The arts sector has greatly benefited from the booming crowdfunding industry, as detailed by AMT Lab Contributor Anna Okuda.

The Year That Was

The clock’s ticking is becoming ever more pronounced, 2011 shall soon be placed in the archives of our collective history. So as we bid farewell to this year, let’s not forget the events that made the technology-art axis rotate for a full 365 days!

The year began with the unfolding of the Google Art Project, which revolutionized not only the way we view and how much we could view of an artwork, but also how art in museums became accessible at a global level.

And as art became accessible to a host of people, people became accessible to arts organizations through crowdsourcing. This year, we saw an incredible rise in the use of crowdsourcing, in many different areas and for many different purposes. Operas were crowdsourced, exhibitions were crowdsourced, and even art-works were crowdsourced. But it was the concept of crowdfunding that received a standing ovation from a crowd of people, organizations, and artists.

And in the pockets of these crowds of people were smart-phones and tablets, all glowing with the slide-to-unlock signs. With the rise of the iPhone/Droid/Blackberry and the iPad, many museums developed apps for specific artists or exhibitions in order to augment and guide the viewing experience. In fact, apps revolutionized the way audiences interact with art and museums were quick to capitalize on this opportunity.

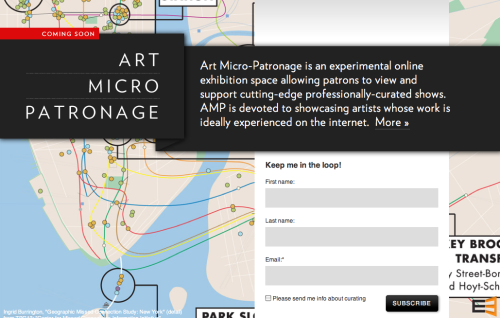

Moreover, some galleries and museums relocated to the online world, and entire exhibitions moved from the realm of the physical to that of the virtual. Paddle8 and Art Micro-Patronage were both introduced this year, and only time will tell whether online exhibition spaces can be just as successful as offline ones. Moreover, there was an increasing emphasis on tailoring the arts towards one’s aesthetic and visual interests through Art.sy and Artfinder, the Pandoras of the art world. Additionally, s[edition] rebelled against the procurement of tangible art forms through its effort to sell digital limited edition prints of big name artists such as Damien Hirst and Tracey Emin.

As always, social media analytics remained at the forefront, and arts organizations realized the importance of sharing and conversing with their audiences through social media platforms such as Twitter, Facebook, and Google+. Many studies were done on Millenials and their motivations, which helped organizations engage and connect with this tech-savvy generation.

And as conversations became heated in social platforms, the world of art and technology did not let us forget that Earth itself is experiencing global warming. There were some excellent fusions of art and technology aimed at the problem of climate change and the move towards green energy by organizations such as GlacierWorks and SolarFlora.

But what will the year 2012 bring in the technology-arts realm? Innovation, progress, the unexpected, awe , wonder, but surely not an apocalypse, right?

Happy New Year!

The Website Exhibition: Old and New

Crowdfunding for the Arts

- Basics: We’ve talked about Kickstarter before and it is one of the most popular crowdfunding tools. Users have two months to raise funds and provide rewards to their patrons. Kickstarter’s guidelines specifically state you cannot use Kickstarter to fund a charity - you can, however, use it to fund projects for a non-profit. For example, No-Space of Brooklyn used Kickstarter to fund the move to and costs associated with their forced relocation.

- Pros: Kickstarter has an “all or nothing” platform, if funds are not raised within the 60 day limit, all pledges are dropped. Kickstarter is well known and a fairly safe bet for those looking to fund their first project.

- Cons: The project-centric ideology limits what can be crowdfunded. Also, Kickstarter uses Amazon Payments. While Kickstarter itself does not require those creating projects to be US citizens, Amazon Payments does, which makes Kickstarter out of the reach of international organizations.

- Fees: Kickstarter charges a 5% fee to successful projects. There is also a 3-5% fee associated with credit card transactions on successful projects.

- Basics: USA Projects is another crowdfunding source we’ve discussed before, and it is a project of USA Artists. Potential projects have three months to raise the funds or receive nothing. The Project sponsors “new creative efforts by accomplished artists across the country” and has raised over $1 million so far. All suggested projects are vetted by artistic experts in the related field.

- Pros: USA Projects has a strong institutional background with USA Artists, allowing it to have a gift-matching component, and the average donor gives more than Kickstarter users. All donations are tax-deductible, and artists offer perks for donating.

- Cons: USA Projects only accepts artist members who have previously received a grant or award from their partner and recognized organizations as an individual artist.

- Fees: 19% of all donations go to USA Projects “for use in furthering its general charitable and educational purposes.”

- Basics: IndieGoGo touts itself as “the world’s leading international funding platform”, and is open to “anybody with a great idea”. Projects are not curated. Users have up to 120 days to reach their goal, but unrealized goals still receive the pledged funds.

- Pros: Donations to non-profit organizations on IndieGoGo are tax-deductible, different donor levels have perks related to the campaign. Analytics tools allow campaign managers to track where/who funds are coming from, as well as capture contact information from funders. Anyone can use IndieGoGo for anything, which is has unlimited possibilities. IndieGoGo also has partnerships with non-profit organizations that fiscally sponsor projects.

- Cons: No vetting process on campaigns means your next big, great idea may not carry as much weight for donors as a website where projects are curated. Also the website caters more to individual artists’ projects than arts organizations - arts campaigns are not listed under “Causes” unless they have an educational component.

- Fees: IndieGoGo takes 4% of the money your project manages to raise, if your goal is met. Should your project fall short, IndieGoGo takes a 9% cut of funds raised. International campaigns may have higher fees.

- Basics: RocketHub is a crowdfunding platform for anyone who would like their creative work to be funded, developed or distributed. RocketHub has two levels of fundraising, one is a crowdfunding tool open to anyone. Campaigns have between 15 and 90 days to be funded, unrealized goals will still be funded, but met goals have rewards within RocketHub. The second is called a “LaunchPad Opportunity”, which is a reoccuring vetted submission process. Projects chosen receive an opportunity that will advance their business or campaign beyond simple fundraising (for example, the winner of the LaunchPad Opportunity will work with an expert publicist on generating buzz for their project). A team of judges at RocketHub examines all submissions, and Facebook users vote to help decide which projects to put on the website to fund.

- Pros: Successfully funded campaigns on RocketHub allow the campaign creator to submit 5 entries to their LaunchPad Opportunities without a cost. RocketHub has partnerships with non-profit organizations that fiscally sponsor projects.

- Cons: RocketHub does not have a specific “Art” category, although individual projects could fit well into their other categories.

- Fees: For crowdfunded fees, RocketHub charges 4% of the money you raise if your goal is met. For unfunded projects, the fee is 8%. RocketHub also charges a 4% transaction fees for credit card charges. For first time submitters to a “LaunchPad Opportunity”, there is a submission fee of $8. Those who have a project successfully crowdfunded do not have this fee.

IndieGoGo and RocketHub work outside the states, but there are other crowdfunding tools internationally. There are also tools like Philanthroper, which is a daily deal crowdfunding site for non-profit organizations. There are resources for staying on top of crowdsourcing trends, too. Ultimately, an individual or organization has to consider what type of crowdfunding campaign will work for their needs before deciding on one. If there are any other crowdfunding topics or questions you’d like answered, leave a comment, and we’ll see how we can help.

Peer to Peer Fundraising in the Digital Age

Back in the day, peer-to-peer fundraising was done with phone calls, letter-writing campaigns, and in-person visits. Now we have a whole new universe of not only digital communication, but digital relationships. Recently, I came across a cool infographic from Blackbaud that illustrated the power of harnessing online social networks to raise money for charity. It got me thinking- what are organizations doing to take advantage of this?

Peer to Peer Products

Peer to peer fundraising tools offered by Blackbaud (Friends Asking Friends) and Convio (Team Raiser) enable team members and participants to set personal fundraising goals and then go about asking friends and family for donations, the deadline for raising funds usually being an organizational event (primarily races to cure diseases). In fact, according to the Chronicle of Philanthropy, all of the top five P2P Giving organizations in 2010 were health organizations (for the top 25 online giving orgs of 2010 view slide 8 here).

- Convio's Team Raiser

- BlackBaud's Friends Asking Friends- thanks Frank Barry!

If you put on these participant-heavy events, here’s a post about 3 ways to add new event participants. But according to a webinar by Blackbaud on Tuesday, you don’t have to have an event in order to use these tools. Organizations are using them both with ongoing fundraising and with virtual or digital events as well.

Website Tools

Both the Salvation Army and the World Wildlife Federation have cool things that are like the peer to peer tools above, but are designed for ongoing fundraising. The Salvation Army has an “Online Red Kettle”. You can either start your own red kettle, donate to an existing one, or send an eCard to your friends (via email) urging them to support one. If you set up your own, you can have your own fundraising meter, banner ad, or Facebook app.

- Online Red Kettle

On the WWF’s site, you can search for or make a super-cute Panda Page (it can be for any animal), then email it to your friends and family. As of right now there weren’t any social media plug-ins on the page.

- World Wildlife Federation Panda Page

Another way to configure your website to encourage peer-to-peer fundraising (also suggested by Frank Barry and Steve MacLaughlin of Blackbaud) is to immediately prompt online donors to share with their social networks when they make a gift, instead of only receiving a regular confirmation page or email. Use Facebook and Twitter plug-ins (like and share buttons, retweets etc) to make it simple for them to share with their networks.

You can also embed those same plug-ins in different areas of your website. Enable somebody to “like” a concert, or retweet a story about your outreach program.

Facebook Causes

Causes has alternately been held up as a model for success and derided for not delivering on its promises. The basic idea is that it allows anyone to create an advocacy group, or “cause”. This cause can then raise funds to donate to a charity. One of the most successful causes is The Nature Conservancy, which has raised over $400,000. An arts success story is Keep the Arts in Public Schools, created by Americans for the Arts, which has raised almost $50,000. People can become members of the cause, donate, tell friends, and “give a minute” by watching and participating in ads that earn money for the cause.

Aaron Hurst of Taproot has been a critic of Facebook Causes since his organization devoted $3,000 of staff time to creating their Cause shortly after Facebook launched the feature. They have received only $60 in return to date. Is Causes a rip-off or a revolution in fundraising? The jury’s still out, but it’s my guess that the different results are due to a combination of knowing how to facilitate peer-to-peer fundraising well, an organization’s existing fan base, and the type of cause. It’s interesting to note that at the Nature Conservancy, social networking was never primarily about raising money- it was “first and foremost a tool for brand and reputation,” said an organizational representative in this 2009 Washington Post article.

Kickstarter

Much has been written about Kickstarter and its cousins, IndieGoGo and RocketHub (among others- check out Pat’s article from last year). And certainly anyone using these tools knows that it’s all about mobilizing your social network. It’s really better suited to specific projects than ongoing fundraising, however. And unless you are able to get your supporters to in turn appeal to their own friends, you are probably going to be asking the same people you always ask anyway.

According to a recent article from NPR, Kickstarter has raised over $50M for creative projects since launching in 2009 and currently attracts $2M in pledges each week for projects.

Check out this Mashable article on other social fundraising alternatives.

The philosophical side

There’s a lot more to this than just raising more money. It’s also about building donors of the future, and increasing not just donations but engagement that will later lead to donations.

On Wednesday, the Case Foundation hosted the Millennial Donors Summit to talk about millennials’ approach to charitable giving. A lot of the points that were made apply not only to millennials, but also to peer-to-peer and social media fundraising. The following is excerpted from Katya’s Non-Profit Marketing Blog:

- It’s not about telling millennials to support you; it’s about creating a vested interest in what you are doing with joint ownership. Let millennials manage your community, design your logo or otherwise be an active partner in what you seek to accomplish.

- At some point, you have to build an army. You can only sell something yourself so many times—you need your community doing it for you, performing the heavy lifting. So give them ownership.

- To be trusted on the web, be an individual, not an organization.

- Look for the small yes.

Something that Frank and Steve mentioned in their webinar this week is that it’s more important to tell a compelling story than it is to make the ask when using social media to fundraise. They gave examples of YouTube videos where the ask was a subtitle. The story is what gets people interested.

Also, give them something to do besides donate. Encourage them to like your page, share the link or video, comment, or even answer a question (like at Free Rice) or send mom a card.

Many of these examples are from very large organizations that have teams of people to create these web tools. But these ideas can be applied on a smaller scale. How have you empowered your constituents to raise money and awareness for you? Do you know of arts organizations who are doing it successfully?

Philanthroper: A New Daily Deal Site for Non-Profit Donations

A new daily deal site launched this past month, but this site doesn’t offer a deal for a spa trip or half off dinner at some posh restaurant. New site Philanthroper offers a non-profit story a day, a daily solicitation for a non-profit doing some good, and asks visitors to give just one dollar. Launched by Mark Wilson, reporter for Gizmodo and Esquire, Philanthroper aims to make donating a daily habit for the internet culture.

The idea behind Philanthroper is very similar to dynamite daily deal sites like Groupon and Living Social. Each non-profit gets front-page realty on the site, but just for 24 hours. Instead of a daily discount, Philanthroper shares the stories of non-profits, from local to global, and gives visitors the opportunity to donate a dollar. When the 24 hours come to an end, a new non-profit goes up and the previous day’s organization receives their funds within about a week.

A new daily deal site launched this past month, but this site doesn’t offer a deal for a spa trip or half off dinner at some posh restaurant. New site Philanthroper offers a non-profit story a day, a daily solicitation for a non-profit doing some good, and asks visitors to give just one dollar. Launched by Mark Wilson, reporter for Gizmodo and Esquire, Philanthroper aims to make donating a daily habit for the internet culture.

The idea behind Philanthroper is very similar to dynamite daily deal sites like Groupon and Living Social. Each non-profit gets front-page realty on the site, but just for 24 hours. Instead of a daily discount, Philanthroper shares the stories of non-profits, from local to global, and gives visitors the opportunity to donate a dollar. When the 24 hours come to an end, a new non-profit goes up and the previous day’s organization receives their funds within about a week.

Why just a dollar? As the site states:

So you can donate another $1 tomorrow. And another the next day. Use Philanthroper daily, and we guarantee, you'll donate more over time than you would have otherwise plus it won't sting your bank account so badly. Use Philanthroper every day and you'll be on the right track to give more, more easily. If you're compelled to make a larger donation, fantastic. We always link their site. So go for it.

Philanthroper restricts the amount you can donate to just that one dollar and limits visitors from donating more than once a day. The idea here isn’t to solicit a major gift, but to create a culture of daily giving. Donating a single dollar can be a pretty tempting request. Personally, I spend more on a cup of coffee or downloading an app that will make my phone sound like an air raid siren.

The financial cut Philanthroper takes from each donation is the biggest thing setting them apart from other crowdfunding sites like Kickstarter and USA Projects. That’s because the amount Philanthroper retains is zero – you read that right, zero. Philanthroper states right out that they will never take a cut of your donation, although the site’s payment service mPayy will take a whopping 1% of each donation – a penny.

This is how Philanthroper can offer that minimum donation level of $1, whereas other non-profits are often forced to ask for a minimum of around $10 due to the processing rates of current payment services. Support for the site comes from advertising, so as website Arstechnica puts it “…only your eyeballs, and not your charitable gifts, are paying to keep things going.”

How does a non-profit get a daily deal? The site selects only official 501(c)3 organizations, with a special interest in those that bring in less than $1 million per year. The main focus is on those non-profits that are young and growing and could use every single extra dollar. Religious non-profits are not promoted on the site and individuals raising funds will not make the cut. Think you know a non-profit that’s perfect for the site? Philanthroper invites site visitors to suggest tips for non-profits out there worthy of their own daily deal.

Creating a habit of daily giving in our current internet culture is a pretty exciting idea. Philanthroper is taking advantage of the impulsive nature of users of sites like Groupon and Living Social. If the popularity of the site can continue to grow, there is a possibility to make a huge difference for many small non-profits. Visit the main site here and check out what today’s daily cause is that you can throw a dollar towards.

USA Projects: A New Crowdfunding Platform for the Arts

Created in 2005 as a grant-making and arts advocacy group based, United States Artists (USA) acts as an avenue for individual artists to find private funding for themselves and their projects. Earlier this month, they entered into the foray of crowdfunding platforms with the launch of the USA Projects, a fund-raising engine that is specifically focused on funding individual artists and their projects through grassroots micro-donations.

Created in 2005 as a grant-making and arts advocacy group based, United States Artists (USA) acts as an avenue for individual artists to find private funding for themselves and their projects. Earlier this month, they entered into the foray of crowdfunding platforms with the launch of the USA Projects, a fund-raising engine that is specifically focused on funding individual artists and their projects through grassroots micro-donations.

Part social network, part fund-raising vehicle, the USA Projects site combines many aspects of other popular crowdfunding sites like Kickstarter, RocketHub, and IndieGoGo. While still in beta testing, the site has already garnered some major attention according to The New York Times:

In testing, the Web site attracted roughly 36,000 unique visitors and raised a total of $210,000, with an average of $120 from each of 1,500 small donors, Ms. DeShaw said.

Not bad at all for a recently launched crowdfunding platform for the arts. Still, there are some major differences between USA projects and the other crowdfunding sites out there. Here’s a look at some of the similarities and differences between USA Projects and its peers:

Similarities

- It’s all or nothing, baby – Like Kickstarter and Rockethub, USA Projects adheres to the “all or nothing policy” wherein projects must meet 100% of their stated fundraising goal, or the funds are returned to their respected donors. Some people have seen this as a great motivator for their projects, while others claim it is a waste of time. This isn’t true of every platform though, IndieGoGo allows people to keep all funds contributed to their projects, even if the final fund-raising goal has not been met.

- The final countdown – As is common on crowdfunding sites, artists on USA Projects have three months in which to raise the money for their projects.

- Getting friendly – Most of the platforms out there have a social media element to them, and the USA Projects site is no exception. Users on the site can create profiles, follow artists and funders, send messages, leave comments, and view recent activity on the projects they have funded or have an interest in. This creates a more personalized experience as well as a stronger connection to the projects and the artists.

- Incentivizin’ – Crowdfunding sites mirror traditional donor campaigns in that different donation levels come with various perks and rewards. Since the perks and rewards are determined by the artists, the endless possibilities are limited only by the artists’ capacity to deliver. Rewards might range from a personal note from the artist to prints or video downloads of the resulting artwork, from private studio visits to the chance to sing back-up on the artist’s CD, etc.

Differences

- At what cost? - In order to meet the bottom line, sites like Kickstarter and RocketHub will charge a percentage of the final funds and for the credit card processing fees. These fees can amount from 5-8% of a project’s total funds raised. Since United States Artists is a not-for-profit organization, there is no fee attached to the projects.

[Correction: According to an FAQ on the USA Projects Web site: "81% of every dollar pledged goes directly to the artist’s project, and 19% supports USA’s programs for artists and the site’s administration." So with this information, it appears that the percentage of funds received by US Artists is two or three times the percentage received by other crowdfunding sites. -- Hat tip to Justin Kazmark.]

- Who gets to play in the sandbox? – Now we hit the major difference between USA crowdfunding and the other platforms out there: not just any artist can add a project to the site. In order to appear on USA Projects, the artist in charge must have received a previous grant or award from a USA Project Partner or recognized organization. Visit the main website here to view all of the recognized organizations and their award/grant programs.

This requirement for artists to have been granted a USA grant, or equivalent from a partner organization, in the past in order to pilot a project raises some interesting questions about this model of crowdfunding:

- Is the policy too exclusive? Requiring grants or awards in order to even start a project excludes a large number of artists right off the bat. And while there are a considerable number of organizations partnering with USA, they do not cover the full spectrum of creative professionals in the United States.

- Does the grant/award requirement go against the spirit of crowdfunding? One of the exciting aspects of crowdfunding is that virtually anyone can start a project and find the funders to make it happen. So what happens to all the first timers? The energetic artists with a great idea and the will to make it happen, but lacking the professional background to make it onto the site? It can be argued that much of the success individuals have had on sites like Kickstarter can be attributed to the strength of the idea behind the project, not necessarily their past accomplishments.

- Will having “approved” artists act as an incentive for people to donate larger amounts? There is definitely a reassurance when donating to an artist who has had some previous success and support. But most existing crowdfunding platforms already have the reassurance of returned funds and set time limits, so how big of an impact will having pre-approved artists make? Will USA’s stamp of approval result in more donations or larger donations for these artists?

It will definitely be interesting to see how the USA Projects platform grows over time and if the requirements for projects will stay the same or evolve with that growth. Additionally, how might this model for crowdfunding the arts affect other existing platforms?

Four Quick Tips for Launching a Crowdfunding Project

Broadway producer, Ken Davenport, recently surprised the theatre world with his decision to launch a crowdfunding campaign to produce a revival of the musical Godspell. The ambitious project is hailed as the "first-ever community-produced Broadway musical" and will probably not be the last of its kind. Crowdfunding, it seems, is here to stay. Crowdfunding is essentially the pooling together of financial resources via the internet. Typically, the project manager solicits financial donations from the public via a web-based platform. Crowdfunding can be used to fund just about any type of project, whether its reviving a Broadway musical or financing a band’s studio time. While the idea of pooling together financial resources from the larger community to fund an artistic project is certainly not a new model, the internet is putting a new twist on things.

Here are 4 quick tips to consider before you or your organization embark on a crowdfunding campaign:

- Choose an Appropriate Platform: There are many platforms to choose from for your crowdfunding campaign. Kickstarter and IndieGoGo are two of the more popular platforms. However, it's not always necessary to sign up with a third party. It is possible to launch a campaign through your own website, but strict securities and exchange commission regulations may make this option trickier. It's important to gauge the specific needs of your project and organization prior to choosing a platform.

- Be Aware of All-Or-Nothing Policies: If you decide that a platform like Kickstarter or IndieGoGo is the best way to go, then take the time to become familiar with their policies. Platforms like Kickstarter and Rockethub have an "all or nothing" policy that requires a project to meet ALL of its stated fundraising goals in order to receive any funds. If a project falls short, then no money will be collected. Other platforms like IndieGoGo allow you to keep the funds you raise, even if you do not meet your fundraising goal. Some artists and groups find Kickstarter’s “all or nothing” structure to be a great motivator. Others consider it a potential waste of time if their goal is not met.

- Consider the Legal Ramifications: While services like Kickstarter and Indie GoGo make it virtually painless to launch a campaign, it's always a good idea to make sure your legal ducks are in a row. Depending upon the complexity of the offer, you may need to meet particular requirements. Since the donors are considered investors in the Godspell production, Davenport's offer had to be reviewed by the Securities and Exchange Commission before it could be presented to the public.

- Read the Fine Print! Some platforms do have fees and other hidden costs associated with their services. Take the time to understand the economic model that the service is operating on -- fee structure, donation collection process, funds disbursement, etc.

Raising More Money for the Good Work We Do

This afternoon, I had the pleasure of working with Jerry Yoshitomi on a conference session dedicated to grassroots fundraising for the attendees of The Association of American Cultures (TAAC) conference in Chicago. Below are the slides for each of our presentations. Jerry's presentation on grassroots fundraising:

My presentation on online tools and practices for grassroots fundraising:

Kickstarter: funding for (and by) the masses

Crowdfunding websites are a simple way for artists to solicit and accept donations online. One of the best-known sites is Kickstarter, which hosted the record-breaking crowdfunding of Diaspora. With Kickstarter, you set a fundraising goal and have three months to achieve it. If you reach your goal within three months, you keep the cash. If you don’t, the funds are returned to your backers. You design a menu of rewards to motivate backers to give. And, you keep 100% of ownership over your project -- an important consideration for artists dealing with copyright and distribution issues.

Helen DeMichiel, who funded a series of webisodes with Kickstarter, says the all-or-nothing structure is a great motivator. “You have to hustle,” she explains, and your backers get caught up in the excitement.

A previous project backer and current project starter, Tirzah DeCaria points out that most projects are funded largely by backers within the artist's existing network. She advises artists to look at Kickstarter as an opportunity to consolidate and mobilize your network rather than as a tool for reaching large groups of new fans. Of course, Kickstarter isn’t for everyone. The site is curated, and in addition to an application process, projects must have a U.S. address and a U.S. bank account. And there are the guidelines.

In a quick scroll through Kickstarter’s current projects, I came across many projects posted by individual artists or small groups, as well as projects by a design studio, a non-profit performance company, and a video game developer. Kickstarter clearly doesn't exclude businesses, but established organizations aren't the primary users. If your organization is considering a project, Joe's post on micro-donations has some good thoughts and advice. And, again, consult Kickstarter's guidelines.

Other crowdfunding sites for artists:

- Projects on IndieGoGo can be based anywhere in the world. Unlike Kickstarter, the site isn’t curated, so projects cover a broad spectrum -- creative endeavors, causes, and entrepreneurial work. And, IndieGoGo is not an “all-or-nothing” enterprise. You can keep any funds you raise along the way. IndieGoGo also has several innovative partnerships, including a fiscal sponsorship program through Fractured Atlas and the San Francisco Film Society.

- RocketHub is another “all-or-nothing” crowdfunding site geared toward artistic and creative projects. RocketHub is not curated, though projects must be legal and “in good taste.” You must have a PayPal account to start a project.

What is your experience with crowdfunding art? Should established organizations stay out of it or join in the fun?