Many museums are beginning to experiment with beacons as way to serve visually-impaired visitors.

With the growing emphasis on providing learning experiences that occur outside the classroom, accessibility and inclusivity is of paramount importance to museums as they transition into the 21st century. Museums today have a strong focus on community and outreach, and strive to provide engaging experiences that create informal learning opportunities for both students and adults. In terms of accessibility and ADA compliance, museums have made significant strides over the past two decades in welcoming and including people with disabilities, from building ramps and elevators to providing large text labels and American Sign Language guided tours. While these advancements are noteworthy, oftentimes they fall short in their overall effectiveness in that they only address physical needs. Rather, it is important to remember that many people who are differently abled communicate in ways that are different from people without disabilities, and that certain museum experiences still remain inaccessible for such visitors. As museums become more inclusive, it is imperative that their methods of communication are equally effective between people with disabilities and those without.

This topic is especially relevant today as digital technology is rapidly becoming a major part of everyday life, shaping the way we interact with each other, with institutions, and with everyday services such as going to the bank or gym. One area of concern for the blind community, for example, is the widespread use of touchscreens. With some exceptions, touchscreens typically do not cater to the needs of blind people, thus limiting their ability to “see with their fingers” and leaving them feeling “truly blind.” This particular example alludes to a phenomenon known as the digital divide, in which certain demographics or regions have unequal or restricted access to information and communications technology.

What’s New in Accessibility Technology?

The Beam, a telepresence robot, allows homebound art lovers to explore famous museums from the comfort of their homes.

In an effort to combat some of the effects people with disabilities experience as a result of the digital divide, museums are implementing improved technological services to enhance the museum experience. The past few years have seen some exciting developments in technology’s ability to allow people with visual, hearing, and physical disabilities experience art in deep and meaningful ways that may not have been possible a decade ago.

The Beam, for example, is a telepresence robot that allows quadriplegic art lovers to take one-on-one guided tours through a museum. The robot is remotely controlled, uses a voice synthesizer, and responds to head motions; as such, it can be navigated by simple movements of the head. Henry Evans, a mute quadriplegic who became disabled after suffering a stroke in 2002, is one of the first users to consistently operate the Beam. Evans is a strong advocate for increased accessibility in museums, and uses the robot to explore museums around the world. He creates partnerships along the way in hopes of expanding the Beam’s widespread use across the globe.

Virtual models such as the interactive Augsburg Display Cabinet at the Getty museum are also great examples of accessibility-friendly technology for homebound and Deaf museumgoers, as are virtual logs (vlogs for short). The Vlog Project at the Whitney Museum is an excellent example of a museum experience that is catered specifically to the Deaf community. The Project features original short videos presented in American Sign Language that discuss topics in contemporary art on view at the museum.

Other advancements for visitors with hearing impairments include a whole host of Assisted Listening Devices (ADLs), or devices that amplify the volume of a desired sound without increasing the background noise. There are many kinds of ADLs in use, one of the most popular of which is an induction loop. Induction loops electromagnetically transmit sound to an individual’s telecoil (t-coil) in their hearing aid or cochlear implant. The loops can then be used to make videos and audio experiences available to visitors who are deaf or hard of hearing, as the Indiana State Museum does to enhance its accessibility offerings for the Deaf community.

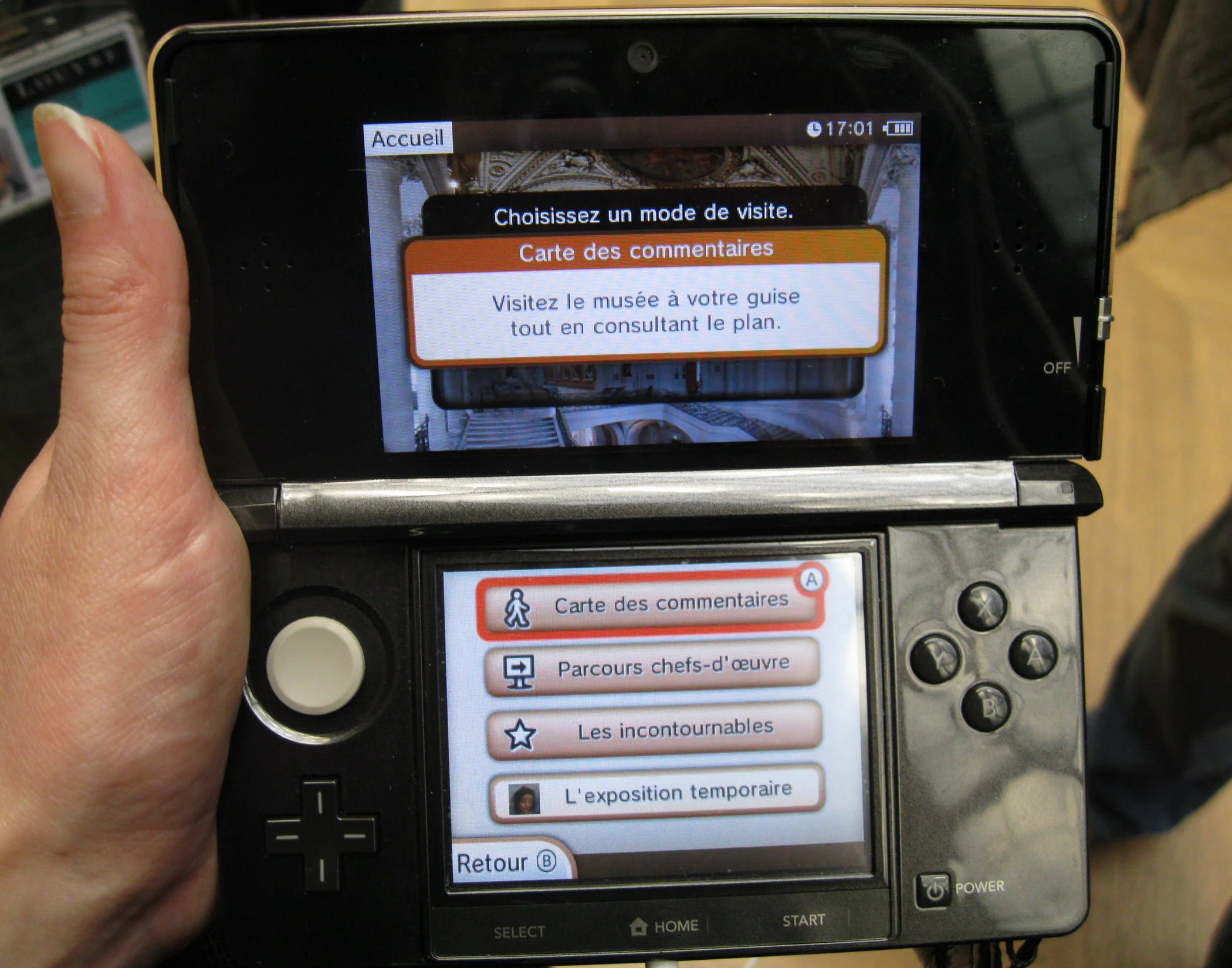

The Louvre's Nintendo 3DS offers in-depth audio guides as well as location mapping services, which is a useful feature for visually-impaired visitors.

For those with visual impairments, many museums are incorporating tactile exhibits into their repertoire, as well as updated audio guides and apps that integrate large text formats and beacon-like technology. The Louvre released its Nintendo 3DS audio guides in 2013 as a way to appeal to younger visitors, though the guides also serve those with visual impairments in that they provide detailed commentary and mapping functions, allowing visitors to pinpoint their exact location in the museum. Additionally, the San Francisco Airport (though not a museum) is one of the first institutions to test beacons, which connect to a Smartphone app, to improve accessibility for people with visual impairments. The beacons guide blind visitors through the facility by verbally announcing locations and directions. As beacon technology is still relatively new, its use in museums is still developing. Several museums such as the Brooklyn Museum and New Museum in New York and the Leicester Castle in England are also starting to experiment with beacons by informing visitors what artwork is nearby and providing related audio content. Furthermore, the Leicester Castle is starting to experiment with ways that the technology can be adapted to be more visually impaired-friendly. Other museums should consider adopting such a strategy in order to enhance accessibility services in a similar manner.

That’s not all. Have you ever imagined being able to touch a priceless piece of art? Canadian Company Verus Art makes this experience – one that I am dying to try – possible for museumgoers with visual impairments. The company uses 3D scanning technology to produce a scan of the original work, then sends the digital file to Ocré, a printing company in Holland, to print a 3D replica containing hundreds of layers. The technique allows people with visual impairments to use their fingers as their eyes, exploring the nooks and crannies of timeless works of art in ways that would not be possible through auditory descriptions alone.

Similarly, in an effort to make its collection more accessible to visitors with visual impairments, the Manchester Museum uses haptic interfaces to allow museumgoers to explore 3-dimensional objects in a digital format. The haptic interface uses touch-enabled computer systems and a tactile feedback stylus: visually impaired visitors navigate the system by holding a stylus that has a ball on one end. The ball on the end of the stylus interacts with a ball on the screen, which responds to the stylus’s movements. When the ball on the screen connects to an object, the user feels a resistance, helping them to locate objects and enabling closer examination. The interface, which is designed for visitors that may have difficulty seeing objects in a display case but are not necessarily blind, thus allows visually impaired visitors to explore objects using their sense of touch.

Why is Accessibility Important in Museums?

An accessible museum is one that welcomes people from different backgrounds, geographic locations, and income levels, which includes people that are differently abled. According to the 2012 Census Bureau, nearly 1 in 5 people in the U.S. have a disability, or roughly 19 percent of the population. This represents a huge portion of the population; in fact, the U.S. Department of Justice estimates that museums that invest in the resources to remove barriers from their facilities and design exhibitions to be more accessible could potentially attract over 50 million Americans with disabilities.

Moreover, from a philosophical standpoint, making museums accessible is vital to improving a museum’s public trust and accountability. According the American Association of Museums, a museum should not only strive to be inclusive by complying with accessibility laws and regulations and offering opportunities for diverse participation, but should also demonstrate a commitment to providing the public with both physical and intellectual access. Nilofar Shamim Haja, Communications Officer for Rereeti, a non-profit organization based in India that strives to transform museum spaces to increase visitor engagement, explains that inclusivity in museums is crucial in a society that values access to culture as equally important as getting a degree, seeking jobs, voting, and traveling. Haja writes:

"You may argue about the cost factor and resource intensiveness of implementing a feature for a group that might only comprise a few hundred visitors. But that’s precisely what inclusion underlines: being inclusive as a society necessitates that we take into consideration the needs of the minority, the disenfranchised and those who aren’t privileged."

Thus, cultural access is not so much a privilege, but rather a fundamental right. Museums, which are largely non-profit organizations, are open to the public and therefore have a responsibility to provide cultural access to all members of society. Henry Evans refers to this as a “democratization of culture:” by providing greater access for those that are differently abled, museums can help to improve the lives of thousands of people that have previously been left out of such cultural experiences. Evans adds, these experiences “make our lives richer by giving us more options.”

These tools, and many others, are just one step in achieving full accessibility and inclusion in museums. For this to happen, museums need to have an increased understanding of the communication needs and styles of people with disabilities. It is equally important to remember that art can be experienced in many different ways, and that museums have a responsibility to provide experiences that are accessible to all. Though there is still a long way to go in making museums fully accessible, technological tools such as telepresence robots, vlogs, mobile apps, 3D scans, and haptic interfaces can help people with disabilities tailor their museum experience to meet their individual needs, ultimately creating greater opportunities for deeper engagement.

Banner image by Jonathan Nalder; in-text images by RogDel and Audrey Defretin, respectively. All images licensed under Creative Commons.