digital stewardship of physical objects

Writing on the promises and potentials of digital culture in 2009, Alfredo M. Ronchi said, “If this technology is to be harnessed to enhance democratic principles, it must contribute to the creation and enrichment of an educated, informed citizenry; it must incorporate the accumulated knowledge and creativity of the past, and it must anticipate and enhance creativity for the future.” It is worth considering in 2022 whether museums have fulfilled much of the democratic promise of digital technology as an aid to providing cultural knowledge to the public.

The International Council of Museums re-defined the museum in 2022 as:

“a not-for-profit, permanent institution in the service of society that researches, collects, conserves, interprets and exhibits tangible and intangible heritage. Open to the public, accessible and inclusive, museums foster diversity and sustainability. They operate and communicate ethically, professionally and with the participation of communities, offering varied experiences for education, enjoyment, reflection and knowledge sharing.”

ICOM’s new definition encompasses much of the democratizing potential of digital culture that Ronchi discussed in 2009. Offering online experiences that aim to serve the mission of a museum is a crucial current step for museums to remain relevant, respected, and appreciated in their service to the public.

The dialogue surrounding the possibilities for digital museum engagement has been prominent since the 1990s. However, digital museum offerings continue to be discussed primarily as an aid or appendage to the physical museum experience. There is a gap in discussions surrounding digital museum experiences as stand-alone offerings to the public. As society shifts to an enhanced and more personal relationship with digital culture, museums mistakenly attempt to replicate the physical digitally. Thus, there is a limited discourse on the potential value of such experiences to audiences, artists, and museums. The Covid-19 pandemic changed the public’s relationship with the digital realm, further blurring the line between our digital and physical lives.

Digital storytelling as strategy

As museums consider their value and responsibility to the public, they have … “begun to focus on the visitor experience as a process that is not limited to the time spent in the museum itself.” (Patrelli et al., 2016) We consider meaning-making from the first point of contact with the museum (which is primarily a digital contact point) all the way to visitors' reflections on the experiences long after their physical visits. Rather than thinking about it in the traditional trajectory of ‘contact made—visiting information gathered—-physical visit—-reflection’, what if: we thought about the opportunities we could extend to visitors in terms of engagement at that initial point of contact?

How could they engage?

How could it stand on its own in a way that honors the art and artists, and inspires thought, emotion, and reflection?

How could museums honor objects in their specific context online, rather than attempting to replicate the experience of those objects in the physical, material realm?

Should the audiences choose to visit in person after this experience, how might it condition their physical and emotional journey through the space?

We might also begin to consider how storytelling functions in the digital realm. Museums are sites of stories. Ask any curator what story they are trying to tell with an exhibition and they will have an answer. Do the online offerings tell a cohesive human story? They certainly have the potential to.

One study found that “Digital empathic stories [in the museum context] can evoke narrative transportation, and in some cases, personal attachment and critical (self)-reflection.” (Perry et al., 2019.) Rather than offering art in a vacuum online, it is worth considering how museums can weave digital narratives with the wealth of visual and textual information they have about their collections. Contemporary art in particular may have an exceptionally valuable capability of doing so. Han and Raffee mention, “Since its inception, contemporary art has been unable to be imprisoned by book knowledge…its concept and creative practice can be extended and transformed in natural labs such as art museums, workshops, and mobile apps.” The same study found that art students making digital engagement with contemporary art a daily, routine activity greatly benefitted their learning process.

In order to discuss the potential digital futures for contemporary art museums, this article will first give an overview of the digital foundations that contextualize museums’ current digital ecosystem.

The Current Digital Media Climate

Audiences are increasingly looking for digital arts and entertainment experiences. The NEA’s 2017 Survey of Public Participation in the Arts noted that 74% of respondents (175 million adults), used electronic media to consume artistic or arts-related content.

Further 2017 research revealed what was compelling to audiences about digital versus physical arts and culture activities:

Fig 1: Image via author, data from Culture Track 2017 Report

During the pandemic, livestreams, podcasts, and online classes/workshops were the top three digital experiences attended by arts audiences. Interest in the content and being reasonably priced were the two main motivations for individuals who attended such activities. While 65% reported they expected to prefer in-person activities once arts institutions opened back up, 35% mentioned they would either have no preference between online and in-person or that they would actually prefer online entirely.

The 35% that museums can expect to engage with their digital offerings is a significant portion of museum audiences and one that should not be overlooked.

According to Culture Track’s Wave 2 Report, when it comes to arts engagement and Covid-19, arts participation was most notable online in the case of individual performers. The second largest digital attendance was to museums, at only 20%. Museum digital attendance was double that of theater digital attendance (10%) and almost three times that of Dance (7%).

““Without some degree of digital interactivity, it is challenging for a museum to remain interesting and relevant to a young tech-savvy audience.” ”

The demand for digital experiences is ever-rising. The question moving forward is how museums can provide such digital interactivity in a way that honors the art that museums steward.

Museum Digital Offerings: Where do they stand?

Museums began investigating opportunities for digital presences in the 1990s when the world wide web opened to the public. At the outset of this, the fear of digital experiences de-prioritizing physical visits to the museum was prominent. While this fear has largely been dispelled, it resurfaces from time to time as more immersive technologies are developed. During Covid-19 lockdowns, museums scrambled to provide online experiences to visitors while their physical doors were closed. As Hoffman remarked, “Temporarily, the virtual replaced the actual.” (Hoffman, 2020). Most of these virtual interventions have remained as features on museum websites. However, the readiness of museums to offer educational, interactive, and creative experiences online was highlighted as a weakness during the pandemic. Compared to other experiences in the online realm, such as social media and especially video streaming services, museums were behind in their digital entertainment offerings.

As many museums rushed to provide online content during the Covid-19 pandemic, patterns emerged surrounding the decisions of what, where, and how their collections would be stored and accessed online. Museums almost exclusively utilized their already-established websites (as well as their social media platforms) as the contact point for these digital offerings.

360 tours, collections archives, online education guides and workshops, and lectures from curators and artists emerged as common offerings to the public. Larger, better-funded museums had a very distinct advantage in terms of the quality of digital content provided. Each of the primary offerings museums adapted to online exemplifies “a product of museums’ long history of poorly articulating what ‘digitization’ means and viewing online potentiality through the lens of our physical world.” (Hoffman.) 360 Tours and other virtual tour methods are prime examples of how museums attempted to replicate the physical experience online.

An example of a 3D contemporary art tour from the Cranbrook Art Museum

The above example from the Cranbrook is typical of 360 tours across all sizes of museums. Consistently, the pieces, zoomed in, are not high image resolution and it is difficult to discern minute details of the pieces. The general scope of such 360 tours seems to function just to convey the layout and general “feel” of the space of the gallery itself, rather than being concerned with the individual objects that fill it.

Conversely, Google Arts and Culture has recently been adding more unique layers to experiencing physical objects online. Many of their recent offerings in the “explore” function demonstrate how the web can offer unique advantages in terms of animating, reimagining, and adding layers to the story of an object.

Google Arts and Culture in Collaboration with Royal Museums of Fine Art Belgium

Despite this video being considered a Virtual Reality experience, it holds up on its own without a VR headset. It re-imagines the piece within a new contextual route of experience.

Full Monet “Water Lily Pond” painting, not zoomed.

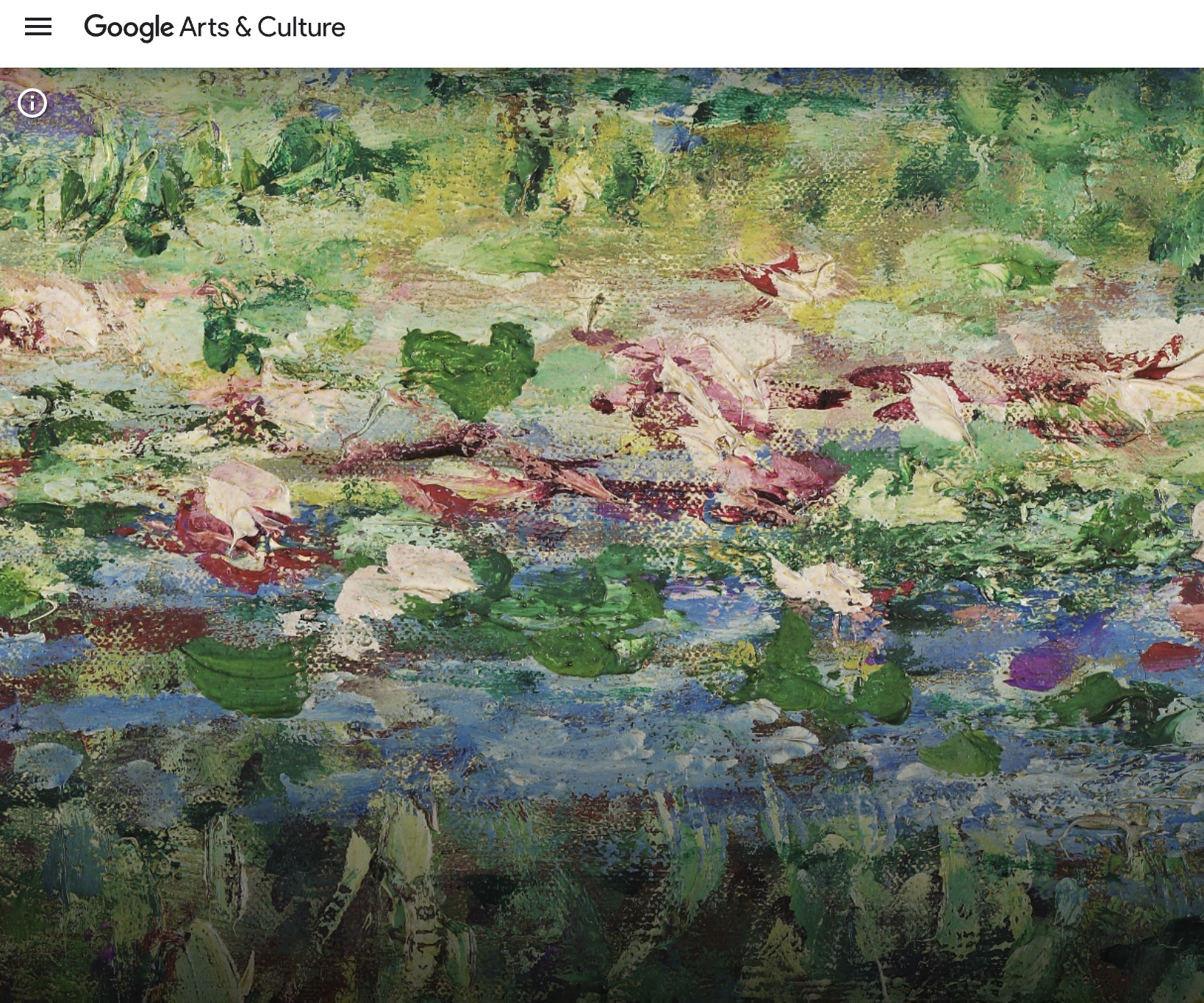

The detail and photo quality of Google Arts and Culture “Art Up Close: Zoom Into Claude Monet”

Another obvious technological aspect of exploration on Google Arts & Culture is the general zoom and image quality of the works. In particular, their “Art Up Close” feature is promising in terms of being able to take in aspects of a work like brush stroke and minute details, from home.

Of course, Google Arts and Culture has access to funding that individual museums often don’t have. However, I utilize these digital offerings to show an example of what types of experiences museums might start aiming for as their digital budgets grow.

The role of place

Much research has been done on the idea of “place-bound determinants of behavior” within the physical context of museums. How individuals move through the museum, where they stop, what they do, and the feelings that accompany that movement have been objects of discussion for decades. When we consider the social meaning that spaces embody as the public experiences them, we can extend these questions to the digital realm. What kind of experience of digital movement do visitors have navigating a museum’s website?

Despite work being done in the realm of UX design and human-centered design for museum websites, there is a lack of discussion surrounding specifically the user experience of online art contact points. Most of the 360 tours analyzed did not allow high-quality resolution of the images on the walls, but rather gave the visitor a surface-level feeling of the inside of the museum architecturally and spatially. In terms of experiencing the art itself in exhibitions, the videos of exhibition walk-throughs with curators that include close-ups of the works were much more effective.

Still, contemporary art museums are limiting their own potential for audience digital engagement by only mimicking the physical experience. It seems that artists and audiences, faster than museums, understand that, “Art as experience, as distinct from art as artefact or object, is steadily making inroads into public consciousness and, quietly as yet, influencing the norms of the wider art world.” (Candy and Ferguson, 2014) However, contemporary art museums maintain the notion of art as pure object throughout their digital presences, and when interactivity is attempted, it is only attempted in conjunction with physical interactivity–ie moving through the space.

Analyzing Contemporary Art Museum Offerings in 2022

In order to get a picture of the current landscape of contemporary art museums and their digital offerings, the author used the catalog of ModCo museums. The Modern and Contemporary Reciprocal Program (Modco) is a cohort of 75 modern and contemporary art museums that have a reciprocal membership program. ModCo museums were used as the sample for the purpose of this research because of the convenience of a singular list of museums that could be easily exported to a spreadsheet and analyzed. 10 museums were taken out of the sample due to being in Canada and/or the content not being applicable.

Analysis of 65 American contemporary art museums’ digital offerings revealed distinct patterns of decision-making across the board and illuminates where the gaps currently exist. This analysis groups these museums into three categories: Small, Mid-size, and Large.

Small museums were those whose budgets fell under 1 million. Mid-size are those with budgets between 1 and 10 million, and large are those with budgets over 10 million dollars.

Note that, for the purposes of this research, “Online Archives” are defined as searchable collections that include high-resolution images of the works, as well as detailed information. Additionally, “virtual exhibition walk-throughs” are defined as photo-based demonstrations of exhibitions that are not 360 tours, but show each piece in high resolution, and include wall text and exhibition curatorial descriptions. The categories of virtual offerings were chosen as the most prominent features across the board.

It is worth noting that, when looking at the totals, there is no virtual offering that more than 50% of the contemporary art museums examined offer.

The most common offering across the board is a digital archive of collections, which was a feature of 49% (32) of the 65 museums analyzed. The quality and accessibility of digital archives varied greatly, often correlated to museum size (and therefore budget size). Large museums had digital archives on their websites at a rate of 88.8%, strikingly disparate to small museums, of which only 27.8% had digital archives. None of the small museums evaluated had a mobile app, whereas almost a third of large museums did.

Contrasting the frequency of these offerings with the preferred digital arts experiences discussed previously (livestreams, podcasts, and online classes/workshops), there appears to be a gap between what museums offer and what audiences enjoy.

Limitations of Current Museum Website Infrastructure

Aside from the actual content that is offered, access to that content is an important component of analysis. A consistent issue with these digital offerings was actually finding them on the website. In an attempt to illustrate the ease of finding these offerings, the number of clicks to reach them was also analyzed. On average, across all sizes of museums, it took 3.8 clicks to reach a distinct digital offering in any of the categories. Large museums had the highest rate of clicks at 4.1. These clicks do not account for searching to find the offerings but are the number of clicks it takes if the user already knows exactly where to find them.

Figure 3 Source: Author

It is also worth noting that the average number of clicks does not account for scrolling, and many navigation links were buried toward the bottom of a page scroll.

Figure 4: Author Recording of DIA website

This recording shows the author looking for all of Dia’s digital offerings on their website. It demonstrates just one example of how various digital offerings are buried within separate parts of a museum website—the online collection, video section, and other digital components are in very distinct parts of the website.

Museum websites are singular destinations for wide and varied types of information. They include information on how to get to the museum, accessibility, museum history, mission, events and programs, and much more. Attempting to provide easily accessible digital art experiences within the context of all of this information is difficult. Hoffman mentions, “Not only do online exhibitions become frustratingly entangled with everything else on a museum’s website, but much of the distinction lent by interpretation of objects is obscured by predetermined image, text, and video formats.” Whereas in a physical museum, most users know where different types of information are typically encountered (organizational information at the front desk, curatorial/artist information in the galleries, object descriptions next to the objects, etc), all of these sites of knowledge are blurred into a singular space within the museum website.

Where are we headed?

“Online exhibitions offer the opportunity to do more–offer deeper, different, or competing interpretations; avenues to explore further; chances to look and think in ways not conducive to a linear gallery setting.”

It is time for contemporary art museums to question the motivations behind their digital offerings critically, as well as consider why and how they want people to access the art that they steward digitally. It may not be productive to attempt to situate digital art engagement within the context of the rest of the museum website, but rather employ a distinct digital portal that is designed specifically for arts engagement. Place-based inquiry into the digital enjoyment of art may be a beneficial route to considering such implementations. New contexts, possibilities, and benefits will emerge as we continue to develop strategies surrounding digital offerings in their own context, rather as appendages to the physical.

Next Stages of Research (Part Two)

This research will continue with the investigation of the possibilities of these site-specific digital contact points. By engaging with professionals in the field as well as including case studies on cutting-edge and creative ways of interacting with art online, this research will provide a lens to the creative possibilities of digital futures for contemporary art museums. This research will also continue to explore the barriers to the success of such projects such as tech infrastructure and budget constraints and attempt to address some preliminary solutions to such barriers. Finally, the next iteration of this research will engage in user experience analysis of current digital offerings and attempt to reveal more concrete patterns of audience preferences.

-

Auxier, Brooke, and Monica Anderson. “Social Media Use in 2021.” Pew Research Center: Internet, Science & Tech (blog), April 7, 2021. https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/2021/04/07/social-media-use-in-2021/.

Candy, Linda, and Sam Ferguson. Interactive Experience in the Digital Age: Evaluating New Art Practice. Springer Series on Cultural Computing. Heidelberg ; Springer, 2014.

Cesário, Vanessa, António Coelho, and Valentina Nisi. “‘This Is Nice but That Is Childish’: Teenagers Evaluate Museum-Based Digital Experiences Developed by Cultural Heritage Professionals,” 159–69. CHI PLAY ’19 Extended Abstracts. ACM, 2019. https://doi.org/10.1145/3341215.3354643.

“Coronavirus Research Series 4: Media Consumption and Sport.” Global Web Index, April 2020. https://www.gwi.com/hubfs/1.%20Coronavirus%20Research%20PDFs/GWI%20coronavirus%20findings%20April%202020%20-%20Media%20Consumption%20(Release%204).pdf.

Culture Track. “Culture + Community in a Time of Transformation: A Special Edition of Culture Track,” November 3, 2021. https://culturetrack.com/research/transformation/.

“Culture Track 2017 Study.” La Placa Cohen. Accessed September 28, 2022. https://2017study.culturetrack.com/.

Han, Yupei, and Mohd Rafee Yakup. “The Practical Effect and Positive Influence of Mobile Art Apps in Online Education for Contemporary Art.” International Journal of Academic Research in Progressive Education and Development 11, no. 2 (2022). https://doi.org/10.6007/IJARPED/v11-i2/13026.

Hoffman, Sheila K. “Online Exhibitions during the COVID-19 Pandemic.” Museum Worlds 8, no. 1 (2020): 210–15. https://doi.org/10.3167/armw.2020.080115.

International Council of Museums. “ICOM Approves a New Museum Definition.” Accessed October 13, 2022. https://icom.museum/en/news/icom-approves-a-new-museum-definition/.

“Key Findings From Wave 2, Culture Track.” LaPlaca Cohen, November 23, 2021. https://s28475.pcdn.co/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/CCTT-Key-Findings-from-Wave-2.pdf.

Meyrowitz, Joshua. No Sense of Place: The Impact of Electronic Media on Social Behavior. New York, [New York] ; Oxford University Press, 1985.

Perry, Sara Elizabeth, Maria Roussou, Sophia Mirashrafi, Akrivi Katifori, and Sierra McKinney. “Shared Digital Experiences Supporting Collaborative Meaning-Making at Heritage Sites.” In Shared Digital Experiences Supporting Collaborative Meaning-Making at Heritage Sites. Routledge, 2019. http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/133026.

Petrelli, Daniela, Mark T. Marshall, Sinéad O’Brien, Patrick McEntaggart, and Ian Gwilt. “Tangible Data Souvenirs as a Bridge between a Physical Museum Visit and Online Digital Experience.” Personal and Ubiquitous Computing 21, no. 2 (2016): 281–95. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00779-016-0993-x.

Ronchi, Alfredo M. ECulture Cultural Content in the Digital Age. 1st ed. 2009. Berlin ; Springer, 2008. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-540-75276-9.