introduction

Investment in cultural facilities can be transformational within communities, and not just through the services they provide, the jobs they create, or the money channeled into the local economy. Cultural facilities can have tangible impacts on a community’s built environment and energy systems. The arts and cultural sector is experiencing a significant increase in sustainability work, with a number of organizations beginning to measure and report impact, incorporate sustainability into values, or work toward positive climate goals (Environment and Energy Leader 2024). This work often centers around facilities’ improvements with obvious impacts at an organizational level, typically reducing emissions, lowering energy bills, and improving aesthetics. However, this investment in facilities also likely contributes to sustainable development at a community level and beyond.

To evaluate this complex relationship, it is useful to use a case study. This article focuses on the city of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania - specifically, the Oakland neighborhood. A few factors contribute to its relevance in this discussion, particularly the city’s deep-rooted relationship to the extraction economy, concentrated philanthropic investment in culture and education (Financial Post Magazine 1990), a culture of innovation, and early environmental response (Tarr 2003 ). In each of these interrelated aspects, Pittsburgh has served as a model for cities across the world, which demonstrates potential for the city to be a leader in environmental innovation in arts and culture.

This article explores the impact of historical and ongoing arts and cultural development on key sustainability factors in Pittsburgh’s Oakland neighborhood. Key cultural assets include the Carnegie Museums of Art and Natural History (formerly the Carnegie Institute), the Carnegie Library and Music Hall and Phipps Conservatory and Botanical Gardens. Phipps Conservatory and the Carnegie Museums were constructed in the 1890s, supported by Gilded Age industrialists. This investment has proven to be unequivocally influential in the neighborhood, in tandem with its educational assets University of Pittsburgh and Carnegie Mellon University (formerly Carnegie Tech and Mellon College). Over the last century, continued investment has been made in these cultural facilities and related infrastructure to meet contemporary needs, and each institution has incorporated sustainability initiatives in different ways.

What does it mean to have an environmental impact?

Sustainable urbanism is defined as “walkable and transit-served urbanism integrated with high performance buildings and high performance infrastructure” (Farr 2007). Demonstrating sustainability at a community level, this involves a series of complex systems, often interacting and overlapping. There are a number of thresholds for evaluating a sustainable community, including economic activity, density, transit, land use, biodiversity, public health, access to housing and amenities, energy usage, water treatment, and food systems, among others. To gain a comprehensive understanding of organizational impact, a variety of these factors will be considered for the purposes of this article.

Pittsburgh: The Rise and Fall of Industrial Economy

In the rise of the industrial revolution, Pittsburgh’s natural environment attracted ambitious investors to the city. With split rivers convening at the Ohio River and connecting ultimately to the Mississippi River, Pittsburgh was tied to the global marketplace. Natural resources, such as coal, iron, natural gas, and limestone, were readily available making the city a logical choice for steel production and other growth industries (Visit Pittsburgh).

As industrialists reached unprecedented wealth, many chose to invest back into the city - and particularly in educational and cultural institutions. Pittsburgh grew in wealth through the world wars, and then suffered significantly in the industrial collapse of the 1970s. As industry left, necessity paired with available cultural resources to supported the innovative, if not gritty, spirit which pushed the city through its well-documented re-birth in the 1990s.

The industrial economy also created serious environmental and air pollution concerns. By the 1940s, residents started to call attention to the undeniable health issues plaguing the city, and Richard Mellon spearheaded the “Allegheny Conference on Community Development” to shape the city’s new look. In 1941, this committee successfully led one of the city’s first air quality campaigns pushing for regulation on fuel burning (Tarr 2003). In the 1960s, Pittsburgh’s Rachel Carson wrote Silent Spring , which launched environmental concern to a national scale and contributed to the designation of Earth Day. Though air quality concern hasn’t gone away, has improved dramatically since this time.

Now Pittsburgh is one of the most “livable” cities, with a low cost of living and robust arts and cultural ecosystem supporting a high quality of life. With seven local universities including a medical school and Carnegie Mellon University’s ties to robotics and tech, Pittsburgh is now well-known for being a town of “eds and meds.” Considering this context, Pittsburgh can be a meaningful case study in evaluating how arts and cultural institutions, many established in the industrial era, contribute to sustainable community development. Breaking this down even further, there are 90 neighborhoods in Pittsburgh, divided into 16 planning sectors. Planning sector 14 consists of North, West, Central, and South Oakland neighborhoods - or commonly referred to collectively as “Oakland.” This sector demonstrates a particularly interesting influence between the institutional development as an influence on Oakland is an example of the influence of institutions.

Oakland: A Cultural Epicenter

Pittsburgh’s Oakland neighborhood is the third largest cultural district in Pennsylvania after Downtown Philadelphia and Downtown Pittsburgh. Today, the neighborhood is home to the Carnegie Museums, Phipps Conservatory and Botanical Gardens, Carnegie Mellon University, the University of Pittsburgh, and a number of other significant institutions as noted earlier.

In the late 1800s, Oakland was considered a “non-industrial zone.” With abundant green space, the area was named after William Eichbaum, one of the early settlers in the space, whose land had many oak trees (“Oakland: A Look Back Over the 20th Century”). By the 1840s, Oakland’s population started to grow, and by 1860 it was annexed into the city. By this time, Oakland was already a fairly affluent neighborhood where industrialists resided far from the plants in Homewood, Braddock, and down the Monongahela River.

Oakland Neighborhood in 1910

Image Source: Brookline Connection

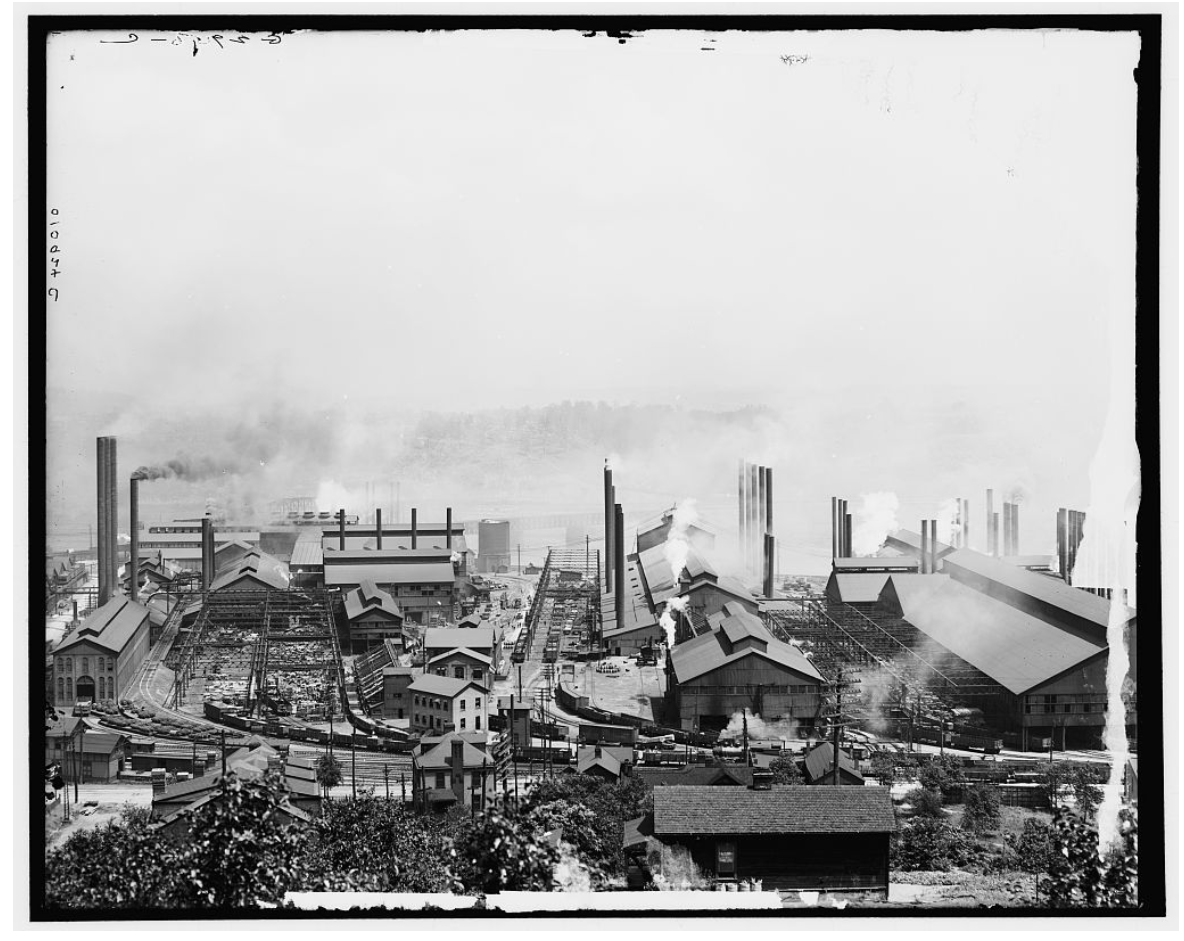

Carnegie Steel Works, 1907, Homestead, PA

Image Source: Library of Congress

Oakland has been shaped as a direct result of concentrated philanthropic investment from Andrew Carnegie and his contemporaries during a period of heavy extractive economies that left a distinct and extensive ecological damage in the region. In the late 1800s, while industry continued to rise, a philanthropic approach rose, in part due to Carnegie’s Gospel of Wealth, which prioritized the establishment of longstanding facilities which would support the “greater good.” At the time, these facilities were state of the art, calling on some of the finest architects in the United States.

Carnegie Museums

In 1890, Andrew Carnegie stood on Herron Hill alongside the mayor and head of the Library Building Committee and selected the site for the future Carnegie Institute. Carnegie had a vision for an institute that would incorporate a library, gallery space, natural history hall, and a music hall (Gangewere 2011). As early as 1881, Carnegie offered to $1 million dollar gift to the City to develop this space, though the vision did not materialize until 1895 (Carnegie Library).

1890 Map shows sketch of the future site of the Carnegie Institute.

Image Source: Pittsburgh Historic Maps - ArcGIS

97 architects placed their bids to bring Carnegie’s vision to life, but Longfellow, Alden, and Harlow ultimately earned the role, designing the Italian Renaissance structure Carnegie would later refer to as his “monument” (Gangwere 2011, “Our History”). In 1985, Smithsonian Architecture Historian said, “the building itself is the greatest object of the entire museum collection” (“A Journey to France”).

Carnegie Institute in 1895

Image Source: Carnegie Museums

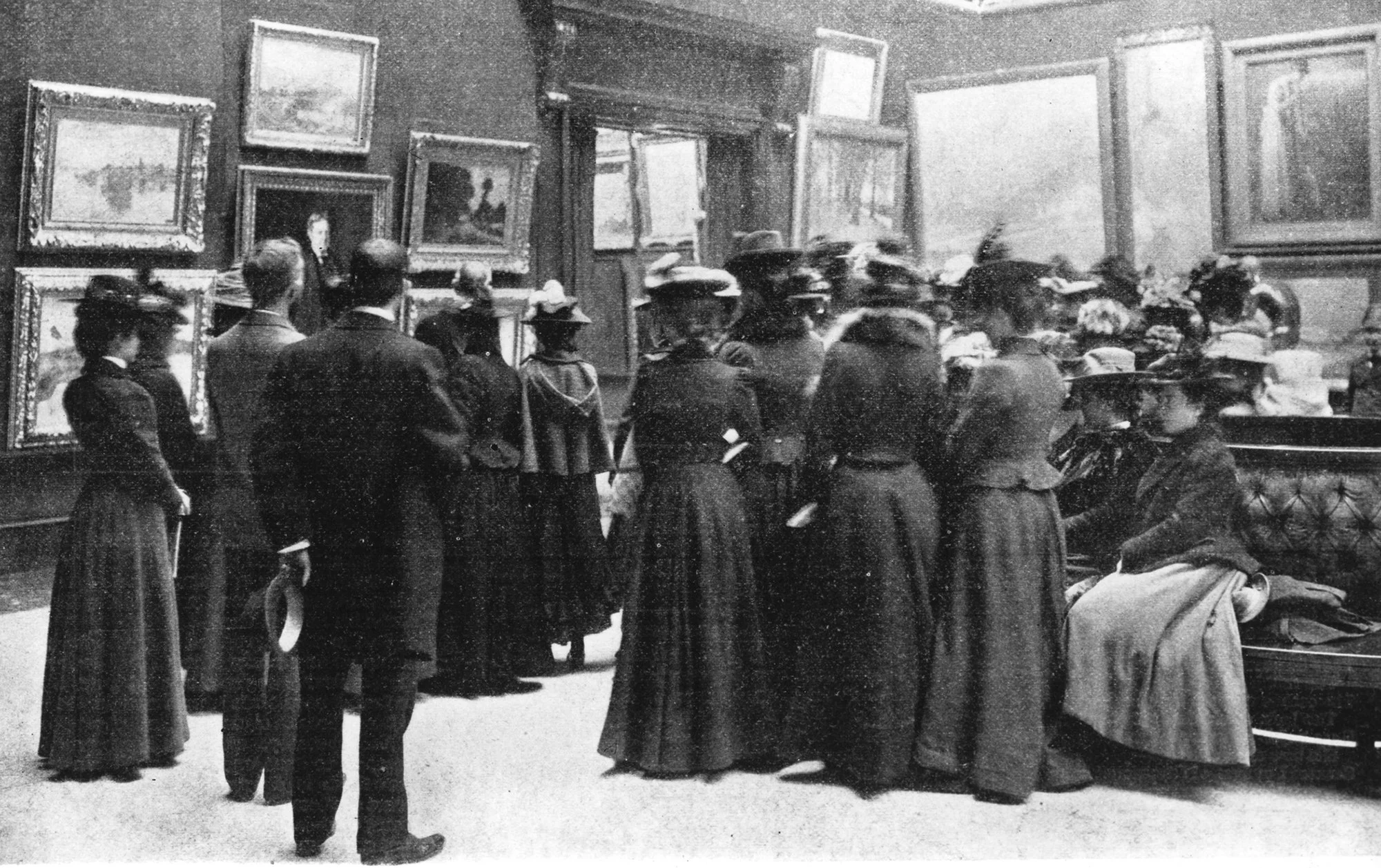

The facility became an anchor for the cultural development of Oakland, as Carnegie sought to make Pittsburgh “as famous for art as it is now for steel” (Wayne 2024). In 1896, the institute hosted the first international contemporary art festival, the Carnegie International. This set the groundwork for developing a more permanent institution, which would serve the community in perpetuity as one of the first contemporary art museums in the world. It was reported that people of all classes gathered to see the festivals artwork, however, there were notable differences in opportunities.

Attendees at the first Carnegie International in 1896.

Image Source: Carnegie Museums of Pittsburgh

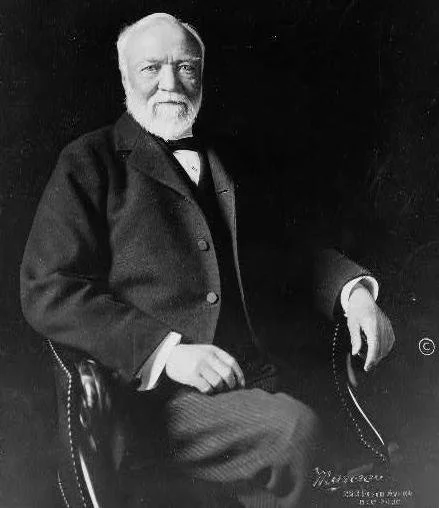

In the Gospel of Wealth, Carnegie’s famous essay outlining his philosophy of philanthropy, he praised the power of institutions (1889). Particularly, supporting the value of investing in educational and cultural facilities that would uplift the working people. “It is well, nay, essential for the progress of the race, that the houses of some should be homes for all that is highest and best in literature and the arts, and for all the refinements of civilization, rather than that none should be so.” Over the course of his lifetime, he supported development across the world, though remained committed to uplifting his ‘home city’ of Pittsburgh through Carnegie Tech (1900), Carnegie Museums (1895), Carnegie Music Hall (1895), the Central Library (1895), and a number of other libraries around the region.

Andrew Carnegie sought to bring “Sweetness and Light” to the people of Pittsburgh through his philanthropy.

Image Source: Library of Congress

At the presentation of the Carnegie Institute in 1985, Carnegie stated that his philanthropy sought to “bring into the lives of the toilers of Pittsburgh sweetness and light” (Carnegie, 1895).

In many ways, the Oakland museums accomplished Carnegie’s goal, providing opportunities previously inconceivable to Pittsburgh residents. For example, the Hall of Architecture brought plaster castings of the world's most famous architectural pieces at a time when Pittsburgh residents would likely never have the chance to see these wonders on their own (“Our History”). Additionally, at the Natural History museum, an 1898 dinosaur expedition funded by Carnegie brought Pittsburgh one of world's most famous fossils, Diplodocus carnegii, which has been replicated and displayed around the world.

By 1904, the museums had begun their first expansion, adding dedicated space for the art galleries and natural history museum. This change significantly increased the size of the facility, and removed the original Venetian towers Carnegie felt looked like “donkey ears” (Gangwere 2011).

Many additional expansions and enhancements were made over the course of the century. In 1974, the Scaife Galleries were constructed on the northern side of the Carnegie Museums campus, named in honor of Sarah Scaife, a prominent philanthropist and the niece of Andrew Mellon. This space is a significant portion of the Carnegie Museum of Art’s current footprint. Between 1980 and 1993, the Carnegie Museum of Natural History developed the Hillman Hall of Minerals & Gems, Polar World, the Benedum Hall of Geology, the Walton Hall of Ancient Egypt, and the Hall of African Wildlife.

Bellefield Boiler Plant - “The Cloud Factory”

Expansion of the institute came with a growing demand for energy. In 1907, the Bellefield Boiler Plant was constructed south of the Carnegie Museums’ campus to provide steam power for the facility. At the time, it was one of the largest institutional power plants ever constructed (Susany 1967). Today, the plant services a significant tract of Oakland, including neighboring Carnegie Mellon University, Phipps Conservatory and Botanical Gardens, and portions of the University of Pittsburgh. The boiler is now owned by a consortium of these Oakland institutions and managed by the Carnegie Museums (A. Young, personal communication, May 6, 2024). Throughout its history, the boiler has been powered by both bituminous coal and natural gas. Bituminous coal was abundant in the Pittsburgh region, first found at Mount Washington, just across from the Monongahela River (Department of Environmental Protection). This coal type has a wide range of uses, and is often referred to as “steam coal.” However, it is also associated with high levels of sulfur, nitrogen and other pollutants.

In fact, the Bellefield Boiler had a reputation for violating air quality standards. The facility earned the moniker “the Cloud Factory,” from author Michael Chabon in his 1988 novel The Mysteries of PIttsburgh, referring to exhaust puffing from boiler’s stacks throughout the winter (University Wire 2020). In 2006, owners were fined $175,000 for exceeding limits for sulfur dioxide and other particulate emissions. In 2008, the boiler was cited by the Health Department for excessive viable emissions, and fined $9,175.

By 2009, the facility completely transitioned to natural gas, a fuel source which burns more cleanly at the point of combustion. This switch was estimated to correspond with a 99% reduction in sulfur dioxide emissions and a 76% reduction in particulate emissions - totaling an estimated annual reduction of 870 tons of emissions (US Fed News Service, Including US State News.).

CO2 Emissions from Bellefield Boiler Trend Downward Following Transition to Natural Gas

Image Source: GHG Facility Details, Environmental Protection Agency

However, natural gas is primarily methane which carries its own risks. Methane is an extremely potent greenhouse gas with approximately 27-30 times the warming potential of carbon dioxide. While the coal to natural gas fuel transition reduces local pollution and air quality threat, methane may leak into the atmosphere from natural gas wells, storage tanks, or processing plants with significant health and environmental impacts (U.S. Energy Information Administration).

The Bellefield Boiler Plant provides steam energy for the Carnegie Museums, Phipps Consevatory and Botanical Gardens, and a number of other Oakland Institutions.

Image Source: The Zach Morris Experience

Overall, district energy systems, like the Bellefield Boiler, serve to make energy more reliable and cost effective for the neighborhood. At a typical power plant, only about a third of fuel energy is transferred to end users, while the remainder is released into the atmosphere or surrounding waterways as heat energy. Conversely, district energy systems placed in higher density areas capture most heat energy through combined heat and power systems, which produce steam or chilled water.

Demand for the system exceeded its limits in 2009, and the University of Pittsburgh opened the Carillo Steam Plant on the north side of campus, also powered by natural gas (Barlow 2009). While the power system for the community continued to grow and adapt, it was simultaneously serving a much larger ecosystem overall, with substantial growth on all arts and education campuses throughout the late 20th and early 21st centuries. Simultaneously, attention to the environmental impact of individuals and organizations continued to develop. The Oakland neighborhood and its cultural community have been leaders in trying to plan for sustainability.

Carnegie Museums Emphasize Sustainability in 21st Century

Beyond transitioning to natural gas at the Bellefield Boiler, the Carnegie Museums are taking strides to be more sustainable, focusing on reduction of utility usage and decarbonization. Steam energy from the Bellefield Boiler continues to supply heat and humidity for the museums, while other energy needs, including chilled water, lighting, and HVAC, are supported through grid electricity (A. Young, personal communication, May 6, 2024). Currently, about 25% of grid electricity is sourced from renewable sources, with the goal of increasing this percentage. The museums use EnergySTAR Portfolio Manager to track energy use and emissions, and they partner with The Efficiency Network to create a customized plan for efficient upgrades (The Efficiency Network 2023). The museums are members of the Green Building Alliance (GBA) and Pittsburgh’s 2030 District, which seek to reduce emissions associated with commercial and institutional buildings by 50% from baseline measurements by 2030.

The museums honors a commitment use high quality construction for any new facilities, aligning with Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design LEED standards. As an example, the Carnegie Museum of Natural History’s Dinosaur Hall is LEED silver certified as of 2005 (Flom 2005). According to Vice President of Facilities, Planning, and Operations, Tony Young, the art museums have the highest energy demands of the four museums, largely due to the unique temperature and humidity demands to preserve the collection. Hence, they are currently investigating how to incorporate Seasonal Drift. Seasonal Drift is the growing practice of allowing for a set range of fluctuation in temperature and relative humidity, varying by season. This typically serves to conserve energy and cut costs (National Park Service, 2016).

Most recently, the Carnegie Music Hall underwent $9 million in renovations with accessibility in mind. These were the largest renovations in the space since it opened in 1895, with upgrades such as widening chairs, installing air conditioning for the space, and rewiring for LED bulbs (CJL Engineering 2024, Batz 2024). The Carnegie Museums are not alone in this work, as many community partners impact and are impacted by these changes. In particular, as a close neighbor which share a similar origin, Phipps Conservatory and Botanical Gardens has been an influential partner in Oakland’s continued sustainable development.

Phipps Conservatory and Botanical Gardens

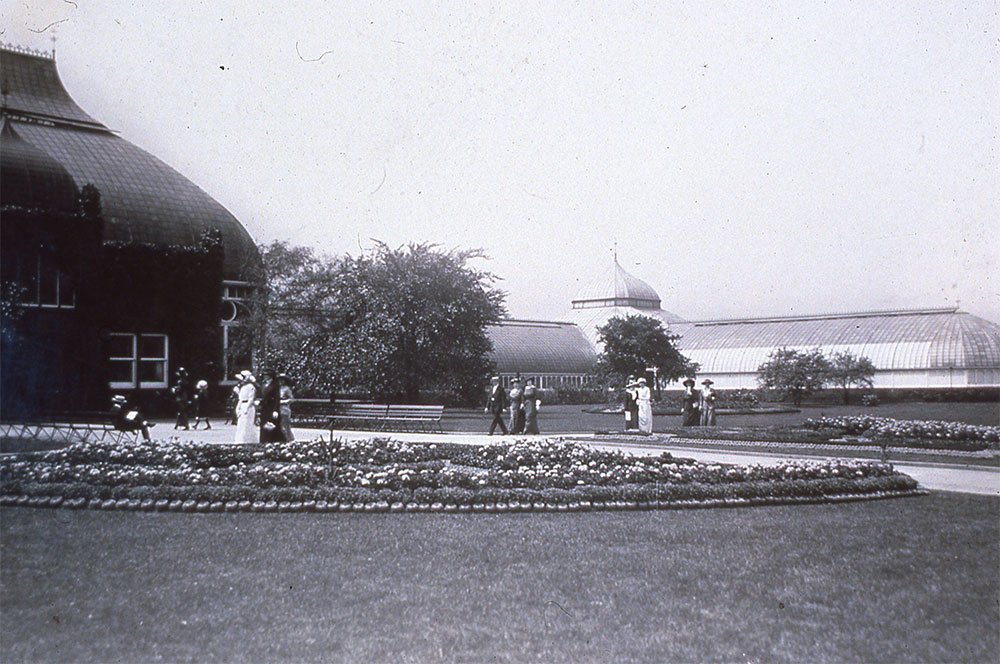

When Phipps Conservatory was founded in 1893, it was the largest and finest greenhouse in the United States (“Welcome Center”). Like Carnegie, Henry W. Phipps was a successful industrialist of the era, as the owner of the DuPont Powder Company and Kloman & Phipps Iron Mill, as well as a partner in the Carnegie Steel Company (Philanthropy Round Table). He shared Carnegies desire to invest in the community that shaped him, particularly by establishing parks and conservatories, supporting medical research, and developing affordable housing. In forming the Oakland conservatory, Phipps made clear his desire to “erect something that will prove a source of instruction as well as pleasure to the people” (Philanthropy Roundtable). When Phipps gifted the facility to the city, he stipulated that it remain open on Sundays to allow working people to visit. This replicated the success of an additional greenhouse he had developed on Pittsburgh’s north side.

Henry W. Phipps supported parks and conservatories to “prove a source of instruction as well as pleasure to the people.”

Image Source: Phipps Conservatory and Botanical Gardens

The original glass structure was designed by Lord & Burnham, a New York-based greenhouse manufacturing group ("A Gift to Pittsburgh"). The space opened with an exhibition of more than 6000 tropical plants - much like the Carnegie Museums, this exposed Pittsburgh residents to world in ways they likely never would have thought possible. In the fall of 1894, the first electric lighting was installed to allow people to view shows until 9 p.m. In 1895, 11 steam-heated propagation houses were added to the facility. In 1932, the city entered an agreement with the Carnegie Museums to connect Phipps Conservatory with the Bellefield Boiler steam system, however the significant infrastructure cost delayed this connection for more than 40 years (“Growth and Change”).

Early Photo of Phipps Conservatory’s Glass House

Image Source: Phipps Conservatory and Botanical Gardens

While the historic glass house was eye-catching, it was not constructed for energy efficiency, and years of deterioration caught up with the facility. In 1976, the facility was named a National Historic Landmark, which triggered a renewed investment in its preservation. In 1978, the conservatory underwent renovations totaling more than $3.2 million supporting plumbing, electrical and temperature control, and an underground steam line connecting the conservatory to the Bellefield Boiler ("The End of an Era").

Andrew Carnegie was inspired by Phipps’ philanthropic success, even referencing the development of Phipps Conservatory in the Gospel of Wealth (1889):

For my part, I think Mr. Phipps put his money to better use in giving the workingmen of Allegheny conservatories filled with beautiful flowers, orchids, and aquatic plants, which they, with their wives and children, can enjoy in their spare hours, and on which they can feed the love for the beautiful, than if he had given his surplus money to furnish them with bread, for those in health who cannot earn their bread are scarcely worth considering by the individual giver; the care of such being the duty of the state. The man who erects in a city a truly artistic arch, statue, or fountain makes a wise use of his surplus. Man does not live by bread alone.

Carnegie particularly commended Phipps’ decision to place the responsibility of ongoing care on the city to ensure that the public truly held ownership, stating that this action “secures for (Phipps Conservatory) forever the public ownership, the public interest, and the public criticism of their management.” The conservatory remained in public care until 1993, when the city transferred responsibility to Phipps Conservatory, Inc.

Phipps Today

When the conservatory transferred to private nonprofit management, Richard Piacentini was selected as the General Manager, and he remains at the helm today. Piacentini’s vision for the future of the institution put sustainability at the forefront. Since this time, Phipps Conservatory has made a number of capital investments to preserve the historic space and fill organizational needs, while promoting a more sustainable future. Currently, the Phipps Conservatory campus is home to three Living Building Certified structures, and four LEED certified structures (“Green Innovation at Phipps”).

In 2005, Piacentini took on one of the organization’s first green capital upgrades. Considering the future of guest experience in the space, they deemed that the addition of a welcome center would be critical to support business operations. A gift shop, cafe, and admissions area channeled additional revenue into the organization (“A Gateway to Sustainability”). The design was carefully considered to add needed space without obstructing the view of the famous glasshouse, all while prioritizing low lifetime emissions. This was a first of its kind for a public garden. Their strategy for this space involved both passive design and tech-based solutions, simulated with digital replicas. The welcome center’s is connected to weather station data to automate temperature and lighting controls, and uses an intelligent HVAC system that only conditions areas where people gather.

Phipps Conservatory and Botanical Gardens Welcome Center

Image Source: Phipps Conservatory and Botanical Gardens

Additional projects followed the success of the Welcome Center. In 2006, the organization expanded the Tropical Forest Conservatory, which uses design elements very little energy usage. In 2006, the new 36,000 square foot production greenhouse with LEED Platinum status. In 2012, they took on one of the most challenging sustainable building projects known at the time - the Center for Sustainable Landscapes.

The Center for Sustainable Landscapes is one of the greenest buildings in the world - the first and only building to meet seven of the highest green certifications (“Center for Sustainable Landscapes”, A. Haas, personal communication, Feb. 15, 2024). Completed in 2012, the space is used primarily for the office and educational space. The facility was constructed on a former brownfield site, previously used by the City of Pittsburgh public works department. The Center for Sustainable Landscapes is net zero in energy, generating more renewable energy than it uses through solar panels and a vertical axis wind turbine onsite. Heating and cooling is supported by geothermal wells far beneath the ground.

To maintain low levels of energy usage, the facility was constructed using a number of passive design elements, including south-facing windows to maximize sun exposure in the winter with tree coverage to create shade in the summer. There are also light shelves and sloped ceilings to direct sunlight through the space. Utilizing a green roof keeps temperature down and prevents rainwater runoff while making the roof structurally last longer. The facility has a network of sensors to automate actions like opening and closing windows or adjust lighting shelves based on real time weather conditions to maximize building efficiency.

Center for Sustainable Landscapes

Image Source: Phipps Conservatory and Botanical Gardens

Beyond energy use, the facility is also net positive in water consumption. Storm and sanitary water is captured and treated onsite using sand and UV light, and used for flush and janitorial water. irrigation. The conservatory is required to source all potable water through municipal services, though they do not return any waste water to city system, rather, overflow diverted to a lagoon which also adds to the facilities landscaping and biophilic design.

Aesthetically, biophilia is promoted throughout the facility to emphasize connections between nature and human health. As you walk into the space, one of the first features you may notice is the display of artwork, or their Biophilia Enhanced Through Art (BETA) project.

In 2019, Phipps Conservatory took on another opportunity through he Exhibit Staging Center (“Exhibit Staging Center”, A. Haas, personal communication, Feb. 15, 2024). Rather than starting from the ground up, this project was designed around retrofitting a former public works building sharing many successful techniques seen in the Center for Sustainable Landscapes. In addition to using this space for crafting exhibit pieces, it also houses a yoga studio, meditation room, and fitness center focused on staff wellness.

While new facilities on the Phipps Conservatory campus lead the way in environmental design, the organization still wrestles with ways to increase efficiency of their historic glasshouse. The organization is investigating ways to disconnect from the Bellefield Boiler and completely decarbonize the historic structure. With possible solutions ranging from geothermal energy, electrification, and passive earth tubes, this feat has not yet been accomplished in the field (The Climate Toolkit 2024).

Conclusion

Oakland has a complex history of development. Approaching neighborhoods with systemic models can be a strong environmental choice. While the Bellefield Boiler can power a large ecosystem of buildings with less waste than individual heating systems or larger grids, it likely is not the most sustainable long term solution. Retrofitting and adapting to is essential for meeting growing energy needs set against climate commitments. As innovative cultural organizations push the boundary on sustainable facilities, this will change the shape of energy use across the community. As demonstrated over the last century, recognizing the opportunity for collaboration with the anchor facilities like the Carnegie Museums and Phipps Conservatory and Botanical Gardens will be pivotal in future sustainable urban development.

-

“A Journey to France to Uncover the Mysteries of the Carnegie’s Grand Staircase.” Carnegie Museum of Natural History. Accessed May 16, 2024. https://carnegiemnh.org/a-journey-to-france-to-uncover-the-mysteries-of-the-carnegies-grand-staircase/.

Barlow, Kimberly. “University Times » Bellefield Boiler Plant Converts to Cleaner Fuel.” University Times, University of Pittsburgh. Accessed April 15, 2024. https://www.utimes.pitt.edu/archives/?p=8836.

Batz, Bob, Jr. “Restoring A ‘Palace of Music’ - Carnegie Magazine.” Carnegie Museums of Pittsburgh, February 28, 2024. https://carnegiemuseums.org/carnegie-magazine/spring-2024/restoring-a-palace-of-music/.

“Bellefield Boiler: A 113-Year-Old ‘Cloud Factory.’” University Wire. Carlsbad: Uloop, Inc, 2020. https://search.proquest.com/docview/2351328165?pq-origsite=primo.

Carnegie, Andrew. "Presentation of the Carnegie Library to the People of Pittsburgh," November 5, 1895. Printed by order of the Corporation of the City of Pittsburgh.

Carnegie Library of Pittsburgh. “History of Carnegie Library of Pittsburgh.” Accessed May 22, 2024. https://www.carnegielibrary.org/about/history-of-carnegie-library-of-pittsburgh/.

Carnegie Museums of Pittsburgh. “Our History.” Accessed April 8, 2024. https://carnegiemuseums.org/about-us/our-history/.

Department of Environmental Protection. “PA Mining History.” Accessed May 14, 2024. https://www.dep.pa.gov:443/Business/Land/Mining/Pages/PA-Mining-History.aspx.

Farr, Douglas. Sustainable Urbanism : Urban Design with Nature. Newark: John Wiley & Sons, Incorporated, 2004.

Flom, Laurie. “GREEN With Great Buildings.” Carnegie Online. Spring 2005. https://carnegiemuseums.org/magazine-archive/2005/spring/feature1.html.

Gangewere, Robert J. “BUILDING A PALACE OF CULTURE: ‘I Felt That Aladdin and His Lamp Had Been at Work.’” In Palace of Culture, 25–62. Andrew Carnegie’s Museums and Library in Pittsburgh. University of Pittsburgh Press, 2011. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctt5hjs27.6.

“GHG Facility Details.” Accessed May 20, 2024. https://ghgdata.epa.gov/ghgp/service/facilityDetail/2022?id=1005525&ds=E&et=&popup=true.

Grillo, Heather. “CJL Engineering Cools Down Carnegie Music Hall.” CJL Engineering, April 9, 2024. https://www.cjlengineering.com/cjl-engineering-cools-down-carnegie-music-hall/.

“Glasshouse Decarbonization - A New Climate Toolkit Goal.” The Climate Toolkit (blog), May 14, 2024. https://climatetoolkit.org/glasshouse-decarbonization-a-new-climate-toolkit-goal/.

“How Arts Organizations Drive Environmental Leadership Globally.” Https://Www.Environmentenergyleader.Com/ (blog). Accessed May 18, 2024. https://www.environmentenergyleader.com/2024/03/arts-organizations-leading-the-charge-for-environmental-stewardship/.

Institute of Medicine (US) Roundtable on Environmental Health Sciences, Research, Bernard D. Goldstein, Baruch Fischhoff, Steven J. Marcus, and Christine M. Coussens. “The Changing Face of Pittsburgh: A Historical Perspective.” In Ensuring Environmental Health in Postindustrial Cities: Workshop Summary. National Academies Press (US), 2003. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK222035/.

Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. 20540 USA. “Carnegie Institute, Pittsburgh, Pa.” Image. Accessed May 22, 2024. https://www.loc.gov/resource/det.4a22888/.

Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. 20540 USA. “Carnegie Steel Plant, Homestead, Pa.” Image. Accessed May 22, 2024. https://www.loc.gov/resource/det.4a06938/.

National Park Service. NPS Museum Handbook, Part I. “Chapter 4: Museum Collections Environment.” 2016.

“Natural Gas and the Environment - U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA).” Accessed May 13, 2024. https://www.eia.gov/energyexplained/natural-gas/natural-gas-and-the-environment.php

“Oakland: A Look Back Over the 20th Century.” Accessed April 8, 2024. http://exhibit.library.pitt.edu/oakland-a-look-back/.

Philanthropy Roundtable. “Henry Phipps Jr.” Accessed April 8, 2024.

“Phipps Center for Sustainable Landscapes | U.S. Green Building Council.” Accessed April 12, 2024. https://www.usgbc.org/projects/phipps-center-sustainable-landscapes.

https://www.philanthropyroundtable.org/hall-of-fame/henry-phipps-jr/.

Phipps Conservatory. “A Gift to Pittsburgh (1893 – 1930).” Accessed April 15, 2024. https://www.phipps.conservatory.org/visit-and-explore/explore/explore-our-history/the-story-of-phipps/a-gift-to-pittsburgh-1893-1930

Phipps Conservatory. “A New Beginning (1993 – Present).” Accessed April 15, 2024. https://www.phipps.conservatory.org/visit-and-explore/explore/explore-our-history/the-story-of-phipps/a-new-beginning-1993-present.

Phipps Conservatory. “Exhibit Staging Center | Phipps Conservatory and Botanical Gardens | Pittsburgh PA.” Accessed April 15, 2024. https://www.phipps.conservatory.org/green-innovation/at-phipps/exhibit-staging-cente

Phipps Conservatory. “Growth and Change (1930 – 1971).” Accessed April 15, 2024. https://www.phipps.conservatory.org/visit-and-explore/explore/explore-our-history/the-story-of-phipps/growth-and-change-1930-1971

Phipps Conservatory. “The End of an Era (1971 – 1993).” Accessed April 15, 2024. https://www.phipps.conservatory.org/visit-and-explore/explore/explore-our-history/the-story-of-phipps/the-end-of-an-era-1971-1993.

Phipps Conservatory. “Tropical Forest Conservatory | Phipps Conservatory and Botanical Gardens | Pittsburgh PA.” Accessed April 12, 2024. https://www.phipps.conservatory.org/green-innovation/at-phipps/tropical-forest-conservatory.

Phipps Conservatory. “Welcome Center | Phipps Conservatory and Botanical Gardens | Pittsburgh PA.” Accessed April 15, 2024. https://www.phipps.conservatory.org/green-innovation/at-phipps/welcome-center.

“Pittsburgh (Perhaps No Other City in America Has Been so Generously Endowed by Its Great Families as Pittsburgh).” Financial Post Magazine for the Moneywise (1990), 1996, 66-.

Susany, Louis M. “THE BELLEFIELD BOILER PLANT.” DISTRICT HEATING, 1967.

The Efficiency Network Blog. “TEN Launches New Set of Energy Initiatives at Carnegie Museums,” September 26, 2023. https://blog.tensaves.com/ten-launches-new-set-of-energy-initiatives-at-carnegie-museums/.

US Fed News Service, Including US State News. “Bellefield Boiler Plant in Oakland to Reduce Air Emissions.” February 20, 2009. https://www.proquest.com/docview/471717904/citation/80761A4ED0B447C3PQ/1.

York, Carnegie Corporation of New. “The Gospel of Wealth.” Carnegie Corporation of New York. 1889.

https://www.carnegie.org/publications/the-gospel-of-wealth/.