By: Taylor Lien

introduction

Talk to almost anyone in proximity to entertainment right now, and they’ll bemoan the current state of affairs. Contractions, post-strike shocks, and a host of shifting terrain in the system, from AI to video production, suggest a relative dark age compared to the ‘peak tv’ era of the last decade or so. The current era of television feels most like the decade preceding ‘New Hollywood’ in the 1970s, the fall of big budget movie musicals and an industry wide scramble to find out what comes next. Television is in some ways returning to the old model with commercial breaks and digital bundles, but television as a medium and an industry has been forever changed by the birth of prestige television. The lessons that are learned from this time will likely dictate the next fifty years of American television.

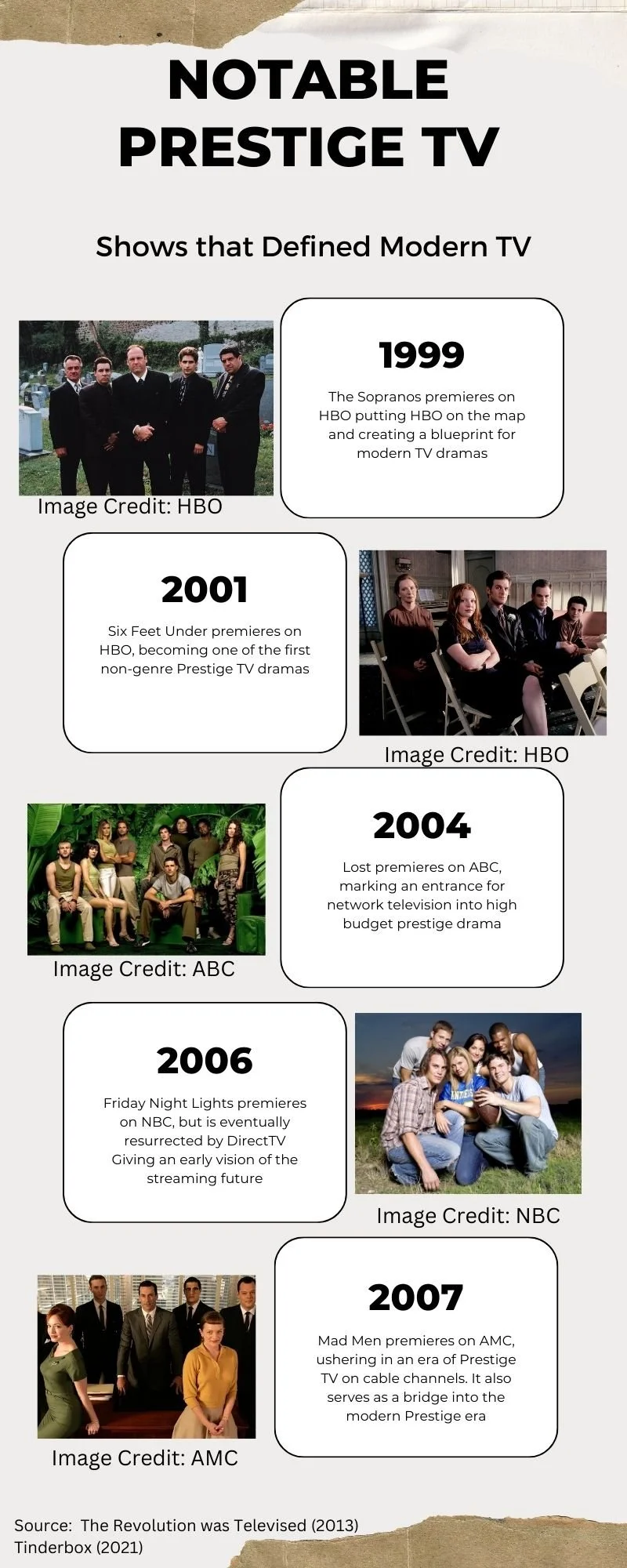

Prestige television as a concept is hard to define, and is now much more often applied retroactively instead of proactively. Because of the temporal nature of television, it is much easier to see the impact of a series in hindsight rather than as it airs. Early HBO juggernauts like The Sopranos or The Wire have come to stand as the early definition of prestige TV, but at the time they were much better known for their crude language and blatant nudity. Creator David Chase himself said, “I didn’t think that ‘The Sopranos’ would chart any kind of new course, all I wanted to do is just get as close to cinema as I could.” (Enger, 2019)

The ‘Formula’ for Prestige Dramas

Image. The Thirteen Rules for Creating a Prestige Drama, Source: Hill, Vulture, 2017

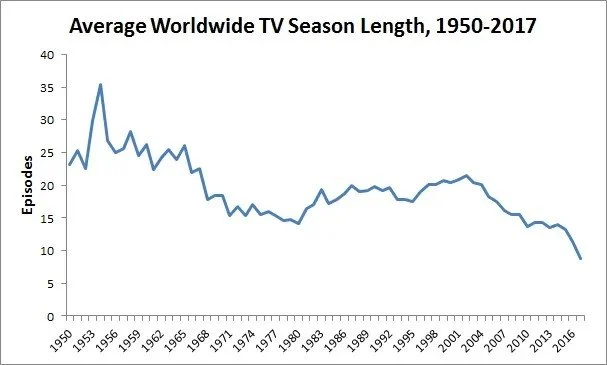

The things that have come to define prestige TV in this modern era are shorter seasons, high production value, and sometimes A-list stars. This attitude towards television has come to not only define prestige television, but arguably most non-network or streaming shows. Streaming once promised a freedom from the time bounds and content restrictions of network television, and yet there are these invisible restrictions that have come to define a majority of Netflix, Amazon and AppleTV originals.

In an age where television and film can be accessed on the same platform in the same ways, the artistic lines between film and television seem more blurred than ever. With television having higher budgets, bigger stars and shorter seasons, television as a medium has gained a prestige never seen before. The phrase prestige television has modern connotations, being coined in the last decade, by a combination of online culture writers and industry professionals. Yet, the industry has adopted many of the practices of prestige television across streaming television of all audiences, budgets and levels of prestige.

Prestige TV is a concept barely acknowledged or uttered outside of television and entertainment criticism spaces. Even some of the most seminal books on the subject, seem to go out of their way to avoid using the word. Yet it is thrown around frequently in online spaces, and online culture publications like Vulture. In 2013, Vulture posted a list of the rules to creating a prestige show, (Hill, 2013). In the decade since that article was published, it seems the ‘rules’ around prestige television have blurred.

Infographic created by author.

In 2017, VanArendonk published a follow up to the original Vulture article, identifying signs you are watching a prestige drama. (VanArendonk, 2017) VanArendonk identified the patterns in the television dramas that came to qualities of the long-form storytelling within a short form medium, as TV became and has become more and more serialized.

VanArendonk notes how the signs pointed out the ways TV stretches to fit the container it is within. Streaming changes those assumptions. In the streaming era, that means imagining the TV binge as a 10-12 hour movie instead of a weekly check in with your favorite characters. As Sepinwall puts in the updated epilogue of his book The Revolution was Televised, the thing that television has an advantage over film is time. (Sepinwall, 2015) When television was mostly watched in a linear format, and availability to watch a new episode beyond its original airing was limited, the storytelling mode of TV matched that delivery. (Edwards, 2024) As television grew more digital, things like DVRs, and DVD TV boxed sets allowed for viewers who did not catch the episode in its original time slot to catch up. This allowed for the writers and creators of TV to write storylines that spanned entire seasons instead of entire episodes. Television grew into a more complex, time-bound medium. Shows evolved over years, and even over the moving of networks. Friday Night Lights is often pointed out as one of the earliest modern examples. Starting out as a show airing on NBC primetime, it moved over to DirecTV’s early proto-streaming model, and finished its run with support from NBC. (The Ringer, 2024)

Yet, with the rise in popularity of the binge model of viewing, enabled by early streaming shows like Orange is the New Black and House of Cards on Netflix, the wait is big, usually the one between seasons not between episodes. When television shows or miniseries are discussed as ‘eight-hour movies’ the thing rarely mentioned is the sheer amount of plot and character development in those eight hours. The time given to tell these stories is fundamentally different from film as a medium, and the economy with which film develops characters and plots is designed to be consumed in one, or in the case of Oppenheimer, possibly two sittings.

A show that drops all its episodes at once can enjoy a strong cultural conversation online for a few weeks at the most, but when held up next to shows like Succession or Twin Peaks: The Return the fundamental nature of those stories unfolding week after week, and the discussion that ensued, feels crucial not only to their success, but their lasting cultural legacy. Ben Travers in his reporting from 2017 on the revival series, called out the way that “Lynch is teaching us to watch TV differently.” That was 2017, and the television landscape has in some ways come back around to the wisdom of week to week releases. In many ways, that is the underpinning of much of the recent developments in television, the disruption of the early days of Netflix and the streaming wars has given way to the reluctant return of the old ways of being with the supplement of new technologies. (Travers, 2017)

The defining feature of those early seminal dramas on HBO and AMC was the time given to complex characters over time. Which begs the question, with the number of scripted series peaking in 2023, (Koblin, 2024) why are fewer and fewer of those shows getting the time necessary to tell those stories. One does not need to look further than two of the Emmy darlings from the 2023-2024 season, The Bear and Succession, to see this problem in sharp relief. The second and final seasons of both The Bear and Succession respectively only had a meager 10 episodes. Their popularity demonstrates that a lot can be accomplished in those few episodes, but no one would argue that shows operating on that level don’t come along all the time. In the introduction of his book, James Andrew Miller argues that “HBO transmogrified television.” (Miller 2021) When looking at the modern day television landscape, it is hard to not see what he means. Higher budgets, shorter seasons, and bigger stars are all markers of critically praised television in 2024.

Prestige TV has almost become a genre unto itself, not unlike the idea of an ‘Oscar Bait’ movie. With television going through a contraction, it remains to be seen what elements of the Peak TV era will come with it. Many argue TV will go back to its roots, veer towards less experimental and more traditional television. (Loofbourow, 2023) The recent success of things like Abbott Elementary and the rise of rewatching shows like Gilmore Girls, Suits and Grey’s Anatomy, do suggest a hunger for more ‘traditional TV storytelling.’ (Porter, 2023)

In an ideal world, both types of television could exist in the streaming landscape. Arguably, that was the original pitch of streaming entertainment as a concept. Whatever you want to watch is served to you via algorithm, and when Suits is stated as the number one streamer for Netflix for 12 straight weeks, it demonstrates a demand for more than heady, expensive and often difficult to watch ‘prestige TV.’ While the Emmys are by no means a completely objective measure of the best television made in a given year, award show recognition is often the thing that these prestige shows are wanting, how the shows nominated for Emmys stack up viewership wise can give insight into how popular prestige television shows actually are. A study done in fall 2022 by The Entertainment Strategy Guy drew comparisons between the most watched streaming shows and those nominated for Emmys.

Image: Top 20 Series since 2021 (Entertainment Strategy Guy, 2022)

Conclusion

Other than the outlier of Stranger Things, a majority of the Emmy nominated shows did not make the top 20 most streamed series. Winning an Emmy may boost the profile of a TV series, but in the time period shown here shows like The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel were nominated for their fourth season, and are fifteenth in most streamed shows of that period. The data demonstrates that the disconnect between what television is most popular and widely watched does not really correlate with award-winning or ‘prestige television.’

Yet, I would argue a failure of the ‘Peak TV’ and prestige TV eras was promoting the idea that these experimental, format-forward shows were intended for wide consumption. With the rise of streaming, also came the death of ratings and traditional metrics for success. Most prestige TV shows, if the ratings were not obscured, never even dreamt of reaching the heights of network television viewership. Even when compared against the most successful finales of HBO’s own stable, Succession maintained a relatively niche viewership. (Pequeño IV, 2023) The cultural weight of that show, especially in online spaces, would give the perception of high viewership numbers, but in actuality, the most watched shows on a week to week basis may be ones you’ve never seen or heard of before. A single episode of S.W.A.T on CBS can gain more viewership than the finale of a show as beloved as Succession. (Mitovich, 2024)

TV, unlike almost any other creative medium sitting at the intersection of art and commerce, responds to cultural trends in a way that the pace of filmmaking can never match. There is no shortage of those who want to predict where television is headed next, but considering television is a medium that unfolds over time, it seems to me the best idea is to wait and see what the next season holds.

-

Egner, J. (2019, January 7). David Chase on “the Sopranos,” trump and, yes, that ending. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2019/01/07/arts/television/david-chase-sopranos-interview.html?login=email&auth=login-email

Edwards, P. (2024, March 17). How TV went from bad to great. YouTube. https://youtu.be/kvWh_cgiuZg?si=UtMxYFXdsvlvHWEA

Guy, T. E. S. (2022, September 14). Were the TV series nominated for Emmy Awards “popular”? Entertainment Strategy Guy. https://entertainmentstrategyguy.com/2022/09/14/were-the-tv-series-nominated-for-emmy-awards-popular/

Hill, L. (2013, May 15). The 13 rules for creating a prestige TV drama. Vulture. https://www.vulture.com/2013/05/13-rules-for-creating-a-prestige-tv-drama.html

Jensen, J. (2017, September 12). “Twin peaks” finale recap: “the return” passes away on its own terms. EW.com. https://ew.com/recap/twin-peaks-season-3-finale/

Koblin, J. (2024, February 9). Hollywood made 14% fewer shows in 2023, marking the end of peak TV. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2024/02/09/business/media/peak-tv-shows-2023-decline.html

Lindbergh, B. (2017, August 4). Mourning the loss of the long TV season. The Ringer. https://www.theringer.com/tv/2017/8/4/16094348/inefficiency-week-mourning-the-lost-long-tv-season

Loofbourow, L. (2023, October 4). TV’s boom cycle is over. what comes after the crash? - the ... The Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/style/2023/09/27/future-of-television-peak-prestige-tv/

MILLER, J. A. (2022). Tinderbox: HBO’s ruthless pursuit of new frontiers. HOLT PAPERBACKS.

Mitovich, M. W. (2024, March 2). Ratings: Blue Bloods grows with Treat Williams tribute episode. TVLine. https://tvline.com/ratings/blue-bloods-viewers-treat-williams-tribute-episode-1235177545/

Pequeño IV, A. (2023, May 31). “succession” finale hits series-high 2.9 million viewers-but falls far behind other HBO hits and broadcast shows. Forbes. https://www.forbes.com/sites/antoniopequenoiv/2023/05/30/succession-finale-hits-series-high-29-million-viewers-but-falls-far-behind-other-hbo-hits-and-broadcast-shows/?sh=4e872a77a02b

Porter, R. (2023, October 6). “Suits” sets streaming chart record for most weeks at no. 1. The Hollywood Reporter. https://www.hollywoodreporter.com/tv/tv-news/streaming-tv-rankings-sept-4-10-2022-1235610454/

Sepinwall, A. (2015). The revolution was televised: The cops, crooks, slingers, and slayers who changed TV drama forever. Simon & Schuster.

The Ringer. (2024, January 17). Did “Friday Night Lights” Stick the Landing. Stick the Landing. episode. Retrieved April 6, 2024, from https://www.theringer.com/2024/1/17/24041048/friday-night-lights-finale-always-did-it-stick-the-landing.

VanArendonk, K. (2017, March 28). 13 signs you’re watching a “prestige” TV show. Vulture. https://www.vulture.com/2017/03/prestige-tv-signs-youre-watching.html