Digital technology is becoming a standard tool for the collection, preservation, and dissemination efforts of arts and cultural heritage worldwide. From 3D configuration of ancient artifacts to applying artificial intelligence to shed new light on how we perceive the lineage of humanities, cultural heritage is headed toward a digital future. This article will examine the ways in which digitization and artificial intelligence – two of the most widely used or relevant forms of technology in cultural heritage – are applied through global cases of innovative initiatives happening in the field in recent years.

DIGITIZATION

Only 15 percent of the world’s cultural heritage is currently available in a digitalized format. Regardless of how well they have been protected and preserved, a great majority of ancient artifacts and sites are naturally prone to corrosion due to age. In addition, there are incidents of unexpected natural and manmade calamity, as in the recent cases of fire that engulfed the 200-year-old National Museum of Brazil and its collection and the UNESCO World Heritage Site Notre Dame Cathedral in France. Once a heritage site is lost, damaged, or destroyed, the restoration process is slow, if possible at all. Other barriers can come along the way as in the reconstruction of Rani Pokhari in Nepal in 2015, where the contractors were found guilty of using cement over traditional material to minimize the cost. Not only is this unjust to the culture and history that has been embodied in the heritage for thousands of years, but it puts the site at greater risk if another disastrous situation ever occurs.

In the wake of such calamities, there has been a growing voice and movement to digitize cultural heritage to preserve them in the face of potential hazards such as climate change, natural disaster, poor policy or inadequate infrastructure. In addition to transferring physical objects to a safer repository, the Library of Congress has started to digitize its collection of sound and video recordings from the early 20th century at the Audio-Visual Conservation Center. The Smithsonian has also been actively digitizing its collection since 2013 with the release of the “Smithsonian X 3D Explorer,” allowing audiences to engage with the digitized versions of the museum’s 137 million artifacts, of which only two percent are on display. Although there are rapid developments in technologies that can increase the longevity of cultural heritage, the process of repositioning each artifact for 3D scans is extremely time-consuming. Even large institutions—as in the case of the Smithsonian—struggle.

The development of Germany’s CultLab3D has changed the digitization process through accelerated, automatic, multi-dimensional analysis utilizing multiple cameras and ultrasounds in their scanning process. CultLab3D’s 3D scanning technology captures various objects by combining data gathered on geometry, texture, and material properties to the micrometer level. The artifact being scanned is placed on a conveyor belt and goes through the automated process, where it is analyzed through “scanning arcs” and before “robotic arms” fill in missing parts.

The lab’s innovation lies in its speed – taking only five minutes to produce a digital copy of an object. It facilitates digital visualizations of physical artifacts and allows greater ease in archiving. The secret behind its ability to create immaculate scans lies in the multiple cameras installed in the laser scanner that captures the object from multiple angles. The different levels of scanning technology and features in the respective equipment is what enhances its ability to produce detailed digital reconfiguration of cultural objects regardless of their size or shape. As of now, CultLab3D provides scans through the use of CultLab3D, CultArm3D, CultArc3D, Meso-Scanner V1, Meso-Scanner V2, HDR-ABDF-Scanner, or individual lasers and photogrammetry setups depending on whether the size of the artifact is small or colossal like some architectural structures.

In addition to attaining visual precision of the digitalization process, CultLab3D’s scanning procedure incorporates an ultrasound to examine for unstable or damaged areas. This detail, in addition to higher efficiency powered by an accelerated scanning process, allows the assessment of overall health of the cultural artifact and captures the smallest features of the original piece that could be used in future preservation efforts.

Figure 1: Digitization in Cultural Heritage. Source: CultLab3D, Library of Congress, Smithsonian.

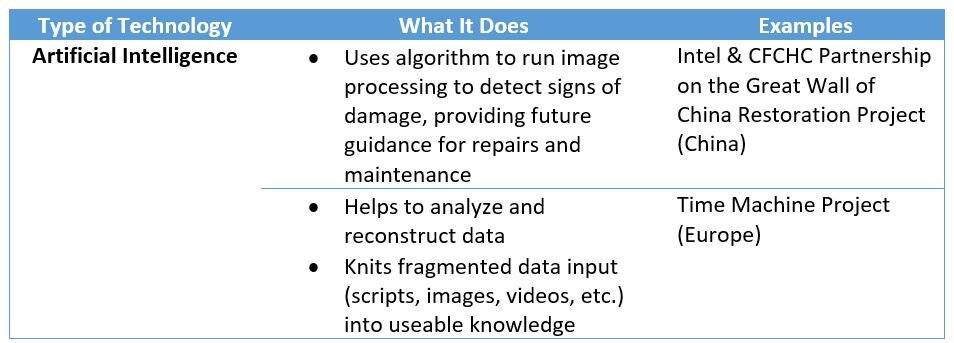

ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE (AI)

AI is another useful tool for preserving ancient human ingenuities from natural conditions and human activities. It can help to facilitate a more rapid process of tracking a cultural heritage’s lifespan and the type of measures that should be taken to guarantee its existence into the future.

A more advanced version of a 3D modeling application was powered by drones and artificial intelligence during last year’s partnership between Intel and the China Foundation for Cultural Heritage Conservation (CFCHC) joined by Wuhan University’s Laboratory of Information Engineering in Surveying, Mapping and Remote Sensing (LIESMARS), on preservation of the Great Wall of China. One of the key areas for examination included the Jiankou trail, known as one of the most scenic parts of the Wall and the most dangerous due to its steep terrain shrouded with trees. This project incurred heavy investment in time and human capital before drone technology and artificial intelligence were introduced. Traditionally, examinations would be performed over the span of several months, where the majority of the data was collected through visual inspection or manual tape measure from inspection teams risking potential danger as they pass heavily damaged trails along the Wall that stretches out to more than 13,000 mile in northern China.

The introduction of cutting-edge technology created a safer, more efficient method. Intel provided the Intel Falcon 8+ system, a line of commercial drones that feature superior flight performance and high accuracy in capturing reliable, high resolution aerial data of over 10,000 images to collect data to assess the damage on this centuries old UNESCO heritage site. The plan was for these drones to inspect the wall for signs of existing and potential deterioration. The Great Wall has shown signs of deterioration due to natural conditions and human damage, and experts have warned of potential precarious situations that will cause the site to incur even greater danger if no action is taken. The captured aerial data helped the researchers to develop a highly accurate 3D model of the wall to assess the level of damages and restoration efforts without the difficulties faced by traditional methods. A digital restoration plan of the wall was created pointing out specific areas calling for repair, maintenance, cost, and materials that will be needed in the restoration process.

The European Commission’s Time Machine Project is another attempt to analyze big data by drawing on the analytical power of artificial intelligence. In March of 2019 the European Commission proposed a mass scale research initiative to provide insight into the history and heritage of Europe. €1,000,000 in funding has been granted to the project and over 200 organizations from 33 European countries including national libraries, state archives, museums, academic and research institutes, private firms and governmental bodies are participating by providing massive amounts of data detailing thousands of years of Europe’s past. The final result will be a computer-generated simulation of the comprehensive social, economic, political, cultural, and geographical history of Europe. The AI used for Time Machine is trained to collect and analyze data from a wide temporal and geographical area. It will identify and tie together documents, artifacts, monuments, and other forms of fragmented historical datasets according to their similarities. The resulting data will not only provide access to a more diverse narrative of European past for the public and help individual researchers and institutes by taking the potential of research capacity to a completely different level, but also foster collaboration among different European nations in developing strategic planning to tackle environmental protection, sustainability, social welfare, immigration, and other pan-European challenges of today.

Figure 2: Artificial Intelligence in Cultural Heritage. Source: Intel, Time Machine Project.

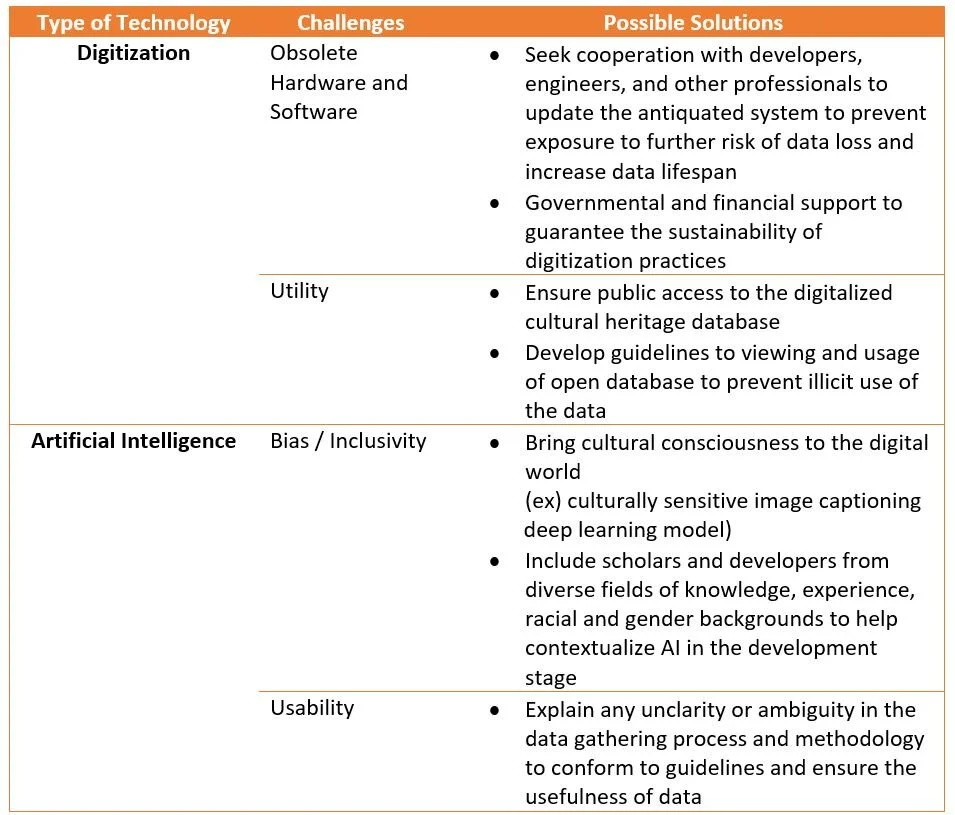

CHALLENGES

The data-driven reformation of cultural heritage practices entails several challenges. One of the obstacles preventing wider application of digitization technology to cultural heritage is the lack of updates in the hardware and software used by many organizations in the field. Outdated technology prevalent in organizations is a high expense for a low productivity and ROI. The 2009 UNESCO Charter on the Preservation of Digital Heritage calls attention to the need for partnerships so that the organizations will be provided with sufficient technical expertise that will help overcome the technology divide. Refurbishing the outdated systems would not only contribute to more efficient processing, tracking, and archiving of digital heritage, but also to the sustainability of data by limiting potential loss due to technical failure in obsolete systems. It is also important to note that in order for these renovations to take place, there needs to be a steady governmental and financial support for sustainability of such practices as they require continuous monitoring of infrastructure, safeguarding of digital contents, which inevitably incur long-term costs, exposing organizations to the risk of discontinuing digitization due to insufficient funding or budget.

Another consideration of a more digital landscape is ensuring the accessibility and usability of the digitalized data. Many institutions – like the Smithsonian – make their digitized collections open to all for viewing, but there are still many that lack visibility and limit access to the scanned data to the institution or authorized personnel only. Recently the Egyptian Museum in Germany was sued by an artist because of their policy of withholding the 3D scanned bust of Nefertiti from public access. The same artist is planning to continue to demand other renowned museums worldwide to make their data accessible. Most recently the artist filed a lawsuit against the Rodin Museum in France, to which the French government responded that “The Rodin Museum’s scans serve the mission of public service, and in principle, should be made accessible for both research and commercial exploitations.”

It is important to consider how bias in AI can affect the data collected in digital heritage. Cultivating the “cultural intelligence of AI” is vital when confronting the ethical issues ensuing innate bias of the AI system. The big data provided by current AI is heavily geared towards a male, western-centric point of view and largely misses out on the global voice, as they have been omitted from the system’s development process. IVOW is one platform trying to overcome this bias and introduce more inclusive storytelling in AI. Their “culturally sensitive image captioning Deep Learning Model,” for instance, helps identify images of certain demographic characteristics (race, ethnicity, gender, sexual orientation, etc.) with sensible tags and captions. The efforts to bring culturally adaptive AI will include considerations of different experiences to build a more culturally diverse narrative of the world’s heritage.

In addition, acknowledging the rules and assessing the confines and opportunities of this new digitalized form should be set as a standard practice in the field. The Venice Time Machine Project came to a halt in October and presented new challenges for the digital future in cultural heritage. The project started out in 2013 as a predecessor of the pan-European Time Machine Project and was suspended due to a disagreement between the two partnering organizations--EPFL and the State Archive of Venice--regarding the utility of the data gathered from 190,000 sources over the last five years. EPFL claims that the data collection process for the project had not abided by the “archival-science guidelines,” resulting in 8 terabytes of “useless” data missing the metadata that includes information on provenance of each source material used. The previous director of the State Archive argues otherwise, that the data is still scientifically valid and that missing metadata can be added on. Such instances reveal how the mutual understanding on a concrete set of rules when such digitalization of cultural heritage occurs is lacking in current practices. To avoid such risks of generating undesired or lacking databases of information and to make the most efficient use of digital heritage, it is essential similar projects define protocols for how the data should be gathered and processed.

Figure 3: Challenges of Digital Application in Cultural Heritage. Source: IVOW, Venice Time Machine Project.

CONCLUSION

The transition to digitally sourced preservation efforts provides exciting new opportunities to better protect endangered cultural heritage and expand the scope of knowledge beyond what was imagined in the pre-digital era. Data-driven technology will enhance research capacities and possibly lead ways to constructing macro perspective on humanities. For a better prospect for cultural heritage in the digital era, preparatory measures should be taken to ensure the structural and technical support for digital-based initiatives. Institutions should seek out opportunities for collaborations with technology frontrunners such as IBM and Microsoft that fund and initiate their own projects on preserving cultural heritage using digital technology. It is also important to understand the current limitations of available technologies and needed improvements. Appropriate implementation of digital technology will help safeguard existing heritage and open a pathway to comprehensive digital humanities for posterity.

RESOURCES

“€1 Million in Funding for Time Machine!” International Institute of Social History. Accessed December 3, 2019. https://iisg.amsterdam/en/news/%E2%82%AC1-million-in-funding-for-time-machine.

“About Us.” CultLab3D. Accessed December 5, 2019. https://www.cultlab3d.de/.

Adhikari, Deepak. “Nepalese Question Rebuilding of Quake-Damaged Temples.” Nikkei Asian Review. April 29, 2018. Accessed November 20, 2019. https://asia.nikkei.com/Location/Southeast-Asia/Myanmar-Cambodia-Laos/Nepalese-question-rebuilding-of-quake-damaged-temples.

“AI for Cultural Heritage.” Microsoft. Accessed December 10, 2019. https://www.microsoft.com/en-us/ai/ai-for-cultural-heritage.

Ardalan, Davar. “Hey Google: Designing AI to Be Culturally Inclusive Will Take Time and Teamwork!” Medium. June 1, 2018. Accessed November 23, 2019. https://medium.com/@idavar/designing-ai-to-be-culturally-inclusive-will-take-time-and-patience-from-the-industry-3385269e922f.

Ardalan, Davar. “The Cultural Intelligence of AI.” IVOW. Podcast audio, October 28, 2019. Accessed December 1, 2019. https://www.ivow.ai/news--events/the-cultural-intelligence-of-ai.

Beer, Jeff. “How Intel Used Drones and AI to Help Fix Part of the Great Wall of China.” Fast Company. July 31, 2018. Accessed November 15, 2019. https://www.fastcompany.com/90210786/how-intel-used-drones-and-ai-to-help-fix-part-of-the-great-wall-of-china.

Castelvecchi, Davide. “Venice ‘Time Machine’ Project Suspended Amid Data Row.” Nature. October 25, 2019. Accessed December 9, 2019. https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-019-03240-w.

“Charter on the Preservation of Digital Heritage.” UNESCO. Accessed December 1, 2019. http://portal.unesco.org/en/ev.php-URL_ID=17721&URL_DO=DO_TOPIC&URL_SECTION=201.html.

“CultLab3D: 3D Digitalization on the Conveyor Belt. Fraunhofer. Accessed November 22, 2019. https://www.fraunhofer.de/en/research/current-research/preserving-cultural-heritage/3d-digitalization.html.

Daws, Ryan. “Lack of STEM Diversity is Causing AI to Have a ‘White Male’ Bias.” Artificial Intelligence News. April 18, 2019. Accessed December 2, 2019. https://artificialintelligence-news.com/2019/04/18/stem-diversity-ai-white-male-bias/.

Evens, Tom. “Challenges of Digital Preservation for Cultural Heritage Institutions.” Journal of Librarianship and Information Science 43, no.3 (2011):157-165.

Ferriero, David S., Carla Hayden and David J. Skorton. “Notre Dame Fire Powerful Warning that We Must Protect America's Precious Heritage.” USA Today. April 17, 2019. Accessed December 8, 2019. https://www.usatoday.com/story/opinion/2019/04/17/notre-dame-cathedral-fire-american-museums-must-prevent-tragedies-column/3499790002/.

Forbes, Alexander. “Breakthrough in Virtualization of Museum Collections.” Artnet. July 24, 2014. Accessed November 20, 2019. https://news.artnet.com/art-world/breakthrough-in-virtualization-of-museum-collections-66386.

“Home.” IVOW. Accessed December 2, 2019. https://www.ivow.ai/.

Ibaraki, Stephen. “Artificial Intelligence For Good: Preserving Our Cultural Heritage.” Forbes. March 28, 2019. Accessed November 15, 2019. https://www.forbes.com/sites/cognitiveworld/2019/03/28/artificial-intelligence-for-good-preserving-our-cultural-heritage/#bdc25bd4e960.

Intel. “Intel Technology Aids in Preserving the Great Wall of China.” Intel Newsroom. July 16, 2018. Accessed November 18, 2019. https://newsroom.intel.com/news/intel-technology-aids-preserving-great-wall-china/.

Intel. “Restoring the Great Wall Made Possible By Intel Drones and AI.” Intel. Accessed November 18, 2019. https://www.intel.com/content/www/us/en/technology-innovation/restoring-great-wall.html.

Kaihao, Wang. “Intel and Chinese Foundation to Use AI, Drone Technology to Help Preserve Great Wall.” China Daily. April 27, 2018. Accessed November 19, 2019. http://www.chinadaily.com.cn/a/201804/27/WS5ae28a3fa3105cdcf651ae03.html.

Maier, Andreas. “Will Machine Learning Enable Time Travel?” Marktechpost. January 30, 2019. November 16, 2019. https://www.marktechpost.com/2019/01/30/will-machine-learning-enable-time-travel/.

“Notre-Dame: Massive Fire Ravages Paris Cathedral.” BBC. April 16, 2019. Accessed November 15, 2019. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-47941794.

Opam, Kwame. “The Smithsonian is Now Sharing 3D Scans of Artifacts with the Public.” The Verge. November 13, 2013. Accessed November 15, 2019. https://www.theverge.com/2013/11/13/5100190/the-smithsonian-is-now-sharing-3d-scans-of-artifacts-with-the-public.

Phillips, Dom. “Brazil Museum Fire: ‘Incalculable’ Loss as 200-year-old Rio Institution Gutted.” The Guardian. September 3, 2018. Accessed November 15, 2019. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2018/sep/03/fire-engulfs-brazil-national-museum-rio.

Rea, Naomi. “An Artist Has Won a Three-Year Legal Battle to Force a German Museum to Publicly Release Its 3D Scan of a Bust of Nefertiti.” Artnet. November 17, 2019. Accessed December 1, 2019. https://news.artnet.com/art-world/3d-scans-museums-nefertiti-1706181.

Rees, Marc. “ Le Scan 3D du Penseur de Rodin est un document administratif communicable. ” [3D Scan of Rodin’s The Thinker is a Communicable Administrative Document]. Nextinpact. June 24, 2019. Accessed December 2, 2019. https://www.nextinpact.com/news/107996-le-scan-3d-penseur-rodin-est-document-administratif-communicable.htm.

Stanton, Todd. “Top 5 Risks of Using Outdated Technology.” Meridian. April 14, 2016. Accessed December 1, 2019. https://www.whymeridian.com/blog/top-5-risks-of-using-outdated-technology.

“State-of-the-Art 3D Scanner Brings the Possibility of Mass Digitization to Museums Around the World.” Architizer. Accessed November 21, 2019. https://architizer.com/blog/inspiration/industry/state-of-the-art-3d-scanner-brings-the-possibility-of-mass-digitization-to-museums-around-the-world/.

“The Preservation of Culture Through Technology.” IBM 100. Accessed December 10, 2019. https://www.ibm.com/ibm/history/ibm100/us/en/icons/preservation/.

“Unleashing Big Data of the Past.” Time Machine. Accessed November 17, 2019. https://www.timemachine.eu/unleashing-big-data-of-the-past-europe-builds-a-time-machine/.

“Venice Time Machine Project – Current State of Affairs.” Time Machine. Accessed November 17, 2019. https://www.timemachine.eu/venice-time-machine-project-current-state-of-affairs/.

Viola, Roberto. “Using New Technologies to Preserve the Past.” European Commission. April 8, 2019. Accessed November 18, 2019. https://ec.europa.eu/digital-single-market/en/blogposts/using-new-technologies-preserve-past.

WP Brandstudio. “Preserving the Past with Cutting-Edge Tech.” The Washington Post. September 12, 2018. Accessed December 1, 2019. https://www.washingtonpost.com/brand-studio/wp/2018/09/12/feature/preserving-the-past-with-cutting-edge-tech/.