In Part I of this research, the National Digital Inclusion Alliance’s definition of digital inequity was used to describe the term as a condition in which all individuals and communities have the information technology capacity needed for full participation in our society, democracy, and economy. This is significant for the arts as artists and arts organizations are relying more on digital strategies for reaching audiences and increasing attendance. This article, as a continuation of digital equity and arts research, will explore the role digital media and arts plays in the continued efforts towards digital equity across the United States.

Since its release of the Top 40 Arts-Vibrant Arts Communities, SMU DataArts has released several articles highlighting various MSAs on its list. SMU DataArts defines an MSA as a community that is either a Micro- or Metropolitan Statistical Area. Metropolitan Statistical Areas have “at least one urbanized area of 50,000 or more population.” Micropolitan Statistical Areas have “at least one urban cluster of at least 10,000 but less than 50,000 population.” Cleveland, for example, was recently writing about, where the transition to virtual programming options allows for greater reach and new audiences. However, 26.5% of households are living without a laptop or desktop, and 46.2% of households making under $20,000 are living without a broadband subscription. Additionally, while access is widespread, as only 0.4% of residents lack access to broadband, 35.6% do not have access to adequate broadband speed.

This begs the question, which audiences are being reached? A closer look at Cleveland and surrounding areas using Microsoft Airband Initiative’s digital equity database shows the areas in blue where digital equity is higher and yellow where digital equity is lower. An aggregate of percentage means of the following factors is shown in the Greater Cleveland area in Figure 1:

● Percent of high schools without foundational CS course

● Households without a desktop or laptop

● Without access to broadband of any type

● Without internet subscription to broadband of any type

● Without broadband subscription in households with income <$20,000

Figure 1. Source: Microsoft Airband Initiative

What results is a visual representation of the effects of digital redlining. The Anti Digital Redlining Act of 2021, introduced to the House of Representatives by Rep. Yvette Clarke, defines digital redlining as “deploying or upgrading broadband service in a particular geographic area based on residents' race, income, or other factors.” -Tie to arts participation-

In this article, the following research questions will be addressed:

In cities where new media and digital arts are prevalent, where does their digital equity score fall in relation to engagement in this art medium?

How does digital inequity correlate with arts participation?

This article discusses the potential role of new media and digital arts in the fight toward digital equity, compares barriers to digital participation with arts participation, and explores the role of libraries as critical players in combatting digital inequity.

Digital arts as a tool for equity

These research questions were developed with some ideas extrapolated by new media artist Agnes Chavez in mind. In a complementary NEA essay to the Tech as Art report, Chavez states that ”fostering a positive attitude for using digital media is an important first step for closing the digital divide.” Digital arts being a part of STEAM learning initiatives can help foster this positive attitude in many ways. Integrating digital arts into STEM curricula can help engage students more deeply, offering them new avenues for critical thinking when it comes to why they are using certain technology, not just how. Higher levels of learning are complemented with career preparation as students are provided with highly-sought computing skills. STEAM also highlights equity, inclusion, and accessibility issues in STEM fields and in the world at large. As inequities penetrate STEM fields at the same time as the importance of these fields is growing, Chavez explains why integrating the arts into STEM learning matters more than ever:

“We face unprecedented challenges, and if we are to create equitable responses, we must begin to develop numerous literacies. Students can develop understanding and empathy while exploring the applications of science and technology in our societies. They do not need to end up working in related fields to benefit from acquiring humanistic and scientific literacy—and ensuring that they do so will in turn benefit society and the world.”

Chavez is involved in several STEAM education and digital and new media arts educational projects. She is a co-founder of the Paseo Project, the goal of which is to expose members of their community to 21st century skills, contemporary art practices, and exciting new ways to engage with the world. This organization focuses on STEAM educational projects and workshops for students. She is also the Founder and Director of the STEMarts Lab in Taos, New Mexico. STEMarts uses strategies to help participants in underserved communities move from being passive consumers of technology to cultural producers, empowered with the technology to tell their own stories. As Chavez states, it operates under the assumption that “an understanding of art, science, and technology expands our understanding of ourselves and our relationship to nature and society.” Figure two below illustrates the model based on this assumption.

Figure 2. Source: STEMarts Lab

For this research, one objective was to look for digital and new media artists and programs doing similar projects for underserved youth. A web search found none. While nothing was found, that isn’t to say these types of programs don’t exist in the identified MSAs. Chavez’s work demonstrates the possibilities in new media and digital arts to make a broader positive impact regarding digital equity. There is a direct connection between the arts and a positive impact on society at large. The hope of this research is to provide a compelling foundation for this link to support a framework for further research and application.

Methodology

Because z-scores can’t be aggregated and averaged across categories, each digital equity category was analyzed separately. Z-scores below 0 were noted for all MSAs across categories. The following MSAs scored above 0 in each digital equity category:

Boulder, CO

Bozeman, MT

Cambridge-Newton-Framingham, MA

Frederick-Gaithersburg-Rockville, MD

Portland-Vancouver-Hillsboro, OR

Salt Lake City, UT

Washington-Arlington-Alexandria, DC-VA

The following MSAs in which digital arts and media may be prevalent were also looked at due to their reputations for having highly active arts and technology sectors:

Austin-Round Rock-Georgetown, TX

Chicago-Naperville-Arlington Heights, IL

Los Angeles-Long Beach-Glendale, CA

New York-Jersey City-White Plains, NY-NJ

San Francisco-Redwood City-South San Francisco, CA

Seattle-Bellevue-Everett, WA

Arts Participation aligned with Digital Inequity

Direct linkage from a high level of digital equity to a strong digital arts presence could not be verified from the brief search done on each MSA. This research, much like in Part I, points to the fact that each of these cities is different and not comparable to another. Whether one city is doing “better” than another regarding digital equity efforts is not an objective measure of progress. And sufficient data was not available to conclude whether or not there is a relationship between digital arts and digital equity. However, a few notable differences among MSAs are worth mentioning.

New York City, for example, is known for being one of, if not, the, top city in the US for visual arts, including digital arts and new media. Its digital arts and new media scene has been developing over the past few years. The Hall des Lumières, an immersive digital arts center, opened in Manhattan in September 2022. New York is also home to ARTECHOUSE, an organization dedicated to the intersection of art, science and technology, among many independent digital artists. It is commensurate with Seattle in terms of a world-class digital arts environment. Seattle is home to the world’s first NFT Museum, which opened in January 2022. The city also has a large presence of freelance digital artists and digital arts programs offered at local universities. In comparing technology and digital equity initiatives between the two cities, New York City is focused more on advancing technology and innovation while ensuring broadband access to all residents. Seattle has a comprehensive plan that focuses on eliminating barriers to digital equity for vulnerable, historically underserved, or underrepresented residents, small businesses, organizations, and communities.

San Francisco has also been at the forefront of the digital arts world. SFMOMA’s Department of Media Arts established the museum as a leader in the presentation, collection, and preservation of time-based media works. Another notable San Francisco organization includes the Museum of Art and Digital Entertainment (MADE). The Digital Arts & Technology program at Sunset Youth Services offers an educational experience for youth, focusing on creative self-expression and building marketable skills. The city has also expanded efforts, as stated in its 2019 Digital Equity Strategic Plan, to address the many facets of digital equity, including affordability, literacy, and accountability on the part of an open coalition.

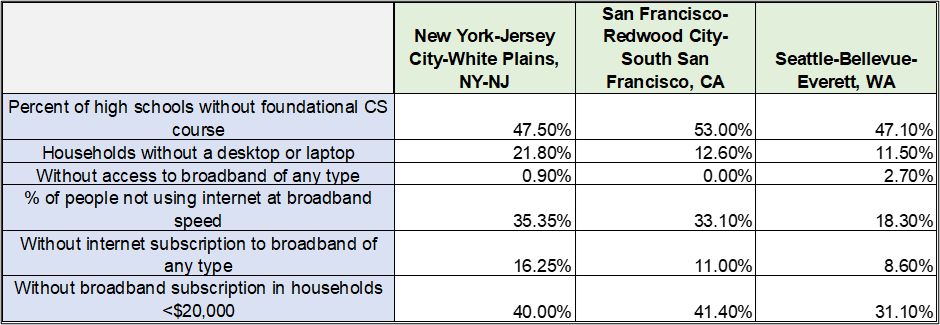

Each city is actively pursuing digital equity efforts, given its unique history and challenges. Going into the minutiae of progress and comparing it across cities using multiple variables would get complex very quickly. Add to that the relatively niche area of digital arts, new media, and STEAM programming and how those elements fit into that progress and it could be a thesis all its own. Figure 3 shows a summary of New York City, San Francisco, and Seattle MSAs’ six digital equity categories identified throughout this research.

Figure 3. Source: Author

A brief comparison of all MSAs’ (mostly large) digital equity plans looked for involvement of artists and/or arts organizations in digital equity initiatives, committees, leadership roles, strategies, and areas of digital inequity being targeted (literacy, access, and affordability). Chicago’s 2023 Digital Equity Plan was the only one mentioning an arts organization, the Kehrein Center for the Arts, which is involved as a community workshop host and partner. This exemplifies a strategy mentioned in Bridging The Digital Divide: Arts And Digital Placemaking which is that arts organizations can open their space for events centered around digital equity, such as literacy classes or discussions with community leaders.

Some of the most comprehensive plans included Austin, Chicago, Portland, Seattle, and San Francisco, which addressed all facets of digital inequity. These plans also contained a critical commonality, which was a strategy to leverage community assets and promote community involvement. While none of these plans explicitly mentioned the arts, Chicago’s plan included “digital media” in its definition of the creative sector/industries.

Arts Participation, digital participation

Historically, communities of color have been less likely to participate in the arts due to a number of barriers where race plays a major role. A 2021 study on arts engagement investigated the impacts of social inequities on arts engagement. Researchers found that in comparison to white participants, Black participants had a 34% lower likelihood of attendance. The study also found that socioeconomic factors impacted the likelihood of participating in arts events. Higher levels of income and social class were associated with an increasing likelihood of attendance. A 2021 study on race, ethnicity, and museum participation corroborates this history of exclusion in arts enterprises. Alexandra Olivares and Jaclyn Piatak found a significant gap between Black and white arts participation, where Black individuals are 32% less likely to attend an art exhibit than white individuals.

Many arts organizations are taking to social media platforms to market their events or are using digital marketing strategies to gain a broader audience. One such strategy involves the creation of audience personas, in which organizations construct semi-fictional characters that embody their target audience. These personas encapsulate trends among the particular demographic, geographic, and psychographic factors that make them up, including technology use. This strategy helps determine the best way to communicate with potential new audiences based on the most preferred method of contact for a given persona, be it email, social media, print, or public-facing ads. While this is a helpful tool for arts organizations attempting to streamline their marketing tactics, there’s a danger in such strategies in excluding community members because they lack digital capital.

Researcher Sora Park has written extensively about various forms of digital inequity. In her book Digital Capital, she ties this concept to an individual’s existing socioeconomic status. Digital capital consists of several elements, all of which contribute to shaping a user’s digital technology ecosystem. Much like an individual’s physical ecosystem, this provides them with the infrastructure, access, skills, and general attitude toward their digital environment. In a separate paper, Dimensions of Digital Media Literacy and the Relationship with Social Exclusion, Park uses the term “information poverty” to describe the inability to use or access information and communications technology. She classifies this term as being an indicator of social exclusion. In Digital Capital, Park also posits that information is critical to how the digital society adds value and redistributes power. Revisiting the practice of digital redlining, in which Internet providers purposefully underinvest in lower income communities, communities of color, as well as rural communities, are disproportionately affected and therefor face greater information poverty.

Digital wealth is quickly growing into a secondary class system in which those lacking access, affordability, and skills face additional barriers to fully participating in society. The accumulation of digital capital in parts of the population is much more rapid than the rate at which digital deficiencies are being filled, leaving some much more excluded from society. Sharon Strover labeled feeling like everyone else in terms of digital participation as digital dignity. Along with digital skills and literacy, affordability, and access, the moral argument of digital inclusion must not be forgotten. Until everyone gains the capacity to participate in digital society, the arts cannot call themselves equitable and inclusive. Their power and ability to engage in digital equity efforts, however, is limited. It would be unreasonable to expect arts organizations to tackle an issue as complex as digital inequity. Rather, a growing body of research identifies libraries as entities well-suited for such a role.

Libraries drive digital equity

Several academic studies agree that libraries are well-positioned to address digital inequity in their communities. Historically, they are one of the most inclusive public institutions by their nature. Strover described libraries as having a unique role in broadening access to a range of materials and information and encouraging all people to use their resources. As of 2019, there are 9,057 public libraries in the United States. Each of those public libraries has the potential to be an avenue for access, affordability, and literacy and skills training in their respective communities. The case of a New York City public library undertaking illustrates this potential.

In her 2019 article, “Public Libraries and 21st-century Digital Equity Goals,” Sharon Strover discussed an example of a library instituting a mobile hotspot program to increase digital access. New York Public Library (NYPL) implemented the Library HotSpot program in 2014 to provide free Wi-Fi to New York City’s residents lacking home internet access. This program was developed to support former Mayor Bill de Blasio’s goal of providing high-speed residential internet service for low-income communities without internet service by 2025. The following excerpt demonstrates the impact of this program on residents:

“Approximately 65.0% of the users reported greater confidence in their ability to use the internet since having the hotspot. The data show a significant correlation between the volume of hotspot use and self-assessed capabilities.”

While libraries generally have this ability and are often expected to offer digital services, many face similar challenges to arts nonprofit organizations. Because their funding comes from the government, they must often advocate for greater funding to support their public services. The NYPL mobile hotspot program only occurred because of support from foundations. In early April this past year, New York City announced plans to cut the city’s library funding by $23 million, after city agencies were already asked to cut their existing budgets by 4%. After facing intense public backlash, however, city officials rescinded this proposal. The irony of this proposal just a few years after the city made plans to increase digital access does not go unnoticed. Concurrently, the state of Missouri recently announced its plan to cut library funding. This plan comes as nearly 20% of Missouri’s population is living without an internet subscription, 25% do not have a desktop or laptop. Additionally, 44% of households with an annual income of under $20,000 do not have an internet subscription.

a new digital inequity framework

During the process of writing this article, two intriguing pieces of information were released. The first is a report published by SMU DataArts titled Local Arts Agency Funding and Arts Vibrancy. In this subsequent report to Top 40 Most Arts-Vibrant Cities in the U.S., SMU analyzed the impact local arts agencies (LAAs) have on overall arts vibrancy of the community in which they serve. The following quote exemplifies and summarizes their findings.

“LAAs are catalysts for arts vibrancy in communities throughout the country. The more grant dollars they have to invest in artists and arts organizations, and the more programs and services they provide, the more their communities pulse with arts-driven creative and economic life, vigor, and activity.”

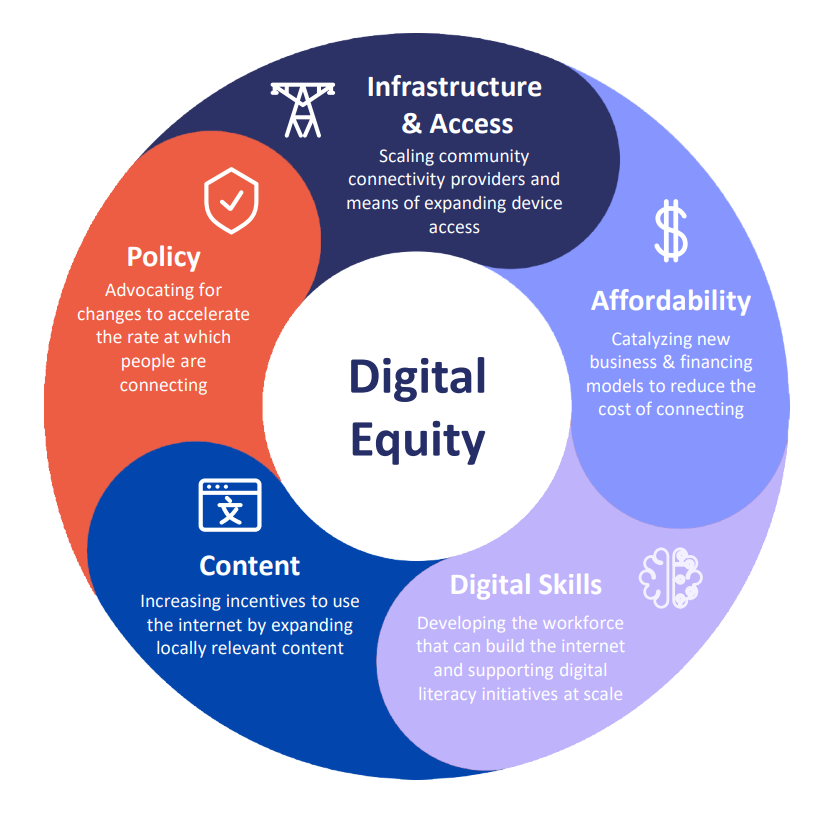

The second is State of Digital Inequity data dashboard, the result of a collaboration between Connect Humanity, TechSoup Global Network, Civicus, Forus, WINGS, NTEN, and others. In addition to access, affordability, and literacy, this research takes into account content and policy for achieving a digitally equitable state. The areas of content and policy, summarized in Figure 4, are added to the previously-known digital equity framework by Connect Humanity.

This dashboard is the output of survey responses from over 7,500 participants in 136 countries. Representatives and constituents of civil society organizations (CSOs), 4% of which related to the arts, were surveyed to gauge both how important technology is in serving their missions, and to what extent the digital divide impacts their ability to work. One of the most significant findings in this study was that 95% of organizations said the internet is vital to their ability to do their work, yet three in four said that a lack of internet access, tools, or skills limits their ability to serve their communities effectively. This statistic aligns with a finding from the American Alliance of Museums’ 2023 TrendsWatch report, which found that globally, 76% of museum workers feel they are unequipped to operate in a “digital-first world,” and less than a third are actively involved in some form of digital skills training. Much like for audiences, it is just as critical to address these gaps in arts workers to ensure that this increasing digital infrastructure doesn’t “exacerbate existing inequalities in income and employment.”

These two resources focus on completely different scopes (local versus global) but highlight a similar key point. Local efforts have the potential to create the most impact, as communities are highly reliant upon and entrust local entities to provide the services they need. This amplifies the role arts organizations can play in promoting digital equity in their communities.

looking ahead

Part 3 will address the fourth research question:

How, if at all, are arts organizations filling digital equity gaps in their communities?

While it seems that few arts organizations are involving themselves in promoting digital equity,

the critical first step toward this cannot be stated enough – joining the conversation to develop

an understanding of how an existing inequitable system has led to inequity in the digital age.

Libraries are the institutions leading the effort toward digital equity and inclusion. A deeper dive

into libraries’ roles in this issue will uncover their similarities to arts organizations, including the

public support challenges they face. Part 3 will also highlight some discussions on digital

inequity in the arts starting to take place, including one conversation being led by the NEA. An

understanding of the broader societal impacts of digital inequity and current national, state, and

local policies attempting to eradicate it will ultimately help arts organizations gain a better

understanding of this novel barrier to the arts.

-

“ARTECHOUSE NYC.” Artechouse. Accessed May 4, 2023. https://www.artechouse.com/location/nyc/.

"All Info - H.R.4875 - 117th Congress (2021-2022): Anti Digital Redlining Act of 2021." Congress.gov. August 2, 2021. https://www.congress.gov/bill/117th-congress/house-bill/4875/all-info.

Chavez, Agnes. “How Artists Can Bridge the Digital Divide and Reimagine Humanity.” National Endowment for the Arts. June 2021. Accessed November 18, 2022. https://www.arts.gov/impact/media-arts/arts-technology-scan/essays/how-artists-can-bridge-digital-divide-and-reimagine-humanity.

“Chicago Digital Equity Plan.” Chicago Digital Equity Coalition. January 2023. https://www.chicago.gov/content/dam/city/sites/digital-equity-council/pdf/Digital-Equity-Plan-2023.pdf.

“City and County of San Francisco Digital Equity Strategic Plan 2019-2024.” City and County of San Francisco. 2019. https://sfmohcd.org/sites/default/files/SF_Digital_Equity_Strategic_Plan_2019.pdf.

“Digital Arts & Technology.” Sunset Youth Services. Accessed May 4, 2023. https://www.sunsetyouthservices.org/digital-arts-and-technology.

“Digital Equity: Explore.” Microsoft Airband Initiative. Accessed April 22, 2023. https://app.powerbi.com/view?r=eyJrIjoiM2JmM2QxZjEtYWEzZi00MDI5LThlZDMtODMzMjhkZTY2Y2Q2IiwidCI6ImMxMzZlZWMwLWZlOTItNDVlMC1iZWFlLTQ2OTg0OTczZTIzMiIsImMiOjF9.

“Digital Equity Initiative Action Plan Phase 2: From Vision to Action.” City of Seattle. 2016. https://www.seattle.gov/documents/Departments/Tech/DigitalEquity_PhaseII.pdf.

Frommer, Pauline. “The Largest Immersive Digital Arts Center in North America Opens in New York City.” Frommer’s. September 19, 2022. https://www.frommers.com/blogs/arthur-frommer-online/blog_posts/the-largest-immersive-digital-arts-center-in-north-america-opens-in-new-york-city.

Hays, Gabrielle. “Missouri House Republicans want to defund libraries. Here’s why.” PBS. April 14, 2023. https://www.pbs.org/newshour/politics/librarians-say-a-missouri-house-proposal-to-eliminate-library-funding-would-have-devastating-ripple-effects.

“Library Statistics and Figures: Number of Libraries in the United States.” American Library Association. Updated February 3, 2023. https://libguides.ala.org/c.php?g=751692&p=9132142.

Little, Chantelle. “How to create audience personas – a beginner’s guide.” Tiller Digital. February 25, 2021. https://tillerdigital.com/blog/how-to-create-audience-personas-a-beginners-guide/.

Matko, Meg and Jake Sinatra “Cleveland Scores Highest Among Midwestern Communities on Two Key Measurements of Arts Vibrancy.” SMU DataArts. April 13, 2023. https://culturaldata.org/learn/data-at-work/2023/cleveland-oh-arts-vibrancy-2022/.

“Media Arts.” SFMOMA. Accessed April 23, 2023. https://www.sfmoma.org/artists-artworks/media-arts/.

“New York City to Close Digital Divide for 1.6 Million Residents, Advance Racial Equity.” City of New York. October 28, 2021. https://www.nyc.gov/office-of-the-mayor/news/724-21/new-york-city-close-digital-divide-1-6-million-residents-advance-racial-equity.

“Our Methodology.” SMU DataArts. Accessed February 12, 2023. https://culturaldata.org/arts-vibrancy-2022/methodology/.

Park, Sora. Digital Capital. London: Palgrave Macmillan UK, 2017. https://doi.org/10.1057/978-1-137-59332-0.

Quaintance, Zack. “What Is Digital Redlining? Experts Explain the Nuances.” GovTech. March 28, 2022. https://www.govtech.com/network/what-is-digital-redlining-experts-explain-the-nuances.

Ravipati, Sri. “NYC Libraries to Offer 5,000 WiFi Hotspots to Students, Families.” The Journal. October 7, 2016. https://thejournal.com/articles/2016/10/07/nyc-libraries-to-offer-5000-wifi-hotspots-to-students-families.aspx.

Russo, Melissa. “Mayor Calls Off Proposed NYC Library Cuts After Public Backlash.” NBC New York. April 26, 2023. Updated on April 27, 2023. https://www.nbcnewyork.com/news/local/mayor-eric-adams-backs-down-from-cuts-to-nyc-public-libraries-in-latest-proposed-budget/4280158/.

Scorse, Yvette. “What Is Digital Inequity?” National Digital Inclusion Alliance. October 6, 2021. https://www.digitalinclusion.org/blog/2021/10/06/what-is-digital-inequity/.

“State of Digital Inequity: Civil Society Perspectives on Barriers to Progress in our Digitizing World.” Connect Humanity. Accessed May 4, 2023. https://connecthumanity.fund/digital-inequity-report/.

“Strategic Plan 2022.” New York City Office of Technology and Innovation. October 2022. https://www.nyc.gov/assets/oti/downloads/pdf/about/strategic-plan-2022.pdf.

Strover, Sharon. “Public Libraries and 21st Century Digital Equity Goals.” Communication Research and Practice 5, no. 2 (April 3, 2019): 188–205. https://doi.org/10.1080/22041451.2019.1601487.

Talbott, Chris. “New Seattle NFT Museum aims to highlight digital artists, educate art lovers about billion-dollar trend.” The Seattle Times. January 4, 2022. Updated January 4, 2022. https://www.seattletimes.com/entertainment/visual-arts/new-seattle-nft-museum-aims-to-highlight-digital-artists-educate-art-lovers-about-billion-dollar-trend/.

“Tech as Art: Supporting Artists Who Use Technology as a Creative Medium.” National Endowment for the Arts. June 2021. Accessed November 18, 2022. https://www.arts.gov/impact/research/publications/tech-art-supporting-artists-who-use-technology-creative-medium.

“The New York City Internet Master Plan.” NYC Mayor’s Office of the Chief Technology Officer. January 2020. https://www.nyc.gov/assets/cto/downloads/internet-master-plan/NYC_IMP_1.7.20_FINAL-2.pdf.

“The Top 40 Arts-Vibrant Communities of 2022.” SMU DataArts. Accessed February 12, 2023. https://culturaldata.org/arts-vibrancy-2022/the-top-40-list/.

“TrendsWatch: Building the Post-pandemic World.” American Alliance of Museums. 2023. https://www.aam-us.org/programs/center-for-the-future-of-museums/trendswatch-building-the-post-pandemic-world-2023/#form.

Voss, Dr. Zannie and Dr. Glenn Voss. “Local Arts Agency Funding and Arts Vibrancy.” SMU DataArts. May 2023. https://culturaldata.org/local-arts-agency-funding-and-arts-vibrancy/overview/.