This month, a giant interspecies creature will descend up New York City’s meatpacking district – at least, for those who download artist Nancy Baker Cahill’s 4th Wall app. The augmented reality (AR) piece, titled Cento is interactive and viewers are invited to collectively transform the creature by adding one of twelve feathers to the “beast,” each which reflects an intervention to save Cento and preserve planet. Cento represents species interdependence and the shared need to solve the climate crisis.

Baker Cahill is a leader in AR public art, and she considers the intersection of the two disciplines an ideal space for intervention to drive social change. Among her works, she has used space-based AR public artworks to call attention to a range of social issues, with most focusing on climate change.

Figure 1: Cento Source: Whitney Museum of American Art

“I think once you’ve experienced a powerful AR artwork in a shared immersive space with all senses engaged, it’s hard to forget. It lingers in your consciousness, like memory.”

AR’s Role IN PUBLIC ART

AR is not a new phenomenon, and as technology to create and engage with AR becomes more sophisticated, user-friendly, and affordable, it is shaping the creative landscape in a new way. As such, AR artwork is moving away from dependence on commercial or scientific success. (Young/Marshall) Artists have more freedom to create place-based artworks without costly materials or, necessarily, permission or zoning permits. As a result, artists are using AR as public art to tell stories, respond to inequity, and shift behavior for positive social impact.

The rest of this article will focus on how AR and public art is being used to tell stories for climate justice.

Augmented Reality (AR) expands the natural world with layered virtual elements. It can take a variety of forms – triggered by geographic location, some marker, or an existing artwork. It can also be entirely digital, not relying on a specific location or marker, free for the viewer to ‘place’ objects in the natural world where they please.

AR public art, like all public art, takes place outside of traditional museum settings to meet people in shared community spaces. It is designed for people to interact with it naturally in the course of their daily lives, with lower barriers for entry and participation. Overwhelmingly, AR public art relies on the viewers smartphone or personal device to access and engage with work. Currently, limited work uses a headset, projection, or other hardware (Pucihar/Kljun). AR public art allows for place-based storytelling to expand one’s understanding of an artwork and connection to an environment.

Trends in AR Public Art and Climate

Presently, there is little research at the intersection of AR, public art, and its use for climate action. To analyze potential impacts and trends in this field, the resources reviewed included artwork profiles and research on AR in public art, climate and public art, and climate and AR. Five overlapping trends emerge that can be categorized as Mimicking Natural Experience, Telling a Story, Rooted in Place,.Shareable Communication, and Interactivity.

Mimicking Natural Experience

AR public artworks are often created to “convey the experience of being in nature” (Curtis) in environments separated from the natural world.

Citing the ‘extinction of experience’ or increasing lack of hands-on natural experiences in highly urban and digital environments, people have grown desensitized to climate issues. One study shows that virtual experiences with nature can promote pro-environmental behavior, particularly if shown imagery of nature in destruction (DOI Foundation).

Source: Katie Edwards, Creative Boom.

One example of this is the piece Graphic Rewilding by Baker & Borowski, which has taken over a shopping center in London. Large native flowers line the walls of the urban, commercial space, which can be activated by a QR code to fill the viewer’s screen with moving images of “We want to inspire people to connect and empathise more with the natural world and find a healing space through these images and experiences,” the artists said about the piece (May).

Telling a Story

Powerful AR public art can tell a story and elicits an emotional reaction. It can “‘make (climate issues) real’ and provide a space for reacting with feeling.” (Curtis) As the need for public discourse on climate action increases, new ways are needed to engage people and tell nature’s stories (Frontiers).

As part of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art’s Monumental Perspectives series, artist Yassi Mazandi reflects on a story from her childhood to make a powerful statement in AR piece The Thirty Birds. During her childhood in Iran, her grandmother would tell stories of this group of 100 birds – traveling together in search of their home. When only 30 birds remained, they realized that their home was the space they shared (LACMA).

The AR piece, consisting of 30 birds emerging from a virtual is placed with a physical sculpture of Mazandi’s, featuring 100 suspended abstract bronze birds. By connecting the piece to a story in her personal identity, it creates a more impactful and memorable story. Through this story, she seeks call attention to the impacts of climate change – both on birds and humans – including loss and displacement from home.

LACMA X Snapchat | Monumental Perspectives (Collection III) | The Thirty Birds by Yassi Mazandi

Rooted in Place

Effective AR public art pieces engage with a particular place, but are often able to scale to spark conversation throughout the world. Baker Cahill stated, “In all cases, the curatorial invitation—regardless of theme—has been to pair an artwork with a location which, in the pairing, might have added resonance or value, or discursive potential outside of any traditional institutions or frameworks” (Cahill/Damiani). One example of this is by Alaskan AR conceptual artist Nathan Shafer’s, Aurora Borealis. Ability to view the aurora borealis ebbs and flows every 11 years. However, when it came time for it to be in full view in 2010, excessive light pollution in Anchorage, Alaska caused the natural light display to remain out of sight for many residents. Shafer’s work created an augmented version the spectacle available through a smartphone or personal device. Though this was specifically designed to spark conversation about light pollution in Anchorage, the piece caught wider attention and one of the piece’s first displays was in Brooklyn, New York.

I Am An Augmented Reality Creator | INDIE ALASKA

a shareable form of communication

By nature of AR public art, it is in open, public spaces and has the ability to spark conversation or allow viewers to share their experience with their online social networks. In Čopič Pucihar and Kljun’s Taxonomy for Art and Cultural Heritage (Pucihar/Kljun), communication is one of four key activities of AR in arts experiences. The corresponding literature review of museums, galleries and cultural heritage sites rated experiences across organization types the lowest at communication. The study concluded that more should be done to integrate AR work with social networks for more seamless sharing. In other cases, technical shortcomings create shared experiences in unusual ways. When Baker Cahill premiered her piece, Margin of Error in a California Desert, few viewer downloaded the required app in advance of the visit. With extremely limited access to data, participants, many strangers, gathered around the phones of people who were able to pull up the piece (Cahill/Damiani).

Source: Nancy Baker Cahill, Margin of Error (2).

Participants want to share their experience with artworks. In a case study of how AR public artwork would change how community members would engage with run down urban spaces, 16 of 21 of survey participants shared that they would be somewhat or very likely to record or share their AR experience (Young/Marshall). However – this did not calculate how many participants actually did share it.

Some AR public artwork is integrated into social media from the onset, such as the LACMA x Snapchat Monumental Perspectives series, making it easy to engage with & share content in your social networks.

Interactivity

Interactive elements of AR public art allow the artist to “make the serious fun” (Curtis). It also enhances learning and information retention about an artwork or idea.

In a Singapore University of Technology and Design study, participants were asked to participate in a climate-focused augmented reality game called PEAR and knowledge and awareness about sustainability were measured both before and after. In the mobile-based game, participants follow a ‘Personalized Environmental Assistance Robot’ as it completes various tasks to avoid environmental catastrophe. Participants demonstrated higher levels of knowledge and more positive behavioral scores after participating in the game (Wang, et al.).

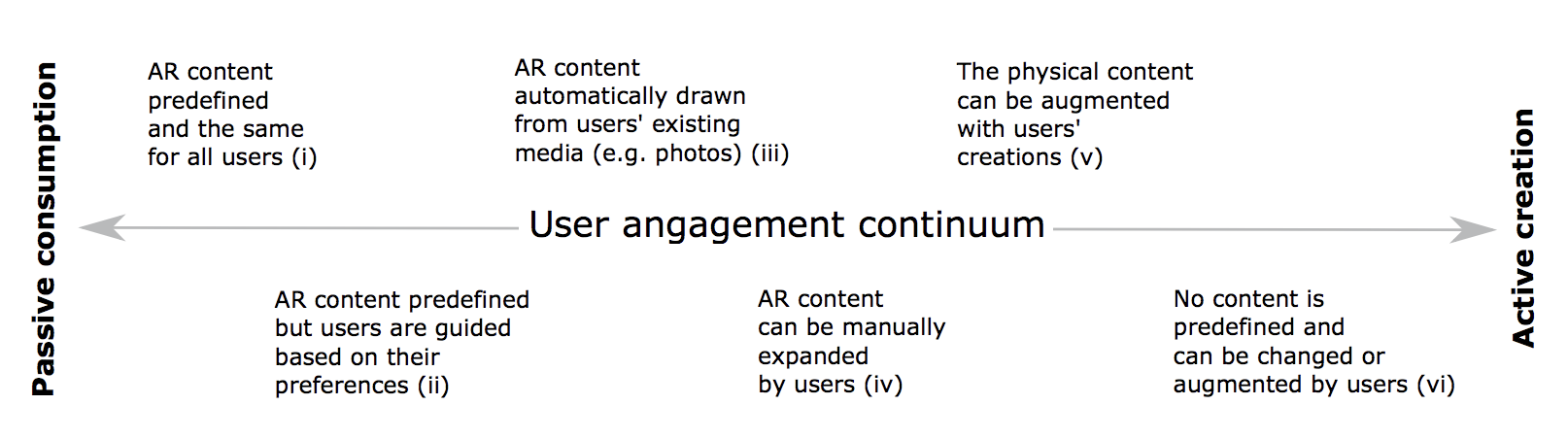

AR public art can allow viewers to move out of passive consumption and into active creation and participation with the work. Different applications of AR in public art fall across a user engagement continuum (Pucihar/Kljun), ranging from entirely pre-defined content to content entirely created or changed by users.

Figure 2. User Engagement Continuum” Source: Kljun, M., Coulton, P., Čopič Pucihar, K. (2022). User Engagement Continuum: From Art Exploration to Remixing Culture with Augmented Reality.

Returning to the opening example, Baker Cahill’s Cento is an example of interactive AR public art for climate intervention. Users are invited to interact with the piece by selecting a preferred feather and adding it to the creature where they please. Once added, it changes Cento for all who view the piece, anywhere in the world.

CONCLUSION

Augmented Reality will likely not go away anytime soon. As technology develops, along with access tools for creators, we will see more artwork reacting and pushing for action on current social and environmental issues.

As AR public art experiences continue to develop, we may see a push for more engaging user-generated content, with increased utility for sharing within your social network. This will also likely come with increased regulation around where artists can create augmented art and what is considered appropriate.

Continued consideration is needed to better understand how people engage with AR public artwork and evaluate its effectiveness in shifting pro-environmental behavior.

-

Angeleti, Gabriella. “Chimeric creature descends on the Whitney Museum in new augmented reality commission.” The Art Newspaper. Sept. 25, 2023. https://www.theartnewspaper.com/2023/09/25/a-chimeric-creature-descends-on-new-yorks-meatpacking-district

Cahill, N.B., Damiani, J. (2022). Augmented Reality Interventions in Shared Space: Subversion and Social Impact. In: Geroimenko, V. (eds) Augmented Reality Art. Springer Series on Cultural Computing. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-96863-2_11

Čopič Pucihar, K., Kljun, M. (2022). “ART for Art Revisited: Analysing Technology Adoption Through AR Taxonomy for Art and Cultural Heritage.” In: Geroimenko, V. (eds) Augmented Reality Art. Springer Series on Cultural Computing. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-96863-2_1

Garzón, J., Ceballos, S., Ocampo, E., Correa, M. (2023). “Augmented Reality-Based Application to Explore Street Art: Development and Implementation.” In: De Paolis, L.T., Arpaia, P., Sacco, M. (eds) Extended Reality. XR Salento 2023. Lecture Notes in Computer Science, vol 14219. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-43404-4_12

“I Am An Augmented Reality Creator.” Indie Alaska. PBS Digital Studios. December 4, 2019. https://www.pbs.org/video/i-am-an-augmented-reality-creator-indie-alaska-ittaiq/

Kljun, M., Coulton, P., Čopič Pucihar, K. (2022). User Engagement Continuum: From Art Exploration to Remixing Culture with Augmented Reality. In: Geroimenko, V. (eds) Augmented Reality Art. Springer Series on Cultural Computing. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-96863-2_18

Klein, Sina A., and Benjamin E. Hilbig. “How Virtual Nature Experiences Can Promote Pro-Environmental Behavior.” Journal of Environmental Psychology 60 (December 1, 2018): 41–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2018.10.001.

“LACMA × Snapchat: Monumental Perspectives (Collection III) | The Thirty Birds by Yassi Mazandi.” Los Angeles County Museum of Art. Youtube. September 6, 2023. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=15XayuGSG-A

“LACMA x Snapchat: Monumental Perspectives” Los Angeles County Museum of Art. Accessed October 4, 2023. https://www.lacma.org/art/exhibition/lacma-snapchat-monumental-perspectives

May, Tommy. “Artists use AR to ‘rewild’ a London shopping centre.” Creative Boom. June 15, 2023. https://www.creativeboom.com/news/graphic-rewilding/

Miller, Cecily. “Can Art Save the World? A Look at Public Art Projects in the USA that seek to promote Environmental Stewardship.” David Curtis, Editor. 2020. Using the Visual and Performing Arts to Encourage Pro-Environmental Behaviour. Newcastle upon Tyne, UK: Cambridge Scholars Publishing. https://search-ebscohost-com.cmu.idm.oclc.org/login.aspx?direct=true&db=nlebk&AN=2648160&site=ehost-live&scope=site.

Reis, Cristina M., and António Câmara. “Expanding Nature’s Storytelling: Extended Reality and Debiasing Strategies for an Eco-Agency.” Frontiers in Psychology 14 (2023). https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2023.941373.

Skwarek, M. (2018). Augmented Reality Activism. In: Geroimenko, V. (eds) Augmented Reality Art. Springer Series on Cultural Computing. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-69932-5_1

Wang, Kyra, Zeynep Duygu Tekler, Lynette Cheah, Dorien Herremans, and Lucienne Blessing. 2021. “Evaluating the Effectiveness of an Augmented Reality Game Promoting Environmental Action” Sustainability 13, no. 24: 13912. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132413912

Young, Tamlyn, and Mark T. Marshall. 2023. “An Investigation of the Use of Augmented Reality in Public Art” Multimodal Technologies and Interaction 7, no. 9: 89. https://doi.org/10.3390/mti7090089