Figure 1: Demographic Breakdown of Fan Convention Attendees. Source: Author.

In 1992, Henry Jenkins published Textual Poachers, his first written observations of the formation of fan communities and the participatory nature that surrounds the subculture. This publication helped to open the door for academic communities to explore fan studies: observing how fan communities form and the rationale behind their motivations. Over the span of three decades, aca-fans (academic fans) have explored the economic, social, and psychological impacts of the fandom subculture in both pre-digital and digital ages.

The value of fandom has received gradual attention from industry players after the collective power of fandom has been observed to make or break arts or entertainment projects. A 2016 Variety survey found that “85% of those surveyed reported being fans of something – 97% in the 18-24 age range” (Kresnicka). Fan events and conventions have also seen extensive growth and over time have become a ninety-million-dollar industry in the U.S.. San Diego Comic Con, which debuted in 1970 with 300 attendees, now sees up to 150 thousand fans annually. (Schulman). This cultural shift displays why data-driven strategies are now targeting “fans” rather than “audiences” or “viewers.” However, there hasn’t been an effective method for viewing and interacting with these communities on digital platforms.

This lack of understanding can be attributed to both the historic cultural norms of fandom and the new digital tools that fans use to connect online. These digital tools reinforce previously held practices of fan activity (such as enhancing the presence of gift economies), but also disrupt how fandoms form by granting global reach and enhancing fans’ ability to collaborate as a unified force. Such examples include the use of the internet for fans of CW’s The 100 to organize and donate $121,000 to the Trevor Project after the death of a major queer character and for fans of NBC’s Chuck to prevent the show’s cancellation by organizing an eat-in at Subway, one of the studio’s major advertisers. (Booth). Technology enhances the power of fan groups by expanding the range of fan activities over various digital platforms and creating social networks that promote engagement and collaboration. These emerging traits encourage a decentralized, transmedia experience between content creators and fandom participants that is mutually beneficial. However, this experience requires a reciprocal understanding of producer/fan relationships. Without such an understanding, there exists a paradoxical relationship where the success of the content creator is dependent on fans, but without access to fan resources, content creators are unable to understand what attracts fannish behaviors and loyalty. As such, using digital tools to collect data on online fan communities and to visualize the data can help managers facilitate and strengthen their connection with target audiences.

Research Goal

With the emergence of digital fan engagement, fan codes and traits that were once hidden to content makers are now able to be studied on an individual and collective scale through scraping and network mapping. This paper explores how to access information in order to understand fan behavior and the best ways to cultivate fan/producer relationships. While this study focuses on film and television, this information can be used to map digital conversations and communities surrounding all artistic mediums. Managers can use information gathered from online communities to gauge sentiment towards an institution, how to strategically approach marketing to different audiences, and utilize fan/producer relationships to drive consumer behavior. We approach this goal through the following research questions:

1. What is fandom?

2. Where does fandom exist?

3. How do Content Makers find fandom spaces?

4. What can Content Makers do to derive value from fan activity?

Defining Fandom

Because fan studies are a relatively new discipline, there is no common definition of fandom. This can be attributed to the disparity between diversity of individual fan behavior and the collective agency of a fan community. Different fandoms offer different experiences across various platforms and types of media, while maintaining a co-habitual environment that allows for shared emotional connections between the nodes of the network. Despite this relationship, there are a collection of traits that aca-fan scholars have agreed are commonplace among fandoms: participatory culture, gift economies, and intermediate social spaces (Subculture and Sociology).

Participatory Culture

Due to the importance of social and emotional validation in fandom spaces, most fandoms organize through a “participatory culture.” Participatory culture, in contrast with consumeristic cultures, involve fans creating and producing media directly related to the content they consume. This affective behavior is the result of excess fannish energy and the emotional desire to contribute to the object of a fan’s affection. Jenkins (1992) describes participatory cultures to have the following attributes:

1. Relatively low barriers to artistic expression and civic engagement

2. Strong support for creating and sharing one’s creations with others

3. Some type of informal mentorship in which the most experienced members pass along their knowledge to novices

4. Members who believe their contributions matter

5. Members who feel some degree of social connection with one another and care about other members’ opinions about their contributions

In digital applications, there are many diverse modes of engagement that fans can use to participate, ranging from low levels of investment like sharing a post to high levels of investment like organizing a wiki to catalogue fandom knowledge. These modes of engagement vary across digital platforms that fans utilize, including social media, fan-made websites, fan work content-sharing sites (such as fanfiction websites like Archive of our Own), official sources, and fan information sites (such as wikis). This range of engagement allows for fans of different skill sets to contribute in different ways that ultimately benefit the community. The collective act of creating, indexing and distributing fan media helps to identify like-minded peers and establish comraderies around compatibility of interests.

The variety of skills that fans can use to contribute to the community have different applications in fan/producer relationships, with some skills being acceptable to be displayed publicly while others are expected to remain private (out of sight of producers). Lynn Zubernis and Katherine Larsen, authors of Fandom at The Crossroads: Celebration, Shame and Fan/Producer Relationships categorize these skills into three categories: technical, analytical, and interpretive. In digital fandom, fans can migrate across platforms and decide their degree of participation within each skill.

Figure 2: Chart describing participatory actions in fan communities. Source: Fandom at The Crossroads: Celebration, Shame and Fan/Producer Relationships, 2013

Gift Economies

Fan communities operate heavily under a gift economy, reliant on the reciprocation of labor and skills between members of the fandom. These gifts help to create the social structure of fandom. Karen Hellekson attributes this behavior to pre-digital fandom behavior in a 2015 edition of the Cinema Journal, “This gift culture is a remnant of the fanzine era, when a desire to fly under the radar of the copyright owners led to ‘no infringement intended, no profit made’ statements in headnotes of fan creations and set tenor of engagement with producers.” In this economic model, value is derived from the time, effort, or skill used to create a gift and exchanges are characterized by giving, receiving, and reciprocating. (Turk).

The nature of this system has led to some fan communities reacting poorly to producers or fellow fans try to profit off fan works. This outrage can be seen through fandom criticism of Fifty Shades of Grey (which originally was posted as Twilight fanfiction online) and Disflix (a program meant to teach influencers how to monetize fan participation in the Disney fandom). The Journal of Transformative Works and Cultures provides further explanation as to why monetization done poorly will face fan backlash, “Although it was marketed as a community-building service, Disflix was also conceived as a platform to teach subscribers how to be popular and money-making Disney fans. … The biggest criticism of Disflix's subscription-service model was what it would mean for other fan-run accounts that provide content for free and make their money through ads or sponsorship deals” (Kiriakou). Monetization of fan behavior can be fruitful, but it requires the understanding of the fandom’s degree of acceptance, the organic growth of pro-commerce attitudes from within the community, and the reciprocal effects on the overall community.

Intermediate Social Spaces

Another trait that has translated from pre-digital to digital fandom is the construction of barriers between social extremities, creating an intermediate “safe” space for fandoms to occupy and engage in collective self-expression. Larsen and Zubernis rationalize these barriers, stating, “Because fans participate in a variety of ways, they must constantly negotiate and renegotiate boundaries, stepping back and forth between public and private spaces. Some fan practices are mainstream enough to make public spaces comfortable, while others are not” (Larson and Zubernis 16). These barriers vary from fandom to fandom and platform to platform and are typically forms of self-censorship put into place to protect the subculture. Straying too far toward either extremity could violate the integrity of the intermediate space that attracts fannish behaviors, impacting the degree of participation. Due to the nature of these boundaries, fans are most likely to speak about the various positions of the fandom within the community while being wary of outside influences. This makes the degree of betweenness difficult to see from outside fan communities, making the knowledge of internal networks a necessity. Examples of intermediate environments that fandoms occupy include:

Private----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------Public

Open boundaries -------------------------------------------------------------------------Closed boundaries

Mass Culture ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------Popular Culture

Individual participation -----------------------------------------------------------Collective participation

Equal Ownership-------------------------------------------------------------------------Central Ownership

Deregulated Content---------------------------------------------------------------------Regulated Content

In order to maintain intermediate environments, fans will self-police the community against both rebellious insiders and unwanted outsider influence. Larson and Zubernis expand on this mindset in Chapter 6 of Fandom at The Crossroads: Celebration, Shame and Fan/Producer Relationships: “Both aca-fans and mainstream media have recognized the increasingly reciprocal relationship between fans and producers, facilitated by internet technologies and social media … However, fans do not always welcome the breaking of the First Rule of Fandom [don’t talk about fandom], whether it’s incursion from the creative side or fans themselves doing the rule-breaking.” This agency is why knowledge of fandom networks is so vital if content creators want access to the collaborative value of fandom. If the community feels that their intermediate space is threatened, they will become a rebellious, organized force resistant to commercial exploitation or trans-medial cooperation.

The Intersection of Technology and Intermediary Environments

By acting as an intermediary space digital fandom exists in data limbo, where they “occupy a middle ground, commonly perceived as private and yet in reality public and generally available to anyone with a computer” (Larson and Zubernis). While all fandoms occupy this middle ground, previously established norms in individual fandoms fragment the overarching subculture into varying networks. Generalization of a fandom’s positon in the network can inaccurately represent the range of a fandom’s online presence and attitude toward reciprocal relationships. Understanding the network of semi-private and public spaces enable content creators to respect the online boundaries set by existing fandom norms while being able to engage with the community through acceptable means. Different platforms can provide varying degrees of privacy that fans utilize to maintain a stable status-quo in the networks that fandoms engage in. For example, interacting with content on Facebook ties fandom to the public image of a fan, while a Tumblr blog can provide privacy through a less personal username.

Case Study: The Supernatural Fandom

Figure 3: Infographic displaying details about Supernatural, including imbd episode ratings, average viewership, and number of episodes produced. Source: Author.

The Supernatural fandom and Supernatural content creators (collectively known as the SPNfamily) display how synergy can be found in fan/producer relationships through online networks. This synergy has been successful due to individual efforts made on both sides of the relationship as well as efforts made collaboratively.

Origins of the Supernatural Fandom

The presence of the Supernatural fandom predates the show, with the digital first fan-group being posted on LiveJournal a month before the pilot aired. This is the result of fannish individuals migrating from one fandom to another: “When [X-files] fans migrated to Supernatural, they already understood how to use the Internet to promote their favorite shows, and how to feed their communities so that outside forces like networks and advertisers pay attention. This starts with building a community from the ground up … and directing the energies of that community toward behaviors that are visible to networks” (Reback). This understanding fulfills the first half of a reciprocal relationship: a fandom that is willing to work toward understanding how to help producers create more content.

This devotion has been elevated by the fandom’s use of technology to provide visibility beyond traditional industry measurements. While the fandom can be fragmented across multiple digital platforms, there is an understanding of what platforms are most likely to be seen by outside forces and how to maximize collective value. Due to this, Supernatural fans were among the first to use live-tweeting and strategic hash-tagging to unite their digital network. “Fans believe it’s a way to get across to the network that they are watching and loving the show—something they know Neilsen ratings, which have a relatively small sample size, may not capture.” (Reback).

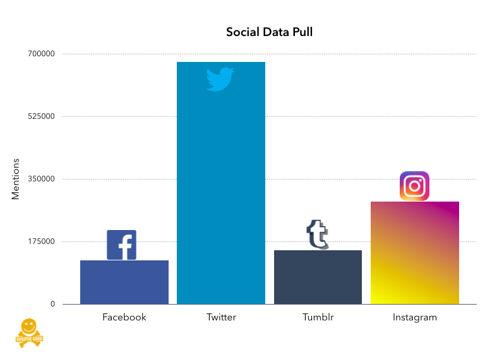

FIgure 4: Measure of posts mentioning Supernatural, categorized by social media platform. Source: Chaotic Good Studios, 2016

Figure 5: Example of the collective power of the Supernatural Fandom using digital visibility during “live-tweeting” events. Source: Chaotic Good Studios, 2016

Reception of the Supernatural fandom by Producers

After collective fan practices saved Supernatural from cancellation, producers were incentivized to reward their fandom through acknowledgment and opening fan/producer dialogue. This was achieved through in-person interactions during fan conventions and through digital platforms. This acknowledgment of and interaction with the fandom cements the other half of the reciprocal relationship between fans and producers. This case study is supported by observations in fan studies, which say that “with face-to-face interaction at conventions, the hierarchical boundaries separating fans and fannish objects begin to break down. Even more strikingly, the advent of Twitter, Facebook, and instant feedback ensures that the relationship between fans and creators is no longer unidirectional. The fourth wall has essentially crumbled, and the reciprocal relationship that Jenkins first hypothesized more than a decade ago in Convergence Culture is a reality” (Larson and Zubernis, Chapter 6).

These interactions first stemmed from producers beginning to use Twitter to further boost engagement during live-tweeting episodes and strategic hash-tagging. This behavior is observed as follows: “Staff can often be found “hosting” a live-tweeting session during the airing of new episodes, offering behind-the-scenes snippets and reactions to the finished product, as well as answering fan questions about plot, or simply conversing. … Supernatural’s production team has developed an air of accessibility. Fans feel comfortable responding to producers, or even attempting to start conversations” (Collier). By participating in content creation outside of the source material and engaging in the established gift-economy, producers were able to immerse themselves into different aspects of the intermediate social spaces that their fandom occupied.

Furthermore, Supernatural began to acknowledge their fanbase through the actual content of the show, establishing a coauthored narrative that validates the fans’ emotional attachment and desire for collaboration with producers. Producers altered aspects of the show to fit fan desires, such as removing Bela, an unpopular character, early into her story arc and extending the status of Castiel, a popular guest star, to a series regular. Through these actions, producers were able to use strategic support of fan activities through transmedia engagement to strengthen the devotion of their fanbase.

Additionally, fan behaviors began to find a place within the canon of the show through episodes catered toward fan activities. A prime example would be the show’s 200th episode, titled Fanfiction. The episode followed a metaplot, where the characters interacted with characters that represented the fandom. It referenced many aspects of the fandom beyond the staff’s interactions with fan spaces, such as discussing the topic of shipping, the unofficial fandom anthem of Kansas’s “Carry on Wayward Son,” terminology used in fan spaces, and the reinforcement of loyalty and family as central themes of the community. These strategies displayed that the producers were aware of fan activities beyond the nodes where producers and fans interacted. This understanding of the overall network allows producers to respect the parameters of intermediate social spaces and only engage audiences where they are accepted. As a result, a precedent is set for the fandom to do the same, respecting the boundaries that producers place on fan/producer engagements.

Coauthored fan/producer relationships

The reciprocal relationship has lent producers credibility in their fandom, allowing for greater access and trust within the fandom network. This acceptance is evident in the mutual use of the “SPNfamily” as an identifier and we/us pronouns being used by both producers and fans. The community has accepted the staff of Supernatural into their subculture, and as a result the producers are able to draw on the power of participation culture and gift economies beyond supporting the show. The staff has been able to engage the fandom to donate to charities, support social causes, participate in civic duties, and enter economic transactions. For example, producers routinely create one-off t-shirt campaigns to promote various causes. The most recent of these events stemmed from a partnership with Hot Topic, a retail store that caters to pop culture. This partnership promoted a new Supernatural t-shirt, where 100% of proceeds would benefit Hurricane Dorian survivors if purchased on September 13th, “Supernatural Day.” This campaign raised $280,000, exceeding expectations of fans and producers, thanks to the collective power of both parties (MacDonald). For more examples of current and past campaigns, explore the Stands website: https://www.shopstands.com/collections/supernatural-tees-apparel-1

This mutual support translates to a broader, digital scale with annual events such as Misha Collins’ “Greatest International Scavenger Hunt” (https://www.gish.com). Collins is a series regular on Supernatural, playing Castiel over the span of 11 years. GISH is an online event fans can pay to participate in, with the dues going toward charitable ventures. Teams of fifteen people compete to win a trip with Collins, and notable entries are recorded in annual coffee table books. Tasks range from activism to acts of abnormality, with raising over $250,000 for survivors of the Rwandan genocide and making two politically opposed politicians wear a “this is our get along t-shirt” both being items on the list. The hunt has broken various world records, including “Largest Media Scavenger Hunt,” with 14,580 participants across 100 countries. For more examples of how this event has harnessed fan power, explore the testimonials of those impacted by these charitable acts: https://www.gish.com/charity-impact/

Figure 6: Examples of collective fan power being used for social good through GISH tasks assigned by Collins. Source: “Charity and Impact,” 2019.

Tools to map Fandom Communities

There are two major tools to consider when approaching online communities as a content creator or manager. Visit Part 1 of this three-part series on Web Scraping and Network Mapping in order to understand the background behind these technologies. These programs can collect data reflecting online fan behavior and help in constructing this data into usable, visual formats. Utilizing these tools allow managers to understand the shape, breadth, and degrees of centrality between different aspects of online fandom spaces.

Web Scraping

Web scraping is a powerful tool when exploring fandoms, as it helps to access information from intermediate spaces that producers may not have access to, while maintaining the semi-private nature of these spaces. As such, web scraping can be used to help remedy the paradoxical relationship between understanding what fans want without being inside the fan community.

The key benefit of web scraping regarding the analysis of online communities is that the technology only collects information relevant to whatever queries that an institution wants to study. This can help combat some of the ambiguous aspects that are reflected in current fan studies and the vague definition of fandom in general.

Once data is collected, institutions are able to alter the format of the data. This is useful in translating the external language of online communities into the internal language that the institution is accustomed to. As such, data can be presented without confusion in a managerial setting. The ability to store and compare data also enables organizations to understand patterns and key traits of their fan communities, leading to more informed and accurate decision-making and trend predictions.

Network Mapping

Because digital fandom communities are diverse and fragmented across various platforms, mapping allows for managers to chart information in a controlled environment. Once an online community is mapped into a network, managers can discover connections or disconnections within said community. This context implies the importance of using multiple different network maps, which falls in line with the importance of different intermediate environments observed in fandom culture. A cross-analysis of networks can help producers see what their fandoms are doing outside of nodes they are connected to, giving them the ability to cater to the specific natures identified in a target group or network segment.

The power of network mapping lays in the ability to look at the larger picture of a network, looking at pieces of a network, and looking at individual nodes to discover patterns or boundaries of data. However, with fan studies, these measures do not account for the size (in number of people) network, but the strength of the network’s shared passion (number of engagements). This may impact the scope of how network maps can be used in understanding fan practices, but enough information can be sought from each map to seek out strategies that promote a reciprocal relationship between a producer and the target audience/fandom.

Once a manager understands the networks of their target communities, they have the opportunity to utilize these networks for spreading information effectively, learning the quickest ways to discover information inside the community, and who key players in the network are. By understanding these traits, managers have more power over the network. They can observe and analyze audiences without gaining acceptance into these digital communities.

Resources

“2019 Best Network Mapping Software.” DNSstuff, August 27, 2019. https://www.dnsstuff.com/network-mapping-software.

Booth, Paul. A Companion to Media Fandom and Fan Studies. Hoboken, NJ, USA: Wiley Blackwell, 2018.

Busse, Kristina. “Geek Hierarchies, Boundary Policing, and the Gendering of the Good Fan.” Framing Fan Fiction, n.d., 177–96. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctt20q22s2.12.

Cavicchi, Daniel. "Fandom Before “Fan”: Shaping the History of Enthusiastic Audiences." Reception: Texts, Readers, Audiences, History 6 (2014): 52-72. https://www.muse.jhu.edu/article/548928.

Christensson, Per. "Scraping Definition." TechTerms. (September 22, 2011). Accessed Dec 13, 2019. https://techterms.com/definition/scraping.

Click, Melissa A. 2013. Spreadable Media: Creating Value and Meaning in a Networked Culture, by Henry Jenkins, Sam Ford, and Joshua Green [book review]. Transformative Works and Cultures, no. 14. https://doi.org/10.3983/twc.2013.0525.

Collier, Cassandra M., "The love that refuses to speak its name: examining queerbaiting and fan-producer interactions in fan cultures." (2015). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 2204. https://doi.org/10.18297/etd/2204

Duffett, Mark. Understanding Fandom: An Introduction to the Study of Media Fan Culture. New York: Bloomsbury Academic, 2015.

Duwhite, Timothy. “Fandoms Rise: Activists and Artists Should Pay Attention to This Pop Culture Force.” Pop Culture Collaborative, March 19, 2019. https://popcollab.org/fandoms-rise/.

Hellekson, Karen. "Making Use Of: The Gift, Commerce, and Fans." Cinema Journal 54, no. 3 (2015): 125-31. www.jstor.org/stable/43653440.

Kiriakou, Olympia. “Big Name Fandom and the (Inevitable) Failure of Disflix.” Transformative Works and Cultures 30 (2019). https://doi.org/10.3983/twc.2019.1598.

Kresnicka, Susan. “Why Understanding Fans Is the New Superpower (Guest Column).” Variety, April 2, 2016. https://variety.com/2016/tv/columns/understanding-fans-superpower-troika-1201743513/.

MacDonald, Lindsay. “Supernatural Stars Raise $280k For Charity with End of the Road Merch: TV Guide.” TVGuide.com. TV Guide, September 28, 2019. https://www.tvguide.com/news/supernatural-stars-raise-280k-for-charity-hot-topic-end-of-the-road-merch/.

“Mapping Communities.” NTEN, July 21, 2015. https://www.nten.org/article/mapping-communities/.

Reback, Dana. “Supernatural Gets It.” Medium. Chaotic Good Studios, December 8, 2016. https://medium.com/chaotic-good-studios/supernatural-gets-it-4b94f0215d18.

Samuel, Alexandria. “3 Questions to Ask About Online Fandom (and Teen Fans).” JSTOR Daily. JSTOR, June 18, 2018. https://daily.jstor.org/3-questions-to-ask-about-online-fandom-and-teen-fans/.

Schulman, Michael. “Superfans: A Love Story.” The New Yorker. The New Yorker, September 13, 2019. https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2019/09/16/superfans-a-love-story.

Stein, Louisa Ellen. Millennial Fandom: Television Audience in the Transmedia Age. Iowa City: University of Iowa Press, 2015.

“Subcultures and Sociology.” Grinnell College. Accessed December 13, 2019. https://haenfler.sites.grinnell.edu/subcultural-theory-and-theorists/fandom-and-participatory-culture/.

Turk, Tisha. “Fan Work: Labor, Worth, and Participation in Fandoms Gift Economy.” Transformative Works and Cultures 15 (2013). https://doi.org/10.3983/twc.2014.0518.

“Welcome to the Greatest International Scavenger Hunt.” GISH. Accessed December 13, 2019. https://www.gish.com/

“What Is Web Scraping and How Does Web Scraping It Work?” Scrapinghub. Accessed December 13, 2019. https://scrapinghub.com/what-is-web-scraping.

Woo, Benjamin. 2014. "A Pragmatics of Things: Materiality and Constraint in Fan Practices." In "Materiality and Object-Oriented Fandom," edited by Bob Rehak, special issue, Transformative Works and Cultures, no. 16. https://doi.org/10.3983/twc.2014.0495.

Zubernis, Lynn S., and Katherine S. Larsen. Fandom at the Crossroads: Celebration, Shame and Fan/Producer Relationships. Newcastle: Cambridge Scholars, 2013.