People move mountains where many individuals often perish in attempting their ascent. Systems have the capacity to coordinate people’s energy in a focused and complimentary way, and they can accomplish far more than what anyone alone can do. Crowdsourcing is one way that a system creates an artificial community with a few unexpected benefits. The following example will discuss the ways that the Smithsonian Institution's (SI) massive collection was levied by its organization to increase engagement, enhance knowledge diffusion, and offset chronic understaffing.

Five years ago, the SI invited the public to help transcribe diaries, labels, and ephemera from their archives. Since then nearly 10,000 volunteers have cataloged almost 350,000 pages of field notes, ledgers, logs, proofs, and albums. This case study, Smithsonian Institution Volunteers: Transcription Center, is insightful, defending the traditional field museum model, and demonstrating digital humanities as a catalyst for new growth in old institutions.

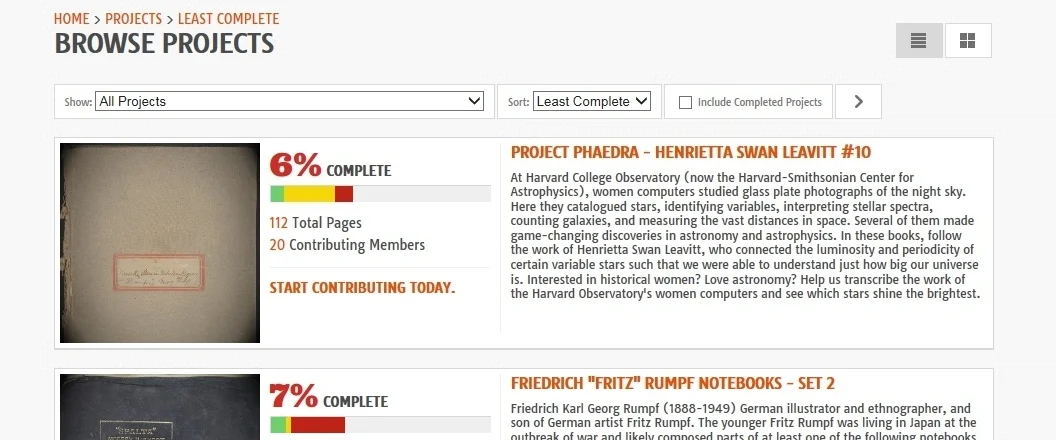

Source: screenshot by author

Volunteers worked through the dashboard as it appears in the picture above. Reading through the object from the archive, they would describe the text in the open fields on the right. Many of the notations are complicated and hard to describe in ordinary speech. Volunteers had to use their prior knowledge, experience, and creativity to find a way around this. If they experienced trouble, they would ask for help in the comments or skip the project altogether. With complex documents there is no ‘right’ transcription, only a ‘better’ one.

SI's collecting practice spreads across 19 museums of art, history, sciences, and scholarship. Each museum maintains an extensive library of documents related to the history of their collections so that it is accessible to independent scholars, curators, and educators. These collections need to be preserved and organized according to the principles of user experience design (UXD). Aside from UXD, centralized archiving and transcription are further complicated because each museum is autonomous in its operation and is designed according to its unique history and area of study. Accordingly, each museum has different collection archiving methods, containing articles such as catalogs, doodles on napkins, and small strips of paper. Many items are inconsistent, challenging to store, unstable, prone to deterioration, indecipherable, any yet potentially important for future scholarship. Digitization, as a process, systematically addresses most of these concerns. Far beyond merely scanning files and converting media, digitization requires the creation of new and specific data linkages between these objects and their environment.

Source: screenshot by author

Volunteers can choose how to serve the digitization process. Related items are aggregated into collections, or albums, where volunteers can narrow their project scope according to certain specifications. Many of these collection rulings are obvious, but there can be great variety between items within a collection, depending on the specific notation or entry. This provides greater opportunity for volunteers to specialize according to what skills they possess and what they hope to benefit from through the project.

PROCESS

Before digitization can proceed and be used in the model of crowdsourcing, there needs to be an investment in infrastructure where these intangible entities can exist and relate. To create this model, each archival object needs a digital equivalent, such as a picture, which will then be added to a relational database with a unique signature. Each of these digital objects can be populated with a selection of descriptive specifications, predetermined by the network administrator. This orients the user to the object, but also allows objects to be stored or shared, according to query-defined operating logic. Predefined attributes often include dimensions, materials, or physical locations of its tangible equivalent. Digital objects, however, can also be associated with image, audio, or text files, adding a more descriptive component than the attributes alone. Images may include photos, graphics, or file scans. Audio recordings may be live recorded or synthesized. Although text may be transcribed with character recognition software (CRS), CRS is unreliable with stylized handwriting often making manual entry more accurate. As an uninhibited string, text files can offer more nuance to a digital object record by incorporating the cataloger’s specific insights, creativity, and observations while maintaining a streamlined process for archiving.

Each object in the database needs to be searchable using any of the attributes, key-words, or specific object IDs. Any user within the computing network may have access to this relational database through their specific software authorization. Separate users can be granted different rights to view or edit. The crux of the archiving disparity rests with requiring users to run the software commands through a network recognized machine. An infrastructure in a closed network requires intermediary software, which creates a bottleneck.

Source: https://libraries.mit.edu/preserve/preservation-week-2014/

Making these archives web-based is a way around the closed-network disparity. This solution also makes the information publicly accessible in a safer, hosted format. It still maintains the organization’s oversight, but the software and access bottleneck are removed. Using volunteers to archive through open source, makes interactions nimble yet secure. Open access archiving uses the web-based host for the network. A UXD interface allows for transcription by volunteers to a linked relational database. The system uses hypertext, instead of queried logic, for exchanges of information between users and servers. Information is coded with a unique URL which can then be navigated using a web browser or another user interface. This Hypertext Transfer Protocol (HTTP) is coded to be generic, stateless, and object-oriented, making it very light in host development and quick in user processing power.

Under this format the digital object is located, rather than stored, within the internet according to a domain partly defined by its associated institution (most online museum collections follow this framework). Its architecture is then built according to this visage. Much of an existing infrastructure can be salvaged when prior data entries are migrated to a public facing network. There are over 137 million objects yet to be cataloged at SI and traditional methods cannot keep up.

With crowdsourcing, volunteers register to be assigned a unique user account throughout the portal. On this page are distinguishable media files, without description, organized into collections through tagged HML. Volunteers populate the text fields, into a temporary working file space, according to their perception while the portal tracks logs of their activity. Portal Administrators review the activity, deciding whether to approve or deny the changes and ranking contributors fairly. Most volunteers are motivated to participate through a sense of belonging to an organization, through learning something new, and through engagement within their community. Human intelligence tasks, as opposed to computer algorithms, provide an intimate connection between museum collections management and the public.

Source: screenshot by author

In addition to being varied and accommodating enough to serve a wide diversity of volunteers, the collections are vast and represent the entirety of the museum systems collections. Here you can see all the collections that are available for transcription through the Smithsonian Institution. If there is an area of interest that is particularly enticing to a volunteer, they may search to see if there is an active collection that they may start working out of. With categorical key word searches volunteers can keep momentum, jumping from project to project, making it easy to adapt to changing interests of this platform’s intended audience. In addition to being able to track the progress of completion in individual projects, this dashboard serves as an activity tracker for both themselves and the site administrators. This permits a new dimension of collection, allowing the Smithsonian to better understand some of its most passionate advocates.

It is not too presumptuous, in anticipation of a growing class of healthy retirees in and outside the US, to expect more people to find the merits in this activity and volunteer. As well, we can likely assume that the coding and design for these interfaces will become quicker and more user-friendly. Improving optics with mobile carrier options is empowering anyone to provide excellent images. With technological improvements, more volunteers would be encouraged to come forward with images, transcriptions, and catalogs for items outside the scope of an organization’s collection, permitting many of their missions to expand beyond their existing collections, staff, and neighborhood. Many historical societies and unrelated internet entities already permit this. With appropriate oversight, open source archiving can better preserve the nuance and richness of this world’s cultural heritage while embracing the technology of today.

Resources

“About.” Smithsonian Institution Archives. Accessed February 8th, 2018. https://siarchives.si.edu/about.

“About.” Smithsonian Digital Volunteers: Transcription Center. Accessed February 8th, 2018. https://transcription.si.edu/about.

Cameron, Fiona. "Digital Futures I: Museum Collections, Digital Technologies, and the Cultural Construction of Knowledge." Curator: The Museum Journal 46, no. 3 (2003): 325-340.

Crow, Kelly. “The Smithsonian Works to Digitize Millions of Documents.” The Wallstreet Journal. September 11th, 2014. Accessed February 8th, 2018. https://www.wsj.com/articles/the-smithsonian-works-to-digitize-millions-of-documents-1410464327.

Drucker, J. “Intro to Digital Humanities.” UCLA Center for Digital Humanities. September 2013. Accessed February 15th, 2018. http://dh101.humanities.ucla.edu/?page_id=13.

Kane, Elizabeth. “UX Design Explained Through a Maze of a Website.” Arts Management & Technology Laboratory. October 10th, 2017. Accessed February 15th, 2018. http://amt-lab.org/blog/2017/10/defining-ux-design-for-arts-orgs?rq=Design.

Kaplan, Isaac. “The Case against the Universal Museum.” Artsy. April 26, 2016. Accessed February 15th, 2018. https://www.artsy.net/article/artsy-editorial-the-case-against-the-universal-museum.

Levow, Gina-Anne, Helen Meng, Gabriel Parent, and David Suendermann. “Crowdsourcing for Speech Processing: Applications to Data Collection, Transcription and Assessment.” New York: Wiley, 2013.

Older, Susan. “Hennessy-Milner Logic.” Syracuse University, Engineering & Computer Science. September 26th, 2017. Accessed February 22nd, 2018. http://www.cis.syr.edu/~sueo/mcs/lectures/hml-handouts.pdf.

"OpenLink Releases Open Source ODBC and JDBC Driver Benchmark Utilities; OpenLink Simplifies Data Access Driver and Database Engine Benchmarking." PR Newswire, 2003.

Pontin, Jason. “Artificial Intelligence, With Help from the Humans.” The New York Times, March 25th, 2017. Accessed February 15th, 2018. http://www.nytimes.com/2007/03/25/business/yourmoney/25Stream.html.

Pundsack, Karen. “Is Your Library User-Centered?” Public Libraries Online. February 29th, 2016. Accessed February 15th, 2018. http://publiclibrariesonline.org/2016/02/is-your-library-user-centered/.

Serven, Ruth. “Collaborative effort drives UVa Law Library transcription project”. The Daily Progress. November 24th, 2017. Accessed February 8th, 2018. http://www.dailyprogress.com/news/local/collaborative-effort-drives-uva-law-library-transcription-project/article_a9493650-d167-11e7-ba7a-d394f37e41c6.html.

Schuessler, Jennifer. "Smithsonian Asks Public for Transcription Help." The New York Times, Artsbeat. August 8th, 2014. Accessed February 8th, 2018. https://artsbeat.blogs.nytimes.com/2014/08/12/smithsonian-turning-to-the-public-to-help-transcribe-documents/.

Smith, Kari R. "PAIMAS and OAIS diagram showing Producer and Archive responsibilities." MIT Libraries. August 20th, 2013. Accessed February 15th, 2018. https://libraries.mit.edu/preserve/files/2015/02/PAIMAS_storage_tools_flow.jpg.

“Smithsonian.” Smithsonian Institution. Accessed February 8th, 2018. https://www.si.edu/.