Figure 1: Front Cover of The Creativity Code, design by Chrissy Kurpeski.

Source: Marcus du Sautoy. The Creativity Code, Cambridge: The Belkap Press of Harvard University Press, 2019.

Marcus du Sautoy, a British mathematician, wrote The Creativity Code, a thought-provoking book that examines the nature of artificial intelligence in the creative industries. The Creativity Code explores AI in art, mathematics, gaming, music, and writing. One question persists throughout: “Can AI complete creative tasks better than humans?” Though du Sautoy never gives a definitive “yes” or “no,” he offers an opinion while inviting readers to form their own from the information presented. The book is thorough and easy to read, a difficult task considering the topic. As a bonus, he includes an Easter egg – one of the sections in the book was written by AI - which he challenges readers to find.

The first chapter of The Creativity Code gives a brief history and overview of artificial intelligence, easily understandable even to a novice of AI. Du Sautoy introduces two critical theories that permeate the world of AI: The Lovelace Test and the Turing Test. The Turing Test, named after the famous code-breaker Alan Turing, said that a computer may be considered intelligent if someone communicating with it cannot distinguish it from a human. Du Sautoy posits the Lovelace Test better measures success of artificial intelligence. This test, first proposed by another 19th-century British mathematician, Ada Lovelace, says that “an algorithm has to produce something truly creative” to be considered intelligent; after all, a marker of humankind is the ability to create.

In the chapter two du Sautoy introduces the three measures that he used in assessing AI’s creativity:

1. exploratory,

2. combinational,

3. transformational

This last category, transformational creativity, is the most difficult for any algorithm to achieve because it involves a total shift in perspective by dropping constraints. Du Sautoy suggests algorithms can be programmed to think outside the box and overcome their own constraints, however. Throughout the book we are presented with several compelling examples of algorithms that have attained the “mysterious and elusive” transformational level of creativity.

Figure 2: Turtle or Rifle? Source: “Fooling Neural Networks in the Physical World with 3D Adversarial Objects.” LabSix.org. 31 Oct 2017. Accessed 13 Oct 2019.

One example is AlphaGo, an algorithm written to play the highly intuitive Chinese board game Go, that played the international Go champion and won two games before losing the third. Then the algorithm learned for itself from its mistake and won the remaining rounds. The key takeaway was that the machine was able to move past the limits of its code by learning from interactions. Of course, what an algorithm learns is another kind of constraint. AI initially learns through data that is fed to it, then from data gained through interactions. Therefore, faulty data equals faulty AI. In the next few chapters, du Sautoy explores challenges with data used in machine learning and computer vision.

The chapters on machine learning were perhaps the most interesting. Du Sautoy makes several critical observations about data sources used in training AI. One is that human biases and blind spots easily work their way into data sets without the creators realizing it, like the voice-recognition software that couldn’t recognize women’s voices, or passport photo booths that recorded Asians as having their eyes closed. In these cases, data was reflective of its creator, but not of the world in which they were being used. Du Sautoy also gives examples of how data can be manipulated to trick algorithms. Researchers at Google created a 3-D turtle that AI sees as a rifle due to an imperceptible overlay placed on it (figure 2). Du Sautoy talks about how dangerous this is: “Given that driverless cars use vision algorithms to steer…imagine a stop sign that had [an overlay] put on it, or a security system run by an algorithm that completely misses a gun because it thinks it’s a turtle.” These are serious issues in machine learning that need to be resolved before we let AI take the reins.

Figure 3: Examples of images generated by an algorithm shown at the Art Basel show in 2016. Source: Ahmed Elgammal, et al. “CAN: Creative Adversarial Networks Generating “Art” by Learning About Styles and Deviating from Style Norms.” Arvix.org. 21 June 2017. Accessed 13 Oct 2019.

In the next few chapters du Sautoy delves into AI in the visual and performing arts. Du Sautoy talks about how difficult it is to obtain enough data to train an algorithm to make art. Algorithms are trained using massive amounts of data sets, and the Old Masters produced a relatively small amount. The same issue arises in music – a team trying to train AI on Bach chorales were limited to the 396 that he produced, much lower than the millions of datasets machines are normally trained on. The data is too limited to create a machine that can reproduce those styles perfectly.

The obvious solution is to train AI using a wide variety of artists so that it can create its own style, rather than perfectly replicating “The Greats.” A team at Rutgers University tried. by creating a pair of algorithms, training them on a wide array of art so that the algorithms could produce paintings. Some of the contemporary pieces that the algorithm created were displayed at the art show Art Basel in 2016 (figure 3). Visitors rated them higher and “more inspiring” than the human created art. Although this is impressive, one must question if it is truly artistic as it does not achieve transformational creativity. The algorithm combines different art, but still follows a formula. Sautoy asks us to consider the purpose of art – is it purely an “expression of human free will”? If so, computers can never create art since they can never be human.

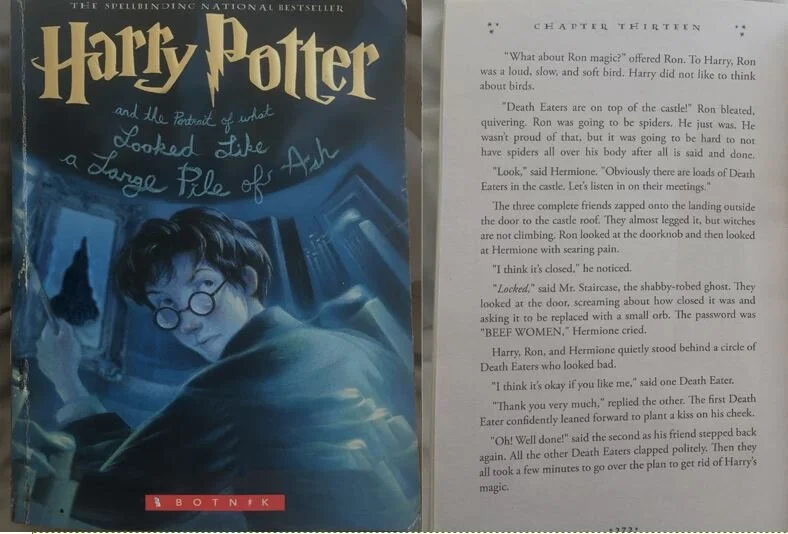

In the final chapters of The Creativity Code, du Sautoy takes on AI in writing and mathematics, two themes which are near and dear to him as a mathematician and writer. In these last chapters, he firmly voices his opinion that AI is a tool for creativity, and not creative in and of itself. For example, algorithms can discover new mathematic functions, but these functions are so overly complex that only another computer can understand them. The functions produced that can be understood by humans are simply not interesting. As for writing, du Sautoy makes the case that algorithms excel at writing conceptual pieces, like modern poetry, since the reader brings their own meaning to such pieces. But, asking AI to write a coherent novel has led to some pretty entertaining, if not good, results. Take this example of a novel written by an algorithm trained on the Harry Potter series (figure 4):

Figure 4: Front cover and excerpt from Botnik Harry Potter. Source: “Botnik Harry Potter.” Botnik.org. Accessed 10 Oct 2019.

Du Sautoy writes, “I think it’s fair to say that novelists are not likely to be pushed out of their profession anytime soon.”

Overall, this book is an excellent choice for those who want to gain a basic understanding of where AI came from and where it is headed. The author’s writing is easy to follow, and it’s detailed enough so that readers walk away with foundational knowledge of the subject. Du Sautoy offers his opinion but doesn’t force it on the reader. He makes compelling arguments that AI is a great tool for creation and catalyst for ideas, but claims it is not a creative entity. At least not yet.

References

Cornwell, Lauren. “Considering Biases in AI and the Role of the Arts.” AMTLab.org. 7 March 2019. Accessed 5 November 2019. https://amt-lab.org/blog/2019/3/a-meeting-of-the-minds-exploring-intersecting-issues-between-art-and-artificial-intelligence?rq=bias

“How the Arts are Harnessing the Power of Artificial Intelligence.” AMTLab.org. 27 May 2019. Accessed 5 November 2019. https://amt-lab.org/blog/2019/5/26osfu5um8vb1wceleosb6v98rzs64?rq=ai%20in%20the%20performing%20arts

Bringsjord, Selmer, Paul Bello, and David Ferrucci. “Creativity, the Turing Test, and the (Better) Lovelace Test.” 27 March 2001. Accessed 5 November 2019. http://kryten.mm.rpi.edu/lovelace.pdf

Du Sautoy, Marcus. The Creativity Code: Art and Innovation in the Age of AI. Cambridge: The Belkap Press of Harvard University Press, 2019.