This post was excerpted from the research conducted and report written by Carnegie Mellon Master of Arts Management students Daria Butler, B Crittenden, Daral Moore-Washington, Jackson Smith, and Freya Zhang.

Introduction

Nonprofit arts and cultural organizations are designed to serve a community. In the 21st century funding model, they also must find ways to collect the evidence for the impact their work has on their constituents, analyze the data, and effectively tell their stories. The following research provides an understanding of what types of impact can be measured with suggestions on how to measure and visualize findings on a budget.

There is no standardized set of impact indicators appropriate for any given organization, especially visual artist studios; rather, an organization should institute a set of indicators specific to their mission, goals, and its target audiences’ needs. Furthermore, the actual data collection requires intentional design. Important elements of the data collection process are:

Define the purpose

Establish a collection plan

Build trust through communication

Use a mix of collection methods

Make the process continuous

Most importantly, alongside trust, humanity and privacy should not be discounted since data comes from people. For this process, it is essential to include both qualitative and quantitative data in assessing and communicating impact.

Impact

To better understand the concept of “‘impact,”’ one can look to the research and consulting firm Wolf Brown and its work with the Canada Council for the Arts’ (CCA) Qualitative Impact Framework. The study notes that impact is often simply defined as “the effects of a program on individual participants.” However, the study notably broadens impact to a larger sense, meaning the impact as it is experienced by both the artists and organizations who receive the benefit of CCA’s funding, e.g. the ways that funding “shapes the careers of artists or catalyzes an organization.”

Impact indicators are standards of measurement to track the progress of change. Making claims about impact relies on the change of measures over time, not on the isolated results. This is what distinguishes impact from the outputs and outcomes of a project or program.

Economic Impact

Economic impact is one element of impact that has been expansively used and defined by Americans for the Arts. Economic impact is the effect of the initial and subsequent expenditures by businesses and individuals within a community. Furthermore, there are distinctions as between direct, indirect, and induced economic impact, indicated below.

Direct economic impact: a measure of the economic effect of the initial expenditure within a community

Indirect and induced economic impact: the effects of the immediately subsequent round of spending by businesses and individuals, respectively

Common economic impact indicators of arts and culture organizations are:

Figure 1: Diagram of direct and indirect economic impact. Source: Authors.

Social Impact

Social impact is considered “those effects that go beyond the enactment of a service itself and have a continuing influence upon people’s lives,” a definition adapted from Landry et al.’s 1995 paper “The Social Impact of the Arts.” A more recent definition of social impact that guided this research is: “results measured in the form of changes within the target group.”

It is important to note that social impact focuses on the results of an output, not the output or the services, products, and activities offered alone. Social Impact Navigator distinguishes between these categories of indicators and organizes them into three buckets:

Figure 2: Diagram of social impact indicators based on information from Social Impact Navigator. Source: Authors.

Like their economic siblings, social impact indicators can also be categorized by direct and indirect aspects of impact:

Direct social impact: indicators formulated primarily for countable facts or states of affair, such as outputs or easily measured results, often emerging directly from the project objectives

Indirect social impact: indicators that point only indirectly to the observable state of affairs; they’re used when it’s impossible—or only possible after unjustifiably high expenditure—to collect data.

Common social impact indicators of arts and culture organizations are:

Figure 3: Diagram of direct and indirect social impact indicators based on information from Social Impact Navigator. Source: Authors.

Literature on impact highlights that indicators identified for any given organization attempting to measure its impact depend on the target group and its particular needs. Ultimately, a variety of different impacts emerge when based on different stakeholder groups, such as the ones detailed below in relation to the impact of artists’ centers.

Artists

Working spaces devoted to artists (referred to as “artists’ centers” in Ann Markuson and Amanda Johnson’s 2006 report, “Artists' Centers: Evolution and Impact on Careers, Neighborhoods and Economies”) have impacted artists’ careers by furthering the quality of artists’ work and enabling more of them to make a living at it. They cite artists’ centers as fostering connections between artists, allowing for emerging artists to find encouragement and deepen their knowledge.

Community

According to the Center for Cultural Innovation, “Artists often have critical roles as community leaders, giving shape to community identity and voice to community concerns and aspirations.” As many studies on social impact of the arts suggest, “when people participate in the arts, society benefits. People in a society can become more connected, they can experience general feelings of wellbeing and a sense of belonging in their communities, and they can even become more creative at work.” Artists who use these centers often work in various capacities: as educators, administrators, and community leaders, just to name a few, thereby contributing to the civic and social vitality of areas.

Neighborhoods

Artists’ centers tend to contribute to the vitality and safety of their neighborhoods by bringing in foot traffic and occupying previously vacant buildings.

Regional Economy

By accommodating artists, artists’ centers counter the risk of losing artists to other regions, thereby helping to sustain regional creative economies. Some artists begin businesses that create jobs for others in the community. For example, Pittsburgh Quarterly measures the following indicators of economic impact of the arts, in general, in Pittsburgh:

Employment by Arts Establishments

Number of Arts Establishments

Number of Arts Establishments

Employment by Arts Establishments

Household Income Economic Impacts

Audience Spending Expenditures

Total Spending Expenditures

Grants to the Arts per Capita

Private Giving to the Arts per Capita

Arts Revenue per Capita

Jobs Economic Impact

Tax Revenues Economic Impacts

Organizational Spending Expenditures

Determining what to measure is the first step, but measuring impact requires the use of formal data collection methods. The literature addressing best practices is summarized below.

Why Organizations Need Good Data Collection

In the articles “Proper Data Collection for Nonprofits: Why Does it Matter?” and “Why Nonprofits Need to Care About Proper Data Collection,” Katie Biondo and Christina Wells both mention that one of the most critical aspects of data is that it can be a gold mine of useful information or it can be inadequate for any purpose. Leveraging good data can be immensely useful in helping a nonprofit stay up and running with limited resources, or better yet, make impactful changes for the future. Far too often, however, nonprofit organizations do not have access to the right data or proper visibility into data they already have, or the quality of their data is questionable. Biondo pointed out that, according to a study by Nonprofit Hub, 90% of nonprofits reported they are collecting data, but a surprising 49% stated they didn’t know how data was being collected. Kathleen Janus also stated something similar: that 75% of nonprofits collect data, but only 6% think they use it well. Several issues arise when there is no visibility into how or where data is being collected: “Data analysis can be negatively impacted, but what is worse is that the overall quality of the information may be compromised,” said Wells. Organizations need to realize that bad or inaccurate data can only create an incomplete picture, thus robbing an organization of the opportunity to do anything with the information.

In general, data collection can:

Serve as a systematic way to measure and prove impact

Make informed, data-driven decisions to better serve the audience

Present evidence for results to funders when asking for contributions

Once organizations have built healthy data systems that collect and aggregate data, it is critical to know if their efforts are working. Measuring impact helps organizations tell and prove their story of impact to funders and other stakeholders. It also provides internal information necessary to make improvements to operations and processes.

Importance of Data Collection

Data collection should be carried out in a systematic and organized way. The literature presents it as a linear but continual process:

Figure 4: Visualization of the data collection process from INTRAC. Source: Authors.

It is always crucial to know why information is needed. If the answers to any of the “what, where, why, who, and how” questions are unknown or uncertain, then it is important to find out the answers before going any further.

Additionally, there should be a detailed collection plan established before collecting the data. The plan should lay out procedures for collecting data relating to each metric, including how and when data will be collected and from which sources. The plan should also prescribe how data will be validated before they are entered into the system. Organizations also need to be aware of the ramifications of incorrect or incomplete data and the problems that can result from biased samples.

It is necessary and helpful to have a standard formatting across different data sets from a certain data collection method. Consistent data formatting makes the process easier for future data collection and also empowers organizations to track their performance.

There are three key principles that organizations should be aware of in data collection:

Trust. It’s critical that participants trust organizations using their personal information and have a clear idea of what the data is for and how the data will be used. All the data must be given local context in the form of “ground-truth”—information coming directly from the artists surveyed.

Humanity. It’s a basic human need to want to connect with others. Thus, finding ways to humanize data and figure out how the organization should talk about data is critical.

Privacy. It’s important that participants are in charge of their own data. They should be able to have a say in, if not outright control of, what happens with data collected from them.

More importantly, art’s impact is never done, even when the data is all counted. Art’s impact echoes insofar as it keeps unfolding at yet-to-be discovered levels of experience and insight. Reducing it to a set of quantifiable data creates a false sense of closure. Thus, data collection should be a continuous process with up-to-date information as well as historical data available.

Quantitative Data Collection

Identifying the differences in collection needs between quantitative and qualitative data is also important. Quantitative data collection measures attitudes, behaviors, opinions and other variables to support or reject a premise. This data type is usually numerical, which is easily quantifiable to identify “statistical significance.” Common methods include:

Surveys

Experiments

Controlled observations

Longitudinal studies

Polls

Telephone/Face-to-face interviews (with close-ended questions)

Figure 5: Comparison of the advantages and disadvantages of quantitative data collection. Source: Authors.

The common methods that most organizations can easily implement are surveys and telephone/face-to-face interviews (with close-ended questions). Though organizations send out surveys for data collection, many times the response rates are not ideal.

When creating and conducting surveys, the survey designer must consider the following rules to help create more effective results: 1.) each question in the survey should ask only one question at a time with clear, common language and 2.) the questions should use shorter words to help keep each question under twenty words. These elements help to get clearer responses, which can better inform the results after analysis. They also help ensure that the respondents understand what is being asked so they can give a more accurate and realistic answer to each of the questions. A survey consists of both open-ended and closed-ended questions. Open-ended questions ask the taker to use their own words to answer the questions, while closed-ended questions have the taker select from a list of options. The list should be limited to a small number of responses, usually four or five, to help analysis and conclusion creation. Both types of questions can get qualitative and quantitative responses.

Survey designers also must consider several different effects that can influence results:

Figure 6: Table of effects that can influence survey results from Pew Research Center. Source: Authors.

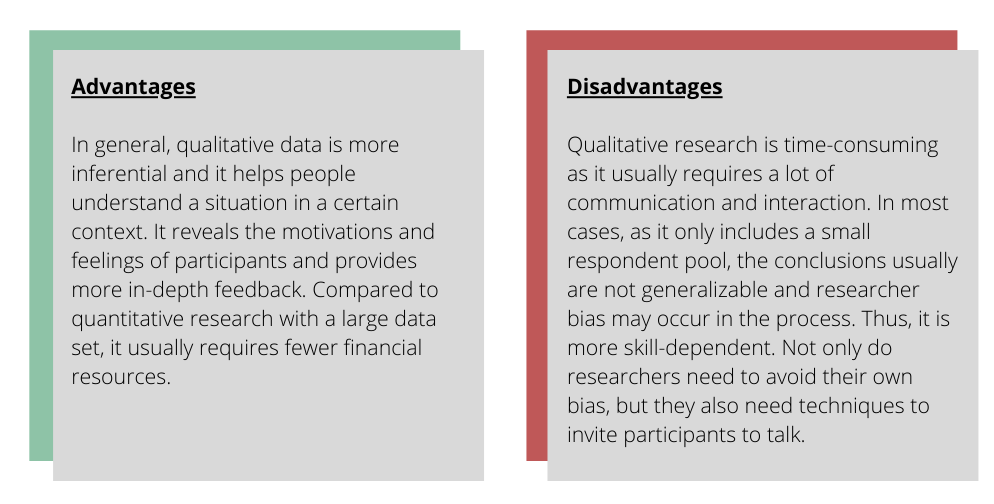

Qualitative Data Collection

Qualitative data is defined as data that approximates and characterizes. This data type is usually non-numerical. Compared to quantitative data collection, qualitative data collection typically produces detailed data about a much smaller number of people. However, it provides rich information through direct quotations and careful description of programs, events, people, interactions, and observed behaviors to answer “why” and “how.” Common methods include:

Interviews

Case studies

Secondary research (record keeping)

Expert opinions

Focus groups

Observational studies

Figure 7: Comparison of the advantages and disadvantages of qualitative data collection. Source: Authors.

Among all the qualitative data collection methods, interviews are most commonly used and can be easily carried out. In comparison to written surveys, qualitative interviews have the advantage of being interactive and allowing for unexpected topics to emerge and be taken up by the researcher. More importantly, the only way to catch a glimpse of an ongoing process at work is to listen to those whom an organization impacts speak their own words, in their own voices, through speaking methodologies friendly to dialogue. By carrying out interviews periodically, not only can an organization obtain up-to-date information about its stakeholders, but it can also build the artist community along the way.

In summary, qualitative research is good at answering questions regarding “why” and “how” while quantitative research is good at describing “who,” “what,” and “when.” Thus, it’s necessary to combine qualitative and quantitative research methods to have a deep understanding of the participants.

Conclusion

Establishing consistent data tracking is important for arts organizations wanting to measure and communicate their community impact. Finding the best system involves weighing what to measure (social or economic impact) and what kind of data to collect (quantitative vs. qualitative). The next post in this series will look at how to analyze and visualize that data, even with limited resources.

Resources

Alvarez, Maribel. “Two-Way Mirror: Ethnography as a Way to Assess Civic Impact of Arts-Based Engagement in Tucson, Arizona.” 2009. http://animatingdemocracy.org/sites/default/files/Two-Way%20Mirror.pdf.

Americans for the Arts. “Arts & Economic Prosperity 5: The Economic Impact of Nonprofit Arts & Cultural Organizations & Their Audiences.” https://www.americansforthearts.org/sites/default/files/aep5/PDF_Files/ARTS_AEPsummary_loRes.pdf.

Biondo, Katie. “Proper Data Collection for Nonprofits: Why Does it Matter?” Omatic, March 14, 2018. https://omaticsoftware.com/blog/proper-data-collection-nonprofits.

Brown, Alan. “An Architecture of Value.” Grantmakers in the Arts, accessed October 28, 2020. https://www.giarts.org/article/architecture-value.

Brown, Alan, John Carnwath, and James Doeser. “Qualitative Impact Framework.” Canada Council for the Arts, November 2019. https://www.wolfbrown.com/post/qualitative-impact-framework.

Brown, Mitchell, and Hale, Kathleen. Applied Research Methods in Public and Nonprofit Organizations. New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons, Incorporated, 2014. ProQuest Ebook Central. https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/cm/detail.action?docID=1767442.

Center for Cultural Innovation. “Creativity Connects: Trends and Conditions Affecting U.S. Artists.” National Endowment for the Arts, 2016. https://www.arts.gov/sites/default/files/Creativity-Connects-Final-Report.pdf.

Epstein, Marc and Kristi Yuthas. Measuring and Improving Social Impacts: A Guide for Nonprofits, Companies, and Impact Investors. San Francisco: Berrett-Koehler Publishers, 2014. https://ssir.org/books/excerpts/entry/measuring_and_improving_social_impacts.

Hinze, Florian. “Types of Indicators.” Social Impact Navigator, accessed November 28, 2020. http://www.social-impact-navigator.org/impact-analysis/indicators/types-of-indicators/.

Jones, Johanna. “Quantifying Our Museum’s Social Impact,” Medium, May 14, 2020, https://medium.com/new-faces-new-spaces/quantifying-our-museums-social-impact-e99bff3ef30e.

Landry, Charles, Franco Bianchini, and Maurice Maguire. “The Social Impact of the Arts: A Discussion Document.” Bournes Green, Gloucestershire: Comedia, 1995.

Markusen, Ann and Amanda Johnson. “Artists’ Centers: Evolution and Impact on Careers, Neighborhoods and Economies.” Americans for the Arts, January 31, 2006. https://www.americansforthearts.org/by-program/reports-and-data/legislation-policy/naappd/artists-centers-evolution-and-impact-on-careers-neighborhoods-and-economies.

Pew Research Center. “U.S. Survey Research.” https://www.pewresearch.org/methods/u-s-survey-research/.

Pittsburgh Today. “Indicators.” Pittsburgh Quarterly, accessed September 15, 2020. https://pittsburghquarterly.com/indicators/arts/.

Rasmussen, Wiebe. “Defining Social Impact.” Social Impact Navigator, accessed November 28, 2020. http://www.social-impact-navigator.org/planning-impact/defining-social-impact/.

Simister, Nigel and Anne Garbutt. “Principles of Data Collection.” INTRAC, 2017. https://www.intrac.org/wpcms/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/Principles-of-data-collection.pdf.

“Social Impact of the Arts,” Americans for the Arts, May 15, 2019, https://www.americansforthearts.org/socialimpact.

Sopact. “Social Impact Metrics | Best Practices 2020.” Accessed December 17, 2020. https://www.sopact.com/social-impact-metrics.

Surendran, Anup. “Quantitative Data: Definition, Types, Analysis and Examples.” LaptrinhX, May 25, 2018. https://laptrinhx.com/quantitative-data-definition-types-analysis-and-examples-1602195233/.

Wells, Christina. “Why Nonprofits Need to Care About Proper Data Collection.” GuideStar Blog, April 2, 2018. https://trust.guidestar.org/why-nonprofits-need-to-care-about-proper-data-collection#:~:text=When%20it%20is%20collected%20and,the%20reliability%20of%20your%20data.