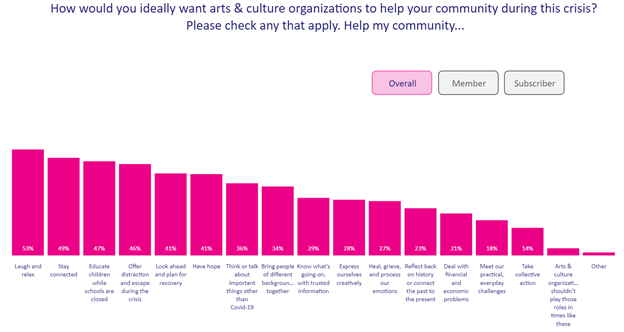

Arts organizations play important roles in their communities beyond providing access to art itself. Arts organizations are also valued venues for human connection. In LaPlaca Cohen’s Culture Track 2017, 68% of respondents indicated “interacting with others” as a draw for cultural participation, and about half of respondents in LaPlaca Cohen’s 2020 study, Culture and Community in a Time of Crisis, revealed desires for cultural organizations to help communities “stay connected” during this time (Figure 1). These data points demonstrate that audiences look to arts organizations to not only foster connections through art, but also nurture communities beyond the art.

Figure 1: Role of cultural organizations during pandemic crisis. Source: Culture Track.

In the past, in order to better serve patrons and communities at large, some arts organizations, such as Signature Theatre in New York (Figure 2), have transformed their buildings’ public areas into “third places”—spaces that are not just glorified vestibules between the art and the outside world, but spaces where people can also stay, connect, unwind, and engage. With the closing of lobbies and shifts to digital content in the spring of 2020, arts organizations may have temporarily lost the power to bring people together in a physical building, but, through digital programming, they have also gained access to a whole new audience for whom those physical spaces may have posed any number of barriers. When facilities and their lobbies reopen, or even before they do, how might arts organizations continue to serve communities who want to engage from a distance by designing virtual third places that make way for the connection and community people crave from the arts?

Figure 2: Signature Theatre Lobby in New York, NY. Source: Jill Slater for OpenCity Projects

Figure 3: Description of Third Place. Source: Jonelle Seitz for Personify Blog.

What is a Third Place?

Long before our world was overtaken by a global pandemic, sociologist Ray Oldenburg expressed concern that increasingly suburban societies were contributing to social isolation. Without easily accessible community gathering spaces such as coffee shops, diners, and barber shops, he argued, communities could lose their portals for entry, conversation, and unification (Oldenburg,1997). In his 1989 book The Great Good Place, Oldenburg calls these community gathering places—these social spaces outside of work or home—“third places” (Oldenburg,1989). Based on Oldenburg’s theory, city planners have long incorporated third places into their plans to promote socialization and vitality within communities, and, as mentioned previously, arts organizations have also redesigned their lobbies with similar goals in mind. However, no matter the setting, third places are recognized by the quality of the environment they create. Third places are:

natural social levelers that invite people to connect across lines of social or economic difference

widely accessible homes away from home where visitors can escape family or work-related roles

spaces that invite casual, chance conversations over common interests or experiences

For any space to function as a true third place, all of these conditions must be present.

Figure 4: “My Third Place” by Chrysler Museum of Art. Source: YouTube.

Meeting Third Place Criteria in the Virtual World

Unsurprisingly, as human interactions have moved increasingly online, some have questioned whether online communities can meet the criteria (and need) for third places. In recent years, Oldenburg has maintained that third places are specifically “face-to-face phenomena” because in real third places, you organically “open yourself up to whoever is there.” Thus, social media feeds, which are aggregates of asynchronous interactions rather than platforms for chance, real-time proximity to others, are not third places. However, full virtual worlds such as Nintendo’s 2020 part-game-part-virtual-escape Animal Crossing, where players can cross paths with each other, make friends, and even visit each other’s “islands,” are much closer to the coffee shops and spontaneous camaraderies that Oldenburg originally envisioned. Interestingly, Animal Crossing players can even take their “friends” to a virtual art museum (Figure 5). Certainly, many of the functions and outcomes of vibrant third places can be created by online platforms.

Figure 5: Friends in Animal Crossing visit an art museum. Source: The Iris: Behind The Scenes at the Getty.

Still, to fully meet Oldenburg’s criteria (and create utility for arts organizations wanting to foster virtual third place environments), in addition to providing an environment for spontaneous, real-time interaction, any virtual third place must also center conversation as a primary activity, not just a likely byproduct. The virtual event platform High Fidelity is trying to do just that by allowing up to 150 guests to “walk” through a virtual room and experience different groups and conversations, just like they might at a party—or maybe a pre-show lobby. Outside of planned events, platforms like Clubhouse, where users can spontaneously jump into conversation “rooms” at any point throughout the day, or VRchat, where user-created avatars can meet and engage in a VR world, keep spontaneous social interaction at the core. Interestingly, some research, such as that by technology and communications expert Charles Soukup, suggests that the freedom to engage through anonymity or “alternative personae” in virtual spaces creates “less inhibited” and especially “spirited and lively” conversations (Soukup, 2006). In other words, despite the clear differences and limitations of virtual worlds, virtual platforms may also have some advantages over physical settings for conversation generation.

Figure 6: “Host Your Event in High Fidelity” by High Fidelity. Source: YouTube.

The Opportunity for the Arts

While arts organizations may not be ready to build entire VR-based worlds for their patrons, arts administrators might consider how to adapt platforms like High Fidelity or others forthcoming to help reproduce some if not all of the socially-leveling, conversation-focused environments they have worked to cultivate in their physical spaces. However, just like building a bar into a theatre lobby doesn’t automatically create a third place, simply enabling a live chat alongside a digital concert doesn’t constitute a “virtual” third place, either. Whether physical or virtual, third places must be thoughtfully cultivated to be effective.

For many community members, no virtual option will replace face-to-face interactions; at the same time, given that Zoom alone experienced a 354% increase in users during the first half of 2020, people may be more willing than ever this year to try or rely on new tools for human connection. Additionally, for the more than half of U.S. residents who have participated in digital cultural activities in 2020, providing community engagement opportunities online could create more satisfying arts experiences (as suggested by Culture Track ’17) and strengthen relationships between arts organizations and their communities. Finally, given the large number of digital cultural participators who are new to the content or the organizations, virtual third places may help new digital patrons feel more welcomed and connected to arts communities near and far, regardless of when or if they ever plan to walk through an organization’s physical doors.

Resources

Budds, Diana. “It’s Time to Take Back Third Places.” Curbed, May 31, 2018.

https://archive.curbed.com/2018/5/31/17414768/starbucks-third-place-bathroom-public.

Butler, Stuart M., and Carmen Diaz. “‘Third Places’ as Community Builders.” Brookings Institute, September

14, 2016. https://www.brookings.edu/blog/up-front/2016/09/14/third-places-as-community-builders/.

Chang-Yi Zawacki, Selina, and Sarah Waldorf. “How to Build an Art Museum in Animal Crossing.” The Iris:

Behind the Scenes at the Getty (blog), April 16, 2020. https://blogs.getty.edu/iris/how-to-build-an-art-

museum-in-animal-crossing/.

Constine, Josh. “Clubhouse Voice Chat Leads a Wave of Spontaneous Social Apps.” TechCrunch, April 18, 2020. https://techcrunch.com/2020/04/18/clubhouse-app-chat-rooms/.

Signature Theatre. “Directions, Accessibility and Resources at Signature Theatre.” Accessed September 26, 2020. https://www.signaturetheatre.org/Visit.aspx.

Fagan, Kaylee. “VRChat: What It’s like Using the Online Meeting Place of the 21st Century - Business Insider.” Business Insider, March 1, 2018. https://www.businessinsider.com/vrchat-explained-2018-2#in-this-world-the-limits-of-physics-logic-and-science-are-no-match-for-the-human-imagination-which-runs-rampant-with-little-regard-for-consequences-3.

Hayden, Scott. “‘High Fidelity’ Shifts Focus Towards Non-VR Due to Slow Growth – Road to VR.” RoadTOVR, April 17, 2019. https://www.roadtovr.com/high-fidelity-shifts-focus-towards-non-vr-due-slow-growth/.

High Fidelity. “Host Your Event in High Fidelity.” YouTube, July 2, 2020. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8n-wbjex8ak.

The Verge, June 2, 2020. https://www.theverge.com/2020/6/2/21277006/zoom-q1-2021-earnings-coronavirus-pandemic-work-from-home.

LaPlaca Cohen. “CCTC Interactive Tool.” Culture Track, 2020. https://culturetrack.com/cctc-interactive-tool/.

LaPlaca Cohen. “Culture Track ’17.” Culture Track, 2017. https://2017study.culturetrack.com/.

Low, Setha. “How Cafes, Bars, Gyms, Barbershops and Other ‘third Places’ Create Our Social Fabric.” The Conversation, May 1, 2020. https://theconversation.com/how-cafes-bars-gyms-barbershops-and-other-third-places-create-our-social-fabric-135530.

Oldenburg, Ray. “Our Vanishing ‘Third Places.’” Planning Commissioners Journal Number 25, no. Winter 1996-1997 (1997).

Oldenburg, Ray. The Great Good Place: Cafes, Coffee Shops, Bookstores, Bars, Hair Salons, and Other Hangouts at the Heart of a Community. Da Capo Press, 1989.

High Fidelity. “Online Audio Spaces for Groups and Crowds High Fidelity.” Accessed October 19, 2020. https://www.highfidelity.com.

Russell, Anna. “Zoom Fatigue and the New Ways to Party.” The New Yorker, September 17, 2020. https://www.newyorker.com/culture/culture-desk/zoom-fatigue-and-the-new-ways-to-party.

Seitz, Jonelle. “For a Vibrantly Engaged Community, Look to Third Place Theory.” Personify (blog), August 16, 2018. https://personifycorp.com/blog/for-a-vibrantly-engaged-community-look-to-third-place-theory.

Slater, Jill. “Frank Gehry’s Indoor Public Space for the Signature Theater.” Opencity Projects (blog). Accessed October 16, 2020. http://opencityprojects.com/indoor-frank-gehry-creates-public-open-space-for-the-signature-theater/.

Soukup, Charles. “Computer-Mediated Communication as a Virtual Third Place: Building Oldenburg’s Great Good Places on the World Wide Web.” New Media & Society 8, no. 3 (June 2006): 421–40. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444806061953.

“Taking Note: Revisiting Baseline Assumptions about Arts Engagement.” Accessed October 20, 2020. https://www.arts.gov/stories/blog/2020/taking-note-revisiting-baseline-assumptions-about-arts-engagement.

“Third Places in Culture - Ray Oldenburg Q&A.” Steelcase. Accessed September 24, 2020. https://www.steelcase.com/research/articles/topics/design-q-a/q-ray-oldenburg/.

Webb, Kevin. “‘Animal Crossing: New Horizons’ for the Switch: What We Know so Far.” Business Insider, June 13, 2019. https://www.businessinsider.com/animal-crossing-new-horizons-nintendo-switch-release-date-2019-6#up-to-eight-player-characters-can-live-on-the-same-island-and-four-people-can-play-new-horizons-at-once-using-the-same-switch-if-youre-playing-online-you-can-have-eight-players-exploring-the-same-island-at-once-2