In March of 2019 an international group of artists, technologists, fintech specialists, cultural industry professionals and collectors gathered in Manama, Bahrain for the UNFOLD Art and FinTech Summit. The three-day conference covered a vast array of current and emerging intersections between technology and the art world, including VR, AI, Blockchain, the development of arts and cultural districts, and more. While some of these industries and topics may seem disparate, they are rapidly coalescing into an ecosystem. The speakers highlighted how technology is changing the art world and provided a glimpse of what the future may bring. For arts managers curious about what lies on the edge of the art & tech world, and what may be available everywhere in the near future, the following provides a summary of highlights.

Blockchain

The AAM’s 2019 TrendsWatch featured blockchain as a trend to keep an eye on. Blockchain’s current and expansive potential impact on art, and the art market in particular, was readily apparent at the UNFOLD Conference.

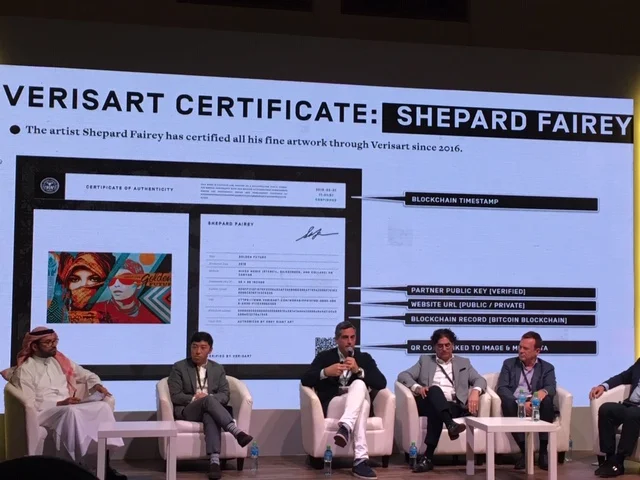

Robert Norton, CEO and Co Founder of Verisart, explains how the art registry works.

Art Registries

Blockchain based art registries are here and serve a variety of purposes. In the fall Artery, a blockchain based art registry system, partnered with Christie’s to offer the first sale of works supported with blockchain registered provenance. Other registries, such as Verisart, focus on allowing art owners and creators to register their works on a blockchain and generate certificates. These, and other registries, are designed to provide security to, and increase transparency in, a marketplace that traditionally relies heavily on trust and interpersonal relationships.

Digital “Fingerprinting” Art and Condition Records

For arts managers, blockchain-based condition reporting and digital “fingerprinting” tools may provide immediately useful options for augmenting collection records in their institutions. For example, 4ARTechnologies utilizes a smartphone camera to create a digital “fingerprint” of a work, which is supported by an augmented authentication technology and registered on a blockchain. Owners or institutions can update the condition record via smart phone as needed. When art is loaned or sold the recipient can verify at the click of a button that the correct piece has been received and have its complete condition history.

Caveats

Blockchain registries designed to provide assurances to art buyers and sellers come with one important caveat specific to artworks which are not added to the chain by their original artists. A blockchain should be viewed as providing an ownership record, and perhaps a recorded attribution to a specific artist, not necessarily an authentication of an actual art work. For many older works of art, authentication may require detailed scientific testing to prove facts such as artist, age and country of origin. Attribution typically comes from an expert asserting that in their opinion a work belongs to a specific artist. Attributions can, and do, change over time as our general body of knowledge increases. For example, a statue formerly attributed to Antonio Rossolino is now believed to be a work by Leonardo DaVinci. Therefore, while blockchains can provide a more secure record of ownership for a piece, this record of ownership should not be confused with scientific authentication.

Maurizio Serachini detailing the difference between authentication and attribution.

Mario Klingemann and Robbie Barrat discussing their work.

AI Generated Art

Today conversations around AI generated art often result in more questions than answers. For example, who is the artist – the machine or the person, and how does the input impact the output? Conference panelists Mario Klingemann and Robbie Barrat explained how their works uses generative adversarial networks which have been fed thousands of images to create pieces that are then selected by the artist. In attempting to define the art Robbie pointed out that it is the system itself that is the art piece. His latest work uses Balenciaga catalogs as a data set to create novel designs. While the skill set to create such works may be beyond many, new programs such as RunwayML are emerging to make generating AI art more user friendly and designed to further “augmented creativity.”

The Token Economy

People often speak of the gig economy, but the next wave may be the token economy. The token economy is in some ways as old as it is new. People have historically used tokens that holds value to trade for what they need or want. Today’s blockchain based tokens are being utilized in a diverse fashion. For example, the city of Vienna, in conjunction with a local university, is creating a token which, although still in the development process, may later be used to incentivize persons to do positive things such as ride a bicycle as opposed to driving, and then reward them with tokens that may be exchanged around the city for things such as theatre tickets. Similarly a token system could be utilized by a single or group of arts organizations to create cohesive cross institutional benefit systems for membership levels, unlock aspects of interactive art exhibits, or be utilized in gamification models.

Conference attendee exploring the Kremer Collection VR museum

VR Art and Museums

Virtual Reality as a concept has been around for a very long time, yet outside of gaming it has struggled to reach critical mass. However, a new wave of VR art and museums are highlighting the possibilities of VR presentations. Two VR museums, The DSL Collection, focusing on contemporary Chinese art, and The Kremer Collection, focusing on Dutch Realism, presented their VR collection to conference attendees. I had the chance to experience The Kremer Collection museum and the highly transportational nature of the VR technology did not disappoint. I was impressed by the highly detailed rendering of the images and the ability to get up close and personal with the artwork to the point where one could peek behind the frame.

Regarding VR, the collection leaders spoke of how for them the initiative wasn’t necessarily about technology, but how technology can serve art. For example, many museums can only display 2-4% of their collection at any given time, therefore adding a virtual reality museum to the offerings could increase the percentage of a collection available to the public without requiring building a large physical addition. For privately held collections, VR museums present a tool for sharing the works widely with the public. Finally, from an inclusivity perspective, VR experiences and museums increase accessibility by allowing those who are locationally bound, such as persons in long term hospital care, to experience the intrinsic benefits of art and museums when they would traditionally not be able to.

Final Thoughts

The UNFOLD conference highlighted the rapid ways in which technology is creating new intersections between artists, collectors, cultural institutions and the art market. While many of the technologies are not new to the technology space, their use in the arts world is at a tipping point for adoption by artists, collectors, and museums.