Digitization efforts for cultural heritage are standard practice for institutions of all sizes, ranging from simple metadata records to elaborate 3D renderings of ancient sites. While the discussion of digitally preserving cultural heritage at large is prominent, the intersection of intangible cultural heritage and digitization practices requires specific recognition. This includes understanding intangible cultural heritage and its value for society. This article examines the emerging and evolving landscape of intangible cultural heritage, its global impact, and current efforts for safeguarding these intangible items in order to address how this field is being organized and used.

The Intangible Cultural Heritage Landscape

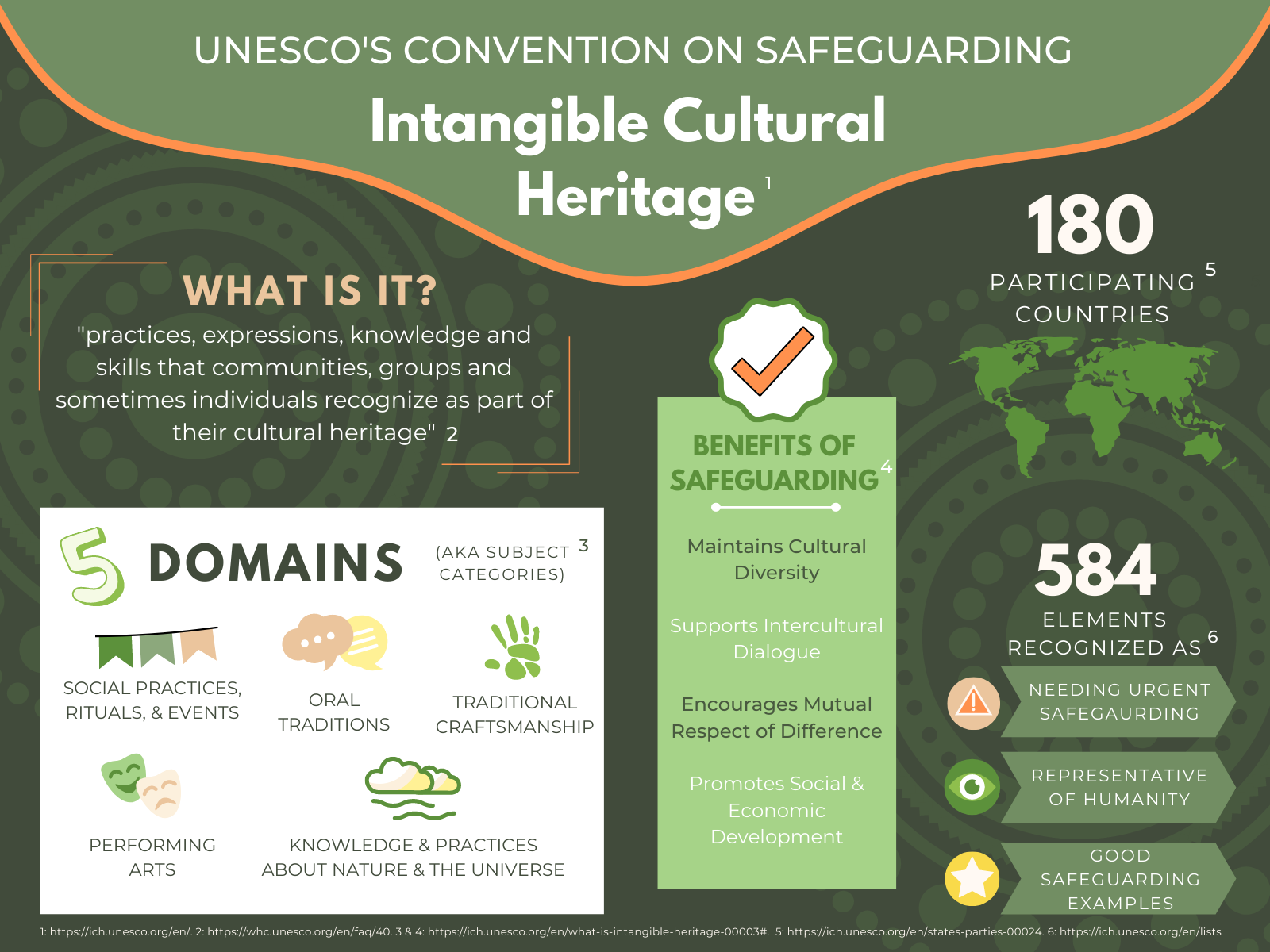

Cultural heritage has a long lineage of recognition through laws and policies on national and international scales. UNESCO’s 1972 World Heritage Convention, which categorized cultural heritage as the monuments, sites, and groups of buildings with universal value as determined through historical, artistic, scientific, aesthetic, or ethnological or anthropological lenses. As the term evolved, it grew to include collections of objects and then expanded through the differentiation between tangible and intangible cultural heritage. The Convention for Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage in 2003 delineated this difference by establishing that in contrast to traditionally recognized tangible cultural heritage, ICH is “the practices, representations, expressions, knowledge and skills handed down from generation to generation”(Figure 1). As such, this “living heritage” values the immaterial creative process behind a cultural manifestation and not merely the manifestation itself. It also encourages the continued development of ICH practices, drawing in the importance of the home community that is identifying, practicing, and changing the subject matter through communal use.

Figure 1: Infographic on UNESCO’s Convention on Safeguarding Intangible Cultural Heritage

Proposals are ongoing regarding expansion of intangible heritage elements. Currently, ICH-driven initiatives often adopt UNESCO’s five generalized categories for personal use. These domains are:

Oral traditions and expressions, including language as a vehicle of the intangible cultural heritage

Performing arts

Social practices, rituals, and festive events

Knowledge and practices concerning nature and the universe

Traditional craftsmanship

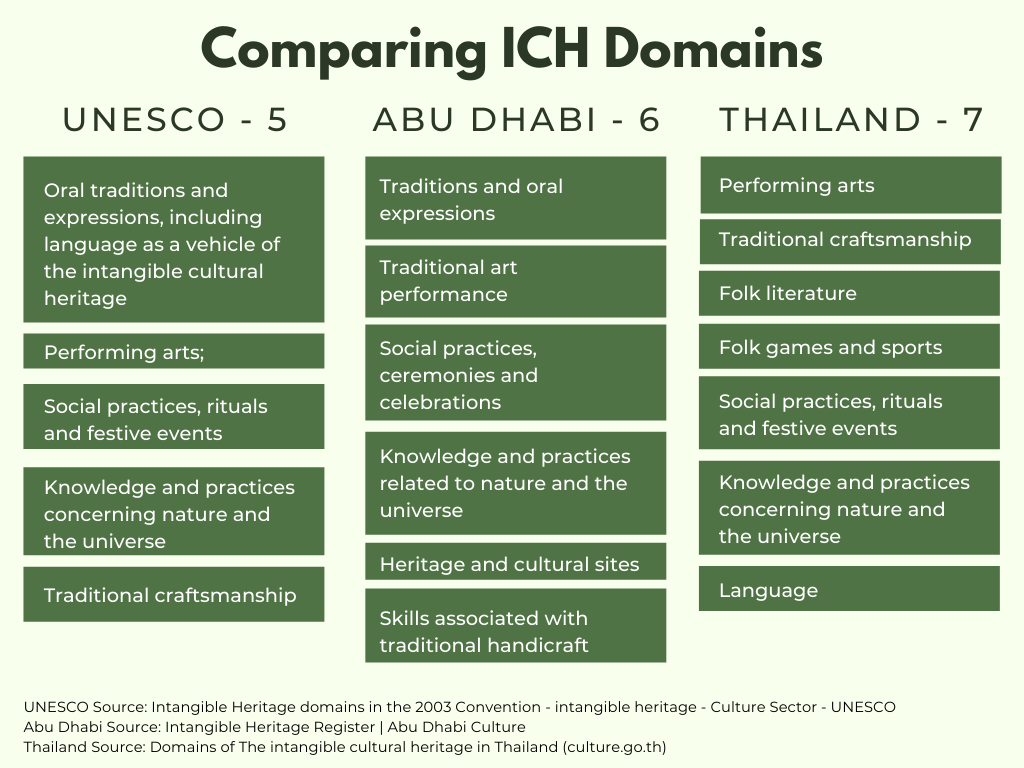

While these are frequently adopted by organizations, they are also often adapted or extrapolated within specific categories. For example, Abu Dhabi uses six stated domains and Thailand seven (Figure 2). In addition to categorization, a fundamental understanding of what intangible objects can be considered ICH is growing. For example, some scholars are arguing for the inclusion of acoustic measurements of cultural heritage sites. These measurements serve as a record that could assist in the reconstruction of a building or recreation of how audio sounds within a space. It also potentially offers an overlooked factor of spatial ICH, recognizing the uniqueness of an enclosed space and its effects on how sound is produced and experienced. Following the fire that destroyed the roof of Notre Dame de Paris Cathedral, authorities consulted measurements taken of the space’s unique and iconic acoustics to determine the best methods for reconstruction. Workers were able to make data-informed choices by analyzing building material selections within virtual models of the space and its pre-fire acoustic measurements.

Figure 2 - Comparing ICH Domains

Globalization Effects

Although inherently valuable, safeguarding ICH represents a movement to confront significant societal issues. Partly due to globalization and partly due to modernity, cultures are merging and becoming less distinct. As the world becomes increasingly homogenized, ICH elements are vulnerable to being lost or forgotten. Similarly, the history of colonization throughout the world elevated the culture of the empowered nation and sought to eradicate culturally unique traits, both tangible and intangible, of the dominated culture. This effectively diminished the dominated culture’s ability to transmit ICH between generations, causing loss of ICH. But safeguarding ICH can lead to benefits that directly counteract these issues. According to UNESCO, the benefits include maintaining cultural diversity, supporting intercultural dialogue, encouraging mutual respect of difference, and promoting social and economic development. This is due to the communal nature of safeguarding that occurs, rebalancing power dynamics to encourage respect, and promotion of minority communities.

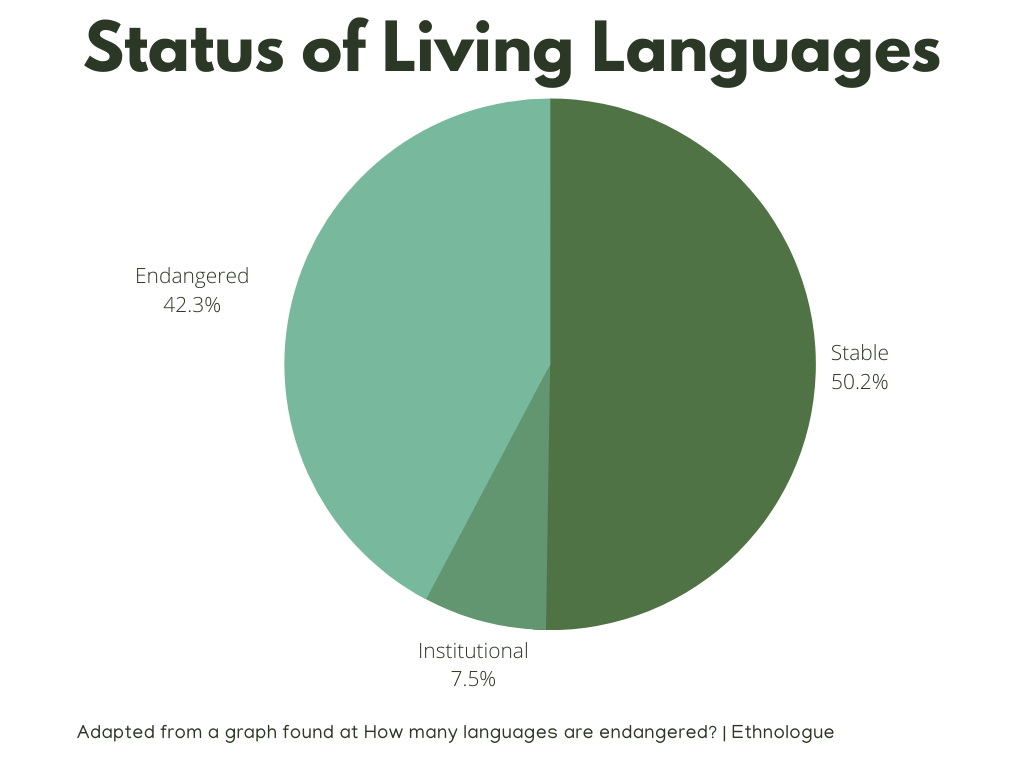

Figure 3 - Status of Living Languages

Unfortunately, ICH continues to face imminent risks of loss. Two examples are that of language and traditional crafts. Out of 7,139 known languages, 3,018 are endangered, with research showing that a language dies every 40 days - with a rising trajectory of loss reaching 16 languages per year by 2080 and 26 languages by the middle of the upcoming century (Figure 3). In the United Kingdom, a 2021 assessment of 244 traditional crafts identified four extinct crafts, 56 classified as critically endangered, and 74 as endangered (Figure 4). Safeguarding ICH must be a priority to minimize the inevitable loss for local and global communities.

Figure 4 - Status of Traditional Crafts in the UK

Safeguarding & Preservation Practices

As of July 2020, 180 countries adopted the UNESCO ICH Convention. However, many countries are engaging in ICH safeguarding and preservation efforts apart from UNESCO. As of the date of this article’s publication, the United States has not adopted this convention but the federal government partners on several ICH projects. Additionally, this work is conducted by non-government organizations. The number of actors working with ICH can result in vast unknowns regarding alignment with international standards. While distribution among a variety of actors protects data, it makes the discovery and sharing of information and assets difficult to collect.

Given the scale of ICH efforts globally, identifying a common process is helpful to understand how these efforts are being conducted. With a large contingency of nations subscribing to UNESCO’s convention, its suggested safeguarding measures provide guidance for how hundreds of projects are being conducted internationally. The essential work is identifying and inventorying instances of ICH by collaborating with communities and their constituents. From there, the UNESCO convention suggests seven different measures for safeguarding. For countries that have signed the convention, required measures include inventorying work with full community support, creating policies, and entities that specialize in ICH caretaking, emphasizing research, implementing additional safeguarding practices as needed, and submitting regular reports regarding the state of national ICH elements. Nominations for elements to be internationally recognized undergo a nomination and consideration process and are voted on annually. As of publication, UNESCO has recognized 584 elements of ICH from 131 countries (Image 2). Elements are divided into three lists:

List of Intangible Cultural Heritage in Need of Urgent Safeguarding

Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity

Register of Good Safeguarding Practices

The result of having ICH elements inscribed on these lists increases the international audience’s appreciation of the diversity, importance, and need for safeguarding these instances.

“…the term ‘safeguarding’ recognizes the dynamic nature of ICH and emphasizes the transmission of the subject matter to ensure future expressions.”

ICH’s continued growth, both in recognized iterations and in attention from the public, includes utilized terminology and the expansion of what this field could encompass. Terminology addressing the field is still in flux with the conflicting use of both ‘safeguarding’ and ‘preservation.’ UNESCO argues that the term ‘safeguarding’ recognizes the dynamic nature of ICH and emphasizes the transmission of the subject matter to ensure future expressions. In contrast, the European Union uses ‘preservation’ to recognize the transient nature of ICH and the process of capturing iterations of past or present expressions.

Given the variation in terminology and expansion of recognized elements of ICH, this field necessitates the inclusion of digitization standards and the creation of digital heritage. In its Charter on the Preservation of the Digital Heritage, UNESCO digitization practices observe both protection and preservation values while layering on technological issues of combatting obsolescence, ensuring digital content’s integrity and continuity, and maintaining complex infrastructures. Terminology could determine the digitization methods chosen, affecting collection and curation practices. For example, if an instance of ICH is the focus of safeguarding, it may determine that digitization efforts focus on collecting and transmitting the ICH to other community members for learning methods to be repeated. Conversely, ICH subject to preservation could desire digitization tools tailored for capturing and distributing the subject to other communities’ benefits of appreciation, education, or entertainment. Tools and platforms for acquiring and disseminating ICH information could vary when the purposes of and audiences for gathered materials differ.

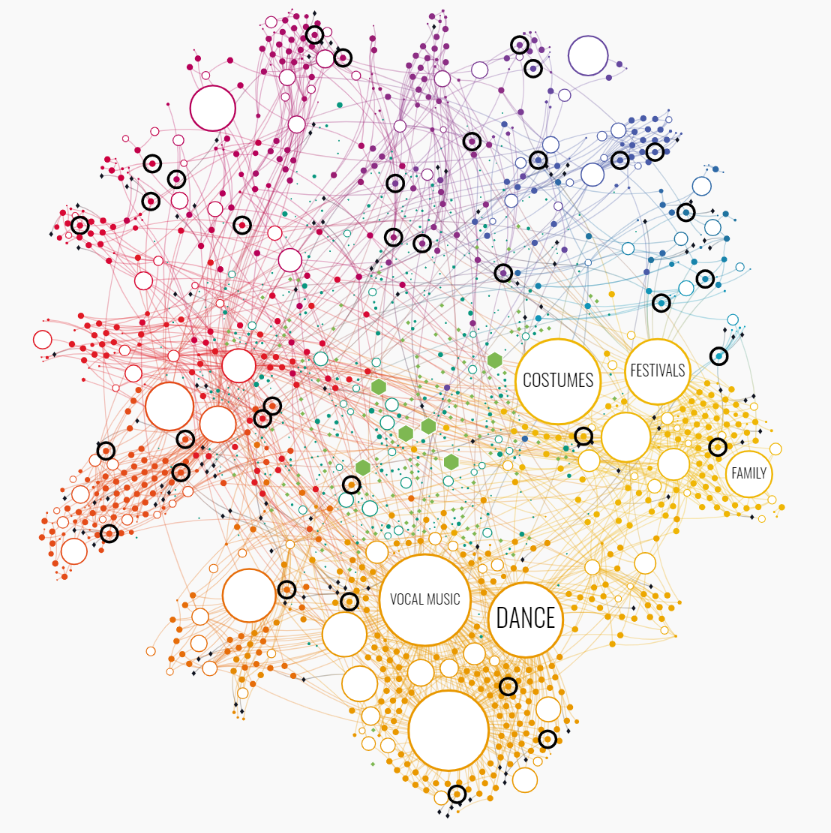

Image 1 - Picture taken of UNESCO interactive work: Constellation of UNESCO Elements.

Navigating ICH represents an expanding interdisciplinary and cross-convention field of inquiry. But understanding its context is necessary for understanding the decisions being employed by organizations for safeguarding and preservation. Recognizing the aspects surrounding ICH influences actions taken by organizations and the tools selected for digitizing works.

+ Resources

American Institute of Physics. 2019. “Reconstructing the Acoustics of Notre Dame.” May 6, 2019. https://phys.org/news/2019-05-reconstructing-acoustics-notre-dame.html.

Brezina, Pavol. 2013. “Acoustics of Historic Spaces as a Form of Intangible Cultural Heritage | Antiquity | Cambridge Core.” Antiquity 87 (336): 574–80. https://doi.org/doi:10.1017/S0003598X00049139.

Carpenter, Daniel. 2021. “Craft Skills under Threat with 27 Additions to the HCA Red List of Endangered Crafts.” Heritage Crafts. July 23, 2021. https://heritagecrafts.org.uk/craft-skills-under-threat-with-27-additions-to-the-hca-red-list-of-endangered-crafts/.

Centre, UNESCO World Heritage. 2021. “The World Heritage Convention.” UNESCO World Heritage Centre. 2021. http://whc.unesco.org/en/convention/.

“Charter on the Preservation of the Digital Heritage - UNESCO Digital Library.” 2009. UNESDOC Digital Library. 2009. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000179529.page=2.

“Defining Cultural Heritage and Cultural Property.” 2020. Blue Shield International. February 11, 2020. https://theblueshield.org/defining-cultural-heritage-and-cultural-property/.

“Domains of The Intangible Cultural Heritage in Thailand.” 2021. Intangible Cultural Heritage. 2021. http://ich.culture.go.th/index.php/en/home/ich-domains.

Fredrick, Jana. 2017. “Rome Wasn’t Built in a Day (Because They Didn’t Have 3D Printers).” AMT Lab @ CMU. October 2, 2017. https://amt-lab.org/blog/2017/9/rome-wasnt-built-in-a-day.

“How Many Languages Are Endangered?” 2019. Ethnologue. June 4, 2019. https://www.ethnologue.com/guides/how-many-languages-endangered.

“Identifying and Inventorying Intangible Cultural Heritage.” n.d. UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage. Accessed November 30, 2021. https://ich.unesco.org/doc/src/01856-EN.pdf.

“Intangible Heritage Register | Abu Dhabi Culture.” n.d. Abu Dhabi Culture. Accessed November 30, 2021. https://abudhabiculture.ae/en/heritage-records.

Mahfoodh, Hajar, and Shadiya Alhashmi. 2020. “Safeguarding Intangible Cultural Heritage through UNESCO Partnership.” In 2020 Second International Sustainability and Resilience Conference: Technology and Innovation in Building Designs(51154), 1–5. https://doi.org/10.1109/IEEECONF51154.2020.9319941.

“Preserving the Intangible: New Technology for the Visual Arts | AniAge Project | Results in Brief | H2020 | CORDIS | European Commission.” 2020. CORDIS | European Commission. August 24, 2020. https://cordis.europa.eu/article/id/421862-preserving-the-intangible-new-technology-for-the-visual-arts.

“Safeguarding Communities’ Living Heritage | United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization.” 2017. UNESCO. 2017. http://www.unesco.org/new/en/culture/resources/in-focus-articles/safeguarding-communities-living-heritage/.

Simons, Gary F. 2019. “Two Centuries of Spreading Language Loss.” Proceedings of the Linguistic Society of America 4 (1): 27–12. https://doi.org/10.3765/plsa.v4i1.4532.

“Tangible and Intangible Cultural Heritage (U.S. National Park Service).” 2016. National Park Service. February 29, 2016. https://www.nps.gov/articles/tangible-cultural-heritage.htm.

“UNESCO - Browse the Lists of Intangible Cultural Heritage and the Register of Good Safeguarding Practices.” 2020. UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage. 2020. https://ich.unesco.org/en/lists.

“UNESCO - Frequently Asked Questions.” n.d. UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage. Accessed November 30, 2021. https://ich.unesco.org/en/faq-00021.

“UNESCO - Intangible Heritage Domains in the 2003 Convention.” n.d. UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage. Accessed November 30, 2021. https://ich.unesco.org/en/intangible-heritage-domains-00052.

“UNESCO - Text of the Convention for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage.” n.d. UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage. Accessed November 30, 2021. https://ich.unesco.org/en/convention.

“UNESCO - The States Parties to the Convention for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage (2003).” 2020. UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage. July 27, 2020. https://ich.unesco.org/en/states-parties-00024.

“UNESCO - United States of America.” n.d. UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage. Accessed November 30, 2021. https://ich.unesco.org/en/state.

“UNESCO - What Is Intangible Cultural Heritage?” n.d. UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage. Accessed November 30, 2021. https://ich.unesco.org/en/what-is-intangible-heritage-00003.