Introduction

When considering the medium of livestreaming for organizational programming, one must be aware of its many advantages and challenges. Part one of this series looked at the historical context, artistic response, and general theory relating to livestreaming the performing arts. This second portion looks at two case studies. The first case study, The Geffen, set the precedent for non-Broadway theaters working with BroadwayHD. The second case study, The Orlando Shakespeare Theater, illustrates how a large regional theater can impact hundreds of classrooms with one performance, on a budget that is more feasible for regional theater companies.

Case Study 1 : The Geffen

As if influenced by O’Neill’s enthusiasm for televised reach, Long Day’s Journey Into Night began a modern journey to the screen on BroadwayHD in 2017. This journey started with a livestream, followed by a ten-day on-demand encore, and then an eternal life on BroadwayHD.

In “From Stage to Live Broadcasts and Streaming: O’Neill’s Theatre Guild Model in the Digital Age,” author Dan McGovern credits the collaboration between the Geffen Playhouse and BroadwayHD for artistic and commercial success. This livestream was not always so broad in scope. Initially, director Jeanie Hackett intended only to stream to Los Angeles schools in the absence of extended field trips (the play is, as it sounds by name, quite long). This was still the plan – when executive director Gil Cates, a man with a history in filmmaking, reached out to BroadwayHD.

Figure 1: Jane Kaczmarek and Alfred Molina as Mary and James Tyrone in Eugene O'Neill's Long Day's Journey Into Night. Source: Chris Whitaker.

Lee Seymour of Forbes believes the cost of livestreaming is prohibitively expensive, from 300 to 500 thousand dollars for an Off-Broadway multi-camera capture to up to $3 million on Broadway. The Geffen was able to underwrite this cost substantially, using what BroadwayHD co-founder Stewart Lane described as “the co-production model previously used with New York producers from Lincoln Center, the Roundabout Theatre Company, and the Public Theatre. The keys to this partnership included production selection, the right theatre, and the right connections between industry professionals.

This testimonial by Hackett illustrates what it looked like inside the theatre the evening of the capture and livestream, with six cameras (as opposed to Broadway shows’ fourteen): The BroadwayHD crew ultimately filmed one matinee and one evening performance of Long Day's Journey. They livestreamed the latter. "No discounts, no nothing," Hackett said; theatregoers "had already bought their tickets. I think both audiences were enlivened by the sense of an event going on." I asked Hackett whether the actors dialed down their performances for the screen. "No," she responded; "we told them not to. We said it is to be the exact same performance. I don't think any of them did that. I watched both shows." Modifying the performances was never an issue. "The actors are there with the audience," she explained; "there's no way you can serve two masters." This was consistent with BroadwayHD's general approach, said Lane: "What we're trying to capture is exactly what the theatre audience is seeing on the stage. I don't want the acting to change. I don't want the style to change. If you're playing to the second balcony, then play to the second balcony.

Backstage, a “crew of about forty people” managed screens as directed by performance-capture legend David Horn. Most regional theatres may not be able to support such a massive endeavor. Scaling down, however, does not mean a scaling back of audience reach, as evident in the next case study.

This case study provides a perspective of a large-scale regional theatre with the means to support a BroadwayHD-level production that costs many hundreds of thousands of dollars. The Geffen was the first of many regional theaters’ cooperation with BroadwayHD, and broke the mold for regional involvement. It provides context for production and what a smaller regional theatre’s dream-come-true may look like. However, the goals of regional theaters’ livestreaming efforts may fall underneath other mission goals, which will be explored in the second case study: The Orlando Shakespeare Theater.

Case Study 2: The Orlando Shakespeare Theatre as an Educational Model

Like The Geffen Playhouse, The Orlando Shakespeare Theatre saw potential in streaming plays into classrooms. However, instead of compensating for field trip visitation time, the “Shakes” sought to increase access to geographic areas that are too far away to conventionally reach. Currently, streams broadcast to Florida and Georgia counties (excluding their home of Orange County), and the program is looking to add Alabama or South Carolina to its lineup.

In an interview, Education Coordinator Brandon Yagel discussed how these livestreams started and what the organization has noticed in their development. Based on that conversation, here are some of the requirements and considerations you may need to take into account as a regional theatre to livestream your shows.

Figure 2: Terence Lee as Jack in Jack in the Beanstalk. Source: Orlando Weekly.

“The Play’s The Thing”

If you want to livestream, your playwright and their publisher will also want to livestream. The Orlando Shakes’ next livestreamed educational endeavor will be Interstellar Cinderella, a newer work like their recent iteration of Jack and the Beanstalk. They’ve also found massive success with tried and true works like The Jungle Book and Miss Nelson is Missing. Some shows in the lineup, however, are not permitted to be livestreamed; these tend to be big, recognizable titles. In this way, livestreaming tends to favor newer works.

What has been new and necessary for all of these livestreams is contractual writings. As a regional theatre, you will want to discuss how you will form livestream-related contracts with playwrights and publishers.

Figure 3: Ana Martinez Medina and Amanda Dayton in The Jungle Book. Source: Orlando Shakes.

That being said, when asked if there was any play he would personally choose to disseminate, Yagel emphasized the importance of the vehicle. “It’s less about which show we stream. If anything, I think streaming means that more people can watch more shows, more often. As opposed to one show a year, you might watch one show a week in your classroom! I think that’s the goal with every show.” In the schools where the Shakes streams, teachers report that it is the first interaction with live theatre for 65% of their students.

Nuts and Bolts

To stream to 53 Florida schools and 47 Georgia schools (nearly 360 classrooms in total), the Shakes employed a local company called Skystorm Productions, a full-service production agency with experience capturing sporting events, competitions (including the Call of Duty championships), concerts, debates, and so on. Yagel described their setup at the shakes as a “PBS-Quality setup” with multiple switching cameras, a satellite outside, and a live studio audience of school students. Cameras were pointed to capture the performance, but not shy away from capturing the students in the audience, creating a community feel for those watching remotely.

There were two livestreams, one at 9am and one at 1pm, hosted primarily on livestream.com (with a secret YouTube link ready to be sent out in case of host problems). Following performances, students were encouraged to engage with the cast via a live chat-based talkback.

The staff of the Shakes is dedicated to the livestream for the majority of the day. The program, originally spearheaded by the previous Executive Director, relies on a special front-of-house team, a responsive technical team, and in different ways, every member of cast, crew, and staff. Yagel mentioned the growing importance of marketing as the program attempts to expand. (It doesn’t hurt to mention here as well, that Yagel has experience as a web developer!)

Hosts with the Most

The Shakes developed contact lists of schools in Florida and Georgia. They contacted these schools, first via email and later via postcard, to invite them to participate in the livestreaming process. Included with the secure link to the livestream was access to student study guides, to provide the same experience offered to field trip visitors. Additionally, students were encouraged to send questions via chat features for a live talkback after the performance.

Speaking of schools, there are challenges on the other end of the stream. “Schools don’t always have the best Wi-Fi capabilities in the world,” said Yagel. He discussed how some schools benefit from gathering students in the auditorium, while others have the same stream across multiple classrooms. While he troubleshoots from his end in the Shakes, some problems can only be solved on the other end of the line.

It’s proven to be worth every bump in the road. In a reflection of the previous section discussing ticketing and broad reach, Yagel mentioned the power of livestreaming. “It’s a whole different world to impact so many students. We can double the numbers of students we see over a course of a month of field trips, in one effort.” Their most recent stream, Miss Nelson is Missing, reached about 14,000 students. The Orlando Shakespeare Theater’s Margeson Theatre seats 324.

Redundancy & Support

One extremely important consideration Yagel stressed was redundancy. “Someone always says, ‘this has never broken down,’” reflects Yagel, who saw the morning production of the Jungle Book go down with Livestream.com. Yagel makes sure that a secret YouTube livestream is queued up in an email if the main streaming platform ever crashes in this way. During a show, Yagel is in a conference room HQ with its own monitor where he fields e-mails, troubleshoots for teachers across the Southeast, and moderates comments in the talkback. An outgoing stream only takes 10GB, according to Livestream’s site, and the Shakes makes sure it has 30GB to keep the stream going strong. Wifi is never the weakest link, as multiple ethernet cables are set up as contingency.

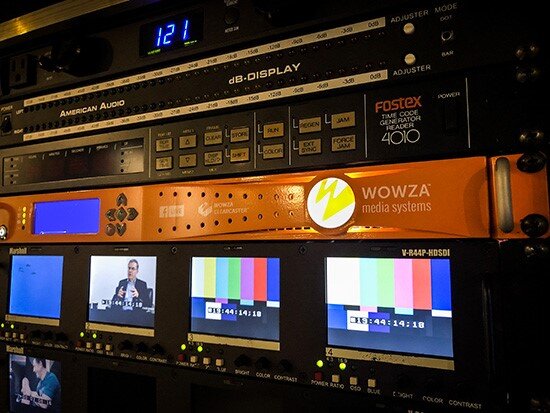

Figure 4: Some of Skystorm Production’s livestreaming equipment. Source: Skystorm Productions.

The project was supported by a $10,000 grant from the Orlando Magic Youth Foundation, from whom the Orlando Shakespeare Theatre received a total of $30,000 in 2019.

The Next Step

Yagel sees a not-so-distant future where teaching artist workshops are offered on this same broad scale. The Shakes’ “Shakespeare Live” programming for middle schools and high schools, and “Books Alive” for elementary schools, may soon see the same digital treatment – a digital version of the lessons, recorded with three cameras, delivered with a set of videos and physical materials for teachers to use in their classrooms.

Other Considerations

The group producing Long Day’s Journey at the Geffen believe in streaming to large screens, inviting a “communal” experience. Cates, especially, believes that capture for later viewing has the most potential for commercial success and longevity. The Shakes’ production of Jack and the Beanstalk was preserved online for one week following the performance. While livestreaming succeeds with big names and excitement, captures can become a part of ongoing conversation.

Capture comes with a myriad of contractual hurdles. Not only does capture affect your artists via SAG and AFTRA requirements, it affects the rights of your work, content hosting, and content distributing. Capture may very well be more prohibitively expensive and involved than any kind of live stream, dominated by the biggest players.

Conclusion

Both of these theaters provide a perspective of what it means to livestream. The Geffen’s ability to support BroadwayHD allows us to take a look at best practices for livestreaming on a large scale, while the Shakes shows how large scale livestreaming is just as feasible without involvement with industrial-sized organizations. No matter your size or budgeting restraints, livestreaming can reach more audience members than your theater can hold. It is possible to experience the perfect storm of resources, staff capacity, and an understanding of what can be streamed and to whom.

Some big names in theatre management are not fond of the idea of livestreaming. Dan McGovern cites two major concerns about streaming; cannibalizing audiences for a run by livestreaming too early, and cannibalizing a potential tour. (96) More worries were expressed by executive director of the Dramatists guild, Ralph Sevush, who cited movie deals, royalty cannibalization, and piracy as three additional dangers. (97) Michael Kaiser himself fears that regional theatres leaning into digital distribution will become risk-averse and abandon live performance in general. (99) Brandon Yagel, however, assuaged these fears by citing the spirit of Star Trek: The Next Generation.

“There are a number of episodes where – especially with Patrick Stewart – the crew put on Shakespeare plays in their holodeck. I feel like with every manner of technology, that kind of progress is inevitable.”

Resources

“About Us.” National Theatre Live, ntlive.nationaltheatre.org.uk/about-us.

Ates, Alex. “Netflix Sets the Stage: THE STREAMER’S PRODUCTION OF BROADWAY’S ‘AMERICAN SON’ SIGNALS A GROWING INTEREST IN THEATER FOR THE SMALL SCREEN.(THEATER).” Back Stage, National ed. 60, no. 7 (February 14, 2019).

Barone, Joshua. “Audible Creates $5 Million Fund for Emerging Playwrights.” The New York Times, The New York Times, 30 May 2017, www.nytimes.com/2017/05/30/theater/audible-creates-5-million-dollar-fund-for-emerging-playwrights.html.

Blake, Bill. Theatre & the Digital Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire ;: Palgrave Macmillan, 2014.

“BroadwayHD Unveils On-Demand Streaming Service for Theatrical Productions.” Wireless News (October 31, 2015).

Brook, Peter. The Empty Space. Penguin Books, 2008.

Chuang, Tamara. “If Edward Snowden Starts Talking to You on the Big Screen, You Know This Isn't a Regular Movie.” The Denver Post, The Denver Post, 19 Aug. 2016, www.denverpost.com/2016/08/17/fathom-events-movie-theater-denver-colorado/.

Schwartz, Jonas. “Long Day's Journey Into Night.” TheaterMania, February 14, 2017. https://www.theatermania.com/los-angeles-theater/reviews/long-days-journey-into-night-geffen-playhouse_80040.html.

Halterman, Jim. “The Freedom of Streaming.” Back Stage - National Edition 57, no. 25 (June 23, 2016): 6–6. http://search.proquest.com/docview/1841018606/.

Hillman-McCord, Jessica . iBroadway : Musical Theatre in the Digital Age Cham, Switzerland: Palgrave Macmillan, 2017.

James Steichen, HD Opera: A Love/Hate Story, The Opera Quarterly, Volume 27, Issue 4, autumn 2011, Pages 443–459, https://doi.org/10.1093/oq/kbs030

Kennedy, Mark. “Technology Is Remaking How We See the Ancient Art of Theater.” AP NEWS, Associated Press, 23 Oct. 2019, apnews.com/f717d2b1105d47339f5738ce60306595.

Lapin, Andrew. “Netflix's 'American Son' Adaptation Exposes The Play's Flaws.” NPR, NPR, 31 Oct. 2019, www.npr.org/2019/10/31/773444387/netflixs-american-son-adaptation-exposes-the-play-s-flaws.

Lindsay, Benjamin. “Theater to the People: For New Internet Streaming Service broadwayHD, the Only Way Is Up.” Back Stage, National ed. 57, no. 6 (February 11, 2016).

Mcgovern, Dan. “From Stage to Live Broadcasts and Streaming: O’Neill’s Theatre Guild Model in the Digital Age.” Eugene O’Neill Review 40, no. 1 (2019): 87–102. https://muse.jhu.edu/article/732830.

“Metropolitan Opera to Offer Hi-Def Simulcasts in NYC Public Schools.” Playbill, PLAYBILL INC., 12 Dec. 2007, www.playbill.com/news/article/7484.html.

Moon, Clarissa. “Livestream of Orlando Shakes Children's Production Reaches Thousands of Students Statewide.” Orlando Weekly. Orlando Weekly, June 3, 2019. https://www.orlandoweekly.com/Blogs/archives/2019/05/22/livestream-of-orlando-shakes-childrens-production-reaches-thousands-of-students-statewide.

“Orlando Video Production Company.” Skystorm Productions, skystorm.com/.

Radulovic, Petrana. “Where the Stars of Harry Potter's Fan-Generated Golden Age Are Today.” Polygon. Polygon, August 17, 2018. https://www.polygon.com/2018/8/17/17705568/harry-potter-fan-fiction-musical-puppet-pals-creators.

Schütz, Chantal, and Schütz, Chantal. “Globe on Video: From the ‘recording Angel’ to ‘High Definition and True Surround Sound.’” Coup de théâtre 31 (January 2017): 39–60.

“The Jungle Book.” Orlando Shakes, February 26, 2019. https://www.orlandoshakes.org/show/the-jungle-book/.