When visiting a website, it is probably unlikely that the first thing you navigate to is the privacy policy. Often tucked away in the footer of the home page, it may seem like a less significant destination than the article you wanted to read or the purchase you intended to make. Privacy policies, however, include important information regarding these actions. With more attention going to personal data privacy with changing policies and high-profile cases, the presence and relevance of a website’s privacy policy is becoming increasingly important.

For nonprofit arts organizations, the need for a privacy policy may not be obvious since their websites receive fewer visitors and collect less personal data than sites such as Facebook. However, with rising consumer expectations regarding personal data privacy and recent policy updates, having a privacy policy can be just as important for nonprofit organizations as it is for for-profit entities. Since the relationships between nonprofit arts organizations and their patrons—who provide voluntary support, sometimes without getting anything in return—are largely built on trust, organizations’ transparency about how they use consumer data is vital for maintaining these relationships. Whether visitors are reading the privacy policy in depth or scrolling past it, having one accessible to users is important for showing that the organization cares about users’ privacy and security.

Yet, within a sample of nonprofit arts organizations, only 45% of institutions had a privacy policy of any sort. Only 41% had privacy policies written specifically for the organization’s website and data collection methods. This article will explain why including an easily accessible privacy policy is an effective step for arts organizations to take to increase consumer trust, whether the organization is abiding by an existing legislation or not. When put into practice, integrating a privacy policy into their websites allows organizations to plan the ways in which they will use the data they collect, protect themselves if a data breach occurs, and increase their trustworthiness.

Policies Requiring Privacy Policies

The article What Arts Nonprofits Should Know About Data Privacy And Security details two recently enacted data privacy policies—the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) and the California Consumer Privacy Act (CCPA)—that both include requirements for website privacy policies. For nonprofits located in the United States that collect personal identifiable information (PII) from EU residents, the GDPR, which went into effect in May 2018, requires the organization to comply with its policy or face a fine. GDPR considers PII to be “any information relating to an identified or identifiable natural person,” which can mean names, addresses, or emails. If a nonprofit organization is collecting this information, it must inform individuals of what data it is collecting, how the organization is using that data, and how the organization could remove or “forget” the data if the individual requests it. The GDPR also requires an element of actionable consent, meaning that visitors must check a box, for example, opting in—not out—for their data to be collected. The natural way for an organization to meet these requirements is through an accessible privacy policy on its website, including an opportunity for response.

While the CCPA—which went into effect in January 2020—does not apply directly to nonprofits, it also includes specific requirements regarding what companies should include in their privacy policies and how often they should be updated, if the company is collecting data from California residents. According to Nate Garhart with the firm Farella Braun + Martel, nonprofit arts organizations that could be held accountable by this act include any that control or are controlled by a for profit entity; operate under a brand name owned by for-profit entity; or any that enter a joint venture or contract with a for-profit company that would require compliance.

Purpose of Privacy Policies

Even if there is no overarching law requiring nonprofit arts organizations to have privacy policies, having one allows organizations to show that they are transparent and trustworthy, encourages them to plan ahead for how they will use and protect consumer data, and provides basic legal protection for the organization in the case of an issue with consumer data. According to research published by Pew Research Center in April 2020, half of U.S. citizens have decided not to use a product or service because of privacy concerns. For 21% of those respondents, the product/service that they identified was a website, making up the largest portion of forgone products/services. The most common concerns for Americans who felt that their privacy was at risk were requirements to share general personal information and the service generally being untrustworthy. Since many nonprofit arts organizations’ websites ask for personal information when signing up visitors for email newsletters or for completing donations or ticket purchases, they could be affected by this distrust. Additionally, if consumers think that a website is not trustworthy, it is possible for them to abandon it before even engaging with the organization. Having an accessible privacy policy would solve both of these issues since it would indicate to website visitors that the organization is thoughtful about its visitors’ privacy and would allow visitors to read about how the organization is using their information before providing it.

While the main purpose of privacy policies is to inform visitors of how their data is being collected and used, their existence also signals to visitors that the organization cares about their rights. According to the article When changing the look of privacy policies affects user trust: An experimental study, “visibility had the strongest influence on relevance.” In 1998, the Federal Trade Commission identified Fair Information Practice Principles (FIPPs), which have five dimensions: notice, choice, access, security, and enforcement. A study on privacy policies in the context of online banking published in 2018 in Government Information Quarterly found that while enforcement—or the indication that the company had a mechanism to keep information safe—had the strongest impact on the perceived effectiveness of privacy policies, access and notice had similarly significant effects. Access and notice have no relation to the content of the privacy policy; their significance indicates that consumers “value an organization's effort to inform them about its information practices and to allow them to make changes to personal data,” according to The role of privacy policy on consumers’ perceived privacy. Another study found that while 66% of respondents indicated increased confidence in the website if a privacy policy is present, only 54% indicated that they would read the privacy policy upon first visiting a website.

Methods

To determine how well nonprofit arts organizations are following privacy policy recommendations, I searched 100 arts nonprofits’ websites for accessible privacy policies. These arts organizations were selected from Americans for the Arts’ Arts Services Directory, which includes arts organizations from across the United States who have worked with or are members of Americans for the Arts. Organizations selected were classified as “Performing Arts” and “Museum/Gallery” since those sectors have the most patron interaction for ticket purchases, etc. To provide an even distribution of disciplines, I selected 50 performing arts organizations and 50 museums/nonprofit galleries.

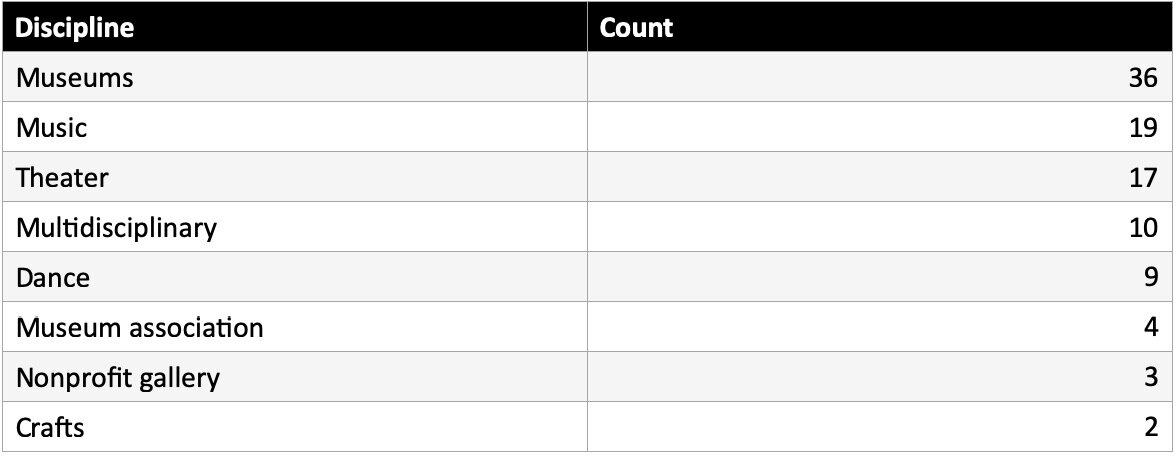

The final dataset includes 50 performing arts organizations and 50 visual arts organizations (including museums and nonprofit galleries). They are balanced from regions across the United States—as defined by the National Assembly of State Arts Agencies—but the largest percentage (28%) come from the Mid-Atlantic region. A variety of disciplines are represented from across the performing arts and visual arts sectors, as shown in Table 2 below. The largest area represented was museums, totaling 34 in the data set, but these covered a breadth of focuses, including Latin American and Native American art. For the 96 organizations that had accessible financial information, 2018 gross receipts ranged from $16,272 to $2,102,055,266 (excluding one outlier that had $0 of gross receipts). The average amount of gross receipts was $35,255,083 and the median amount was $2,116,953.

For an organization to be counted as having a privacy policy, it had to have a statement accessible on its website or a link to a third-party privacy policy such as the Google Privacy Policy or ReCAPTCHA protection. Some organizations’ policies were only accessible after searching the website or opening the page to buy a ticket or make a donation. While it is best practice to have the privacy policy linked in a footer that is visible on any page of the website then highlighted on the home or donation pages, I counted those policies that were buried in another page. Some organizations’ websites use third-party donation or email subscription services that include their own privacy policies. These were not counted since they did not apply to the whole website but were only applicable when a visitor was engaged in a transaction.

Table 1. Arts organization regions. Source: Author

Table 2. Arts organization disciplines. Source: Author

Results

Out of the 100 arts nonprofits included in this search, 55 do not have a privacy policy included on their website. Of the 45 websites that do include or link to a privacy policy governing website use, 41 have privacy policies written specifically for the organization’s website and its data collection, and four others link to applicable third-party policies.

privacy policies

Excluding the four organizations that did not have financial information, the ten organizations with the highest gross receipts all have privacy policies. Conversely, only two of the 15 organizations with the lowest gross receipts have privacy policies. When the included organizations are divided into thirds based on their gross receipts, 12.5% of the bottom third ($0-$860,000) have privacy policies, 50% of the middle third ($861,000-$4,400,000) have privacy policies, and 75% of the top third ($4,401,000-$2,200,000,000) have privacy policies.

Because important data privacy policies, including the GDPR and CCPA, have come into effect in the past two years, it is best practice for arts nonprofits’ privacy policies to be up-to-date. Of the 12 privacy policies that include the date they were last updated, only two have been updated since GDPR went into effect on May 25, 2018.

Discussion

With less than half of the nonprofit arts organizations studied having a privacy policy on their website and even fewer having a privacy policy that is specific to their organization, it is clear that implementing website privacy policies is an important next step for arts organizations improving their data privacy measures. This recommendation is relevant for arts organizations of any size, in any discipline, and across all regions of the United States. Even when dividing organizations by gross receipts, only 75% of the top third have privacy policies.

For nonprofit arts organizations, having a privacy policy seems to be correlated with having a significant amount of gross receipts. This could be because these arts organizations are larger and have more consumers, leading them to collect more data and take more measures to inform patrons about this data collection. Having more monetary resources could also lead organizations to put more attention into their privacy policies; high-grossing organizations would be more likely to have someone on staff to manage their website and have the resources to consult a lawyer about a privacy policy.

While it is best practice to consult a lawyer about writing a privacy policy, if an arts organization is small with no need for complicated policies and limited access to resources, it could use the privacy policy as a chance to be honest and straight forward with users about how their data is being collected and used. According to the Snell & Wilmer Cybersecurity and Data Privacy Law Blog, “The most important aspect of a privacy policy is that it [reflects] the company’s actual practices.” A simple statement ensuring users about the safety of their personal data is better than silence.

The balance between accessibility and content can be a dilemma for anyone adding a privacy policy to their website. Privacy policies can intimidate both readers and creators who expect long paragraphs of dense legal terminology. For a privacy policy to be most effective, however, high level diction is not necessary. According to the findings in The effect of online privacy policy on consumer privacy concern and trust, “The Privacy Policy is able to reduce privacy concerns only if consumers read and use the information contained in the policies. If the policy is not perceived as comprehensible then it is less likely to be reviewed by users. On the contrary, when consumers perceive that they can comprehend the Privacy Policy, they are more likely to read the policy and trust it.” Arts organizations considering adding privacy policies to their websites do not need to fear complicated language, but should use the policy as an opportunity inform users clearly and concisely about how the organization is protecting their information.

Because privacy policies are unique to how each organization collects and uses data, copying another website or using a template is not a good idea. Two privacy policies that I found in my search that would be good for inspiration, however, are from the Boston Symphony Orchestra and the Alvin Ailey Dance Company. When you first enter the BSO’s website, a banner pops up at the bottom of the screen informing the visitor that the site uses cookies; it also includes a link to the privacy policy. The Alvin Ailey website has a similar format: the home page also has a bottom banner that requires the user to click to agree to the use of cookies with an alternative to find out more information from the privacy policy. The sections of Alvin Ailey’s policy are similar to those of the BSO’s with the addition of information about security, a social media participation policy, and a link to the Ailey Shop’s privacy policy. For a more thorough comparison, see the chart below.

Table 3. Privacy policy comparison. Source: Author.

Conclusion

With the rising importance of having a website privacy policy and the high percentage of nonprofit arts organizations currently without one, nonprofit arts organizations should look into adding one to their websites. It is an easy way to increase user trust and is a solid first step in the changing data privacy landscape. While no laws currently require privacy policies on symphonies’ or museums’ websites, as more and more websites include them, users will expect the same from their trusted arts organizations.

Resources

Aïmeur, Esma, Oluwa Lawani & Kimiz Dalkir. “When changing the look of privacy policies affects user trust: An experimental study.” Computers in Human Behavior 58 (May 2016): 368-379. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2015.11.014.

Americans for the Arts. “Arts Services Directory.” https://secure.artsusa.org/eweb/DynamicPage.aspx?Site=AFTA&WebKey=98c5eb3b-023f-49af-9bba-d4bffd5ce584.

Bastide, Kelly Demarchis and Shannon K. Yavorsky. “Europe’s New Data Law: What Nonprofits Need To Know To Prepare For GDPR.” The Non-profit Times 32, no. 1 (February 2018): 15. http://link.gale.com/apps/doc/A531862275/AONE?u=cmu_main&sid=zotero&xid=e2a10f37.

Chang, Younghoon, Siew Fan Wong, Christian Fernando Libaque-Saenz & Hwansoo Lee. “The role of privacy policy on consumers’ perceived privacy.” Government Information Quarterly 35, no. 3 (September 2018): 445-459. https://doi-org.proxy.library.cmu.edu/10.1016/j.giq.2018.04.002.

Fowler, Patrick X. “Why You Need a Privacy Policy.” S&W Cybersecurity and Data Privacy Law Blog, March 10, 2015. http://www.swlaw.com/blog/data-security/2015/03/10/what-is-a-privacy-policy-part-1/.

Frankfurt, Tal. “What Does GDPR Mean For U.S.-Based Nonprofits?” Forbes, May 25, 2018. https://www.forbes.com/sites/forbestechcouncil/2018/05/25/what-does-gdpr-mean-for-u-s-based-nonprofits/.

Garhart, Nate. “Nonprofits and the California Consumer Privacy Act.” JD Supra, June 24, 2019. https://www.jdsupra.com/legalnews/nonprofits-and-the-california-consumer-24539/.

Gartner, Corinne and Kaitlyn Saberin. "Data Privacy and Protection Laws: Wading into the Alphabet Soup.” The Impact Foundry, December 13, 2019. https://impactfoundry.org/data-privacy-and-protection-laws-wading-into-the-alphabet-soup/.

"GDPR." In A Dictionary of the Internet, edited by Ince, Darrel. Oxford University Press, https://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/acref/9780191884276.001.0001/acref-9780191884276-e-4753.

"Good Practice: Fundraising - GDPR should You be Afraid?" Third Sector (May 2017): 42. https://search-proquest-com.proxy.library.cmu.edu/docview/1914194299?accountid=9902.

Hulshof-Schmidt, Robert. “State of Nonprofit Cybersecurity.” NTEN, 2018.

Janofsky, Adam. "Resource-Strapped Nonprofits Fight Cyberattacks from Governments and Hacktivists." WSJ Pro.Cyber Security (Jul 26, 2018). https://search-proquest-com.proxy.library.cmu.edu/docview/2171154435?accountid=9902.

Jehl, Laura and Alan Friel. "CCPA and GDPR Comparison Chart." Thomson Reuters, 2018. https://www.bakerlaw.com/webfiles/Privacy/2018/Articles/CCPA-GDPR-Chart.pdf.

Krass, Caroline, Jason N. Kleinwaks, Ahmed Baladi & Emmanuelle Bartoli. “The General Data Protection Regulation: A Primer for U.S.-Based Organizations That Handle EU Personal Data | Compliance and Enforcement.” Program on Corporate Compliance and Enforcement at NYU School of Law. https://wp.nyu.edu/compliance_enforcement/2017/12/11/the-general-data-protection-regulation-a-primer-for-u-s-based-organizations-that-handle-eu-personal-data/.

Lamanna, Kevin. “DIY PCI compliance: What nonprofits need to know to protect their donors.” NTEN Connect, March 14, 2018. https://www.nten.org/article/diy-pci-compliance-nonprofits-need-know/.

Laybats, Claire, and John Davies. “GDPR: Implementing the Regulations.” Business Information Review 35, no. 2 (June 2018): 81–83. doi:10.1177/0266382118777808.

Lehtiniemi, Tuukka and Jesse Haapoja. “Data agency at stake: MyData activism and alternative frames of equal participation.” New Media & Society 22, no.1 (January 1, 2020): 87-104. 10.1177/1461444819861955.

McCarthy, John. “Over 90% of users consent to GDPR requests says Quantcast after enabling 1bn of them.” The Drum, July 31, 2018. https://www.thedrum.com/news/2018/07/31/over-90-users-consent-gdpr-requests-says-quantcast-after-enabling-1bn-them.

Meyer, Catherine D., Fusae Nara & James R. Franco. “Countdown to CCPA #3: Updating your Privacy Policy.” Pillsbury Law, July 8, 2019. https://www.pillsburylaw.com/en/news-and-insights/ccpa-privacy-policy.html.

Micali, Mark. "AN UPDATE FOR NONPROFITS ABOUT FEDERAL PRIVACY LEGISLATION." NonProfit Pro 17, no. 3 (May 2019): 24. https://search-proquest-com.proxy.library.cmu.edu/docview/2246858036?accountid=9902.

Nouwens, Midas, Ilaria Liccardi, Michael Veale, David Karger, and Lalana Kagal. “Dark Patterns after the GDPR: Scraping Consent Pop-ups and Demonstrating their Influence.” Cornell University, January 8, 2020. https://arxiv.org/ct?url=https%3A%2F%2Fdx.doi.org%2F10.1145% 2F3313831.3376321&v=d078414d.

"Parsons Behle Lab Launches Automated Software That Generates Legal Documents to Comply with GDPR." PR Newswire, March 27, 2018. Gale Academic OneFile (accessed February 16, 2020). https://link-gale-com.proxy.library.cmu.edu/apps/doc/A532398427/AONE?u= cmu_main&sid=AONE&xid=a5895e64.

Perrin, Andrew. “Half of Americans have decided not to use a product or service because of privacy concerns.” Pew Research Center, April 14, 2020. https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2020/04/14/half-of-americans-have-decided-not-to-use-a-product-or-service-because-of-privacy-concerns/.

Pugliese, Anthony. "Privacy is a Priority." California CPA 88, no. 5 (2019): 4. https://search-proquest-com.proxy.library.cmu.edu/docview/2321818370?accountid=9902.

Sorrell, Karen L. “Cyber Attacks on Nonprofits: ONE DATA BREACH CAN COMPROMISE A CHARITABLE ORGANIZATION’S DONOR DATA AND PUT THE NONPROFIT OUT OF BUSINESS.” Property & Casualty 360 122, no. 1 (January 2018): 38–39. http://search.ebscohost.com.proxy.library.cmu.edu/login.aspx?direct=true&db=buh&AN=127972929&site=ehost-live.

"The Future of Data Justice Examines the Impact that Data Collection and Surveillance has on Marginalized Populations." Targeted News Service, Mar 25, 2019. https://search-proquest-com.proxy.library.cmu.edu/docview/2197343709?accountid=9902.

“The State of Data in the Nonprofit Sector.” EveryAction, Nonprofit Hub. http://cdn2.hubspot.net/hubfs/433841/The_State_of_Data_in_The_Nonprofit_Sector.pdf.

Thompson, Lisa. “Why Your Nonprofit Website Needs a Privacy Policy (And What to Include).” Nonprofit Hub, December 15, 2015. https://nonprofithub.org/nonprofit-web-design/nonprofit-website-needs-privacy-policy-include/.

Wells, Christina. “Why Nonprofits Need to Care About Proper Data Collection.” GuideStar Blog, April 2, 2018. https://trust.guidestar.org/why-nonprofits-need-to-care-about-proper-data-collection.

Winters, Paul and Jonathan Hwang. "THE CALIFORNIA CONSUMER PRIVACY ACT - WHAT NONPROFITS NEED TO KNOW." Taxation of Exempts 30, no. 7 (July 2019): 25-28. https://search-proquest-com.proxy.library.cmu.edu/docview/2260001317?accountid=9902.

Wu, Kuang-Wen, Shaio Yan Huang, David C. Yen & Irina Popova. “The effect of online privacy policy on consumer privacy concern and trust.” Computers in Human Behavior 28, no. 3 (May 2012): 889-897. https://doi-org.proxy.library.cmu.edu/10.1016/j.chb.2011.12.008.