By: Noah Jang

I saw the backyard cedar where the mourning doves roost charged and transfigured, each cell buzzing with flame. I stood on the grass with the lights in it, grass that was wholly fire, utterly focused and utterly dreamed. It was less like seeing than like being for the first time seen, knocked breathless by a powerful glance… I had been my whole life a bell, and never knew it until at that moment I was lifted and struck.

Annie Dillard, Pilgrim at Tinker Creek

Pilgrim at Tinker Creek details author Annie Dillard’s exploration of nature around her home near Virginia’s Blue Ridge Mountains. Her piercing contemplations on nature and life were lauded by critics, and in 1975, Pilgrim won the Pulitzer Prize for General Non-fiction. Many of Dillard’s deepest reflections throughout the book are preceded by the act of “seeing”; the narrator often begins by observing her surroundings with an unparalleled intensity until she seemingly gets pulled above her usual sphere of consciousness — and is then hit with a profound realization.

While some are quick to dismiss Dillard’s accounts for their mystical undertone, the experience of “losing oneself” while observing a visual phenomenon closely, though rare, is not unfamiliar to many. We have all been either absorbed in the brushstrokes of a masterpiece in a museum; overwhelmed by the vastness of universe while stargazing; hypnotized by the dancing flames at a bonfire; or thrown into a dreamlike state while cloud-watching. This is why, insofar as the VR technology seeks to recreate (especially visual elements of) life, its developers and prospective adopters must keep asking one very important question: how deeply can VR impact us?

Attention Restoration Theory

Recently, multiple groups of psychologists have begun to approach this question from an angle that Dillard may also appreciate. They are researching if exposure to nature in VR, like in real life, can positively influence one’s mental well-being. In particular, many groups have tested the validity of Attention Restoration Theory (ART) under VR settings. First introduced in 1989 by Rachel and Stephen Kaplan in their book The Experience of Nature, ART suggests that nature is capable of restoring attention after mental energy has been exerted (Kaplan, 1989).

The theory was constantly tested and developed in the following decades, with notable discoveries made in specific areas of attention restoration, including recoveries from mental fatigue and stress. A 1991 study by Hartig, Mang, and Evans provided the initial support for ART (Hartig, et. al, 1991). In this study, the researchers separated subjects into two groups — one that would vacation in an urban area, and another that would vacation in the wilderness. They gave both groups tasks that would result in mental fatigue, and measured the performance of both groups before and after the vacation. They found that, while those who vacationed in an urban area performed worse than they did before the vacation, those who spent time in the wilderness performed better.

Then, a 1995 study by Tennessen and Cimprich on 72 undergraduate students showed that those with more natural views from their dormitory windows — ranging from all built view to all natural view — had “a stronger capacity to direct attention than those with less natural or built views,” suggesting that “an attention-restoring experience can be as simple as looking at nature” (Tennesen and Cimprich, 1995).

Finally, Rita Berto demonstrated in 2005 that the recovery from mental fatigue could be made merely from staring at photographs of restorative environments (Berto, 2005). In this experiment, which is frequently quoted as an inspiration for the recent ART studies involving VR, the participants that were mentally fatigued from an initial sustained attention test viewed photographs of restorative environments, nonrestorative environments, or geometrical patterns. When they performed the sustained attention test again afterward, “only participants exposed to the restorative environments improved their performance.”

As mentioned, notable discoveries were made in the area of stress recovery as well, though, for concision, only one study will be mentioned in this paper. In a 2010 study, van den Berg, Maas, Verheij, and Groenewegen reported that “the relationships of stressful life events with number of health complaints and perceived general health were significantly moderated by [the] amount of green space in a 3-km radius” (van den Berg et. al., 2010).

Nature in VR

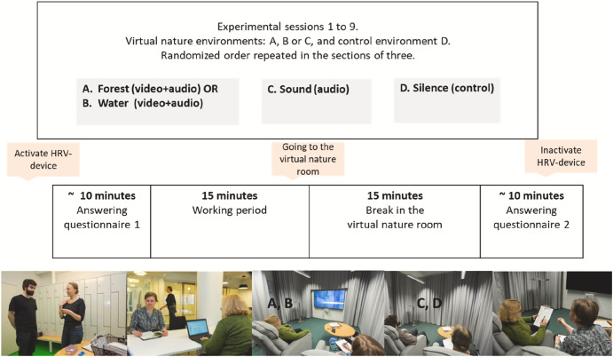

While the restorative capacity of nature is now well established in the field of environmental psychology, in recent years, multiple groups of researchers have begun to test if ART would remain applicable under VR settings. One such research took place in 2022 to test the restorative benefits of VR nature rooms in the office environment (Ojala et al, 2022). During their 15-minute breaks, the volunteers either watched a video of a restorative environment, listened to nature sounds, or sat in the quiet room without audio-visual material. They measured the participants’ heart rate variability (HRV) and collected phycological measures throughout the experiment.

Figure 1. The experimental plan used by Ojala et al.

The result indicated that watching the video “increased the felt restoration more than the audio and the control conditions.” What confounds the result — as can be seen from Figure 1 — is that the VR nature room used for the experiment was not a VR setting in a conventional sense.

A similar study further developed on this work by creating more immersive nature rooms, as can be seen in Figure 2. (Kumpulainen et. al., 2024). Many physiological markers including HRV, heart rate, and respiratory rate were measured, and various psychological measures were collected through questionnaires. The study revealed that the exposure to VR nature resulted in not only “higher HRV and reduced heart rate, indicative of enhanced parasympathetic activity,” but also “decreased feelings of anxiety and depression, with an increase in comfort, enthusiasm, creativity, and belonging.”

Figure 2. Nature rooms used in the experiment. . (McAnirlin et. al., 2024)

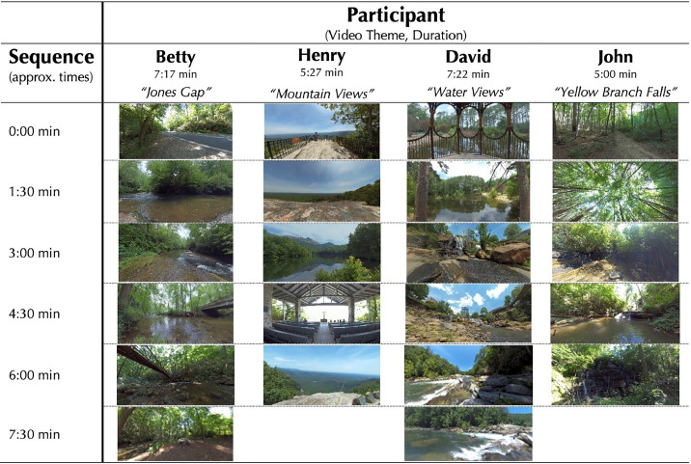

Most recently, a 2024 proof-of-concept study by McAnirlin et al. implemented full 360-VR experiences (2011). For this experiment, the researchers co-created personalized nature-based VR experiences with four patients of severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). They identified and captured 360-degree videos of locations that were both familiar and meaningful to the participants, and worked together to “select the videos, audios, and sequences to use.” The participants experienced their unique videos (figure 3), during which their physiological data on heart rate, HRV, respiratory rate, and blood oxygen levels were collected. They were also measured with “questionnaires on psychological wellbeing, perceived restoration, cybersickness, and presence.” The study reported that the experience was not only safe for the participants but also enhanced the participants’ psychological well-being on multiple fronts.

Figure 3. Videos created by four patients with COPD. (McAnirlin et. al., 2024)

Museums in VR

The only way to understand painting is to go and look at it. And if out of a million visitors there is even one to whom art means something, that is enough to justify museums.

A fitting quote attributed to one of the leaders of the Impressionist movement, Pierre-Auguste Renoir (Renoir, 1962). Many elements of his words ring true to this day. Indeed, there is an undeniable stir that one experiences when confronted with a work of art on the wall of a museum instead of inside a textbook. What has changed in recent decades, however, is that there may now be more ways to “go and look at it.”

Leading up to COVID-19, museums around the world openly embraced and experimented with VR to aid and enhance their shows. Some shows like Tate’s Modigliani VR: The Ochre Atelier conducted rigorous research to faithfully recreate the artist’s studio, while The Louvre included a VR experience of Mona Lisa in its Leonardo da Vinci exhibition, where the mythical subject was reimagined to interact with the visitors ("Modigliani in VR"). Meanwhile, the Kremer Collection took a larger stride by creating a fully virtual museum (“The Kremer Collection“) It is to be noted that the latter two experiences are still available through on Steam — they are respectively sold for free and $9.99 (“Mona Lisa: Beyond the Glass on Steam”).

Closing Thoughts

The years I lived in a banjiha apartment, now popularized through its appearance in Bong Joon-ho’s Parasite, were by far the darkest days of my life. I mean this at once metaphorically and literally. Fresh out of my mandatory military service and for first time fully independent with a younger brother to support, there was not much of a choice for me but to live in the semi-basement apartment with two semi-windows — each allowing precisely 7.2 in. x 23 in. of external light — if I wanted to live and work in Seoul.

This is how I personally knew, before reading all of the research, that nature mattered. But if there was another thing that I felt that made my life exceedingly difficult during my time in a banjiha, it was knowing that I not only lacked rays of sunlight, but also the time and resources to go catch exhibitions.

Post-COVID museums have visibly lost their interest in incorporating VR into their shows. Some quote the general loss of interest in the metaverse as the cause, while others talk of logistical issues such as cost and hygiene — which are all understandable. But I am more driven than ever to seek ways to bring it back. Because, after all this research and experience, I catch myself wondering, “Would my life have been any warmer a few years ago if I knew that VR could bring the Sun and the Arts back into my life?” The answer is yes.

-

Berg, Agnes E. van den, Jolanda Maas, Robert A. Verheij, and Peter P. Groenewegen. “Green Space as a Buffer between Stressful Life Events and Health.” Social Science & Medicine 70, no. 8 (April 1, 2010): 1203–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.01.002.

Berto, Rita. “Exposure to Restorative Environments Helps Restore Attentional Capacity.” Journal of Environmental Psychology 25, no. 3 (September 1, 2005): 249–59. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2005.07.001.

Dillard, Annie. Pilgrim at Tinker Creek. New York, NY: Harper Perennial Modern Classics, 2007.

Frick VR Screen Recording. Frick Park, 2024. https://vimeo.com/manage/videos/1018162910.

Hartig, Terry, Marlis Mang, and Gary W. Evans. “Restorative Effects of Natural Environment Experiences.” Environment and Behavior 23, no. 1 (1991): 3–26.

Kaplan, Rachel. The Experience of Nature: A Psychological Perspective. Cambridge ; Cambridge University Press, 1989.

Kumpulainen, Susanne, Samad Esmaeilzadeh, and Arto J. Pesola. “Assessing the Well-Being Benefits of VR Nature Experiences on Group: Heart Rate Variability Insights from a Cross-over Study.” Journal of Environmental Psychology 97 (August 1, 2024): 102366. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2024.102366.

Le Louvre. “The Mona Lisa in Virtual Reality in Your Own Home,” 1615970843. https://www.louvre.fr/en/explore/life-at-the-museum/the-mona-lisa-in-virtual-reality-in-your-own-home.

McAnirlin, O., M. H. E. M. Browning, T. Fasolino, K. Okamoto, I. Sharaievska, J. Thrift, and J. K. Pope. “Co-Creating and Delivering Personalized, Nature-Based VR Experiences: Proof-of-Concept Study with Four U.S. Adults Living with Severe COPD.” Wellbeing, Space and Society 7 (December 1, 2024): 100212. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wss.2024.100212.

“Mona Lisa: Beyond The Glass on Steam,” n.d. https://store.steampowered.com/app/1172310/Mona_Lisa_Beyond_The_Glass/.

“Museum – The Kremer Collection,” n.d. https://thekremercollection.com/museum/.

Ojala, Ann, Marjo Neuvonen, Mika Kurkilahti, Marianne Leinikka, Minna Huotilainen, and Liisa Tyrväinen. “Short Virtual Nature Breaks in the Office Environment Can Restore Stress: An Experimental Study.” Journal of Environmental Psychology 84 (December 1, 2022): 101909. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2022.101909.

Renoir, Jean. Renoir, My Father (New York City: New York Review of Books, 1962), 58.

Tate. “Modigliani VR.” Tate, n.d. https://www.tate.org.uk/whats-on/tate-modern/modigliani/modigliani-vr-ochre-atelier.

Tennessen, Carolyn M., and Bernadine Cimprich. “Views to Nature: Effects on Attention.” Journal of Environmental Psychology 15, no. 1 (March 1, 1995): 77–85. https://doi.org/10.1016/0272-4944(95)90016-0.

“The Kremer Collection VR Museum on Steam,” n.d. https://store.steampowered.com/app/774231/The_Kremer_Collection_VR_Museum/.