The grant economy is an enormous arena in which persuasion, data, and human judgment drive real financial impact. Institutional grant-makers hold a tremendous amount of capital - and the associated power that comes with it. As of 2018, Harvard Kennedy School’s Global Philanthropy Report noted that there are more than 260,000 foundations across the globe which collectively hold over $1.5 trillion in assets. Annual expenditures for these foundations top $150 billion and over 90% of foundations are considered independent.

It goes without saying that the grant-market created by these foundations is globally significant and growing. While different approaches to distributing assets exist across the foundation landscape, by far the most traditional and widespread approach to allocating capital remains the grant, with 100% of surveyed foundations in the United States reporting grant-making activities to nonprofits.

As a result, there is an entire economy of labor employed in crafting winning grant applications. An organization’s institutional fundraising team (or often individual) engages in multiple types of work, effectively assuming the role of accountants and economists when preparing the budget and translating the numbers into programmatic needs, explaining the program and institution’s importance. They also act as professional writers when putting together the ultimate grant narrative, conveying the fundamental theory of social change brought about by the project, often within a tight word count.

None of this comes as a surprise for those with experience in the nonprofit sector. As one of the main mechanisms used by governments and foundations in philanthropic change-making, the humble grant has given rise to an entire industry in the nonprofit workforce ranging from grant writing and foundation-research to development consulting services.

Because of this, the grant narrative has become, perhaps, one of the most high-stakes tools of communication in the nonprofit fundraising space. Crafting the grant application involves a delicate interplay of reason, ritual, and poetry, resulting in a powerful piece of economic persuasion. $150 billion in global expenditures are more or less driven by this narrative network, giving shape to the institutions and societies in which we all operate.

The COLLECTIVE RITUAL OF MEASURING THE ARTS

The arts are some of the most idiosyncratic nonprofit organizations in the field. Typified by a large number of smaller, localized organizations, the arts lack significant government regulation, and therefore, lack large-scale coordination across the sector. This individualism is part of what makes the arts so important for their local communities, giving rise to a shared identity and culture. It is, unfortunately, also a condition that hinders their collective analysis and valuation when they are required to justify their particular existence to potential donors and stakeholders, including foundation boards.

This gap in justification has been discussed for many years, with different views shaping the priorities of grant-making institutions like arts councils and foundations. Social justifications for the arts have spanned a broad array of approaches from the purely aesthetic to the purely economic, from the impact of the arts on health and wellbeing to social bonding and community development.

Perhaps the great difficulty in agreeing on any “grand narrative” for the arts' place in society is due to this multiplicity. The arts are capable of generating economic stimulus while also bringing together communities, improving physical and mental health, preserving and disseminating cultural heritage, all while facilitating engagement with beauty.

This constellation of narratives arises from a complicated interaction between grantors and grantees in which funder values shape which organizations and projects receive funding, and grant writers responding by adjusting their narrative approaches to appeal to funders.

FUNDER VALUES: NORMATIVE JUSTIFICATION

Funder Justifications For The Arts

Image Source: Author. Informed by (Feder, 2020)

Normative justification can best be understood as the underlying reasons supporting certain actions or values. In the context of arts organizations, normative justification may be found in a variety of fundraising and advocacy activities and can often become highly visible in the grant narrative.

Given the decentralized nature of the arts paired with their broad diversity of forms, it is important to understand how certain justifications perform with certain funders and know the best approaches for different art forms and organizations.

Researcher Tal Feder (2020) investigated patterns of normative justifications in public art funding in Israel, analyzing government grant applications and their resultant funding from 1999 through 2011. They discovered significant relationships between attendance and funding, deeply shaped by the arts organizations in question.

Their work reveals three distinct normative justifications implicit in public funding for the arts: romantic, didactic, and classical justifications.

-

Values the art form in and of itself, without any external validation necessary.

Research Findings: Changes in organization attendance demonstrated no statistically significant gains or losses in public funding year-to-year, with funding similarly not changing attendance. This effect was often present in small and culturally significant art forms like dance troops. This demonstrates how the romantic approach to funding the arts values the existence and perpetuation of the form regardless of scale or consumer demand.

-

Values the arts based on their utility —as instruments for social change or impact. In this manner, art is valued mostly for its effect on the broader society.

Arguments based on building national or community identity, peace, cultural diplomacy, or community development all have potential to operate within this idiom. Broadly, justifications of art that “regard art as having a positive social influence” typically suit this approach.

Research Findings: Increases in attendance were seen after initial increases in government funding, evident primarily in culturally important symphonic organizations.

-

Values art based on its social demand, viewing art as an inherent leisure activity which should be subsidized.

Art funded in this mindset may value the arts for its ability to provide entertainment, leisure, or social welfare.

Research Findings: Organizations reporting increases in attendance significantly correlated with subsequent increases in funding in the study, reflecting the state’s consideration of consumer demand in their decision to subsidize the form. This framework was commonly seen in theatrical organizations.

Highlighting different cultural attitudes toward the arts, these three explanations reveal that it might not always be beneficial for all art forms to advocate using common strategies, and that arguments in grant narratives rooted in attendance, community engagement, or aesthetic excellence may have varying degrees of success depending on the social position of the organization and the values expressed by the funding body.

GRANTEE APPROACHES: NARRATIVE STRATEGIES

Once revealed, funder values can measurably impact the approaches taken by applicants. Changing approaches, structures, and socio-political values expressed through grant programs have shaped approaches to grant writing over time, with noticeable cases in the arts.

Analysis of grant proposals provides great insight regarding not just funder values but also how funder norms can affect the justification strategies used by artists and arts organizations themselves. Research studying grant narratives provide a form of “distant reading” which can shed light on broad social arguments for the arts, their evolution, and their effectiveness at securing funds.

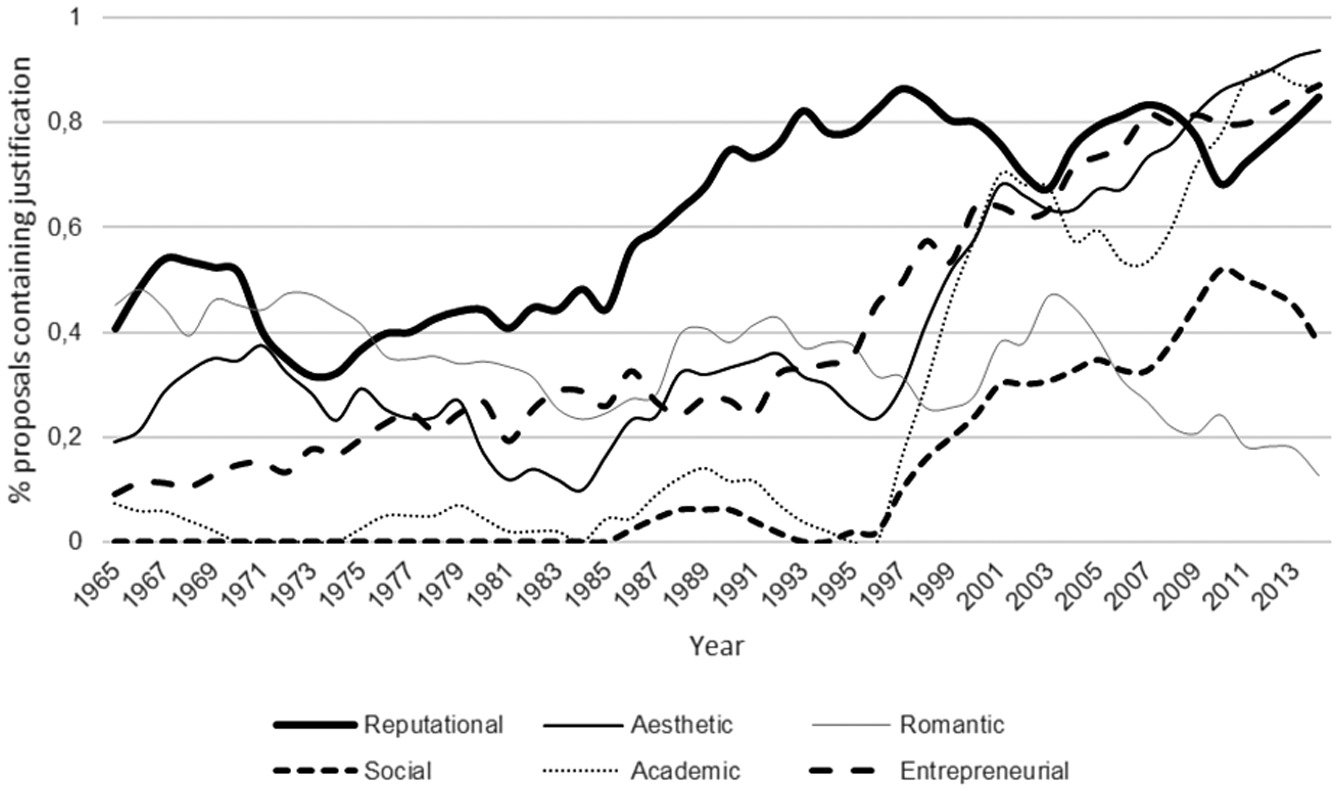

Findings out of the British Journal of Sociology (Peters & Roose, 2020) illustrated long-term changes in the content of government grant proposals made by visual artists in Belgium. Studying 494 grant proposals between 1965 and 2015, the researchers categorized six varieties of justification used by artists, divided into two larger categories of autonomous (esthetic, romantic, and reputational reasons) and heteronomous (social, academic and entrepreneurial) approaches informed by Pierre Bourdieu’s concept of field theory.

Directly citing Feder’s work with normative justification, the researchers attempt to measure how positions taken towards artistic legitimacy by cultural policymakers indirectly affects language used in artistic grant proposals, altering an artist’s written narrative to best fit within the values of the funding body and, ultimately, win funding.

Simple five-year moving average of the six justifications, 1965-2015

Image Source: Peters & Roose, 2020

Notably, the research finds that as the Belgian state began to introduce greater structure and bureaucracy within their grantmaking apparatus, that autonomous justifications centered on romantic notions of art declined while heterogeneous justifications based on reputation, social impact, and entrepreneurship saw significant growth.

The research also notes an increase in combination of approaches used, signifying a growth in multifaceted justification strategies made by artists. Triggered by the formalization of state grants in the 1990’s, this coalescing demonstrates a pragmatic response by artistic grantees to the altered economic conditions while also strategically targeting the new social preferences of cultural policymakers. While their proposed art forms remained largely the same, the appeals noticeably changed in response.

Therefore the grant market can now be understood from both sides: what gets funded in the first place reveals the implicit assumptions held by grantors toward art. The grantee then responds and anticipates this set of values through altered approaches to justification in their proposals.

Thus, we can see the entire system as a matching game, with narrative justifications shifting in attempts to “click” with the similarly ever-shifting values of funders in order to craft a successful pitch. Funders shifting preferences over time dictate both the measurements they seek as well as their normative justifications used by artists and organizations.

Knowing how to discern these various signals exhibited by funders can be vital to informing a successful grant narrative. By shaping narratives in the best fit for the grantor’s values by way of selecting the appropriate data and arguments, grantees can build cases on the most strategic ground.

ART AS DATA - WORKING AROUND METRICS

Michelle Forrest (2011) proposes an additional approach to justifying the arts - aesthetic explanation involving “embodiment” - inviting the viewer to truly feel the impact (in Aristotelian terms - catharsis) of the work.

Their research, written from the perspective of funding for arts education, takes a multidisciplinary approach to understanding how artists and organizations justify their work, citing philosophical issues with aesthetics at large. Aesthetics, as a field, has no grand question outside of defining and recognizing beauty. Unlike other fields such as ethics, aesthetics does not inform us of how to live, how to act, or provide answers to any operating conditions of the world. This presents a difficulty in defending the arts on any form of non-aesthetic grounds since, while the arts may provide for positive economic or health benefits, for instance, it is rarely the best or most efficient way to deliver these social goods when considering industries beyond the arts.

Forrest’s answer to this disadvantage is the use of aesthetic means in the justification itself as opposed to sequestering it solely as the object of justification.

““In justifying the arts our efforts need to be aesthetically expressive, thereby engaging in that which they claim offers this effect.” ”

Citing Wittgenstein, Forrest argues that the aesthetic explanation is not a causal one, but a “‘new account of a correct explanation. Not one agreeing with experience, but one accepted” thereby presenting new perspectives or compelling realities previously unconsidered.

While these approaches are broad in concept, they can become highly particular in application depending on the organization seeking funding. When grant makers allow submission of supporting documentation in the form of images, video, and audio, the arts have unique opportunities to display the aesthetic aspects of their work in their fullest embodiments. This attention to documentation paired with various advances in arts-based research methods — which fuse social scientific research and artistic practice —provide a variety of methods for creative expression to be used as its own datapoint, allowing art to potentially defend itself without sacrificing its salience.

Case Study - Hypothetical String Quartet

Putting these theories together, we can illustrate this grant-matching game as a strategic thought process for grantees:

In tandem with this exhibition-focused approach, weaving in arguments highlighting social impact, reputation in the community, and even the entrepreneurial nature of the Quartet may shore up the appeal. Ultimately, many justification strategies can exist in one narrative and positively reinforce each other, but keying into a funder’s particular value structure helps prioritize the overall approach of the argument.

With the rise in Generative AI software and its impact on fundraising, it is vitally important for grant writers to understand the importance of their narratives and instances where AI may, or may not, be a wise choice to deploy. AI tends to produce average outputs, particularly regarding text. While effective for boilerplate memos or internal write-ups, appealing to outside funders necessitates critical thinking in crafting a narrative. Therefore, automating too much of this process carries a risk of standardizing an application as opposed to highlighting an organization’s unique attributes in connection with the funder’s values.

CONCLUSION

Considering this preponderance of language, argument, and case-making in the grant economy, the broader dynamic of this industry might be seen as a macrosocial conversation. In the absence of price competition, as in typical commodity markets, competition arises in a grantee’s ability to participate in these institutional conversations, forming a kind of ritual ceremony on organizational scales. Understood this way, $150 billion annually is moved by words and logic, underscoring the sheer significance of effective grant-writing for a nonprofit organization’s survival. Not only are the justifications used in these high-stakes conversations important for the particular success of grantees but also reveal just how powerfully the narratives and values held by funders shape these conversations, driving institutional negotiations of social and economic order within the arts.

-

Alasuutari, Pertti. “Conversation Analysis, Institutions, and Rituals.” Frontiers in Sociology 8 (October 10, 2023). https://doi.org/10.3389/fsoc.2023.1146448.

Bordieu, Pierre. “The Field of Cultural Production: Essays on Art and Literature”. New York :Columbia University Press, 1993. https://archive.org/details/fieldofculturalp00bour/mode/2up

Dimaggio, Paul. “Measuring the Impact of the Nonprofit Sector on Society Is Probably Impossible but Possibly Useful.” In Measuring the Impact of the Nonprofit Sector, edited by Patrice Flynn and Virginia A. Hodgkinson, 249–72. Boston, MA: Springer US, 2001. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4615-0533-4_15.

Feder, Tal. “Normative Justification for Public Arts Funding: What Can We Learn from Linking Arts Consumption and Arts Policy in Israel?” Socio-Economic Review 18, no. 1 (January 1, 2020): 193–213. https://doi.org/10.1093/ser/mwy001.

Forrest, Michelle. “Justifying the Arts: The Value of Illuminating Failures.” Journal of Philosophy of Education 45, no. 1 (February 1, 2011): 59–73. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9752.2010.00771.x.

Johnson, Paula. “The Global Rise of Structured Philanthropy.” Harvard Kennedy School Center for Public Leadership, Page 10. 2018. https://www.hks.harvard.edu/sites/default/files/2023-09/global_philanthropy_report_final_april_2018.pdf

Nonprofit Tech for Good. “The Best AI Fundraising & Productivity Tools for Nonprofits,” June 21, 2024. https://www.nptechforgood.com/2024/06/21/the-best-ai-fundraising-productivity-tools-for-nonprofits/.

Peters, Julia, and Henk Roose. “From Starving Artist to Entrepreneur. Justificatory Pluralism in Visual Artists’ Grant Proposals.” The British Journal of Sociology 71, no. 5 (2020): 952–69. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-4446.12787.