“New technology should not be banned or condemned because of its potential misuse.”

This quote ironically is sourced from Michael Punke, Global Policy Head for Amazon’s cloud-computing division during his defense of Amazon selling facial recognition technology to law enforcement agencies back in 2019. As of June 2020, the company has announced a 1-year ban on police use of their facial recognition technology, Rekognition, in hopes that “the pause ‘might give Congress enough time to implement appropriate rules” (WIRED). Other tech giants have implemented similar bans, including Microsoft and IBM, who has abandoned the development of their facial recognition technology entirely. These decisions leave a large, difficult question in the laps of other industries that may be developing projects that utilize facial recognition technology. Are the perceived benefits of facial recognition worth the negative impacts it may have on marginalized groups and a population’s overall privacy?

Artists and Facial Recognition: Uses and Subversions

In the arts space, there has been varying responses to the potential uses and harms of facial recognition. On the positive end, artists such as Peter Shoukry have embraced how this technology can amplify an audience’s experience through interactivity with a piece. After starting out with paintings that utilize augmented reality (AR), Shoukry expanded into facial recognition with Spoken, a piece that mimics the expressions and emotions of its viewer (V Magazine). In an Instagram post announcing the piece, Shoukry explains the methodology behind his work, “Upon looking at the painting, the portrait will automatically recognize and map the viewer’s face with its built-in camera sensors. Once the viewer is identified the face of the portrait will emulate whatever face expression they make simultaneously” (Instagram).

Beyond the creation of art, facial recognition has been used to aid in research. For example, researchers in California plan to use this technology to analyze the faces in paintings and sculptures in order to allow art historians to have a greater understanding of who the art piece may represent. This work is said to be possible due to the software, “grabbing data about defining elements of faces from portraits and comparing them to known depictions” (BBC). These researchers also plan to analyze artwork done by varying artists of the same subject, in order to test which traits are the most accurately replicated. Such works include, “Dante, Brunelleschi, Lorenzo de' Medici, Henry VII and Anne Boleyn as well as … several portraits that are claimed to be depictions of Shakespeare and help resolve which most accurately captures the face of the playwright” (BBC).

Despite these projects that embrace facial recognition technology, there has been recognizable consumer backlash due to privacy worries. Google’s Art and Culture app was a subject of these issues once they included a feature in 2018 that used facial recognition to match individuals with paintings with similar facial features, pulling from a database containing 1,200 works of art. Due to the use of machine learning to identify the position of a person’s head and to recognize a face’s appearance, critics were skeptical about their faces being cataloged or used for further development of the algorithm. Even though Google says “that the selfies are not being used to train machine learning programs, build a database of faces or for any other purpose [and] will only store your photo for the time it takes to search for matches,” there is a concern that the app normalizes the collection of facial data and that the rules may change over time (The Washington Post). Such critics include Jeramie Scott, national security counsel at the Electronic Privacy Information Center. He states that, "The rise in the use of facial recognition by Google and other companies normalizes a privacy-invasive technology that lacks meaningful protections for users … Google may state now that photos from the app will not be used for any other purpose, but such statements mean little when Google can arbitrarily change this stance with little fear of any legal consequences” (The Washington Post).

Privacy focused artists have created means of avoiding facial detection by tricking the recognition algorithm. They are able to achieve this by using patterns that emulate features that the technology is looking to identify or by blocking out these features entirely. The latter strategy has been dubbed Computer Vision Dazzle (CVDazzle) by its creator Adam Harvey, who coined the idea as a student in NYU’s Interactive Telecommunications Program in response to Facebook introducing auto-tagging features to the platform. To describe the methodology behind CVDazzle, “Facial recognition algorithms look for certain patterns when they analyze images: patterns of light and dark in the cheekbones, or the way color is distributed on the nose bridge—a baseline amount of symmetry. These hallmarks all betray the uniqueness of a human visage. If you obstruct them, the algorithm can’t separate a face from any other swath of pixels” (The Atlantic). In order to create the illusion of an obstruction or lack of symmetry, hair can be styled in front of the eyes while makeup applied in differing hues and shapes can disrupt the patterns that an algorithm is programmed to find.

Image 1: CVDazzle styles sourced from Adam Harvey's book. Source: The Atlantic.

However, this method is imperfect and can be difficult to implement correctly. During a test of this strategy, Atlantic columnist Robinson Mayer described his experience and takeaways, “Black and white face paint seemed to confound the programs better than blue and white paint did, perhaps because it was darker. Bangs had to not just drape but dangle, so as to hide the nose bridge and at least one eye. Using the facial recognition algorithm in my iPhone as a guide—in camera mode, it imposes a yellow box over whatever it thinks is a face—I successfully camouflaged my face only three of the five times I tried it. When I had a beard, I never succeeded” (The Atlantic). Despite these flaws, CVDazzle has been used as a form of protest when public organizations implement facial recognition surveillance technology. This has recently come to light in the UK where “Facial recognition cameras were rolled out by the Metropolitan Police for the first time in early 2020 and have been trialed in other places around the UK” (BBC). A “Dazzle Club” surfaced and began to walk the streets on a monthly basis while wearing CVDazzle-styled face paint. After the rise of COVID, these events have been moved to digital platforms with “live stream[s[ of readings, songs and discussion” (BBC).

In the case of creating patterns that trick algorithms with false positives, artists have found ways to design patterns similar to what facial recognition technology looks for, printing them on clothing items for people to wear. Adam Harvey also has a hand in this form of detection prevention through HyperFace. “The project, a collaboration with interaction studio Hyphen-Labs, features various patterns that are designed to trick facial recognition software into thinking it's seeing eyes, mouths, and the components of a face … used to fool the software—software used by the likes of Facebook and retailers—by having it focus on "its face," rather than yours” (Vice). The thought process of this strategy is rooted in the difficulty in avoiding detection. According to Harvey, “Instead of seeking computer vision anonymity through minimizing the confidence score of a true face (i.e. CV Dazzle), HyperFace offers a higher confidence score for a nearby false face by exploiting a common algorithmic preference for the highest confidence facial region. In other words, if a computer vision algorithm is expecting a face, give it what it wants” (Vice). These designs have been used by protesters in Hong Kong and for the BLM movement.

Image 2: Adam Harvey's HyperFace Prototype Design. Source: Vice.

Beyond artistic designs being used to functionally avoid detection by facial recognition software, works of art have also been created to avoid detection on an aesthetic level. In the case of Nonfacial Portraits, an exhibit being displayed in the Seoul Museum of Art, 10 paintings based off a single photograph are all unable to be detected by facial recognition algorithms. In order to achieve this, during the creation of each painting, artists “rigged up a camera with three facial recognition algorithms wherever each painter would be working. As the artists worked, the camera searched for faces and a monitor let the artist know if it found any, guiding the work so that the final product would be invisible to all three algorithms” (FastCompany).

Image 3: Picture of the workspace used by artists that contributed to the exhibit. Source: FastCompany.

How Flaws in Facial Recognition Can Lead to Inaccurate Results

Throughout the general population, the root of conflicted feelings about facial recognition technology stem from its perceived and documented impacts on privacy and inaccuracies within the algorithm. A Georgetown study estimates that over half of Americans have their faces recorded in police databases as of 2019 (Business Insider). The use of this data can have disproportionate effects on differing demographic populations. According to the Association for Computing Machinery (made up of 100,000+ students and professionals), “The technology too often produces results demonstrating clear bias based on ethnic, racial, gender, and other human characteristics recognizable by computer systems. The consequences of such bias … frequently can and do extend well beyond inconvenience to profound injury, particularly to the lives, livelihoods and fundamental rights of individuals in specific demographic groups” (The Association for Computing Machinery).

This statement is supported by evidence sourced from a study done by the National Institute for Standards and Technology (NIST), which identifies biases in facial recognition technology algorithms. It found that “Asian and African American people were up to 100 times more likely to be misidentified than white men, depending on the particular algorithm and type of search. Native Americans had the highest false-positive rate of all ethnicities, according to the study, which found that systems varied widely in their accuracy” (Washington Post). When looking at these biases, false positives (identifying an incorrect face as a correct match) are much more problematic than false negatives (identifying a correct face as an incorrect match), particularly in law enforcement scenarios. As discovered, “The faces of African American women were falsely identified more often in the kinds of searches used by police investigators where an image is compared to thousands or millions of others in hopes of identifying a suspect” (Washington Post). As such, POC, particularly women, are most likely to be false accused of crimes that they haven’t committed.

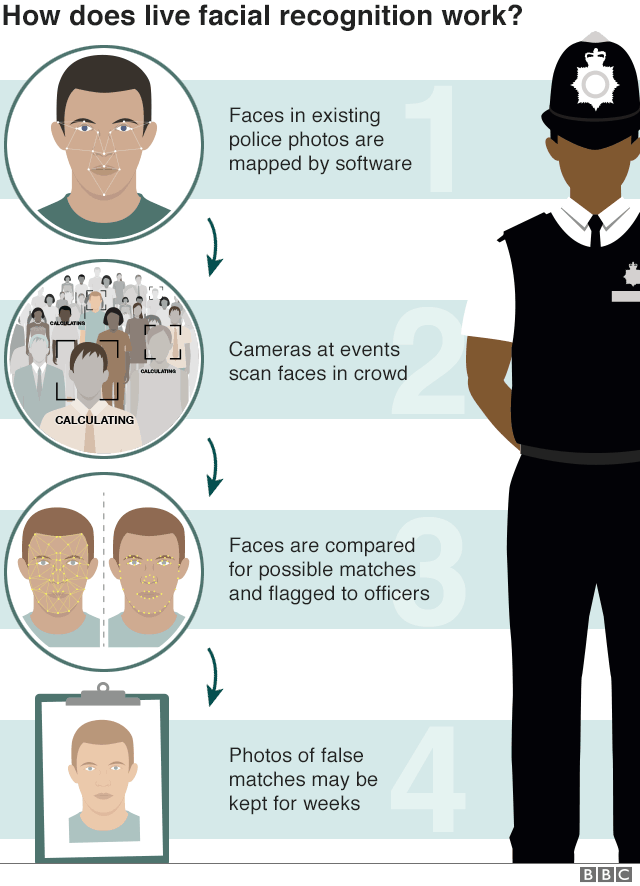

Image 4: An Explanation of How Facial Recognition Can be Used by Law Enforcement. Source: BBC.

In response, some cities have banned the use of facial recognition technology altogether, with Boston being the most recent. After San Francisco, Boston is the 2nd largest city to make this decision (Business Insider). This ban was enacted after a unanimous vote, and restricts city employees from using facial recognition technology, or from hiring 3rd party organizations in their stead. The inclusion of 3rd party contributions prove to be an important step, as facial recognition isn’t often used on body/dash cam footage, rather being used on footage sourced from cameras owned by outside sources. This decision was the product of various issues, with Boston City Counselor Ricardo Arroyo reasoning that “As communities are demanding real change from their elected officials, we need to proactively ensure that we do not invest in technology that studies show is ineffective and furthers systemic racism” (The Boston Globe).

Image 5: A Breakdown of Facial Recognition Acceptance by Demographic. Source: Pew Research Center.

Facial Recognition’s Effectiveness May See Decline Due to Face Coverings

The recent adoption of facemasks/coverings in light of the COVID pandemic has began to change the landscape of facial recognition technology, as different mask styles obstruct different aspects of a person’s face. “Facial-recognition experts say that algorithms are generally less accurate when a face is obscured, whether by an obstacle, a camera angle, or a mask, because there’s less information available to make comparisons” (WIRED). The degree of this difficulty can differ due to a number of factors, such as the size of a database that images are being stored, with smaller collections seeing less of an impact than larger collections. According to Alexander Khanin, CEO and cofounder of VisionLabs, a startup in Amsterdam, “When you have fewer than 100,000 people in the database, you will not feel the difference. With 1 million people, accuracy will be noticeably reduced and the system may need adjustment” (WIRED). This means that smaller firms using facial recognition technology will have a lesser impact on their software’s accuracy than a larger firm would.

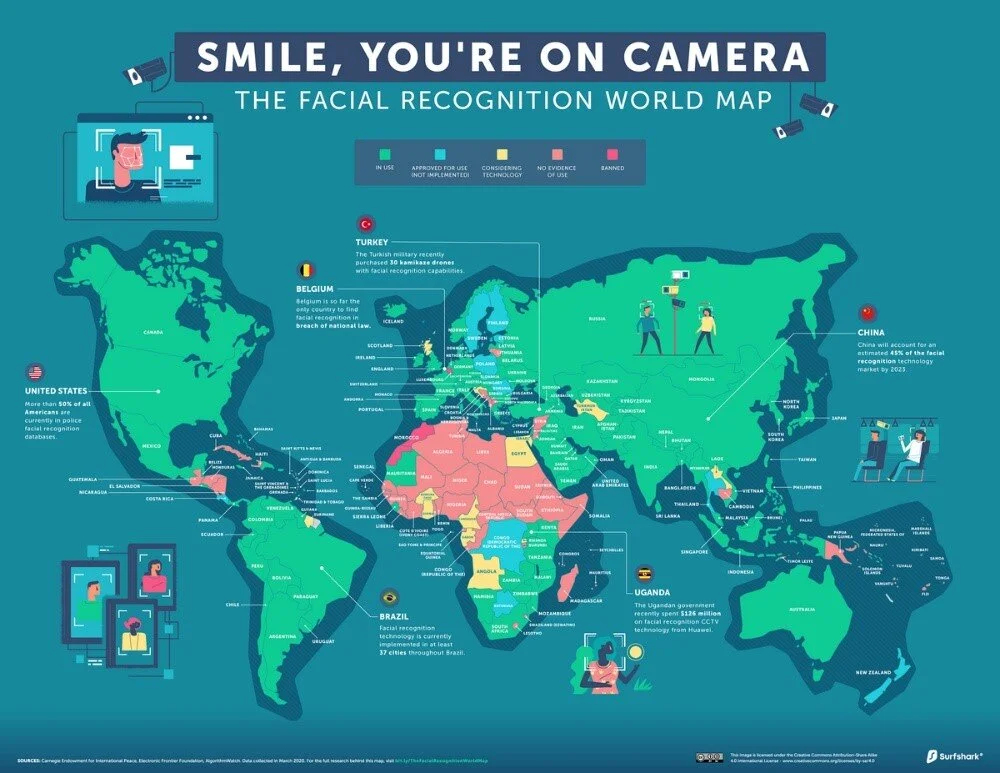

Image 6: Graphic Displaying Worldwide Usage of Facial Recognition. Source: VisualCapitalist.

The degree of privacy laws and public surveillance also have an impact on a software’s accuracy prior to COVID, with both Russia and China scoring high on both accounts. “Lighter privacy rules and wider acceptance of surveillance make it easier for those companies to gather the data and operational experience needed to improve facial-recognition algorithms” (WIRED). However, the drawback of these claims are accusations of human rights violations, particularly in China. A selection of Chinese facial recognition companies were restricted in the United States due to “allegedly supplying technology used to oppress Uighur Muslims in China’s northwest” (WIRED}.

In response to changes in accuracy being a matter of various factors, the National Institute of Standards and Technology tested various algorithms, using a database of 6 million photos, digitally adding different mask styles to each for 1-to-1 testing. As a result, “Even the best of the 89 commercial facial recognition algorithms tested had error rates between 5% and 50% in matching digitally applied face masks with photos of the same person without a mask” (NIST). Across the board, overall accuracy was reduced, the more a nose was covered the less accurate a reading, and false negatives increased (NIST).

Image 7: Example of How Photos were Altered to Test Algorithmic Accuracy. Source: NIST.

Despite these issues with accuracy, some companies are still planning to use facial recognition technology in the wake of COVID. This is most prevalent in the sports industry, where “use of facial-recognition technology may allow sports venues to bring back small numbers of fans – most likely season-ticket holders or VIP guests” (Fox News). The reasoning behind this idea is to help ensure a contactless entry to a stadium, without the need to scan a ticket or ID. Plans are in place to have turnstile cameras “measure the fan’s temperature, with a second camera confirming that the person is wearing a facemask. The fan would then show his or her face so the camera can verify identity” (Fox News). This method may also be implemented by other event-oriented venues such as movie theatres, live theatre, etc.

Image 8: Example of Thermal Cameras Being used in Adjunction to Facial Recognition Tech. Source: CNN.

The need for this service and the recent economic downturn has prompted companies outside of the tech sphere to bring facial recognition into their product mix. Silco Fire and Security, which started out as a typical home security company that ventured into facial recognition. After marketing the new services in April, Silco Fire and Security “has provided it to museums including the Cleveland Museum of Art and the Cleveland Museum of Natural History, as well as schools, daycare centers, a bakery, a church, the Union County courthouse, and manufacturing facilities” (GovTech). The inclusion of art-based organizations shows that there is a demand for facial recognition technology in the industry, despite the pandemic and potential flaws.

Should Arts Institutions Invest in Facial Recognition Technology

There is no definitive yes or no to the question of whether to invest in this technology or not, as the answer depends on how differing factors impact an organization:

1. Funding: With the examples of private companies restricting their facial recognition technology to certain organizations and select cities banning their employees from using the technology, an arts manager needs to consider how their organization receives funds. On top of this issue, the controversial nature of this technology could impact how audiences, investors, or donors view an organization with the technology in place. If the use of facial recognition in administrative or artistic fashions may lead to possible impacts on revenue, it is important to know the potential value the technology will bring to the table.

2. Accuracy: If an organization wishes to use facial recognition for admission or other customer relations services, understanding the degree of bias within the technology is vital. This importance is heightened when servicing populations with high rates of diversity. As stated before, POC and women are more likely to be misidentified by these algorithms, so the chances of error need to be addressed before such a system is put into place. If not, false positives could admit individuals into an event under another guest’s image. This is particularly problematic when events are ticketed, with each person having a pre-determined seat.

3. Transparency: As noted with the Google app example, individuals can be wary of partaking in facial recognition attractions or services due to privacy concerns. As a result, arts managers need to put into place a solid, secure transparency policy before the technology is implemented. Factors that need to be addressed are how images are stored, for how long, and who has access to them. For the full effect, consent agreements should also be considered in order to reinforce a transparent environment surrounding the creation, use, and storing of data.

For more content on facial recognition, check out some of our recent content on the subject:

https://amt-lab.org/blog/2020/2/what-makes-facial-recognition-controversial

https://amt-lab.org/blog/2020/1/image-recognition-technology-in-museums?rq=facial%20recognition

RESOURCES

Aitken, Peter. “Some Sports Teams Explore Facial-Recognition Tech, Hope It Will Help with Contactless Admission.” Fox News. FOX News Network, August 2, 2020. https://www.foxnews.com/us/sports-teams-facial-recognition-contactless-admission.

“Art Research Effort Aided by Face Recognition.” BBC News. BBC, June 6, 2013. https://www.bbc.com/news/technology-22764822.

Datta, Mansi. “The Future of Art Using Face Recognition Technology by American Model and Artist Peter Shoukry.” V Magazine, June 23, 2020. https://vmagazine.com/article/how-facial-recognition-technology-is-entering-the-art-world/.

DeCosta-Klipa, Nik. “Boston City Council Unanimously Passes Ban on Facial Recognition Technology.” Boston.com. The Boston Globe, June 24, 2020. https://www.boston.com/news/local-news/2020/06/24/boston-face-recognition-technology-ban.

“Facial Recognition: Artists Trying to Fool Cameras.” BBC News. BBC, March 18, 2020. https://www.bbc.com/news/av/uk-51913870/facial-recognition-artists-trying-to-fool-cameras?intlink_from_url=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.bbc.com%2Fnews%2Ftopics%2Fc12jd8v541gt%2Ffacial-recognition.

“George Floyd: Microsoft Bars Facial Recognition Sales to Police.” BBC News. BBC, June 11, 2020. https://www.bbc.com/news/business-53015468?intlink_from_url=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.bbc.com%2Fnews%2Ftopics%2Fc12jd8v541gt%2Ffacial-recognition.

Harwell, Drew. “Federal Study Confirms Racial Bias of Many Facial-Recognition Systems, Casts Doubt on Their Expanding Use.” The Washington Post. WP Company, December 19, 2019. https://www.washingtonpost.com/technology/2019/12/19/federal-study-confirms-racial-bias-many-facial-recognition-systems-casts-doubt-their-expanding-use/.

Hill, Kashmir. “Wrongfully Accused by an Algorithm.” The New York Times. The New York Times, June 24, 2020. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/06/24/technology/facial-recognition-arrest.html.

Holmes, Aaron. “Boston Just Became the Latest City to Ban Use of Facial Recognition Technology.” Business Insider. Business Insider, June 24, 2020. https://www.businessinsider.com/boston-bans-government-use-of-facial-recognition-technology-2020-6.

Holmes, Aaron. “These Clothes Use Outlandish Designs to Trick Facial Recognition Software into Thinking You're Not Human.” Business Insider. Business Insider, June 5, 2020. https://www.businessinsider.com/clothes-accessories-that-outsmart-facial-recognition-tech-2019-10.

Holmes, Kevin. These Colorful Patterns Trick Computer Facial Recognition to Fight Surveillance, January 5, 2017. https://www.vice.com/en_us/article/aen5pz/countersurveillance-textiles-trick-computer-vision-software.

“IBM Abandons 'Biased' Facial Recognition Tech.” British Broadcasting Company. BBC, June 9, 2020. https://www.bbc.com/news/technology-52978191?intlink_from_url=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.bbc.com%2Fnews%2Ftopics%2Fc12jd8v541gt%2Ffacial-recognition.

Matsakis, Louise. “Amazon Won't Let Police Use Its Facial-Recognition Tech for One Year.” Wired. Wired, June 10, 2020. https://www.wired.com/story/amazon-facial-recognition-police-one-year-ban-rekognition/.

Meyer, Robinson. “How I Hid From Facial Recognition Surveillance Systems.” The Atlantic. Atlantic Media Company, August 20, 2015. https://www.theatlantic.com/technology/archive/2014/07/makeup/374929/.

“NIST Launches Studies into Masks' Effect on Face Recognition Software.” NIST. NIST, August 4, 2020. https://www.nist.gov/news-events/news/2020/07/nist-launches-studies-masks-effect-face-recognition-software.

Schwab, Katharine. “These Portraits Were Painted to Confuse Facial Recognition AI.” Fast Company. Fast Company, July 9, 2019. https://www.fastcompany.com/90246732/10-artists-painted-portraits-that-confuse-facial-recognition-ai.

Shaban, Hamza. “A Google App That Matches Your Face to Artwork Is Wildly Popular. It's Also Raising Privacy Concerns.” The Washington Post. WP Company, January 17, 2018. https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/the-switch/wp/2018/01/16/google-app-that-matches-your-face-to-artwork-is-wildly-popular-its-also-raising-privacy-concerns/.

Simonite, Tom. “How Well Can Algorithms Recognize Your Masked Face?” Wired. Conde Nast, May 1, 2020. https://www.wired.com/story/algorithms-recognize-masked-face/.

“STATEMENT ON PRINCIPLES AND PREREQUISITES FOR THE DEVELOPMENT, EVALUATION AND USE OF UNBIASED FACIAL RECOGNITION TECHNOLOGIES.” ACM U.S. Technology Policy Committee. The Association for Computing Machinery, June 30, 2020. https://www.acm.org/binaries/content/assets/public-policy/ustpc-facial-recognition-tech-statement.pdf.