Has the fast moving pace of technology left your institution feeling threatened? If your answer is yes, know that you are not alone. A widely held belief in the industry is that the convenience of streaming platforms, such as Netflix and Hulu, are discouraging the public from attending live performances. As broadcasts of live performances become more popular in the US and across the world, understanding the true impact of their disruption is need-to-know information for every arts manager.

Fortunately, several organizations in the UK have teamed up to study the impact that cinema and live broadcasts have on theater. Their findings paint a brighter picture for the future of live performing arts.

Researchers from the King’s College London and the University of Brighton completed a study funded by Arts Council England that discovered attending the cinema likely serves as a gateway to attending live performances. Their research studied live cinema attendees and gaged their interest in attending the performing arts. Out of their respondents:

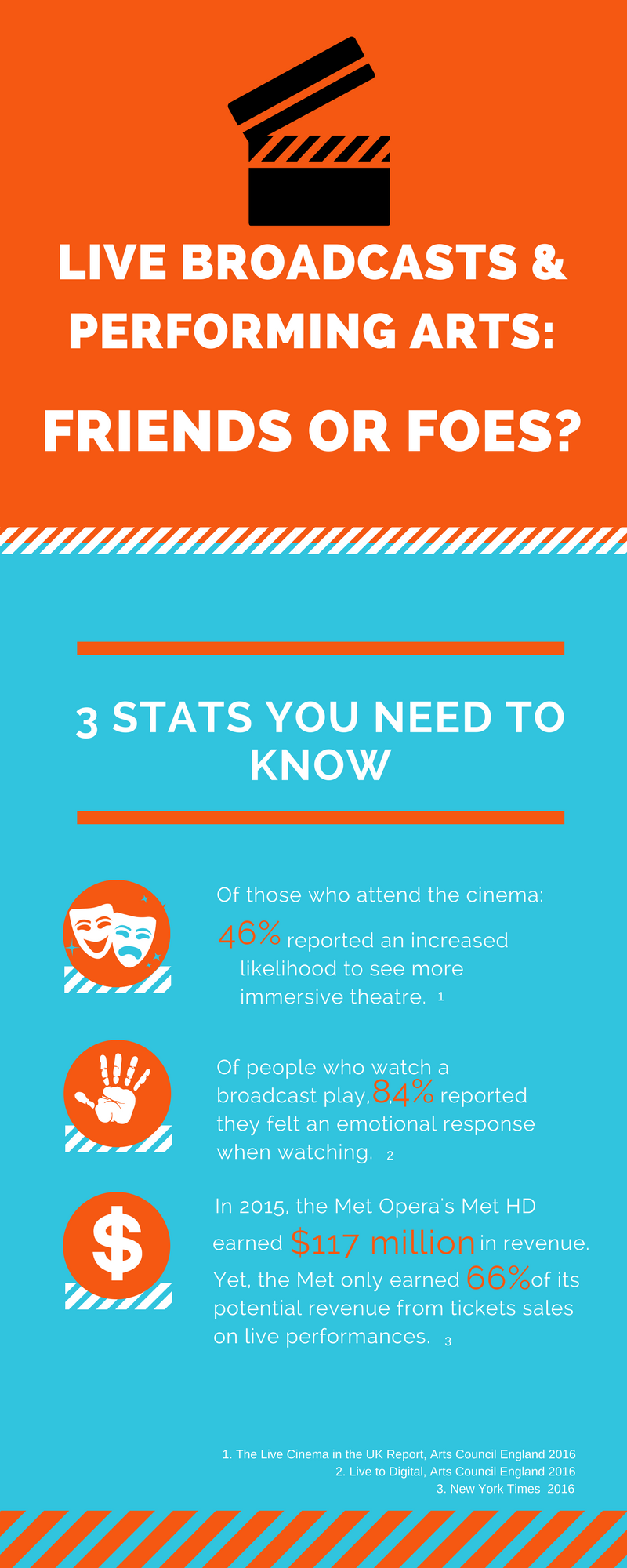

- 46% reported an increased likelihood to see more immersive theatre

- 31% reported an increased likelihood to attend classical music events

- 27% reported an increased likelihood to attend dance performances

This report provides vital information to arts managers because it indicates an opportunity to convert cinema attendees into live performing arts attendees. By targeting advertisements to this group, marketing departments may be able to capture low hanging fruit.

However, these statistics refer to film and therefore do not take into consideration the effect live broadcasts and streaming have on the performing arts, an increasingly growing medium that could present a threat to performing arts organizations who so heavily rely on in person attendance.

A study was conducted by a team comprised of Arts Council England, UK Theatre, the Society of London Theatre, and AEA Consulting to assess the relationship between theater and live broadcasts. Their study measured opinions and personal experiences of individuals watching broadcast screenings of plays, concluding that broadcasts had a minimal impact on live performance. For the study, broadcasts can be understood as stage productions filmed during live performances that were edited to be presented as video. Broadcasts are commonly viewed in public spaces such as baseball parks and movie theaters or at home over the internet.

Their research found that when people watched a broadcast of a play, 84% of people felt an emotional response while watching. 88% of people who had seen a cinema broadcast said they would recommend them to other people.

These statistics and the idea that broadcasts can resonate with audiences on an emotional level might make some arts managers uneasy. However, only 33% of the audiences reported that watching the broadcast was more engaging than seeing a live performance and only 38% of the respondents claimed live-to-digital (theatre) was a positive experience overall. Taking all of these data points into consideration, the overall conclusion of their research was that cinema broadcasts of plays and musicals are “only a ‘minimal threat’ to touring work” and live attendance will most likely not be replaced by streaming broadcasts. Instead, the data suggests that a combination of viewing performances in person and filmed for the internet or movie theaters will have a positive impact on the performing arts.

While no formal studies have been done in the US, these findings from the UK run parallel to what Americans are experiencing with the live broadcasts of musical theater productions on major television networks. Live broadcasts of theater have become increasingly popular in the United States over the past four years. Audiences are now accustomed to the annual tradition of a live musical broadcast, invented by NBC with The Sound of Music in 2013 and adopted by Fox with Grease in 2016. The most recent, NBC’s Hairspray Live, reported the lowest ratings of any musical broadcast despite being heavily promoted by the network and filled with more A-list celebrities than previous broadcasts.

While the ratings are less than desirable for networks, they suggest a certain safety net for live performing arts. The broadcasts generate buzz and interest for musical theater among the general public, they are by no means replacing or disrupting productions taking place in the theater. Data from The Broadway League reported 2015-2016 as a record-breaking year for attendance at Broadway musicals.

- Broadway attendance rates increase by 1.6% during the 2015-2016 season.

- 13,317,980 total tickets sold

- $1,373,253,725 cumulative gross

The production processes of live musical broadcasts have a history of being highly publicized by the networks, giving the public a glimpse into the artistic process.

A more complicated, yet similar, pattern exists between live performance and broadcasts in other art forms. Even though the Metropolitan Opera has been presenting live simulcasts of their productions in movie theaters since 2006, professionals continue to debate whether or not the Met in HD broadcasts benefit the industry at large.

The original intent of the HD simulcasts was to capture a new generation of opera lovers using broadcast technology and convert them into ticket buyers for live performances. However, surveys conducted by the Met indicate that the majority of audiences attending the simulcasts are already fans of opera and in person ticket sales have been steadily declining. Instead, the greatest success of the simulcasts has been the revenue generated from audiences around the world. According to the Met’s 2015 Annual Report, the Met in HD simulcasts earned $26.6 million out of a total earned revenue of $117 million.

Critics of Met in HD point to the declining trends at live opera performances since 2012, despite increases in the numbers attending HD broadcasts. During the 2015-16 season The Met only earned 66 percent of the revenue it could have generated through ticket sales to live performances.

Many leaders of regional opera companies claim Met simulcasts negatively impact their box office sales, but few have data to support their claims. In contrast, David Devan, General Director of Opera Philadelphia told the Washington Post that merely 3 percent of his single-ticket buyers and 6 percent of subscribers also subscribe to the Met HD series. His data indicates that the simulcasts are not discouraging regular opera attendees from attending performances much at all. Christopher Hahn of the Pittburtgh Opera told the Post-Gazette in 2016, "In our specific position in Pittsburgh, I absolutely believe it (Met in HD) has no impact on the audience". Rather, he praised the ability of Met in HD to educate Pittsburgh audiences on operas that his company is unlikely to produce, citing such as Berg’s Lulu, as an example.

Berg's avant garde "Lulu," opened November 5, 2015. The broadcast featured Susan Graham.

Peter Gelb, General Manager of the Met, explained his perspective on this trend to the NY Times in 2013 saying, “we have quadrupled our paying audience”. He compared the decrease in box office ticket sales to the drastic increase in revenue generated by simulcast ticket sales, “the decline of ticket-buyers at the house is just a couple of percentage points”. Rather than considering tickets at the Met to be separate to sales from the simulcasts, he considers his “paying audience” to be just over three million, identifying 800,000 as in person attendees.

After surveying artistic leaders at the largest opera houses in the US, many of whom blame the Met in HD for their declining sales, Anne Midgette of the Washington Post identified several positive outcomes of the HD simulcasts. Ultimately, she concluded that broadcasts will never replace live performance because of technological limitations in terms of capturing the true sound of the human voice. She expressed, “The Met’s HD broadcasts are a forward-looking initiative; they have successfully made use of technology to spread the word of opera. But what they’re spreading is opera product: a fine documentation for those of us already hooked on the form, but without offering new young audiences the visceral thrill that will make them love it”.

Despite technological advancement in the past decade, enthusiasm among dance professionals remains mixed. According to Dance USA: How Audiences Engage, half of the dance professionals participating in their national survey agreed that ‘dance can only be appreciated by experiencing live performance’. The other half of their survey ‘either disagreed or have mixed feelings’. Considering the significant grant awards given to the Martha Graham School of Dance and Siobhan Davies Dance for the purpose of digitizing choreography, it is possible that perceptions within the industry will change.

It is no secret that artists face constant competition. Between competition for work, resources, and audiences; the last thing artists want is to feel like they are competing against technology. At the same time, digital is here to stay and the quality of live broadcasts will only improve with time. It is essential that arts managers take the time to research and understand the implications of streaming and broadcasts in order to be well-informed on the challenges that face their staff. With a thorough understanding of the data behind technological disruption, arts managers can make the 21st century challenges less daunting. Even better, they can demonstrate how their organizations can use technology as an asset rather than give up and accept defeat.

Want a recap of important stats? Check out our infographic below. Do you have a strong opinion on the relationship between live performance and broadcasts or streaming? Most people do. Comment below.