs that “banning TikTok would trigger a wave of legal challenge as well as alienating young voters ahead of November's presidential election” (Business Insider).

The rationale behind this order is rooted in concerns over the United States’ data privacy and the potential for censorship on the TikTok platform. Part of the order states, without references to empirical evidence, that TikTok “automatically captures vast swaths of information from its users [and] … threatens to allow the Chinese Communist Party access to Americans’ personal and proprietary information — potentially allowing China to track the locations of Federal employees and contractors, build dossiers of personal information for blackmail, and conduct corporate espionage” (Vox). The executive order also cites concerns over how the app could “censor political speech and spread misinformation that could hurt democracy in the U.S.” (Vox). But exactly how valid are these claims?

In terms of data collection and privacy, TikTok, like other social media apps, does collect data from users. However, as discussed before, this data is stored on United States servers and the TikTok brand does not currently operate in China. When looking at the fine details, “TikTok automatically collects reams of user data, including location and internet address, searching history within the app, and type of device being used, according to its privacy policy. But many other popular social media apps do this, too … TikTok has said that it collects less data than its competitors, like Facebook and Google, because it doesn’t track user activity across devices, which both companies do” (Vox).

Turning to the accusations of censorship guided by the Chinese government, like most social platforms, TikTok does have a user agreement that consumers are required to adhere to. If violated, content can be removed and users can face repercussions. However, “these guidelines [are] part of broad rules against controversial discussions on international politics across countries, so there’s no explicit proof that this was a directive from the Chinese government to TikTok” (Vox). In short, this shows that moderation policies put into place by TikTok have been made on a company level, rather than enforced on the company by the Chinese government.

August 7, 2020

TikTok responds to the Executive Order with shock. In a statement the company explains that “For nearly a year, we have sought to engage with the U.S. government in good faith to provide a constructive solution to the concerns that have been expressed. What we encountered instead was that the Administration paid no attention to facts, dictated terms of an agreement without going through standard legal processes, and tried to insert itself into negotiations between private businesses” (Vulture). The company goes on to shine skepticism on the claims of the executive order and drew similarities between their business model and the models of other U.S.-owned tech companies. As stated, “the recent Executive Order … was issued without any due process. The text of the decision makes it plain that there has been a reliance on unnamed ‘reports’ with no citations, fears that the app ‘may be’ used for misinformation campaigns with no substantiation of such fears, and concerns about the collection of data that is [the] industry standard for thousands of mobile apps around the world” (Forbes).

August 8, 2020

TikTok discusses their plans to sue the current presidential administration over the legality and legitimacy of the executive order, as soon as August 20. The lawsuit will take place in the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of California. “The lawsuit will argue that President Trump's far-reaching action is unconstitutional because it failed to give the company a chance to respond. It also alleges that the administration's national security justification for the order is baseless” (NPR). The implications of the Executive Order’s ban would severely limit TikTok’s ability to challenge the order due to the inclusion of United States businesses not being allowed to do business with the company. Notable impacts relating to this detail include “TikTok's more than 1,000 U.S.-based employees could have their paychecks indefinitely frozen. It could force landlords housing TikTok operations to evict them. And Trump's order could make it impossible for American lawyers to represent TikTok in any U.S. legal proceedings” (NPR).

Even if United States businesses were to attempt to do business with TikTok under the rule of this order, the punishments would be severe. Such consequences are “a $300,000 fine per violation … ‘willful’ offenders could even face criminal prosecution” (NPR). Due to the executive order being issued under the International Emergency Economic Powers Act, there are certain avenues TikTok can take to prove that the executive branch overstepped its rightful power. TikTok can argue that “the authority [of the IEEPA] cannot be used to regulate or prohibit either "personal communication" or sharing of film and other forms of media. If Congress believes the president has used the emergency economic powers unjustly, lawmakers can overrule the order by passing a resolution that would terminate the order” (NPR).

As of the writing of this article, no formal lawsuit has been put into place. In the event that a suit is not filed (or the suit fails) TikTok still has until September 15 before the Executive Order takes effect to sell its U.S. assets or to cease operation completely. This series of events is far from over, but the outcome could set some significant precedent with respect to foreign-owned technology services. As a result, international arts and entertainment organizations will have to take these changes into consideration whenever trying to implement or share innovative technology in their daily operations or other aspects of the business.

RESOURCES

Allyn, Bobby. “TikTok To Sue Trump Administration Over Ban, As Soon As Tuesday.” NPR. NPR, August 8, 2020. https://www.npr.org/2020/08/08/900394707/tiktok-to-sue-trump-administration-over-ban-as-soon-as-tuesday.

Brandom, Russell. “Trump's TikTok Ban Is a Gross Abuse of Power.” The Verge. The Verge, August 11, 2020. https://www.theverge.com/2020/8/11/21363405/trumps-tiktok-ban-legal-corruption-free-speech-china.

Cordon, Miguel. “TikTok to Exit Hong Kong, Report Says.” Tech in Asia - Connecting Asia's startup ecosystem, July 6, 2020. https://www.techinasia.com/tiktok-exit-hong-kong.

Ghaffary, Shirin. “Do You Really Need to Worry about Your Security on TikTok? Here's What We Know.” Vox. Vox, August 11, 2020. https://www.vox.com/recode/2020/8/11/21363092/why-is-tiktok-national-security-threat-wechat-trump-ban.

Hamilton, Isobel Asher. “TikTok Is at the Heart of a Wild Geopolitical Dogfight and It Could Result in Microsoft Buying TikTok. Here's What's Going on.” Business Insider. Business Insider, August 3, 2020. https://www.businessinsider.com/timeline-tiktok-microsoft-potential-acquisition-2020-8.

Haylock, Zoe. “TikTok Has 45 Days Until ... What, Exactly?” Vulture. Vulture, August 7, 2020. https://www.vulture.com/2020/08/tiktok-ban-usa-explained.html.

Haylock, Zoe. “TikTok Has 45 Days Until ... What, Exactly?” Vulture. Vulture, August 7, 2020. https://www.vulture.com/2020/08/tiktok-ban-usa-explained.html.

Iyengar, Rishi. “This Is What It's like When a Country Actually Bans TikTok.” CNN. Cable News Network, August 13, 2020. https://www.cnn.com/2020/08/13/tech/tiktok-ban-trump-india/index.html.

Jarvey, Natalie. “Musical.ly Owner Merges App With TikTok.” The Hollywood Reporter, August 2, 2018. https://www.hollywoodreporter.com/news/musically-owner-bytedance-merges-app-tiktok-1131630.

Kelion, Leo. “TikTok: How Would the US Go about Banning the Chinese App?” BBC News. BBC, August 3, 2020. https://www.bbc.com/news/technology-53621492.

Kelly, Makena. “Google Will Pay $170 Million for YouTube's Child Privacy Violations.” The Verge. The Verge, September 4, 2019. https://www.theverge.com/2019/9/4/20848949/google-ftc-youtube-child-privacy-violations-fine-170-milliion-coppa-ads.

Leskin, Paige. “A Year after Tumblr's Porn Ban, Some Users Are Still Struggling to Rebuild Their Communities and Sense of Belonging.” Business Insider. Business Insider, December 20, 2019. https://www.businessinsider.com/tumblr-porn-ban-nsfw-flagged-reactions-fandom-art-erotica-communities-2019-8.

Pham, Sherisse. “TikTok Hit with Record Fine for Collecting Data on Children.” CNN. Cable News Network, February 28, 2019. https://www.cnn.com/2019/02/28/tech/tiktok-ftc-fine-children/index.html?ofs=fbia.

Reuters. “Timeline: TikTok's Journey From Global Sensation to Trump Target.” New York Times. New York Times, August 5, 2020. https://www.nytimes.com/reuters/2020/08/05/business/05reuters-usa-tiktok-timeline.html.

Robertson, Adi. “How the Trump Administration Could 'Ban' TikTok.” The Verge. The Verge, July 9, 2020. https://www.theverge.com/2020/7/9/21315983/trump-pompeo-ban-tiktok-bytedance-chinese-social-media-national-security-censorship-methods.

“Timeline: US Threatens TikTok Ban.” Global Times, August 7, 2020. https://www.globaltimes.cn/content/1197030.shtml.

Togoh, Isabel. “TikTok 'Shocked' Over Trump's Executive Order Against The App, Warns It Might Go To Court.” Forbes. Forbes Magazine, August 7, 2020. https://www.forbes.com/sites/isabeltogoh/2020/08/07/tiktok-shocked-over-trumps-executive-order-against-the-app-warns-it-might-go-to-court/.

Yu, Doris. “Timeline: How TikTok Reached Global Fame and Now Faces a US Ban.” Tech in Asia - Connecting Asia's startup ecosystem, August 6, 2020. https://www.techinasia.com/timeline-tiktok-reached-global-fame-faces-ban.

———. “Trump Issued an Executive Order Effectively Banning TikTok If It Doesn't Sell in the next 45 Days.” Vox. Vox, July 31, 2020. https://www.vox.com/recode/2020/7/31/21350072/trump-tiktok-executive-order-ban-microsoft-sale-bytedance-china-security-concerns.