INTRODUCTION

Post-COVID, institutions across the United States have made the commitment to increasing diversity, equity, accessibility, and inclusion (DEAI) efforts. From 2019 to 2023, the Leadership Exchange in Arts and Disability (LEAD) Conference experienced a 66.67% increase in attendance. In the years following 2020, several museums released statements reaffirming their stance on either continuing or implementing more extensive DEAI practices— across the board. This renewed focus towards DEAI initiatives represented a step towards art museums becoming more welcome to diverse audiences.

To what standards do we hold accessibility measures now?

The American Alliance of Museums (AAM) conducted an Excellence in DEAI 2022 Report, which analyzed inclusivity efforts across cultural institutions and offered resources for museum professionals to implement into their own practice.

While the report offers valuable recommendations, it does not specifically mention neurodiversity as an example for consideration by arts institutions. The report even acknowledges this gap (see figure 1), indicating that, even with comprehensive DEAI strategies, there is still significant work needed to cover all “specific and contextual” needs.

This led to the following question: How effectively are art museums actually providing neurodiverse accessibility, if at all? Additionally, what strategies can be implemented to enhance inclusivity for neurodiverse visitors and support educators who aim to bring neurodiverse students into these spaces? To properly address these needs, art museums must first understand what it means to be "neurodivergent."

PROVIDING CONTEXT: WHAT IS “NEURODIVERGENT”?

For art museums, knowledge of and consideration of neurodiversity must be a requirement within the context of accessibility and DEAI efforts. Neurodiversity itself refers to a wide spectrum of neurological differences in individuals.

Beneath the umbrella of neurodiversity are conditions such as autism spectrum disorder (ASD), attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), among other learning disabilities. In 1998, sociologist Judy Singer introduced the term neurodiversity to advocate for the inclusion of “neurological minorities”. Since then, it has been used to describe individuals with a variety of neurological conditions, alongside other useful vocabulary tied to the phrase. By employing this terminology (i.e. neurodiverse individuals, an autistic person), we can acknowledge and respect the diverse range of neurological experiences that exist and, additionally, the unique perspectives of individuals within the neurodivergent community.

PROVIDING CONTEXT: WHAT DOES IT MEAN TO BE NEURODIVERGENT?

Neurodivergent individuals interact with the world in diverse ways, experiencing variations in cognitive functions, learning styles, sensory processing, communication methods, and behaviors. There may be additional physical behaviors including self-stimulating actions (commonly referred to as “stimming”) as a method of self-regulation, or heightened sensitivity to light and sound. The result? Each individual’s experience with their neurodivergency is entirely unique to them.

While there may be overlap with the needs of those with physical disabilities, neurodiverse accessibility extends beyond physical accommodations like ramps and elevators. It involves creating environments that consider the individualized needs of neurodivergent individuals. Because of this, art museums cannot reasonably adopt a one-size-fits-all solution to addressing the barriers that neurodivergent individuals and educators bringing neurodivergent students into museum spaces may face. However, museums can still make concerted efforts to address as much as they can.

NEURODIVERGENCY WITHIN THE ARTS: WHY ADDRESS IT?

A significant portion of the global and U.S. population are considered neurodivergent. The increasing prevalence of this population over the years means a growing necessity for recognition by institutions, in terms of accessibility resources and accommodations offered. By addressing specific neurodivergent needs, museums can create the supportive environments they are committed to (and, if not, should be committed to) providing.

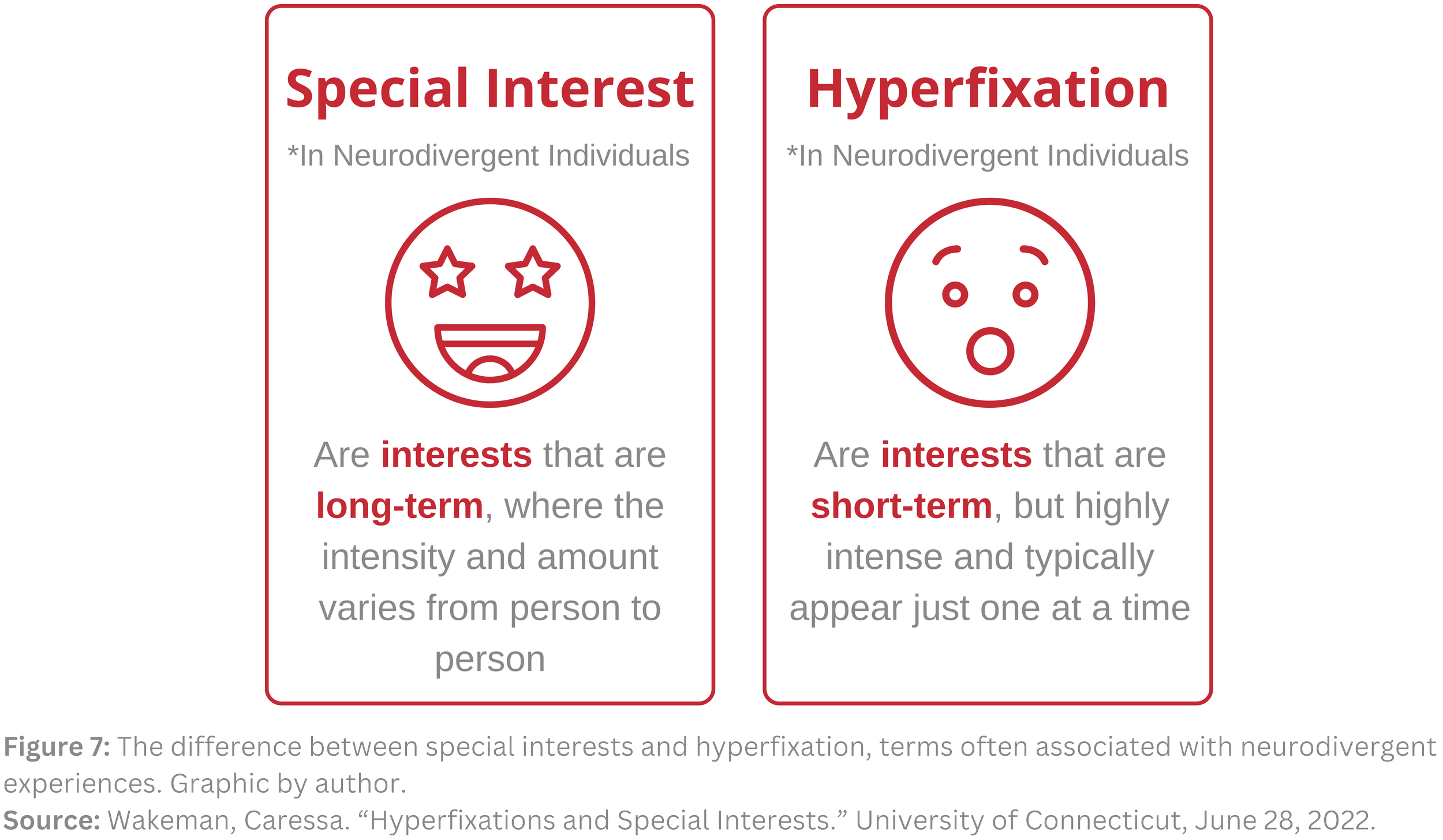

As featured in the article ADHD Goes to the Museum, one survey respondent points out: "...Museums and exhibits often focus on specific topics or niches such as musical instruments, photography, or history, which can be someone's special interest or current hyperfixation." In another survey conducted by ADDitude, 89% of respondents actively enjoy visiting museums and cultural spaces, especially any that include “...interactive, hands-on experiences, outdoor exhibits, and self-guided tours.” Art museums have the potential to be incredibly appealing to neurodivergent individuals if they recognize the importance of reaching this audience and take into consideration their needs, such as the aforementioned interactive and hands-on elements.

RECOMMENDATIONS: DESIGNING AN ART MUSEUM FOR NEURODIVERGENT POPULATIONS

Neurodiverse individuals explore and experience art museum settings differently. They may require accommodations, such as sensory-friendly exhibits, interactive experiences, and flexible programming in order to fully engage with a museums’ offerings. Based on the findings, my recommendations to art museums are as follows:

AVAILABILITY OF SIMPLE TECHNOLOGY

A number of museums provide simple tools and technology to accommodate neurodivergent needs that might arise and/or impede visitors’ experience. “Technology,” for the purpose of this section, is defined as a method or process used to achieve a task, whether through electronic means or physical tools. This definition is to clarify that technology encompasses more than just electronic devices and includes a broader range of tools and processes.

Figure 8 provides some key examples, how these can be implemented, and what their impact may be. One issue that can arise for neurodivergent individuals is overstimulation, which is when a person surpasses their threshold for sensory input. An ‘overload’ of the senses occurs, and the brain becomes overwhelmed by the stimuli in the environment. Within an art museum setting, what could lead to overwhelm could be anything from the volume levels to the bright, fluorescent lights. For art museums who might be unable to anticipate all factors which might trigger overstimulation, sensory kits and simple tools can be useful in reducing the overwhelm neurodivergent guests may experience and allowing them to enjoy the museum with less distraction.

2. UNIVERSAL DESIGN FOR ART MUSEUMS

While it is true that there is no exact way to cover all bases when it comes to providing neurodiverse accessibility, art museums can consider modifying their offerings to align more closely with the principles of universal design. Universal Design (UD) is defined as “the design of products and environments to be usable by all people, to the greatest extent possible, without the need for adaptation of specialized design.” When applied to learning, Universal Design for Learning (UDL) is achieved and considers whether the following is represented:

By offering flexibility in how visitors can engage with an art museum’s exhibits and materials, those of all abilities can find ways to customize their experience to their preferences. An example of how UDL can be applied is found at the Museum of Pop Culture, which offers visitors a “sensory rating card” (see figure 10). The cards indicate the different types and levels of stimulation that can be expected in each exhibition space.

This includes detailing how all the senses (touch, hearing, sight, smell, and bodily sensations/movement) may be impacted or activated. An adaptable, and low-cost, tool like this is immensely helpful because many neurodivergent people struggle with the ability to process new information, manage their time, and decision-making. By establishing clear expectations of what will be seen and felt, neurodivergent individuals can make informed decisions about what suits them best and avoid exhibits that might not be enjoyable. Therefore, they can focus on interacting with the exhibits that genuinely interest them and align with their needs.

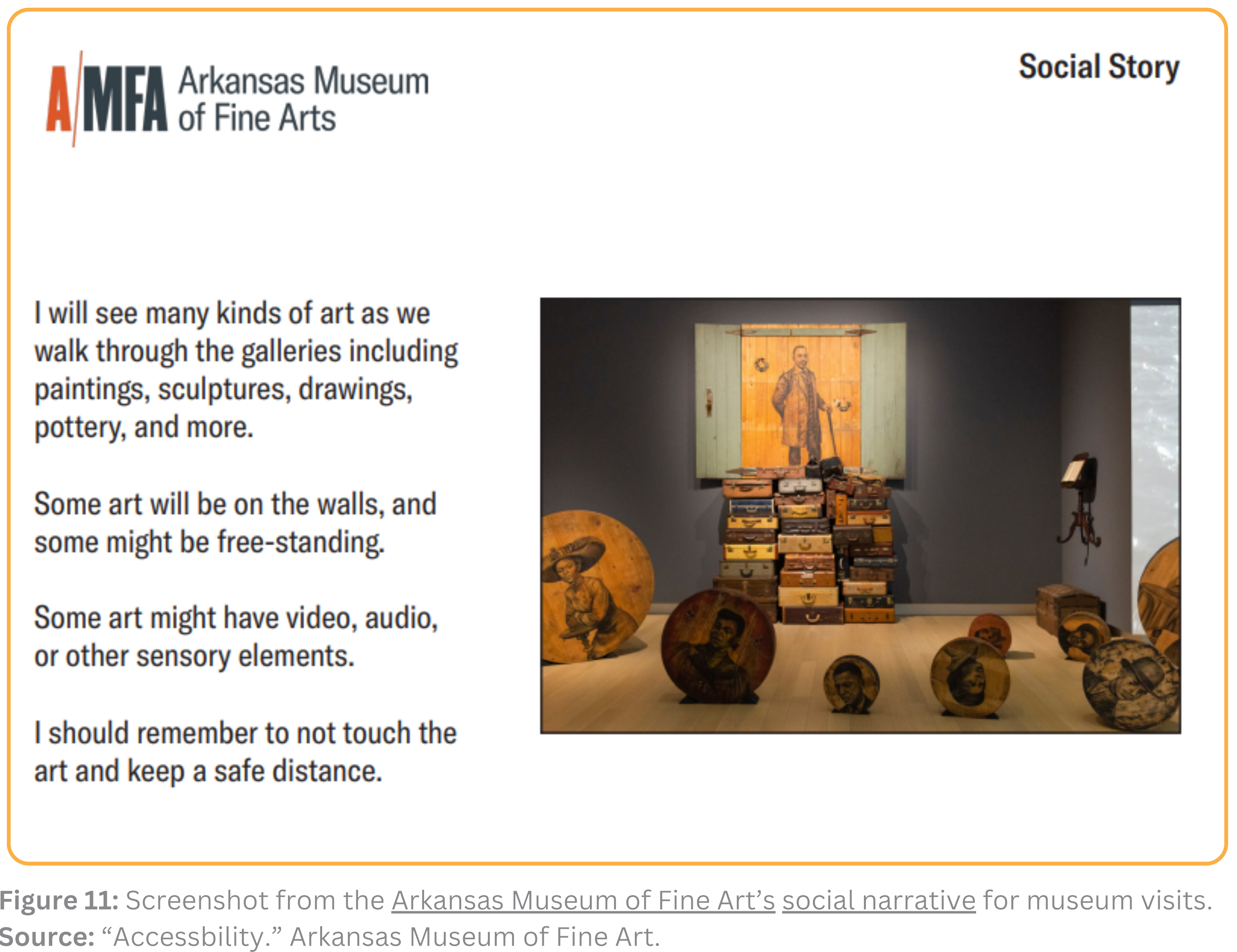

Similar to this concept are social narratives, which provide “objective statements” about social situations. They act as a sort of ‘trial run’ for the sequence of events that a neurodivergent individual will need to know about ahead of time. The Arkansas Museum of Fine Arts provides social narratives for both museum visits and experiencing a tour, which would be incredibly helpful to provide to a neurodivergent student brought in with a school group.

Neurodivergent visitors and students bring diverse perspectives and process information uniquely. Just as there are various ways they learn, there are numerous ways for art museums to start integrating UDL principles. The “plus-one” method can be considered for those art museums who may feel overwhelmed about overhauling their accessibility approach and is a strategy that involves adding just one new approach. The key is to take the first step and start.

NEURODIVERGENCY WITHIN THE ARTS: WHY ADDRESS EDUCATORS?

Why should art museums care about supporting educators who may be bringing neurodiverse students into their spaces?

Field trips in U.S. schools have been decreasing over time, similar to the decline of extracurricular activities and dedicated time towards art, music, and recess. Various factors have impacted the ability of educators, and schools, to facilitate field trips for students (socioeconomic reasons, underfunded art programming within public schools, for example). However, well-planned field trips and community-based learning can enhance classroom education by offering experiences beyond the classroom environment to students. For neurodivergent students, these outings can spark new interests, bridge classroom lessons with real-world applications, and enhance social-emotional learning.

By investing in resources that align with the needs of neurodivergent visitors and educators with neurodivergent students, art museums can ensure equitable access to valuable educational opportunities and attract a more diverse audience.

-

“(1) The Language of Neurodiversity: Terms and Definitions in the Age of Inclusivity | LinkedIn.” Accessed June 11, 2024. https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/language-neurodiversity-terms-definitions-age-susan/.

American Alliance of Museums. “Museum Accessibility: An Art and a Science,” October 21, 2022. https://www.aam-us.org/2022/10/21/museum-accessibility-an-art-and-a-science/.

American Alliance of Museums. “Neurodivergent Needs: A Q&A with ADDitude Magazine,” February 16, 2024. https://www.aam-us.org/2024/02/16/neurodivergent-needs-a-qa-with-additude-magazine/.

American Alliance of Museums. “Tips for Creating Accessible Museums: Universal Design and Universal Design for Learning,” November 27, 2023. https://www.aam-us.org/2023/11/27/tips-for-creating-accessible-museums-universal-design-and-universal-design-for-learning/.

“Ask an Autistic #13 - What Are Special Interests? - YouTube.” Accessed May 29, 2024. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ytWwFr5_pbY.

Castillo, Ruth Igielnik, Elizabeth Grieco and Alexandra. “Evaluating What Makes a U.S. Community Urban, Suburban or Rural.” Pew Research Center (blog), November 22, 2019. https://www.pewresearch.org/decoded/2019/11/evaluating-what-makes-a-us-community-urban-suburban-or-rural/.

CDC. “Data and Statistics on Autism Spectrum Disorder.” Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD), February 22, 2024. https://www.cdc.gov/autism/data-research/index.html.

“Census Reporter: Making Census Data Easy to Use.” Accessed May 29, 2024. https://censusreporter.org/.

Cleveland Clinic. “Neurodivergent: What It Is, Symptoms & Types.” Accessed May 29, 2024. https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/symptoms/23154-neurodivergent.

Creative Differences: A Handbook for Embracing Neurodiversity in the Creative Industries. Universal Music, 2020.

“Definition of TECHNOLOGY,” June 4, 2024. https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/technology.

Deloitte Insights. “Creating Support for Neurodiversity in the Workplace.” Accessed May 29, 2024. https://www2.deloitte.com/us/en/insights/topics/talent/neurodiversity-in-the-workplace.html.

“Disability Language Style Guide | National Center on Disability and Journalism.” Accessed June 22, 2024. https://ncdj.org/style-guide/.

“Diversity, Equity, Accessibility, Inclusion (DEAI), & Anti-Racism – American Alliance of Museums.” Accessed May 29, 2024. https://www.aam-us.org/topic/diversity-equity-accessibility-inclusion-anti-racism/.

Doyle, Nancy. “Neurodiversity at Work: A Biopsychosocial Model and the Impact on Working Adults.” British Medical Bulletin 135, no. 1 (September 30, 2020): 108–25. https://doi.org/10.1093/bmb/ldaa021.

Editors, ADDitude. “ADHD Goes to the Museum.” ADDitude (blog), August 20, 2023. https://www.additudemag.com/overstimulated-understimulated-museum-accessibility-adhd/.

Felton, Amber. “What Is Hyposensitivity?” WebMD. Accessed June 11, 2024. https://www.webmd.com/brain/autism/what-is-hyposensitivity.

“Find a Museum.” Accessed April 28, 2024. https://ww2.aam-us.org/about-museums/find-a-museum.

Forbes Health. “What Does It Mean To Be Neurodivergent?,” October 4, 2022. https://www.forbes.com/health/mind/what-is-neurodivergent/.

Gold, C., T. Wigram, and C. Elefant. “Music Therapy for Autistic Spectrum Disorder.” The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, no. 2 (April 19, 2006): CD004381. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD004381.pub2.

Marco, Elysa Jill, Leighton Barett Nicholas Hinkley, Susanna Shan Hill, and Srikantan Subramanian Nagarajan. “Sensory Processing in Autism: A Review of Neurophysiologic Findings.” Pediatric Research 69, no. 5 Pt 2 (May 2011): 48R-54R. https://doi.org/10.1203/PDR.0b013e3182130c54.

MEd, Nicole Baumer, MD, and Julia Frueh MD. “What Is Neurodiversity?” Harvard Health, November 23, 2021. https://www.health.harvard.edu/blog/what-is-neurodiversity-202111232645.

Museum, The Walters Art. “Diversity, Equity, Accessibility, and Inclusion Goals,” n.d.

“Neurodiversity in the Workplace.” Accessed May 29, 2024. https://askearn.org/page/neurodiversity-in-the-workplace.

“Neurodiversity, Neurodivergent, Neurodiverse, Neurotypical – Editorial Style Guide.” Accessed May 29, 2024. https://editorial-styleguide.umark.wisc.edu/term/neurodiversity-neurodivergent-neurodiverse-neurotypical/.

Rondeau, James. “An Update on Our Racial Justice and Equity Work,” June 3, 2021. https://www.artic.edu/articles/928/an-update-on-our-racial-justice-and-equity-work.

“Sensory Differences - a Guide for All Audiences.” Accessed June 11, 2024. https://www.autism.org.uk/advice-and-guidance/topics/sensory-differences/sensory-differences/all-audiences.

SFMOMA. “March 2021 Update: Institutional Commitments.” Accessed May 29, 2024. https://www.sfmoma.org/dei-actions/dei-update-march/.

“Stimming: What Is It and Does It Matter? | CHOP Research Institute.” Accessed June 11, 2024. https://www.research.chop.edu/car-autism-roadmap/stimming-what-is-it-and-does-it-matter.

Teach Online. “Designing for Neurodiversity,” April 11, 2023. https://teachonline.asu.edu/2023/04/designing-for-neurodiversity/.

Team, ADDA Editorial. “ADHD & Hyperfixation: The Phenomenon of Extreme Focus.” ADDA - Attention Deficit Disorder Association (blog), March 20, 2023. https://add.org/adhd-hyperfixation/.

“The Push and Pull for Accessibility,” October 25, 2023. https://www.arts.gov/stories/blog/2023/push-and-pull-accessibility.

“The Value of Art Therapy for Those on the Autism Spectrum,” March 31, 2017. https://www.3blmedia.com/news/value-art-therapy-those-autism-spectrum.

“Universal Design: Process, Principles, and Applications | DO-IT.” Accessed June 11, 2024. https://www.washington.edu/doit/universal-design-process-principles-and-applications.

Wakeman, Caressa. “June 23, 2024 | Neurodiversity in Engineering,” June 28, 2022. https://neurodiversity.engineering.uconn.edu/2022/06/.

“WebAIM: Evaluating Cognitive Web Accessibility.” Accessed June 11, 2024. https://webaim.org/articles/evaluatingcognitive/.

“What Do We Know About Noise Sensitivity in Autism?” Accessed June 11, 2024. https://www.kennedykrieger.org/stories/interactive-autism-network-ian/noise-sensitivity-autism.

World Economic Forum. “Explainer: What Is Neurodivergence? Here’s What You Need to Know,” October 10, 2022. https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2022/10/explainer-neurodivergence-mental-health/.

Yum, Lori Deuchar. “ADHD Symptoms Unmasked by the Pandemic: Diagnoses Spike Among Adults, Children.” CHC Resource Library, March 31, 2021. https://www.chconline.org/resourcelibrary/adhd-symptoms-unmasked-by-the-pandemic-diagnoses-spike-among-adults-children/.