When it comes to the widely discussed topic of mental health, the arts have proven to play a significant role in healing. In fact, artists and scientists have been researching impacts of art on the brain and body for nearly 75 years. The founding hypothesis in art therapy research emerged from the projects of two women curious about how art could help the severely ill, but extensions of their work continue to grow. Like much in our lives, art therapy research is now increasingly embracing immersive technology.

Art Therapy Then and Now

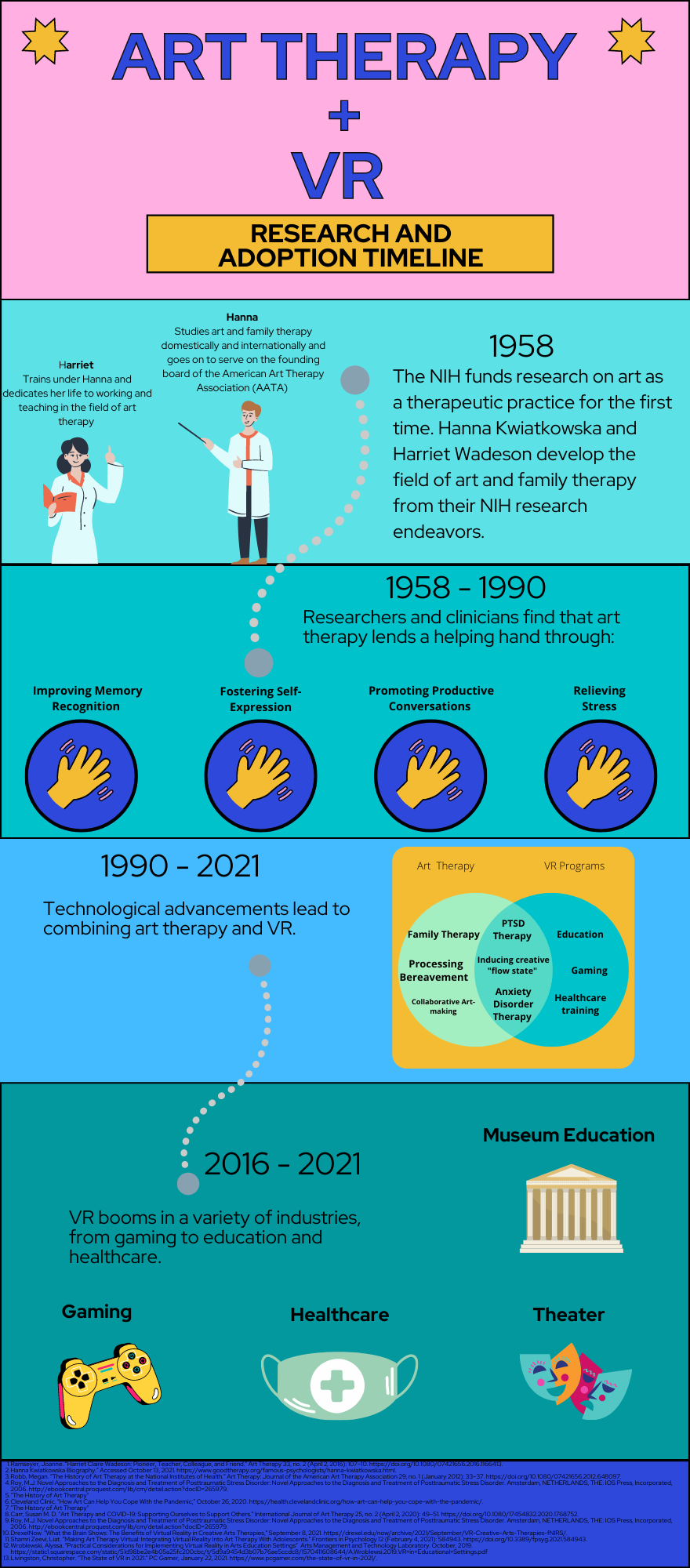

In 1958, the National Institutes of Health (NIH) funded research on art as a therapeutic practice for the first time at the agency’s Clinical Research Center and employed Polish sculptor turned therapist Hanna Kwiatkowska as the manager of this endeavor. Kwiatkowska is credited with birthing the field of art and family therapy through this project, and her research theorized that the process of art-making both aids hospital patient recovery and patient-family relations by uncovering dynamics indeterminable via verbal conversation. Kwiatkowska’s trainee at the time, Harriet Wadeson, began testing art therapy in other adult psychiatry areas and expanding our knowledge of its healing effects. Notably, Wadeson created an award-winning exhibit for the NIH called “Portraits of Suicide,” which demonstrated how patient-created art pieces can serve as important indicators of their mental health.

Harriet Wadeson’s “Portraits of Suicide.” Source: Music Institute of Chicago

Since Kwiatkowska and Wadeson’s pioneering research, clinicians have found art therapy to be beneficial in PTSD, eating disorder, and dementia treatment plans. The COVID-19 pandemic introduced society to other therapeutic benefits of art outside of clinical settings as well. For example, Cleveland Clinic’s Tammy Shella encouraged the public to make art in their homes during the pandemic, stating that creative expression helps individuals process difficult experiences and enter into a mindful and positively focused “flow state.” Those who adopted a new creative hobby during quarantine may have also benefitted from art’s immunity boosting response, hope-inducing power, and assistance in bereavement. Theories on art therapy have expanded across all art domains, and they speak to advantages of art-making both in and out of traditional healthcare settings. Today, the benefits of art-making are being tested on new technological frontiers, particularly VR.

The Health and Educational Effects of VR

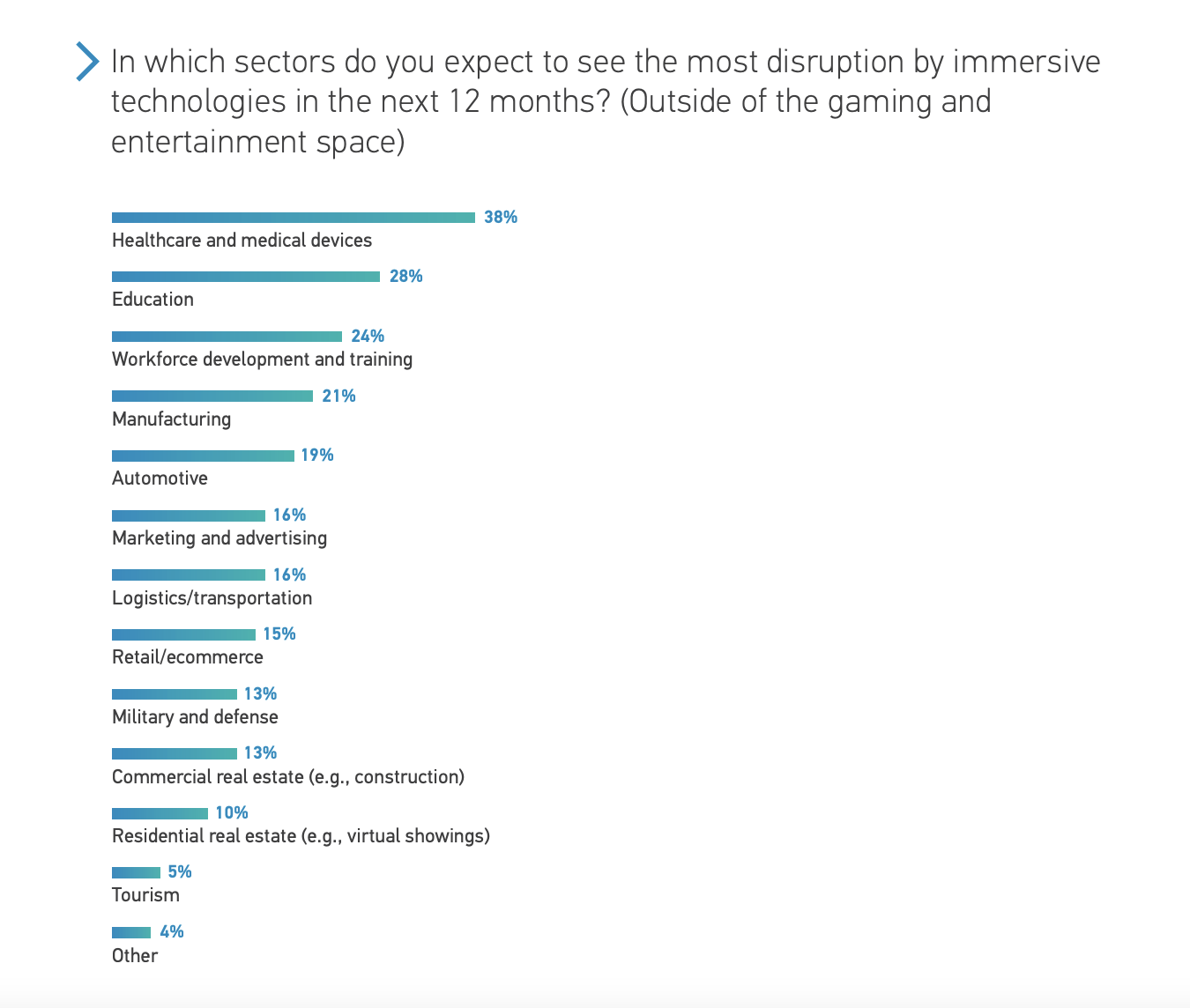

According to Greenlight Insights, 78% of Americans are familiar with VR technology. Users with experience in the technology’s multidimensional worlds will likely recognize their usage in the gaming industry, however, VR is now leading a growing parade of applications beyond gaming. One 2020 survey found that those involved with VR technology project it will grow most in the healthcare and education industries within the next year.

A visualization showing how VR development is disrupting health and education. Source: 2020 Augmented and Virtual Reality Survey Report.

The healthcare industry is currently using VR to train surgeons for procedures due to its incredibly lifelike simulations. VR also functions as a method of physical therapy and exercise for those who have injuries or disabilities. In the mental health space, therapists have been using combat simulations in VR since the late 1990s to facilitate safe and controlled processing of war veterans’ PTSD symptoms. VR exposure therapy has also helped 9/11 survivors soften and overcome effects of the event’s traumas. Ultimately, scientists believe VR assists PTSD patients because its immersive imagery helps unlock memories buried in the brain as a symptom of the disorder.

VR experiences exist in the education sector in natural history museum and art museum exhibits (Museum of Ancient Wonders, V&A), theaters (The Under Presents), and visual art settings. Some have even taken the technology as far as to build an entire visual art museum virtually (VOMA). In each of these applications, VR takes elements of art to another dimension through projecting all-encompassing imagery, sound, and emotion to its users. Therefore, scientists have taken a parallel path to art therapists when studying VR’s impact on the body and mind.

Infographic: Art Therapy Research and Application Timeline. Created by author.

Art therapy studies are shifting toward researching what art-making in VR programs can do for the brain. For example, a recent Drexel University study took a neuroscientific approach to VR research and concluded that painting within the technology’s Tilt Brush application calms the body by lowering prefrontal cortex activity. When clinicians tested Tilt Brush in a therapy setting with adolescents, they found that the technology seemed to make these younger patients more expressive than traditional art therapy methods. This may signal that the digital native generation has more confidence and comfort engaging with their creative side via technology than material methods. Art therapists who tested Tilt Brush themselves came to a similar conclusion. They noted that the technology would likely enhance creative processing for independent or introverted individuals because it would allow them to express themselves without judgement. The creative freedom that novel VR applications bring is one key benefit of the technology that contributes to its potential future as an educational and artistic aid.

Art created by a participant in Drexel’s study pairing neuroscience and VR. Source: DrexelNOW

Implications for Arts Institutions

Since VR is used in healthcare and almost all forms of art, from visual art to theatre, it is possible that adding VR components to art and culture programming could provide therapeutic benefits. The remaining question is how art institutions will choose to implement VR in health-focused community programs. Adding immersive experiences to community programming may foster collaborative creativity in communities and lessen short-term stress. However, because the technology is still developing in many ways, there are risks to adoption. For instance, VR technology may promote escapism in its audiences or potentially trigger users to trauma, given its immense power to imitate reality. The cost of the technology (~$300 for the Oculus Quest 2 headset) may be prohibitive to small institutions as well.

Kwiatkowska and Wadeson first scratched the surface toward understanding what art can do for societal health, and technology is further illuminating opportunities for more artistic impacts with VR. If market projections are correct, VR development and consumption will continue to grow, which will likely correlate with a reduction in adoption cost. As society becomes more comfortable with VR applications and they infiltrate our entertainment and public health schemas, it will be up to arts institutions to decide whether to adopt this technology to aid community development and healing initiatives. Regardless of the ultimate decision, in 2021, this thought is worthy of consideration.

+ Resources

“A.Wroblewsi.2019.VR+in+Educational+Settings.Pdf.” Accessed October 18, 2021. https://static1.squarespace.com/static/51d98be2e4b05a25fc200cbc/t/5d9a9454d3b07b76ae5ccdc8/1570411608644/A.Wroblewsi.2019.VR+in+Educational+Settings.pdf.

Alzheimer’s Disease and Dementia. “Art and Music.” Accessed October 18, 2021. https://alz.org/help-support/caregiving/daily-care/art-music.

American Alliance of Museums. “Evaluating the Impact of Augmented and Virtual Reality,” January 15, 2021. https://www.aam-us.org/2021/01/15/evaluating-the-impact-of-augmented-and-virtual-reality/.

American Alliance of Museums. “Immersion in Museums: AR, VR, or Just Plain R?,” October 25, 2018. https://www.aam-us.org/programs/center-for-the-future-of-museums/immersion-in-museums-ar-vr-or-just-plain-r/.

American Art Therapy Association. “American Art Therapy Association.” Accessed September 23, 2021. https://arttherapy.org/.

Anna dream brush. Live Performance at the Louvre Museum Paris (Virtual Reality Art), 2018. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Zs3n07Clw7A.

“Art_Therapy_and_Clinical_Neuroscience_----_(Part_II_The_Ideas).Pdf,” n.d. Bucharová, Monika, Andrea Malá, Jiří Kantor, and Zuzana Svobodová. “Arts Therapies Interventions and Their Outcomes in the Treatment of Eating Disorders: Scoping Review Protocol.” Behavioral Sciences 10, no. 12 (December 9, 2020): 188. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs10120188.

Carr, Susan M. D. “Art Therapy and COVID-19: Supporting Ourselves to Support Others.” International Journal of Art Therapy 25, no. 2 (April 2, 2020): 49–51. https://doi.org/10.1080/17454832.2020.1768752.

Cleveland Clinic. “How Art Can Help You Cope With the Pandemic,” October 26, 2020. https://health.clevelandclinic.org/how-art-can-help-you-cope-with-the-pandemic/.

Culture Geek. “Museums and Virtual Reality,” February 12, 2021. https://culturegeek.com/article/museums-and-virtual-reality/.

Cuperus, Anne A., Fayette Klaassen, Muriel A. Hagenaars, and Iris M. Engelhard. “A Virtual Reality Paradigm as an Analogue to Real-Life Trauma: Its Effectiveness Compared with the Trauma Film Paradigm.” European Journal of Psychotraumatology 8 (2017): 1–8. http://dx.doi.org.cmu.idm.oclc.org/10.1080/20008198.2017.1338106.

DrexelNow. “What the Brain Shows: The Benefits of Virtual Reality in Creative Arts Therapies,” September 8, 2021. https://drexel.edu/now/archive/2021/September/VR-Creative-Arts-Therapies-fNIRS/.

Hacmun, Irit, Dafna Regev, and Roy Salomon. “Artistic Creation in Virtual Reality for Art Therapy: A Qualitative Study with Expert Art Therapists.” The Arts in Psychotherapy 72 (February 1, 2021): 101745. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aip.2020.101745.

“Hanna Kwiatkowska Biography.” Accessed October 13, 2021. https://www.goodtherapy.org/famous-psychologists/hanna-kwiatkowska.html.

“IOS Press Ebooks - Novel Approaches to the Diagnosis and Treatment of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder.” Accessed October 18, 2021. https://ebooks.iospress.nl/volume/novel-approaches-to-the-diagnosis-and-treatment-of-posttraumatic-stress-disorder.

Jing Culture and Commerce. “Museum Of Ancient Wonders Plays Host To Ubisoft’s VR Escape Room Experience,” September 23, 2021. https://jingculturecommerce.com/museum-of-ancient-wonders-moaw-ubisoft-vr-escape-room/.

Kaimal, Girija, Katrina Carroll-Haskins, Marygrace Berberian, Abby Dougherty, Natalie Carlton, and Arun Ramakrishnan. “Virtual Reality in Art Therapy: A Pilot Qualitative Study of the Novel Medium and Implications for Practice.” Art Therapy: Journal of the American Art Therapy Association 37, no. 1 (January 2020): 16–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/07421656.2019.1659662.

Leaman, Suzanne, Barbara Olasov Rothbaum, JoAnn Difede, Judith Cukor, and Maryrose Gerardi. “Treating Combat-Related PTSD With Virtual Reality Exposure Therapy,” n.d., 28.

Lee, Hyunae, Timothy Hyungsoo Jung, M. Claudia tom Dieck, and Namho Chung. “Experiencing Immersive Virtual Reality in Museums.” Information & Management 57, no. 5 (July 1, 2020): 103229. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.im.2019.103229.

Livingston, Christopher. “The State of VR in 2021.” PC Gamer, January 22, 2021. https://www.pcgamer.com/the-state-of-vr-in-2021/.

McLay, Robert N., Dennis P. Wood, Jennifer A. Webb-Murphy, James L. Spira, Mark D. Wiederhold, Jeffrey M. Pyne, and Brenda K. Wiederhold. “A Randomized, Controlled Trial of Virtual Reality-Graded Exposure Therapy for Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder in Active Duty Service Members with Combat-Related Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder.” Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking 14, no. 4 (April 1, 2011): 223–29. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2011.0003.

MuseumNext. “Virtual Reality Is a Big Trend in Museums, but What Are the Best Examples of Museums Using VR?,” July 31, 2021. https://www.museumnext.com/article/how-museums-are-using-virtual-reality/.

Navlakha, Meera. “How Virtual Reality Can Be Used to Treat Anxiety and PTSD.” Mashable, October 13, 2021. https://mashable.com/article/vr-treatment-anxiety-ptsd.

Portland Monthly. “Virtual Reality Curious? Venice VR Expanded Returns to the Portland Art Museum.” Accessed October 4, 2021. https://www.pdxmonthly.com/sponsored/2021/08/virtual-reality-curious-venice-vr-expanded-returns-to-the-portland-art-museum.

Potash, Jordan S., Debra Kalmanowitz, Ivy Fung, Susan A. Anand, and Gretchen M. Miller. “Art Therapy in Pandemics: Lessons for COVID-19.” Art Therapy 37, no. 2 (April 2, 2020): 105–7. https://doi.org/10.1080/07421656.2020.1754047.

Psych Central. “Why Art Therapy May Help You Manage Anxiety Symptoms,” May 28, 2021. https://psychcentral.com/anxiety/art-therapy-for-anxiety-relief.

Ramseyer, Joanne. “Harriet Claire Wadeson: Pioneer, Teacher, Colleague, and Friend.” Art Therapy 33, no. 2 (April 2, 2016): 107–10. https://doi.org/10.1080/07421656.2016.1166413.

Rezaei, Nima, Aida Vahed, Heliya Ziaei, Negin Bashari, Saina Adiban Afkham, Fatemeh Bahrami, Sara Bakhshi, et al. “Health and Art (HEART): Integrating Science and Art to Fight COVID-19.” In Coronavirus Disease - COVID-19, edited by Nima Rezaei, 1318:937–64. Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology. Cham: Springer International Publishing, 2021. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-63761-3_53.

Robb, Megan. “The History of Art Therapy at the National Institutes of Health.” Art Therapy: Journal of the American Art Therapy Association 29, no. 1 (January 2012): 33–37. https://doi.org/10.1080/07421656.2012.648097.

Roussou, Maria. “Immersive Interactive Virtual Reality in the Museum,” n.d., 8. Salmon, Felix. “Investors Pour Millions into Immersive, Interactive Art Experiences.” Axios. Accessed September 25, 2021. https://www.axios.com/investors-pour-millions-vr-experience-14602a2b-1b95-4f5f-bd4e-971bfa9a2dd4.html.

Roy, M.J. Novel Approaches to the Diagnosis and Treatment of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder: Novel Approaches to the Diagnosis and Treatment of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder. Amsterdam, NETHERLANDS, THE: IOS Press, Incorporated, 2006. http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/cm/detail.action?docID=265979.

Rubin, Peter. “The WIRED Guide to Virtual Reality.” Wired. Accessed October 15, 2021. https://www.wired.com/story/wired-guide-to-virtual-reality/.

Sciforce. “Virtual Reality in Psychology: Therapy and Research.” Sciforce (blog), October 3, 2019. https://medium.com/sciforce/virtual-reality-in-psychology-therapy-and-research-525bd9e4283a.

Shamri Zeevi, Liat. “Making Art Therapy Virtual: Integrating Virtual Reality Into Art Therapy With Adolescents.” Frontiers in Psychology 12 (February 4, 2021): 584943. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.584943.

Statista. “Sectors Disrupted by XR/AR/VR/MR Technologies 2020.” Accessed October 13, 2021. https://www.statista.com/statistics/1185060/sectors-disrupted-immersive-technology-xr-ar-vr-mr/.

SXSW. “Overcoming Obstacles: Japanese VR Dancer Yoikami’s Win At SXSW,” April 21, 2021. https://www.sxsw.com/news/2021/overcoming-obstacles-a-japanese-vr-dancers-win-at-sxsw/.

“This VR Experience Lets You Explore the International Space Station… and It’s as Amazing as It Sounds | Space.” Accessed October 13, 2021. https://www.space.com/vr-iss-experience-international-space-station.

Victoria and Albert Museum. “V&A · About Us.” Accessed October 5, 2021. https://www.vam.ac.uk/info/about-us.

Virtual Reality Art Therapy. “Virtual Reality Art Therapy.” Accessed September 23, 2021. https://www.virtualrealityarttherapy.com.

Vlake, Johan H., Jasper Van Bommel, Evert-Jan Wils, Tim I. M. Korevaar, Merel E. Hellemons, Anna F. C. Schut, Joost A. M. Labout, Lois L. H. Schreuder, Diederik Gommers, and Michel E. Van Genderen. “Effect of Intensive Care Unit-Specific Virtual Reality (ICU-VR) to Improve Psychological Well-Being and Quality of Life in COVID-19 ICU Survivors: A Study Protocol for a Multicentre, Randomized Controlled Trial.” Trials 22, no. 1 (May 5, 2021): 328. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13063-021-05271-z.

“VR+Opportunities.Pdf.” Accessed October 4, 2021. https://static1.squarespace.com/static/51d98be2e4b05a25fc200cbc/t/5919ec172994cadba4acabb3/1494871067244/VR+Opportunities.pdf.

“VR Technology in the Museums Sphere — Jasoren.” Accessed October 4, 2021. https://jasoren.com/vr-in-museums/.

“2020-AR-VR-Survey-v3.Pdf.” Accessed October 13, 2021. https://www.perkinscoie.com/images/content/2/3/231654/2020-AR-VR-Survey-v3.pdf.