In this month’s Let’s Talk episode, Angela Johnson and B Crittenden are joined by AMT Lab Chief Editor Lutie Rodriguez to discuss the latest update on Google Chrome’s planned elimination of third-party cookies. Angela and B then share their thoughts on NFTs and the Loud & Clear web portal, Spotify’s attempt at increasing royalty transparency.

Referenced Resources

”Chrome’s Cookie Update Is Bad for Advertisers but Good for Google” by Matt Burgess

“Facebook charged with housing discrimination in targeted ads” by Adam Gabbatt

“Beeple sold an NFT for $69 million” by Jacob Kastrenakes

“Why would anyone buy crypto art – let alone spend millions on what’s essentially a link to a JPEG file?” by Aaron Hertzmann

“Jack Dorsey's first ever tweet sells for $2.9m” by Justin Harper

“Performers’ Dance Moves Turned Into Animated NFTs for Games and Apps” by Sebastian Sinclair

“Why Fortnite Is Accused of Stealing Dance Moves” by Steve Knopper

“Spotify Unveils ‘Loud and Clear,’ a Detailed Guide to Its Royalty Payment System” by Jem Aswad

“Musicians Organize Global Protests at Spotify Offices” by Matthew Ismael Ruiz

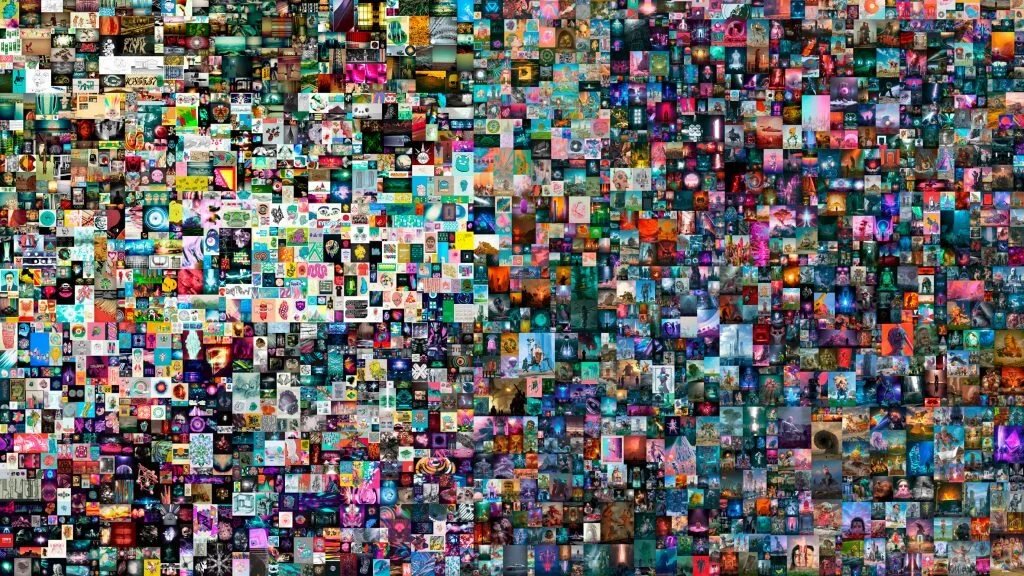

Image 1: Beeple’s collage, Everydays: The First 5000 Days, which sold as an NFT for $69 million. Source: Dezeen.

Transcript

[Musical intro, fades out]

Angela: Welcome to the Let's Talk series of Tech in the Arts, the podcast for the Arts Management and Technology Lab. My name is Angela Johnson, and I'm the Podcast Producer.

B: And I'm B Crittenden, the Technology and Interactive Content Manager.

Angela: Each month we review trending stories and discussions with topics such as streaming, artificial intelligence, marketing, social media, inclusion, fundraising, and much more. Our goal is to exchange ideas, bring awareness, and stay on top of the trends. In this month's episode, we will talk to AMT Lab Editor, Lutie Rodriguez, about Google Chrome's announcement that they're shifting away from third-party cookies, as well as discussing the recent trend of NFTs in the arts, and Spotify's new financial transparency website, Loud & Clear. Hope you enjoy!

[Musical intro, fades in]

Lutie, welcome back. Last time you were here you spoke to us about privacy and just how people working from home can increase the security in their everyday internet use. You've told us that you have some news.

Lutie: I do have some news. Not super new news, but something I read about recently. So, Google Chrome has announced that it's going to stop using third-party cookies. And if you're not familiar with what cookies are, they're small snippets of code that websites can use to track your browsing history. And third party cookies, specifically, are when that information is sent to a different domain than the one that you're on. And it kind of follows you around and that website can know the other websites that you tend to visit, what your online behavior is like, what your interests are, what you buy. Bennett Cyphers, who is a technologist at the civil liberties group called the Electronic Frontier Foundation, has called third-party cookies the most privacy invasive technology in the world. And now, Google Chrome is wanting to get rid of them, which is something Safari, which is the second biggest browser—second to Chrome—limited cookie tracking in 2017, and then Firefox, another large browser, also blocked third-party cookies in 2019. So, this isn't something super revolutionary that Google Chrome is doing, but since it is the largest browser, it's making some waves.

B: So, as an internet user and Chrome user, this sounds great in terms of my own privacy,

Angela: And whenever Google does anything to limit our privacy, I think we all feel a little safer, since they own everything on the internet.

Lutie: Yeah, I think that's what a lot of people maybe have initially thought, but they are pivoting to doing something different, so you're not just able to explore the internet privately in your little utopia. Instead of tracking people with third-party cookies—their individual level activity—they're using AI, putting people in groups. What the AI is doing to sort people into groups is called Federated Learning of Cohorts, or FLOC. So, based on your activity, Chrome, not third-parties, sorts you into a group that has similar activity to you so that instead of advertisers targeting you specifically, they can target a type of group they're trying to reach with their product.

Angela: Which I guess is kind of what a lot of marketing does anyway. It's all the stuff about, like, personas and targeting different groups, so I guess that kind of makes sense as opposed to doing it on an individual level. Of course, I would prefer not to be targeted at all, but, you know.

Lutie: Right, if you're going to be targeted, at least you have people around you.

B: Yeah, I guess all of the data from our internet use is already going into building customer personas and it's a highly valuable field in terms of what our data can do for advertisers and the people who are selling that data. And now, Google has even more, like, oversight over our data. I think it just kind of, in a way, further builds that Google monopoly, because it's not just when you're using Google Chrome, but it's any service that Google owns that now they can use their first-party tracking to collect your data, and that's still a huge share of your internet use. So it's not like you're actually getting privacy. Now, it's just going to the same person, which is Google.

Lutie: Right. Places like Facebook and Google, even with Chrome limiting its third-party cookie tracking, they still have plenty of access to our individual-level data, so advertising via those platforms won't really be affected by this—well, they will be affected, it'll just give them more power compared to others.

Angela: Cool... [laughter]

B: Do we know what this could mean for some of the smaller digital advertisers out there?

Lutie: People have been predicting. Google claims that their new FLOC method is 95% as effective as using third-party cookies for advertising, but people are still suspicious as to if this will take away revenue from smaller advertisers, especially smaller organizations like you mentioned. And they're starting to test this method in March, so now. So, we might get some preliminary information about what that will look like.

Angela: And then we'll have to have you on again.

B: Yeah, because they're starting to test this now and then it looks like their plan is to eliminate the third-party cookies by 2022. So we have some time for the rollout and the testing period and then we'll have you back in 2022, Lutie. [laughter]

Lutie: I don't think I'm going to be here. [laughter] I do have another concerning thing that I found about the FLOC method, and that is that it kind of opens the door for algorithmic biases and discrimination against certain groups because it's just an AI that categorizes people, which is something we tend to want to avoid. And even current advertising methods, like on Facebook, have been shown to have some discriminatory practices, like showing teaching and secretarial jobs to women more often than men. And, Facebook has also been accused by the Department of Housing and Urban Development for ads that discriminated based on race. So, people are a little bit concerned about that with Google Chrome's new AI categorizing people, although Chrome does say that sensitive categories like gender, religion, race will be blocked for use when putting people into FLOC's.

Angela: I mean, it's still a problem of, like, we've talked about on this show before how AI can exhibit racist tendencies, not because programmers are racist, just because there aren't people of color in those jobs making the AI and so their natural, like, biases and, like, there's issues that occur. And, like, even if you don't have the information, I'm sure there are certain ways that, like, people of color might search for certain things that, like, white people might not, like hair products or something like that. And then suddenly, it's just, I feel like that could spiral really easily even if they're not intentionally trying to track that information.

B: Yeah, definitely, that's a good point. So, these categories are based on what, just like, interests?

Lutie: I mean, it's put together based on people's, any online activity and just, I guess, overlaid and then the AI categorizes people who are similar. An article I read compared it to Netflix's recommendations, where they see that someone watched a certain movie and if you also watch that movie, they'll suggest to you things that this other person who liked the movie watched.

Angela: Definitely something to keep an eye on.

B: Just out of curiosity, when you guys go to a site and it warns you that it's, like, tracking cookies, do you ever, like, pay attention to that?

Angela: Sometimes? If it has the option to, like, manage it then I usually will just say no to most of them, but if it doesn’t have, like, an obvious way to do that I usually am just like, “Eh, whatever. I don’t care if they know that I’m shopping for jeans.” I don’t know what I shop for, but...

Lutie: I'm the same way. If the pop-up has, like, "No, don't allow cookies" then I choose that, obviously. But I never take the extra effort to block them myself.

B: I'm embarrassed to say this, but I usually don't even read it, and I just click whatever button seems like will make the pop-up go away.

[laughter]

Lutie: That's what they want, B.

Angela: Playing right into their hands.

B: I know! I need to change this about myself and take the two seconds it takes to actually read it and know what I'm getting myself into. But soon, we won't have to worry about it anymore on Chrome, at least.

Lutie: Well, maybe.

B: Maybe, yeah.

Lutie: Or, whatever group you’re put in. Yeah. We'll see.

B: Well, we should thank you for coming on again.

Angela: Yeah, you're always welcome.

Lutie: Thanks for having me. This was fun.

Angela: So, B, I don't know if you've noticed in the news recently, but there was a whole big thing when the artist Beeple sold his work of art at Christie's for $69 million. Now, that seems pretty normal, but what's interesting is that the art that he sold was an NFT. That stands for non-fungible token; non-fungible means that, like, you can't exchange it for another thing of equal value. So NFT's are a cryptographic asset on blockchain with a unique identification code and metadata that distinguishes them from each other, and unlike cryptocurrencies, they can't be traded or exchanged at an equivalency. So, they're not money. They can be used to represent real world items, like artwork and real estate. So, basically, there is an argument to be made that this person bought a very expensive JPEG.

B: Yeah, yeah, I mean, there's a lot to reflect on here because I think there are a lot of reasons that someone would purchase an NFT, from getting caught up in the trend, to, you know, having the resources to purchase it and so you decide you want to do it, deciding you want to perhaps support an artist who's selling their digital artwork, just for the sake of saying that you own something and got something that was unique—which is definitely not unique to NFTs and could be said for any sort of collector's item—to wanting to invest in something. So, I think one thing that's kind of cool about NFTs is that artists who are making digital artwork are able to sort of build a royalty or build their own payment to themselves into it. There's no middleman because it's on blockchain, and so the money is pretty much going directly to them. And so it's—I actually don't know how many artists are able to benefit from this, but I have seen highlights of artists who previously were not able to sell as much of their digital artwork and are now, like, able to make some money off of their digital art.

Angela: Yeah, definitely. I think the artist who has been making the news, Beeple, has only ever sold, like, a print of his art., and the most he ever sold it for it was like $100. So, this is, like, a big step up because it's able to like be in its form that it's supposed to be. When I first heard this, I was immediately just tired and upset and just like, "Money is nothing; nothing is anything!" [laughter] Just falling into an existential crisis about the whims of the rich. But then, uh, yeah, I don't know, the more I thought about it, the more it's just kind of like, why does anybody buy any art, you know? Like, you could always just, you can see any famous artwork, like, anywhere on the internet, basically. There's no, like, inherent value in owning it, except to own it and to brag about that, to support artists. There's lots of reasons to buy art, and most of them have nothing to do with having a physical thing of art. So, I think we all kind of get hung up on the fact that there's nothing tangible, but I think that also says a lot about how we're valuing digital art.

B: Yeah, echoing what you're saying, there's an article on the website, The Conversation, the author's name is Aaron Hertzmann, and in this article, he writes about value being a social construct, and he draws ties between NFTs and the much-discussed Maurizio Catalan banana taped to a wall at Art Basel, in which—

Angela: It's just a banana taped to a wall.

B: Yeah, the point is just to own it.

Angela: Mhm. Yeah. And I'm pretty sure that when the collector does buy that art, you get, like, instructions as to how to do it at home, basically. And all you need is a banana and some tape, but, you know, people spend millions of dollars.

B: Yeah, they weren't actually buying the banana and the tape; they were buying the right to say they owned this artwork, which is exactly what an NFT is. NFTs, you don't get the copyright. Really, all you get is the property right.

Angela: Your name is on a list somewhere saying that you own it.

B: Right, right. I also question, how accessible are NFT's? I mean, you have to have the ability to, like, have cryptocurrency.

Angela: This is true.

B: Which, at this point, is becoming more and more popular, but to a lot of people who haven't delved into cryptocurrency, it's not something that they're necessarily getting exposed to. And so it just kind of does seem ridiculous.

Angela: Yeah. I mean, just kind of going back to your typical, physical art sales, that's not especially accessible, either. I mean, I think that has more to do with the price than the, like, function, but I think it's still basically available to the same people that it was before, unless we're talking, like, art that's not worth millions of dollars.

B: Yeah, I mean, yeah, one could argue that NFTs are more accessible than going to like an art auction, because you could purchase an NFT for $10.

Angela: Yeah. And I think it's important to note that NFTs aren't going away. Recently, Twitter founder, Jack Dorsey, sold his first ever tweet through an NFT for $2.9 million. And it was for charity—although, through the auction, Jack Dorsey still got 95% of the proceeds. Yeah, and he sold it to a Malaysian buyer, Sina Estavi, who compared the purchase to buying a Mona Lisa painting. So, it does seem at the moment to be a bit of a play thing for the rich, but there are certain ways where I think it could change the art landscape. Also, what we value as art, and what we should value as art.

B: Yeah, and also something that I saw was that the person who won the Beeple piece in the auction appears to be heavily invested in the success of crypto art, which is just another thing to question. Like, as we continue forward, who is investing in these and why? Because this article says the cryptocurrencies that drive crypto art are often considered highly speculative because it is a fad but a fad that has a ton of money behind it.

Angela: I don't know. They keep telling us that Bitcoin is a fad, but it just isn't going away, so, I don't know. It's one of those things where I feel like most people will agree that digital art is art and should be valued. And, I guess just as a result of that, rich people will find a way to buy anything, so you know. But as long as it doesn't just belong to the rich or whatever. Also, when their ownership of the thing doesn't really mean anything in terms of other people's access to it, it's a little bit like, hey, at least cool artists are getting supported.

B: And I also really quickly wanted to mention that this isn't just digital visual art, but also, I was just reading about animated NFTs for games and apps in which a performing arts company has taken dance moves and made them digital, basically, in the form of NFTs. There's a blockchain platform called Enjin, E-N-J-I-N, that enables performing artists and dancers to create an NFTs, and they're called NFT-based Emotes, which they describe as basically an animated emoji. And they can be sold to fans online and used when those fans are participating in video games and apps. So yeah, not just the visual arts.

Angela: Yeah, I wonder if that kind of came out of all the controversy with, like, Fortnite and them stealing dance moves from people and stuff like that.

B: Yeah, I haven't read that, but I totally imagine that it could have. Once again, one good thing is that you're able to get some value out of your, whatever you're creating, whether it be a dance move, or a piece of digital art.

Angela: There is something to be said for, like, stuff on the internet gaining value outside of, like, ad revenue, because I feel like that's the way people make money on the internet. It would be nice if it could just be valued for what it is instead of what it can make for other companies.

B: Yeah, maybe this is the answer to "how do you make money off of art in the digital world?" Here we go. As long as some people out there are still valuing the opportunity to, like, own it and collect it over pressing right-click and doing "save picture as."

Angela: That is something to keep an eye on for sure.

Do you do a lot of music streaming?

B: I do. I stream all of my music and my podcasts on Spotify.

Angela: I use a couple of different platforms, which is not, like—

B: You dabble?

Angela: Yeah, I'm a dabbler. It's not efficient, but that's what I do. I mean, I use Spotify. For my podcasts, I use Apple podcasts. Yeah, I use Spotify because it's cheaper, but I kind of prefer the way, like, Apple Music and Apple Podcasts are just set up, like, it's just a little neater, a little easier to find things. It's less about, like, finding new stuff and more about just keeping the stuff that you have. Which is kind of abstract, but that's always the way I feel about it. But, yeah, so, we're big Spotify users. Most people I know are. It has been, you know, talked about on the internet quite a bit about how Spotify doesn't treat its artists that well. How, you know, people aren't making that much money. There's a lot of controversy. It's hard to make money on Spotify unless you're Joe Rogan, so that is the typical thing that is said. So, Spotify kind of has an answer to this, or an explanation, in the form of Loud & Clear.

B: So Loud & Clear is Spotify's web portal. It has a lot of interactive visualizations and it's really meant to draw the user in and invite them to click around and kind of explore the data they present and their explanations for why they do what they do. And I wanted to mention a little bit of history leading up to this response. The Union of Musicians and Allied Workers launched their Justice at Spotify campaign in October 2021. And more recently, in March, there were a number of protests and demonstrations that were organized by the union that took place at Spotify offices around the world. And really what they were trying to do was call for more transparency in Spotify's business practices, they were trying to call for an end to lawsuits that had been filed against artists, and they also called for a user-centric payment model that pays per cent per stream, as opposed to what Spotify's current model is, which they call “Streamshare,’ which basically, instead of paying an artist a certain fixed amount of money per stream, under Streamshare, every month, an artist's Streamshare is calculated by adding how many times the music owned by a particular rights holder is streamed and divide it by the total number of streams in that market, so that's usually geographic.

So, on Loud & Clear, they pose this example, which is: if an artist receives one in every 1,000 streams in Mexico on Spotify, they would receive one of every $1,000 paid to the rights holders from the Mexican royalty pool. And that total royalty pool for each country is based on the subscription and music advertising revenues in that market. So, as most people probably know, consumers on Spotify are not paying per stream, like, we're paying subscription fees or if you have the free, if you aren't paying for Spotify, there's advertising revenue going to Spotify for that. So, basically, it's known that this Streamshare model actually hurts niche artists. Actually, in 2017, there was a Finnish study that found that under the model that Spotify currently uses, songs from the most popular artists, so the top 0.4%, got 9.9% of royalties. And applying this user-centric model that the union is calling for, and a lot of others are calling for, researchers found that the same top 0.4% of artists would then just collect 5.6% and therefore, like, more widely distribute that revenue. I think it's also worth mentioning that money is not going straight to artists; it's going to rights holders. And then, it's up to the rights holders to determine how the money is distributed, and Spotify has nothing to do with the contracts that rights holders work out with their artists. So, they really aren't able to speak to that out Loud & Clear, and they say that many times.

Angela: Yes, the music industry is a little bit broken, and it's not entirely Spotify's fault. One of the things I found really interesting on the website was just the way they kind of break down their artists into different personas—it always comes back to personas—like, they have, like, “specialists” and, like, “established songwriter,” and of course they have, like, “songwriters and producers,” which are the rights holders, and for instance, like, those people just make billions of dollars—well, that's the total global revenue. But, like, in 2019, Spotify paid out $3.3 billion to songwriters and producers, for instance, the, like, specialist persona, which usually gets average monthly listeners around 214,000, only will make about $36,000-$37,000 per year on Spotify. And it's like, if you're only on Spotify, you're not exactly making it big in the music industry. But it just seems like a weird response to people protesting the way Spotify pays artists, and then Spotify being like, "Here's a very pretty website of how we pay them." But like, they're not, like, changing anything. It's just, like, trying to shove the blame onto someone else. And, I don't know, it's just unsatisfying, I guess.

B: Yeah, I mean, part of me appreciates what they're doing, because at least they're doing something and trying to share some information, but I do think it's not the most appropriate title because while it is loud, it is not clear. I mean, they're trying to lend some clarity to it and to lay things out in one place, but I also read somewhere, someone sort of criticized the fact that they did this in-house as opposed to having someone outside lend sort of an unbiased perspective on what their practices are and sharing that with everyone. Because obviously, there's still probably quite a bit of, not tampering, but they're trying to brand themselves and depict themselves in a certain light. I don't know if you got the same vibe, but in Loud & Clear, on the web portal, they really, really drive home, the fact that—and they provide a lot of data and interactive data visualizations on the year-on-year growth in artists reaching their different levels of royalty payouts. So it shows the number of artists who can generate royalties of $50,000 or more per year on Spotify has increased by 80% in the span of four years. And that is the same for every single level of royalty payout, so they're basically just trying to say that because of the streaming economy and because of Spotify itself, artists are generating more revenue on the whole and just getting more exposure and more plays, and partially, I think they could attribute that to the algorithms and the playlists.

Angela: I don't know, I feel like Spotify, the way, also, like, yes, artists are getting more exposure and, like, maybe they're getting more plays, but it's almost like every stream of their song is worth less, because so many people are just like, "Yeah, it's on a playlist" so they play it, but they're not like listening to it. You're not like, "Oh, I wonder who this is?" Like, it's just harder to garner a following, even if you get a lot of streams on Spotify.

B: Mhm, it's not as intentional as someone seeking out an artist to listen to their music. By the way, I feel guilty about the fact that I listen to Spotify. I don't feel good about it.

Angela: I know, I don't want to but also, you know, convenience is king or whatever.

B: Yeah, and you were talking about someone streaming a song doesn't seem like it's as valuable. And part of that is true because there's no, like, fixed amount for that stream. I could stream the same song all day, like, for 24 hours, and that artist is not necessarily getting anything out of that, directly. So, yeah, I wanted to mention that earlier—I was talking about these user-centric payment models. And Spotify does counter this idea by suggesting that switching to this model would then inflate Spotify's administrative costs to the point that it would eliminate the potential revenue gains for the niche or less popular artists. However, from what I've read, there hasn't necessarily been any evidence to support that particular claim.

Angela: Yeah, it's like you said, I wish they had done, like, a third-party kind of thing. Like, it just, because it's in house, everything that they're saying and, like, every defense that they have just feels hollow. And, like, I have no reason to believe that it is the best thing for artists, because they just want to keep their company alive, you know?

B: Yeah.

Angela: So, I don't know.

B: Definitely, our listeners should go check it out. It's loudandclear.byspotify.com.

Angela: It's a really interactive website. It's fun to navigate.

B: Yeah! There's a video that illustrates what the payment model is, essentially, as much as they can share, which is not very much. But, yeah, it's very interactive. And it's very, like, they do a lot of hitting you over the head with the fact that the number of artists reaching certain levels of royalty payouts are growing. But one thing I was curious about that they didn't provide is, like, what is the proportion of artists to the total number of artists that are on Spotify?

Angela: Yeah, I was looking for that too.

B: Are those numbers increasing only because more artists are putting their work out on Spotify?

Angela: It's hard because, I don't know, I feel like so many people are using Spotify. Like, you can't be an artist and not have your music on Spotify, unless you're Beyoncé. And even then, people were mad. It's good for, like, consumers and not necessarily great for creators, which is a lot of things in the art world at the moment.

B: Well, I guess it doesn't hurt that much to have your work on Spotify, but—

Angela: As long as it's other places and it's not like replacing the revenue that they're getting other places, which it probably is, I mean—

B: Yeah, that's the problem it’s, like, now one of the only places that people are consuming things. We've also already talked about this on the podcast, is with Covid, limiting performing artists' abilities to be touring, which is where they get the bulk of their revenue, they're extremely limited to how people are consuming music. Not a lot of people are buying music anymore. They're streaming. I don't know, do you have any conclusions?

Angela: I don't know. Like, I appreciate the fact that they made an effort to be transparent. Not, like, a huge effort, but they did make one. And a lot of companies, like, they don't have to. They're Spotify. Like, they're not going to lose money if they, like, how many people would really leave Spotify if they weren't being transparent? So, you know, they did something. They responded in any way to a protest, and that's always exciting in this day and age. But, I don't know, I still want more from Spotify. I want them to be trying harder to help artists and, like, feel like they are supporting artists and not just trying to make money from consumers.

B: I agree.

Angela: Thanks for listening to the AMT Lab podcast. Don't forget to subscribe and to leave a comment. If you would like to learn more, go to amt-lab.org. That is A-M-T dash L-A-B .org. Or, you can email us at amtlabcmu@gmail.com. You can also follow us on Twitter at Tech in the Arts, or on Instagram, Facebook, or LinkedIn at Arts Management and Technology Lab. You can find the resources that we referenced today in the show notes. Thanks for listening. See you next time.

[Musical outro, fades in]