introduction

This study looks into the role of public art in the urban design process, seeking to provide insights as to how public art can intentionally be used in the urban design system to achieve the goal of sustainability. The overarching question of this research is what the purpose of public art is. As a strong visual piece inside cities, usually, on a comparatively larger scale, public art has a strong visual impact on the audience. Thus, what kind of information will be delivered to the audience? While the concept of sustainability, or, more specifically, urban sustainability, can be incestigated with various concentrations, it generates the question of what kind of urban planning governments or professional organizations are using to achieve specific sustainable issues. Is there any relationship between the purpose of public art and the method used by urban design for sustainable purposes?

In Part I of this study, I explored the existing connections between public art, urban planning, and sustainability in theory and in practice. This portion of the research dives into three cases studies to understand how three cities heralded for their sustainability practices are engaging the use of public art in their work. These cities are Brussels, Vancouver and Singapore. The case studies follow. The full report can be accessed here.

Image: Ai, Weiwei. Untitled Refugee Life Jacket. 2017.

Image Source: Dezeen

Case Studies

According to Tripadvisor and Green.org, based on a variety of factors including renewable energy use, public transportation, and waste management, they share the most sustainable cities in the world: Amsterdam from the Netherlands, Brussels from Belgium, Bordeaux from France, Belfast from the UK, Berlin from Germany, Copenhagen from Denmark, Galway from Ireland, Helsinki from Finland, Melbourne from Australia, Oslo from Norway, Reykjavik from Iceland, Stockholm from Sweden, Singapore, San Francisco from United States, and Vancouver from Canada (Welch, 2023) (Fernandez, 2024).

Chart created by author.

Out of the 15 most sustainable cities worldwide, all are situated near bodies of water. Additionally, 87% of these cities have one or more rivers flowing through them, while the same percentage are adjacent to seas or oceans. The size and population of each city vary, with the population density ranging from 512km2 to 27,625km2 , with an average of 9829km2.

Singapore, Vancouver, and Brussels were chosen for deeper analysis due to their geographical diversity spanning different continents. Brussels is one of the two cities that do not relate to any water from all the most sustainable cities in the world, while Singapore is located on an island, and Vancouver is a harbor city. The different locations made cities face various issues that will give broader perspectives and insights to the research.

Singapore, Singapore

Singapore is a sovereign city-state and island country located in Southeast Asia, situated at the southern tip of the Malay Peninsula (About Singapore, 2024). The country consists of the main island of Singapore and numerous smaller islands, with a total land area of around 275 square miles (About Singapore, 2024). Historically, Singapore's geographic location has played a significant role in developing its major transportation and commercial hub in the region (Singapore River, 2024).

Due to the geographic situation, Singapore experiences consistently high temperatures, with average daily temperatures ranging from 20°C (68°F) to 36°C (96.8°F) throughout the year, and the humidity in Singapore is typically high, averaging around 82% (Climate of Singapore, 2024). As a typically tropical climate, Singapore receives a significant amount of rainfall throughout the year, with two distinct monsoon seasons: the northeast Monsoon occurs from December to March, and the Southwest Monsoon occurs from June to September (Climate of Singapore, 2024).

Image: The Limits of the Singapore Housing Model

Image Source: Market Urbanism

Social and Cultural Situation

Singapore has a multicultural society that is home to a diverse population of various ethnicities, including Chinese, Malay, Indian, and Eurasian communities(About Singapore, 2024). Singapore recognizes five official languages, English, Mandarin Chinese, Malay, and Tamil, that help to form the country’s multicultural heritage (About Singapore, 2024). Due to high economic freedom, Singapore has experienced rapid economic development since its independence in 1965, transforming from a small trading port into a global financial center for technology, innovation, and commerce (Zarroli, 2015).

Even though being a multiracial and multireligious country, Singapore promotes a strong sense of civic responsibility and social cohesion among its citizens (Racial & Harmony, 2024). The concept of ‘total defense’ launched in 1984, which highlights military, civil, economic, social, and psychological defense, highlighting the importance of collective action and national unity in safeguarding the country’s security and prosperity (Total Defence Resources, 2024). Besides, Singapore has invested heavily in arts infrastructure, including world-class museums, galleries, theaters, and performance spaces (Zarroli, 2015).

Social and Cultural Issues

Despite being one of the wealthiest nations in the world, Singapore has a significant wealth gap problem. The rapid economic growth has led to income disparity, with a portion of the population enjoying high standards of living while others struggle with daily life (Ping Tjin, 2023). The Statistics Department in Singapore said income inequality hit a record low in 2020, with the Gini coefficient at 0.371 in the year 2023 (The Statistics Department, 2023). Similarly, due to the income disparity, housing affordability is another concern for many Singaporeans due to high property prices and limited space (Market Urbanism, 2020).

Currently, Singapore has one of the fastest-aging populations, with citizens aged 65 and above making up nearly one-fifth of the population (Wan, 2023). This demographic shift triggered challenges in local residents' healthcare, eldercare, and pension sustainability. Also, the Economy Head of Applied Aging Studies at the Singapore University of Social Sciences, Kelvin Tan, said that the shift in seniors' mindsets impacts Singapore's economic longevity (Wan, 2023).

As mentioned before, Singapore's social and cultural backgrounds led the city to be, and continue to be, a society shaped by immigration. Its immigration policies are strongly influenced by insecurity and economic vulnerability, which immigration remains a politicized issue and will continue to be a point of concern in the near future (Wan, 2023). It is obvious that immigrants often struggle to feel that their identities are secure and protected, which can impact racial harmony (Tan, 2014).

Environmental Issues

As an island country, the geographic location next to water made Singapore face environmental challenges such as water pollution, waste management, and sustainable resource use. (Gordon, 2014) Climate change is one of the significant environmental challenges, and there is a need to reduce greenhouse gases in the atmosphere (Overview, 2024). The government indicates that ‘In Singapore, the most significant greenhouse gas emitted is carbon dioxide, primarily produced by the burning of fossil fuels such as oil and gas to meet our energy needs in the industry, buildings, household, and transport sectors’ (Overview, 2024).

Climate change will lead to higher temperatures, rising sea levels, and changing weather patterns, and rising sea levels could lead to increased flooding and erosion along the coastlines, posing risks to infrastructure and communities (WWF-Singapore, 2024). In Singapore, there is a dense network of short streams on the island, but due to the low gradient of the streams and excessive runoff from the cleared land, there is local flooding (Climate of Singapore, 2024).

Geographically, Singapore is located in the tropics and experiences hot and humid weather all year round. The extensive urbanization and development in Singapore also contribute to the urban heat island effect, seat stress among urban residents due to prolonged exposure to elevated temperatures, and cause health issues such as heat cramps, heat exhaustion, and heat stroke (Learn about Heat Stress, 2024).

In addition, energy poses a significant challenge to achieving water self-sufficiency worldwide, and Singapore is no different (Gordon, 2014). The process of pumping water, treating raw water and sewage, as well as producing NEWater and desalinated water, demands substantial energy consumption, in particular, relying heavily on energy due to the high pressures required to extract water through membranes and remove salt (Gordon, 2014).

Sustainable Plan

Singapore's government launched the ‘Green Plan 2030’ in 2023. The Singapore Green Plan 2030 is a comprehensive national movement aimed at advancing sustainable development and positioning Singapore in environmental stewardship (Singapore Green Plan, 2024). The Green Plan outlines ambitious targets and strategies across various sectors focused on critical environmental challenges and promoting long-term sustainability. By setting concrete targets over the next decade, Singapore aims to strengthen its commitment to reducing greenhouse gas emissions and achieving a net-zero emissions goal by 2050 (Singapore Green Plan, 2024).

The ‘Green Plan 2030’ is separated into five main goals: the city in nature, sustainable living, energy reset, green economy, and resilient future, with 14 sub-detailed targets (Singapore Green Plan, 2024).

City in Nature: Singapore aims to enhance its green spaces and biodiversity, making nature more accessible to residents, targeting the development of new parks, doubling the annual tree planting rate, and increasing the land area of nature parks (Singapore Green Plan, 2024).

Sustainable Living: The Green Plan encourages a shift towards sustainable consumption and waste reduction, including reducing household water consumption and waste to landfill per capita per day (Singapore Green Plan, 2024).

Green Commutes: Singapore aims to promote environmentally friendly modes of transportation, such as mass public transport and electric vehicles that increase the share of mass public transport and expand cycling path networks (Singapore Green Plan, 2024).

Energy Reset: The Green Plan emphasizes the transition to green energy sources and improving energy efficiency, such as increasing solar energy deployment and greening a significant portion of Singapore's buildings (Singapore Green Plan, 2024).

Resilient Future: Singapore seeks to enhance its resilience to climate change impacts, such as sea-level rise and flooding. Targets include formulating coastal protection plans and building local capabilities in the agri-food industry (Singapore Green Plan, 2024).

To achieve these targets, the Green Plan outlines specific actions and milestones to be completed by 2030 and beyond (Singapore Green Plan, 2024). The Green Plan also emphasizes the importance of community engagement and collaboration (Singapore Green Plan, 2024). In addition, by involving stakeholders from government, industry, academia, and civil society, Singapore aims to foster a collective effort towards sustainability and resilience (Singapore Green Plan, 2024).

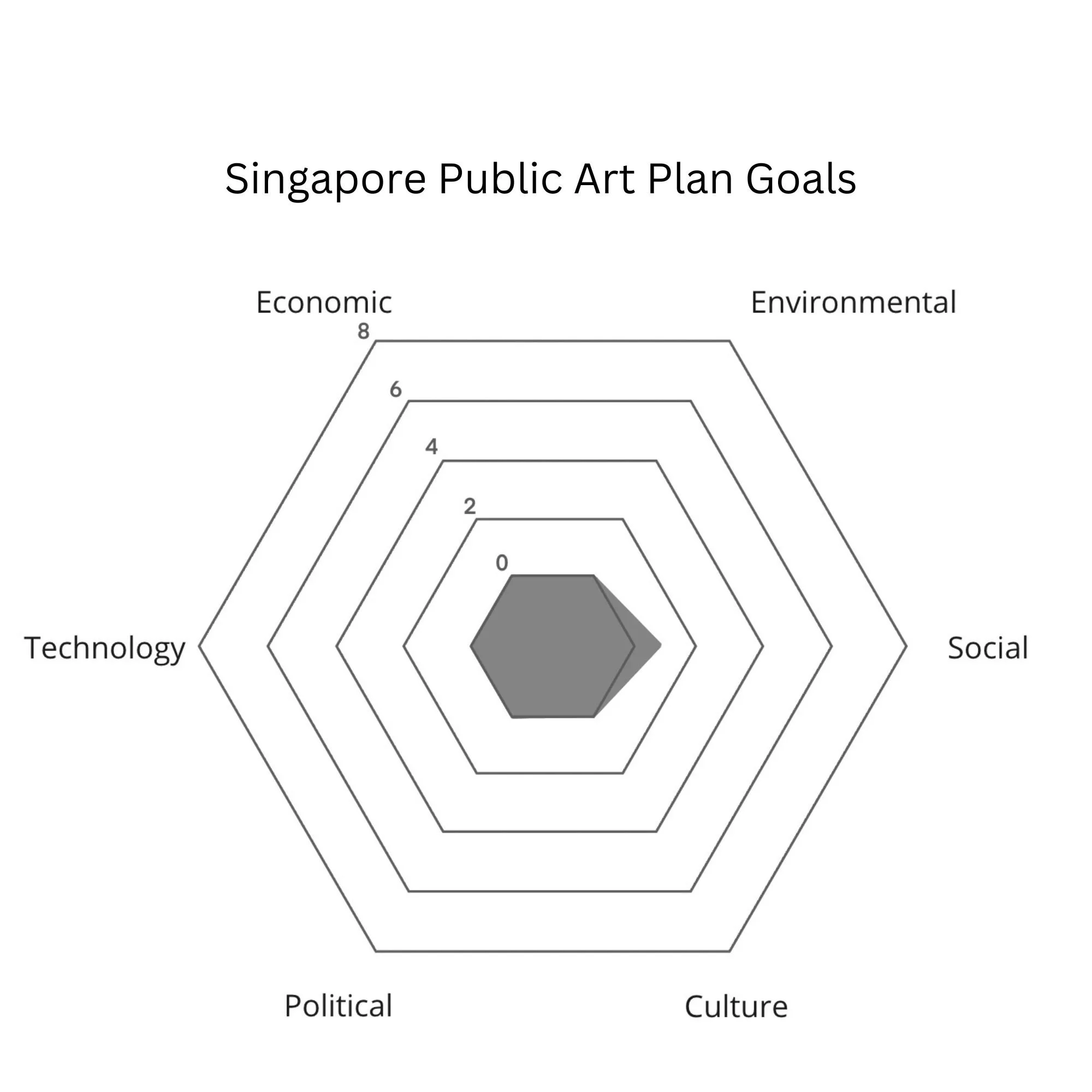

Chart created by author.

Public Art Plan

Currently, Singapore lacks a comprehensive specific plan for public art, but the government has officially introduced the SG Art Plan for Singapore covering the period from 2023 to 2027 (SG Arts Plan, 2024). The primary objective of this plan is to provide guidance for national arts and culture policies, bringing together the collective efforts of the public, private, and people sectors to address the opportunities and challenges in this rapidly changing world (SG Arts Plan, 2024).

In response to the increasingly complex social issues arising from multiculturalism, the government aims to use this art plan to foster greater social cohesion in Singapore (SG Arts Plan, 2024). Research data indicates that more than eight out of ten people believe that art and culture contribute to a stronger sense of belonging among citizens and facilitate understanding of diverse backgrounds and cultures (SG Arts Plan, 2024). Thus, ‘fostering a sense of belonging, promoting social cohesion, and developing bonds in the community’ is one of the main goals mentioned in the plan due to the unique cultural backgrounds of the country (SG Arts Plan, 2024).

Besides, the SG Art Plan highlights the significance of technology and innovation in Singapore’s art industry. The government is seeking to establish a novel business model that expands opportunities for arts professionals (SG Arts Plan, 2024). Technology plays a pivotal role in facilitating and supporting the arts sector by developing streamlined digital platforms that increase the accessibility for various groups, paving the way for greater aggregation and collaboration (SG Arts Plan, 2024).

Within the plan's framework, there is a growing emphasis on enhancing livability through art and culture. It is noted that the livability of a city is also gauged by its sustainability and resilience (SG Arts Plan, 2024). While the plan acknowledges the importance of sustainability, it primarily focuses on creating a sustainable art ecosystem that fosters a robust and diverse network of individuals, organizations, and institutions (SG Arts Plan, 2024). This ensures that art can develop sustainably, with minimal waste and efficient use of resources, but cannot solve the challenges posed by climate change and the increasing risks of extreme weather events (SG Arts Plan, 2024).

For the public art section, previously, in 2018, the National Arts Council introduced the SG Art Plan for the years 2018 to 2022. Following the guide of this plan, the National Arts Council provided support through grants and initiatives for a diverse catalog of physical, digital, and hybrid programs aimed at fostering public artworks in collaboration with artists and agencies (SG Arts Plan, 2024).

In the latest iteration of the art plan, three key targets have been identified: ‘A Connected Society - where the arts bring together 3P,’ ‘A Distinctive City – that is cultural, iconic and inspiring,’ and ‘A Creative Economy – to drive competitiveness’ (SG Arts Plan, 2024). Within the scope of ‘A Distinctive City,’ particular emphasis is placed on the development of public art, with the aim of ‘make strategic use of art spaces, public artworks, and exhibitions to invigorate neighborhoods and contribute to their unique identities’ (SG Arts Plan, 2024).

The National Arts Council acknowledges the success of the Public Spaces for Art scheme introduced under the previous SG Art Plan in 2018, which received positive feedback (SG Arts Plan, 2024). As a result, the National Arts Council has committed to collaborating with the Singapore Art Museum to formulate a comprehensive masterplan specifically for public art to achieve consistency across the whole government (SG Arts Plan, 2024).

Chart created by author.

Analysis

The target issues addressed in Singapore’s sustainable plan and public art plan share some similarities, yet they do not entirely align with each other. Previous analyses of the sustainable plan have emphasized addressing social, environmental, technological, and economic challenges, with a particular emphasis on environmental and technological aspects that align with the historical focus of public policy in Singapore.

The intersection between art and sustainability plans shows some alignment, yet there is a huge disparity in addressing the specific subgroup of public art and sustainable development. While the concept of public art is rarely mentioned in the overall plan, its role is largely limited, merely appearing twice with the single aim of enhancing awareness of local identity.

Within the plan’s framework, sustainability, technology, and economic issues are mentioned, but public art is not shown as a solution. The inherent potential of public art can extend beyond mere identity enhancement. As mentioned in the previous purpose of the public art section, it shows the capacity to serve as a powerful tool for raising awareness about environmental conservation through its educational nature.

Moreover, public art has the potential to stimulate local economic growth, not limited to just creating more collaboration with the artists mentioned in the art plan. Additionally, the integration of public art into urban spaces can simulate creativity, which is a fundamental element in driving innovation and technological advancement. When facing the problem of racial harmony, the nature of public art can also mitigate the worries and promote social cohesion among multicultural cities.

By exploring the transformative power of art, communities can cultivate a culture of cohesion, innovation, and resilience, building a unique way for urban development that aligns with the country's sustainable and artistic goals. The good news is that the Singapore government is increasingly prioritizing the promotion of consistency in fostering public art in the country. National Art Council makes a promise to bring specific public art plans to the country in the future and recognize the success of public art in the previous period.

Vancouver, Canada

Vancouver is situated on the southwestern coast of Canada, in the province of British Columbia; it is located on the mainland, near the southern tip of the province, and is bordered by the Pacific Ocean to the west and the Coast Mountains to the north (City of Vancouver, 2024). The city is built on a series of peninsulas and surrounded by water, including the Strait of Georgia to the west and the Fraser River delta to the south (City of Vancouver, 2024). Noticeable, Vancouver’s street layout is a standard grid with streets running north and south and avenues running east and west (City of Vancouver, 2024).

Vancouver has a temperate oceanic climate, characterized by mild winters, cool summers, and abundant rainfall throughout the year, benefiting from protection by surrounding mountains and the tempering influence of Pacific ocean currents that stands out as one of Canada’s milder cities due to these factors (City of Vancouver, 2024). Despite its rainy reputation, Vancouver ranks as the 9th rainiest locale in Canada (City of Vancouver, 2024). The wettest months occur in November and December, with an average rainfall of 182mm (City of Vancouver, 2024).

Image: Geography | City of Vancouver

Image Source: City of Vancouver

Social and Cultural Background

Vancouver is known for its cultural diversity, with a significant population of immigrants from various parts of the world (Cultural Diversity, 2024). Local heritage and its affiliated organizations play a crucial role in enriching the cultural, civic, and economic fabric of the society, making this multiculturalism reflected in the city’s vibrant neighborhoods (Canadian Heritage, 2023). Thus, Vancouver boasts a thriving arts and culture scene, with numerous galleries, theaters, museums, and performance spaces showcasing local and international talent (City of Vancouver, 2024). In addition, Vancouver’s natural beauty and temperate climate encourage an active outdoor lifestyle, such as hiking, skiing, cycling, kayaking, and beachcombing year-round (Life in Vancouver, 2024).

Vancouver is emerging as a hub for technology and innovation, particularly in industries such as software development, biotechnology, and clean technology; at the same time, the city is thriving in a startup ecosystem, world-class research institutions, and access to venture capital contributes to its reputation as a center for innovation (Technology, 2024).

Social and Cultural Issues

Vancouver has one of the most expensive housing markets in Canada, leading to issues of affordability and accessibility for many residents. Data shows that 53% of residents in Vancouver spend more than half of their household income on housing costs (Canadian Heritage, 2023). The high cost of housing has contributed to homelessness, particularly among marginalized communities, with many individuals living on the streets or in inadequate housing conditions (Canadian Heritage, 2023). From the newest report, in the city, there are more than 4,800 people are homeless in 11 communities (Canadian Heritage, 2023).

Vancouver has been grappling with a drug addiction crisis, particularly concerning opioid use (Isai, 2024). The city has experienced a significant number of overdose deaths, prompting calls for improved access to harm reduction services and addiction treatment that within 2023, 26 people died from drug use in Richmond (Isai, 2024). It also leads to the issue of mental health, including depression, anxiety, and post-traumatic stress disorder (City of Vancouver, 2024). CBC News said that Vancouver has ‘lower life satisfaction and worse mental health than others in B.C., and had a lower sense of belonging to their community’ (Kulkarni, 2024).

Culturally, since Vancouver comprises diverse religious, ethnic, and cultural groups representing various parts of the world alongside Canada’s Indigenous communities, cultural diversity and Indigenous is a challenge for the government to provide unrestricted access to civic services and live without prejudice or discrimination (City of Vancouver, 2024).

Environmental Issues

Vancouver is susceptible to the impacts of climate change, including rising temperatures, changes in precipitation patterns, and more frequent extreme weather events. Poor air quality, primarily due to vehicle emissions, wildfire, industrial activities, and residential heating, is one of the biggest concerns in Vancouver, especially during periods of high traffic congestion and stagnant atmospheric conditions (The Columbian, 2024). Four Vancouver facilities emitted 782,861 metric tons in 2021, and just one natural gas-powered facility, River Road Generating Plant, alone produced 737,163 metric tons of greenhouse gases (The Columbian, 2024).

Urbanization and development in Vancouver are other big concerns that lead to habitat loss, fragmentation, and degradation, threatening biodiversity and ecosystems (The Nature Trust of British Columbia, 2024). Loss of natural areas, wetlands, and green spaces can also diminish the city’s resilience to climate change and reduce opportunities for outdoor recreation and wildlife habitat (The Nature Trust of British Columbia, 2024).

While the government has already put efforts to promote waste reduction and recycling, with the closure of landfills and limited capacity for waste processing, Vancouver still faces challenges related to waste generation, disposal, and recycling (C. B. C. News, 2023). Single-use items are a challenge to the customers’ habit that ‘in 2018, the City of Vancouver estimated that 82 million coffee cups go into the landfill’ (C. B. C. News, 2023).

Sustainability Plan

The Greenest City 2020 Action Plan (GCAP) outlines Vancouver's ambitious goal to become the greenest city in the world by 2020. The plan, approved by the City Council in 2011, encompasses ten goal areas and 15 measurable targets to guide the city toward sustainability (Greenest City, 2020).

As highlighted in the preceding section, Vancouver grapples with challenges such as air pollution, vehicle emissions, and wastewater management, has all been addressed in its sustainability plan through specific targets and solutions (Greenest City, 2020). Given the issue of air pollution, the government will take initiatives such as investigating programs like gas pump labeling and collaborating with Metro Vancouver to ensure air quality monitoring and analysis (Greenest City, 2020).

In response to concerns about vehicle emissions, the city plans to enhance walking and cycling infrastructure, extend the Millennium Line SkyTrain, introduce new B-Line routes, expand bus services, and station upgrades (Greenest City, 2020). Additionally, the plan targets a 33% reduction in per capita water consumption from 2006 levels, with a range of comprehensive actions outlined to address wastewater management effectively (Greenest City, 2020).

Besides, the implementation of initiatives such as food scrap collection programs, the expansion of farmers’ markets and community gardens, and the creation of green jobs are also key target achievements for the plan (Greenest City, 2020). Vancouver's government wants to build a vibrant and resilient city that balances development and nature.

The plan involves collaboration with residents, businesses, and communities, with input from over 46,000 individuals and refinement based on feedback from over 850 community members (Greenest City, 2020). Over 50 new actions have been identified to further progress toward the 2020 targets and solidify Vancouver's position as a global leader in sustainability (Greenest City, 2020).

The city of Vancouver also has committed to extending sustainability beyond 2020, with the city joining the Carbon Neutral Cities Alliance to cut greenhouse gas emissions by at least 80% by 2050 and transition to 100% renewable energy by the same year (Greenest City, 2020). The GCAP is structured around three aspirational goals: zero carbon, zero waste, and healthy ecosystems, with actions prioritized based on their contribution to multiple targets (Greenest City, 2020).

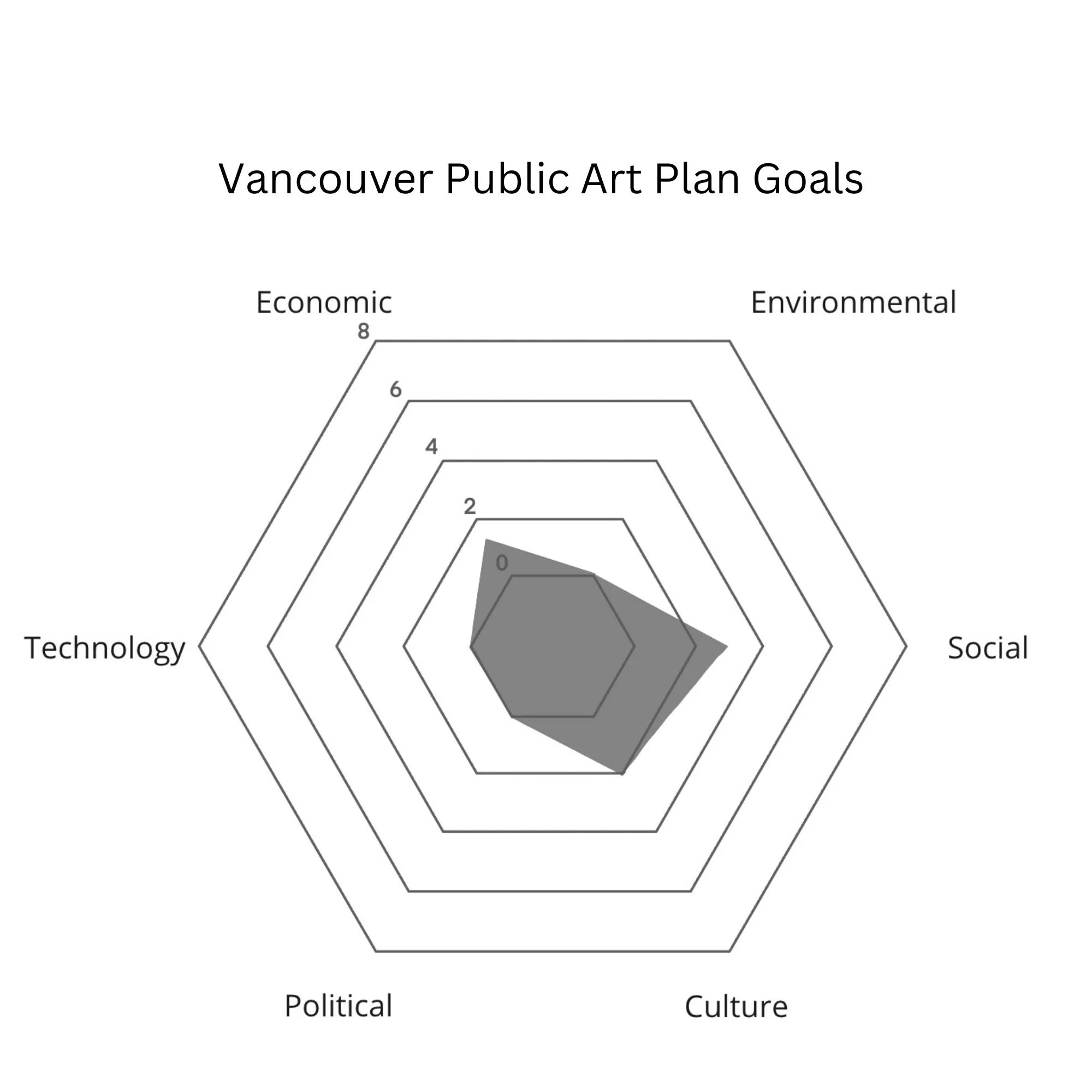

Chart created by author.

Public Art Plan

Vancouver is a city that has a diverse cultural ecosystem featuring various artists, cultural organizations, and venues, and it has a comprehensive 18-page public art plan for 2020 (Vancouver Public Art Plan, 2020). The plan highlights the public art collection build-up and maintenance that consists of artwork acquired through donations, commissions, or purchases under the authority of the City Council (Vancouver Public Art Plan, 2020).

One of the other main portions of the plan mentioned the scope, requirement community input, acquisition types, and placement of works of art for public art, as well as the maintenance plan (Vancouver Public Art Plan, 2020). Criteria for inclusion in the collection include preference for local or regional artists, strength of concept, originality, aesthetic quality, appeal to a broad audience, suitable condition, durability, safety, site availability, and maintenance requirements (Vancouver Public Art Plan, 2020).

The public art plan mentioned the seven purposes of the plan. As stated in the plan, ‘providing a legacy of art and culture for future generations,’ one of the purposes of the plan is to outline objectives to steward Vancouver’s heritage assets and contribute to the cultural identity through arts and public events (Vancouver Public Art Plan, 2020).

The public art plan also aims to integrate artwork into public spaces with easy access to the public and reflect the city’s diversity and character through various artistic viewpoints and mediums. (Vancouver Public Art Plan, 2020). The purpose of the plan is to enhance Vancouver's cultural landscape, promote both local and international artists, enrich public spaces, contribute to the city's identity and vibrancy, and foster international communication worldwide (Vancouver Public Art Plan, 2020).

Stimulate local economics is also considered in the plans, which say to ‘consider economic development and cultural tourism when advocating for public art,’ since public art plays a significant role in promoting cultural tourism by showcasing a city’s unique identity, history, and artistic talent (Vancouver Public Art Plan, 2020).

Chart created by author.

Analysis

The sustainable plan primarily focuses on environmental sustainability, focusing on issues such as climate change, air pollution, vehicle emissions, and waste management. Also, there is a goal to develop the local economy; it emphasizes establishing a green economic system that promotes jobs related to environmental sustainability. The plan also highlighted the threat brought by climate change, stating that ‘Climate change is one of the greatest threats in human history to human health, the economy, and the environment.’

In contrast, the public art plan is more practical. Rather than emphasizing specific targets, it briefly outlines seven essential purposes and is more like a handbook for the submission of artists and professionals, detailing the types of public art the city seeks. In addition, the plan explores the role of tourism in improving the economy, offering an interesting perspective from the government. Furthermore, by fostering artist diversity and providing more opportunities for artists, the city is looking forward to fostering cultural identity and heritage, along with some social concerns that can be addressed through the power of public art.

Both the sustainable and art plans of the City of Vancouver address similar targets related to cultural, economic, and social issues that align with the city's current challenges. However, while the sustainable plan primarily focuses on environmental sustainability, this aspect is lacking in the art plan. However, the public art section only concentrates on social diversity.

Nonetheless, public art has the potential to mitigate environmental challenges significantly. Establishing environmental public art can raise awareness among the public about the importance of addressing climate change and other environmental issues. Additionally, environmental public art forms such as land art, biophilic art, and ecological art, which utilize sustainable materials, can help reduce resource waste and air pollution.

Furthermore, public art can also help address other social problems faced by Vancouver, such as mental health issues. The presence of public art in the city can contribute to the cleanliness and aesthetics of urban spaces, potentially improving the mental well-being of residents. Simply experiencing the beauty of public art can raise the spirits of daily residents. Moreover, there are specific types of public art designed with the purpose of facilitating psychological healing. By incorporating those aspects and purposes more explicitly into the public art plan, it can further enhance its impact.

Brussels, Belgium

Brussels is situated in the central part of Belgium, and there are 19 municipalities in the Brussels Capital Region (Brussels Geography, 2024). Geographically, it lies within the Brussels-Capital Region, which is surrounded by the province of Flemish Brabant (Brussels Geography, 2024).

In terms of climate, Brussels experiences a temperate maritime climate influenced by the North Sea experiencing an oceanic climate (Brussels Geography, 2024). This results in mild winters with temperatures averaging around 1-5°C (34-41°F) in January and relatively cool summers with temperatures averaging around 14-23°C (57-73°F) in July (Brussels Geography, 2024). Rainfall is evenly distributed throughout the year, with no distinct dry season, and snowfall is infrequent in the city (Brussels Geography, 2024).

Image: Brussels Geography - Climate, Location, Population

Image Source: Brussels.com

Social and Cultural Background

Brussels, with its expansive municipality and historic center, is the largest city within the Brussels-Capital Region, home to roughly 1.2 million residents. The social landscape of Brussels has a rich diversity of cultures, languages, and traditions, reflecting its status as the capital of Belgium and the European Union (Belgium: the heart of Europe, 2024).

Established between the 8th and 10th centuries, Brussels gradually ascended as a prominent trading hub, and later, throughout its storied past, it has been governed by various entities, including the Spanish, Austrian, French, and Dutch (WCCF Editor, 2024). Thus, Brussels is composed of regions and linguistic communities speaking Dutch, French, and German. At the same time, Brussels takes pride in its identity as more than merely a cultural center; it views itself as a mosaic of cultures (WCCF Editor, 2024).

Social and Cultural Issues

Brussels is home to a diverse population, including many immigrants and refugees. ‘Brussels had 45 different nationalities with at least 1000 inhabitants’ (WCCF Editor, 2024). Thus, integration into society can be challenging, and it leads to social tensions and disparities in access to employment, education, and social services (European Education Area, 2024). For historical reasons, Brussels is officially bilingual (French and Dutch), but linguistic divisions still persist, impacting political representation, public services, and social cohesion (WCCF Editor, 2024).

At the same time, Brussels is experiencing social issues of poverty and social exclusion, with disparities in income, education, and housing outcomes among different communities (The Brussels Times, 2024). From the newest 2023 report, 2,150,000 people, which is 18.6% of the total population, are exposed to the risk of poverty or social exclusion (The Brussels Times, 2024).

One another significant issue faced by Brussels is traffic congestion which the city has been named the 14th worst traffic in the world and the 7th worst in Europe (Flanders News Service, 2023). During peak hours, the city’s road network experiences heavy traffic congestion that will lead to delays, pollution, and commuters’ health problems (Flanders News Service, 2023).

Environmental Issues

Brussels is vulnerable to the impacts of climate change, especially more frequent heatwaves, heavy rainfall, and flooding, which pose risks to infrastructure, public health, and the environment (Belgium, 2023). Due to traffic congestion and industrial emissions, Brussels suffers from poor air quality, with a period of ‘moderate’ air quality in early 2021, which will directly cause diseases like cancer or cardiovascular disease (Brussels Air Quality Index, 2024). Besides, according to the European Environment Agency, other most significant sources of air pollution in EU countries are household heating, energy production, industry and agriculture (Brussels Air Quality Index, 2024).

Moreover, Brussels faces challenges related to urban sprawl and the loss of green spaces. The city stands as one of the most densely urbanized areas in Europe (Demographia, 2004). Since the 1960s, it has witnessed urban sprawl, leading to the creation of fragmented landscapes within the region (Poelmans & Rompaey, 2009). Data show that the urbanized area of Brussels spans around 50 square miles and is inhabited by approximately 950,000 people, resulting in a density of nearly 19,000 individuals per square mile (Demographia, 2004).

Sustainability Plan

The Municipal Plan for Sustainable Development, also known as BXL 2050, is a comprehensive sustainable urban development strategy aimed at guiding the growth and development of Brussels until the year 2050 (Municipal Plan, 2016). It is designed to address various challenges faced by the city while promoting sustainability, inclusivity, and resilience (Municipal Plan, 2016).

One of the central goals is to transition Brussels into a carbon-neutral city, reducing its carbon footprint and mitigating the effects of climate change (Municipal Plan, 2016). This involves implementing measures to improve energy efficiency, promote renewable energy sources, and reduce greenhouse gas emissions across various sectors (Municipal Plan, 2016).

The plan also emphasizes the importance of social equity and inclusivity, seeking to address equal access to common goods and quality public services like transportation, poverty, and housing (Municipal Plan, 2016). Thus, it embodies the concept of a ‘10-minute city’, which aims to provide every inhabitant of Brussels with 10 minutes of amenities necessary for urban life (Municipal Plan, 2016). The government also hopes to bring diversity in economic and cultural aspects, such as origin, age, disability, gender, and sexuality, to make Brussels an ‘open and inclusive city’ (Municipal Plan, 2016).

As the national and European capital, the sustainability plan emphasized Brussels’ commitment to sustainably becoming an exemplary and participatory city (Municipal Plan, 2016). It aims to take proactive responsibility in driving change and setting a positive example for other cities (Municipal Plan, 2016). Moreover, the government is also seeking the opportunity to directly participate in the management and development of the surrounding environment and communities, fostering a collaborative approach to sustainable development (Municipal Plan, 2016).

The plan also has a more detailed plan for the seven major territories of the city, including the Pentagon, the North Quarter, the European Quarter, Laeken, Neder-Over-Heembeek, Haren, and the Louise Quarter, which emphasizes spatialization (Municipal Plan, 2016). The government is trying to achieve the plan’s overarching objectives and sustainable development at the scale of each quarter (Municipal Plan, 2016).

Chart created by author.

Public Art Plan

The city of Brussels puts a lot of effort into public art and urban development, but there isn’t a single comprehensive public art plan specifically named for the city. From visit.brussels street art is highlighted the street art in Brussels that brings beautification to the city (Street Art in Brussels, 2024).

From the press, it shows that the goal of urban art in Brussels is to foster a vibrant and diverse street art scene while promoting tolerance, creativity, and freedom of expression (Carey, 2024). It is said that The Urban Art Committee is responsible for acquiring new public art pieces and maintaining existing works, ensuring that street art integrates seamlessly into the urban environment and contributes to the city’s aesthetic appeal (Carey, 2024).

Also, the goal of public art is to provide cultural experiences for residents and visitors. The city offers themed trails for visitors to explore street art locations throughout the city, enhancing cultural tourism and showcasing the diverse forms of urban art present in Brussels (Carey, 2024).

Officially, the government of Brussels has established a ‘Call to Walls’ program that invites private property owners to offer their buildings as canvases for artworks, promoting freedom of expression and creativity in public spaces (Carey, 2024).

Chart created by author.

Analysis

The sustainable plan for the city of Brussels covers comprehensive aspects, including economic, social, cultural, environmental, and even political considerations, given its unique political background. However, these points are not adequately reflected in the realm of public art. Currently, even though Brussels has a thriving art atmosphere, the government lacks a specific public art plan or comprehensive art strategy. Only the press shows that recent developments in public art in Brussels indicate that the public art sector is increasingly addressing social and cultural issues within the city.

The city of Brussels faces problems like linguistic tension, air pollution, cultural diversity, and lack of access to employment or education, and the presence of public art can mitigate that problem. As the city is linguistically Dutch and French, they even have a culture center and a culture center on their city website. The presence of public art can serve as a platform for fostering understanding and dialogue between linguistic communities.

Public art installations can raise awareness about environmental issues, and green art installations, such as vertical gardens and eco-friendly sculptures, can directly contribute to urban greening efforts and improve air quality.

Moreover, public art can promote cultural understanding and appreciation by celebrating the diverse cultural heritage of Brussels’ communities. Artistic representations of different cultural traditions and histories can foster a sense of belonging and pride among residents. At the same time, collaborative art projects involving community members from various cultural backgrounds can promote social cohesion and unity.

In addition, public art programs that engage local communities, including youth and marginalized groups, can provide valuable skills training and employment opportunities. Art-based education workshops can empower individuals with creative skills and pathways to economic independence. Moreover, using public art to foster local economic extends beyond cultural enrichment. It also has the potential to stimulate local economic growth, not only limited to the art industry.

Comparative Analysis

From unique geographic and climate situations, Singapore, Brussels, and Vancouver are facing different challenges. Environmentally, Singapore faces challenges such as air and water pollution, water scarcity, and vulnerability to climate change impacts like rising sea levels and extreme weather events, while Brussels faces issues including air pollution, traffic congestion, and urban sprawl, and Vancouver grapples with air pollution from vehicle emissions, waste management challenges, and habitat loss from urban development.

When facing social challenges, Singapore had comparatively more serious income inequality, housing affordability, an aging population, and issues related to migrant workers’ rights and integration. Brussels had cultural diversity and integration, linguistic tensions, and disparities in access to education and employment opportunities, and Vancouver had homelessness, housing affordability, drug addiction, mental health issues, and disparities in income.

From the cultural aspect, Singapore’s cultural landscape is influenced by its multicultural society, which is related to racial harmony, social integration, and cultural preservation. Brussels is also a multicultural city but struggles with cultural identity, linguistic tensions, and integration. At the same time, Vancouver has struggled with the reconciliation with Indigenous peoples.

The Difference and Similarity in Solution

While facing different issues, each government has various resolutions to meet its goal of sustainability. In Singapore, the main focus of the sustainability plan is on the environment. Thus, the government has implemented policies and programs like investments in renewable energy and green technologies to address environmental challenges.

In Vancouver, sustainability plans are also centered around environmental concerns but with a broader focus on social and economic aspects as well. Thus, the government places policies like green transportation, reducing greenhouse gas emissions, and enhancing urban resilience to recover those challenges. Also, it is noticeable that the government places a strong emphasis on cultural enrichment and community engagement in its sustainability strategy.

Similarly but more comprehensively, the city of Brussels’ sustainability plan approach to economic, social, cultural, and environmental issues. Policies to promote urban greening, improve air quality, and foster social cohesion are mainly used. In addition, it is noticeable that Brussels’s sustainable strategy is influenced by the EU policy a lot since it is the capital of the EU.

Alignment Between Sustainability and Public Art Plan

Different scopes hinder the alignment between each city’s sustainability and public art plans and focus. In Singapore, the sustainability plan focused on technology and the environment, while the public art plan only acknowledged the importance of fostering cultural identity and heritage. There is limited alignment between the two plans, with public art initiatives not explicitly integrated into broader sustainability goals, especially for the technology part in which the sustainability plan places a lot of effort while the public art is not involved.

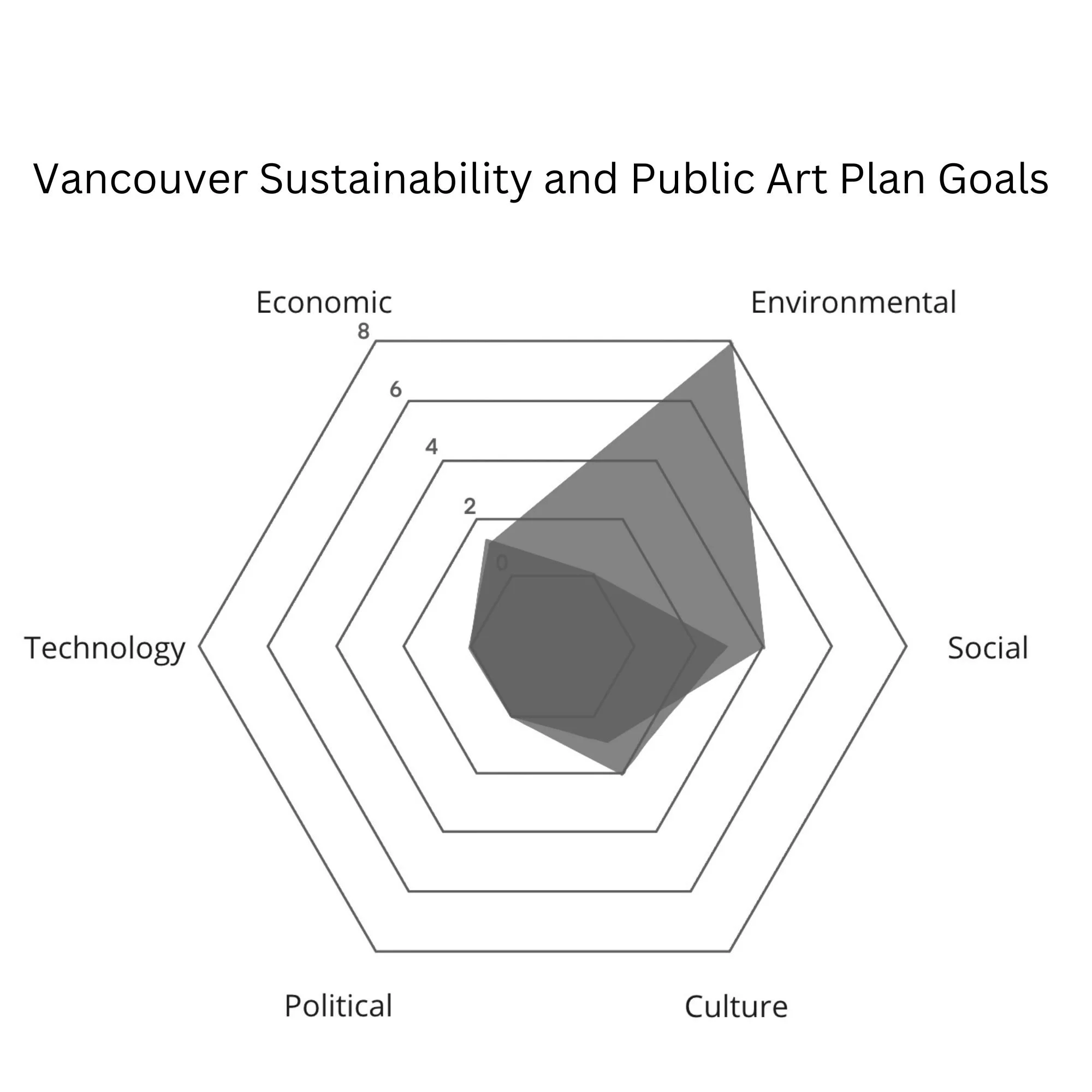

Chart created by author.

Similarly, in Vancouver, the sustainable plan emphasizes environmental sustainability but also addresses social and economic aspects. The public art plan, on the other hand, focuses more on cultural enrichment and community engagement. While there is some alignment in terms of promoting creativity and fostering social cohesion, public art plans are not fully integrated into the city's sustainability strategy.

Chart created by author.

In Brussels, sustainability efforts cover economic, social, cultural, and environmental dimensions, reflecting a comprehensive approach to urban development. Even though there is no specific public art plan, we do see public art contributing to cultural enrichment and social cohesion. From the diagram, there is some alignment between the goal of sustainability and public art plans in Brussels more than in Vancouver and Singapore.

Chart created by author.

The Potential of Public Art

Public art has the potential to help solve the major problems faced by Singapore, Vancouver, and Brussels. Among the general problems they are facing, public art can serve as a powerful platform for raising awareness about pressing issues such as environmental conservation, climate change, social inequalities, and cultural diversity. Artistic representations of the messages can engage the public in meaningful dialogues and educate communities about these important topics.

Public art projects that involve collaboration with local communities can foster social cohesion and unity. By providing opportunities for participation and expression, public art can empower individuals and promote a sense of belonging and inclusivity within diverse urban populations.

Moreover, by attracting tourists, fostering cultural tourism, and creating job opportunities, public art plans have the potential to stimulate local economic growth. Vibrant art scenes can also contribute help to the revitalization of urban neighborhoods that support small businesses and local artisans by attracting consumers.

In addition, public art can play an important role in preserving and celebrating the cultural identity and heritage of cities. Artistic representations of local traditions, histories, and landmarks can set a sense of connection among residents and contribute to the preservation of cultural heritage for future generations.

Public art possesses the potential to address many of the world’s current challenges. However, a significant disparity remains between its potential impact and the actual policy implementation in practice.

Conclusion

The goal of this research is to understand how public art can be utilized as a tool for achieving sustainability in the process of urban planning. The comparative analysis of Singapore’s, Vancouver’s, and Brussels’s sustainability and public art plans shows that while there is some alignment between the two, there remains a gap in fully integrating public art into cities’ sustainability strategies. The potential of the purpose of public art shows it can significantly influence urban economic, cultural, and environmental sustainability. Despite this potential, the current policy landscape fails to utilize the power of public art to mitigate pressing issues.

Moving to the future, realizing the critical role of public art in urban planning can help cities create more vibrant living environments through greater collaboration between government agencies, urban planners, artists, and communities.

-

“‘9. Art and Power’ in ‘Introduction to Art: Design, Context, and Meaning’ | OpenALG.” Accessed March 3, 2024. https://alg.manifoldapp.org/read/introduction-to-art-design-context-and-meaning/section/54129c96-ca5a-4108-832b-9e3180e85cc8.

“15 Influential Political Art Pieces | Widewalls.” Accessed February 17, 2024. https://www.widewalls.ch/magazine/political-art.

“About Singapore.” Accessed March 6, 2024. http://www.mfa.gov.sg/Overseas-Mission/Washington/About-Singapore.

“Amt Für Statistik Berlin Brandenburg - Statistiken,” March 8, 2021. https://web.archive.org/web/20210308125331/https://www.statistik-berlin-brandenburg.de/Statistiken/inhalt-statistiken.asp.

Art Scottsdale. “Art Scottsdale 21-22 Annual Report,” 2022.

Americans for the Arts. “Americans Speak out about the Arts an In-Depth Look at Perceptions and Attitudes about the Arts in America,” 2015.

“Acton’s New Public Art Project Showcases Businesses in Town - CBS Boston,” January 19, 2024. https://www.cbsnews.com/boston/news/acton-massachusetts-new-public-art-project-local-businesses/.

Ahammed, Faisal. “A Review of Water-Sensitive Urban Design Technologies and Practices for Sustainable Stormwater Management.” Sustainable Water Resources Management 3, no. 3 (September 1, 2017): 269–82. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40899-017-0093-8.

Amado, M P, C V Santos, E B Moura, and V G Silva. “Public Participation in Sustainable Urban Planning,” 2010.

Americans for the Arts. “Percent for Art Ordinances,” May 15, 2019. https://www.americansforthearts.org/by-program/reports-and-data/legislation-policy/naappd/percent-for-art-ordinances.

Americans for the Arts. “Why Public Art Matters: Green Paper,” May 15, 2019. https://www.americansforthearts.org/by-program/reports-and-data/legislation-policy/naappd/why-public-art-matters-green-paper.

“Arts and Culture | U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA).” Accessed March 2, 2024. https://www.bea.gov/data/special-topics/arts-and-culture.

Artterra. “What Is Sustainable Art?” Accessed February 11, 2024. https://artterra.ca/blogs/news/what-is-sustainable-art.

Ashley, Richard, Lian Lundy, Sarah Ward, Paul Shaffer, Louise Walker, Celeste Morgan, Adrian Saul, Tony Wong, and Sarah Moore. “Water-Sensitive Urban Design: Opportunities for the UK.” Proceedings of the Institution of Civil Engineers - Municipal Engineer 166, no. 2 (June 2013): 65–76. https://doi.org/10.1680/muen.12.00046.

Barrionuevo, Juan, Pascual Berrone, and Joan Ricart. “Smart Cities, Sustainable Progress: Opportunities for Urban Development.” IESE Insight, September 15, 2012, 50–57. https://doi.org/10.15581/002.ART-2152.

BATTERY PARK CITY AUTHORITY. “Public Art.” Accessed February 7, 2024. https://bpca.ny.gov/places/public-art/.

Bernstein, Arla G., and Carol A. Isaac. “Gentrification: The Role of Dialogue in Community Engagement and Social Cohesion.” Journal of Urban Affairs 45, no. 4 (April 21, 2023): 753–70. https://doi.org/10.1080/07352166.2021.1877550.

Betsy Damon. “Public Art Visions and Possibilities: Views from a Practicing Artist.” Accessed February 26, 2024. https://www.betsydamon.com/select-writings/art-in-the-public-realm.

“Belgium — English.” Accessed March 10, 2024. https://climate-adapt.eea.europa.eu/en/countries-regions/countries/belgium.

Belgium: the heart of Europe and a founding member of the European Union. “Belgium: The Heart of Europe and a Founding Member of the European Union.” Accessed March 11, 2024. https://belgian-presidency.consilium.europa.eu/en/presidency/belgium/.

“Brussels Air Quality Index (AQI) and Belgium Air Pollution | IQAir,” March 11, 2024. https://www.iqair.com/us/belgium/brussels-capital/brussels.

“Brussels Geography - Climate, Location, Population.” Accessed March 9, 2024. https://www.brussels.com/v/geography/.

Brussels-Capital Region. “Go4Brussels 2030: Strategic Multi-Year Plan.” Accessed March 29, 2024. https://be.brussels/en/about-region/values-budget-and-strategy/strategy-and-policy-priorities/go4brussels-2030-strategic-multi-year-plan.

Cabasin, Linda. “Creating Change: Mural Arts Philadelphia.” Side of Culture (blog), December 4, 2020. https://sideofculture.com/2020/12/mural-arts-philadelphia/.

Cantoni, Marta Pucciarelli, Lorenzo. “A Journey through Public Art in Douala: Framing the Identity of New Bell Neighbourhood.” In Murals and Tourism. Routledge, 2016.

Caradonna, Jeremy L. “Sustainability: A New Historiography.” In Routledge Handbook of the History of Sustainability. Routledge, 2017.

Cartiere, Cameron, and Shelly Willis. The Practice of Public Art. Routledge, 2008.

California, State of. “San Francisco Bay Area Region- California Climate Adaptation Strategy.” Accessed March 13, 2024. https://climateresilience.ca.gov/regions/sf-bay-area.html.

Carey, Ceire. “Why Brussels Is Redefining Urban Art as an Expression of Freedom and Inclusivity.” World Cities Culture Forum, March 22, 2024. https://worldcitiescultureforum.com/city-project/urban-and-public-art-in-brussels/.

Checa-Artasu, Martín M. “The Walls Speak: Mexican Popular Graphics as Heritage.” In Murals and Tourism. Routledge, 2016.

“Credo Reference - Urban Design History.” Accessed February 11, 2024. https://search.credoreference.com/articles/Qm9va0FydGljbGU6NjYwMzU=.

“City of Vancouver Public Art Plan,” February 2020.

“Climate of Singapore |.” Accessed March 5, 2024. http://www.weather.gov.sg/climate-climate-of-singapore/.

City of Vancouver, “Climate Change Adaptation Strategy,” accessed April 2, 2024, https://vancouver.ca/green-vancouver/climate-change-adaptation-strategy.aspx.

“Comparateur de Territoires − Unité Urbaine 2020 de Bordeaux (33701) | Insee.” Accessed March 27, 2024. https://www.insee.fr/fr/statistiques/1405599?geo=UU2020-33701.

“Cultural Diversity In Vancouver - Moovaz.” Accessed March 7, 2024. https://www.moovaz.com/blog/cultural-diversity-in-vancouver/.

Dalbo, George. “Memorializing the Holocaust: Public Art, Collective Memory, and Upstander Education,” January 27, 2023. https://psu.pb.unizin.org/holocaust3rs/chapter/why-is-there-a-holocaust-memorial-here/.

Demographia . “BRUSSELS: Surburban and Suburbanizing,” May 29, 2004.

Deboosere, Patrick, Thierry Eggerickx, Etienne Van Hecke, and Benjamin Wayens. “The Population of Brussels: A Demographic Overview.” Translated by Mike Bramley. Brussels Studies. La Revue Scientifique Pour Les Recherches Sur Bruxelles / Het Wetenschappelijk Tijdschrift Voor Onderzoek over Brussel / The Journal of Research on Brussels, January 12, 2009. https://doi.org/10.4000/brussels.891.

DeShazo, Jessica L., and Zachary Smith. Developing Civic Engagement in Urban Public Art Programs. Blue Ridge Summit, UNITED STATES: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Incorporated, 2015. http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/cm/detail.action?docID=4086060.

Duffy, Owen. “Anish Kapoor: The Formation of a Global Art.” Theses and Dissertations, April 25, 2013. https://doi.org/10.25772/2EEH-0Z95.

Dupere, Katie. “15 Public Art Projects That Boldly Advocate for Social Justice.” Mashable, September 24, 2016. https://mashable.com/article/public-art-social-good.

Editor, WCCF. “Brussels.” World Cities Culture Forum, February 19, 2024. https://worldcitiescultureforum.com/city/brussels/.

Energy5. “Smart Cities Advancing Energy Efficiency and Social Sustainability.” Accessed March 1, 2024. https://energy5.com/smart-cities-advancing-energy-efficiency-and-social-sustainability.

“English Topographies in Literature and Culture : Space, Place, and Identity.” Accessed February 3, 2024. https://web.p.ebscohost.com/ehost/ebookviewer/ebook/ZTAwMHhuYV9fMTkzOTg0M19fQU41?sid=42d77875-0211-4ac0-a5b8-ec6109226c1b@redis&vid=0&format=EB&rid=1.

Evans, Fred. Public Art and the Fragility of Democracy: An Essay in Political Aesthetics. Columbia University Press, 2019. https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.7312/evan18758.

Flash Art. “Public Art, Cultural Memory and Social Change |,” May 8, 2020. https://flash---art.com/2020/05/public-art-cultural-memory-and-social-change/.

Fleming, Ronald Lee. The Art of Placemaking: Interpreting Community through Public Art and Urban Design. London: Merrell, 2007.

Frost, Warwick, Jennifer H. Laing, and Kim M. Williams. “Exploring the Contribution of Public Art to the Tourist Experience in Istanbul, Ravenna and New York.” Journal of Heritage Tourism 10, no. 1 (January 2, 2015): 57–73. https://doi.org/10.1080/1743873X.2014.945458.

“Funding Sources for Public Art.” Accessed March 2, 2024. https://www.pps.org/article/artfunding.

Fernandez, Celia. “These Are the 10 Most Sustainable Travel Destinations in the World—None of Them Are in the U.S.” CNBC, February 4, 2024. https://www.cnbc.com/2024/02/04/most-sustainable-destinations-tripadvisor.html.

Gesler, Wil. “Therapeutic Landscapes.” In The International Encyclopedia of Anthropology, 1–9. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, 2018. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118924396.wbiea1422.

The Global Goals. “Goal 17: Partnerships for the Goals.” Accessed March 31, 2024. https://globalgoals.org/goals/17-partnerships-for-the-goals/.

Hannum, Kathryn L., and Mark A. Rhodes II. “Public Art as Public Pedagogy: Memorial Landscapes of the Cambodian Genocide.” Journal of Cultural Geography 35, no. 3 (September 2, 2018): 334–61. https://doi.org/10.1080/08873631.2018.1430935.

Hein, Hilde. “What Is Public Art?: Time, Place, and Meaning.” The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism 54, no. 1 (1996): 1–7. https://doi.org/10.2307/431675.

Hickman, Robin, Peter Hall, and David Banister. “Planning More for Sustainable Mobility.” Journal of Transport Geography 33 (December 1, 2013): 210–19. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2013.07.004.

Holtug, Nils. “Identity, Causality and Social Cohesion.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 43 (September 8, 2016): 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2016.1227697.

———. “Social Cohesion and Identity.” In The Politics of Social Cohesion: Immigration, Community, and Justice, edited by Nils Holtug, 0. Oxford University Press, 2021. https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780198797043.003.0003.

Gordon, Jessica. “The Case of Water Management in Singapore,” n.d.

Government of Canada, Statistics Canada. “Population and Dwelling Count Highlight Tables, 2016 Census,” February 8, 2017. https://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2016/dp-pd/hlt-fst/pd-pl/Table.cfm?Lang=Eng&T=302&SR=1&S=86&O=A&RPP=9999&PR=59&CMA=0#tPopDwell.

“Greenest City 2020 Action Plan.” City of Vancouver, n.d.

Heritage, Canadian. “Canadian Heritage,” March 6, 2023. https://www.canada.ca/en/canadian-heritage.html.

Hu, Rong. “Public Art Aesthetics and Psychological Healing.” HTS Teologiese Studies / Theological Studies 79 (July 18, 2023). https://doi.org/10.4102/hts.v79i1.8827.

“Impact Of Climate Change In Singapore.” Accessed March 6, 2024. https://www.nccs.gov.sg/singapores-climate-action/impact-of-climate-change-in-singapore/.

Irvine, Katherine N., Sara L. Warber, Patrick Devine-Wright, and Kevin J. Gaston. “Understanding Urban Green Space as a Health Resource: A Qualitative Comparison of Visit Motivation and Derived Effects among Park Users in Sheffield, UK.” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 10, no. 1 (January 2013): 417–42. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph10010417.

Isai, Vjosa. “Residents Oppose Expanding Drug Use Sites to Suburban Vancouver.” The New York Times, February 17, 2024, sec. World. https://www.nytimes.com/2024/02/17/world/canada/richmond-british-columbia-drugs.html.

Keogh, Diane U., Armando Apan, Shahbaz Mushtaq, David King, and Melanie Thomas. “Resilience, Vulnerability and Adaptive Capacity of an Inland Rural Town Prone to Flooding: A Climate Change Adaptation Case Study of Charleville, Queensland, Australia.” Natural Hazards 59, no. 2 (November 1, 2011): 699–723. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11069-011-9791-y.

Knight, Cher Krause. Public Art: Theory, Practice and Populism. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing, 2008.

Krueger, Rob, and Susan Buckingham. “Towards a ‘Consensual’ Urban Politics? Creative Planning, Urban Sustainability and Regional Development.” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 36, no. 3 (2012): 486–503. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2427.2011.01073.x.

Kudacity. “World Cities by Climate.” Accessed March 13, 2024. https://www.kudacity.com/cset/by_climate.

Kuhlman, Tom, and John Farrington. “What Is Sustainability?” Sustainability 2, no. 11 (November 2010): 3436–48. https://doi.org/10.3390/su2113436.

Laing, Warwick Frost, Jennifer. “Heritage Murals as Tourist Attractions in Ravenna, Moldavia and Istanbul: Artistic Treasures, Cultural Identities and Political Statements.” In Murals and Tourism. Routledge, 2016.

Lanzl, Christina. “A Sustainable Approach to Public Art Education.” Public Art Review 17, no. 2 (Spring/Summer ///Spring/Summer2006 2006): 42–44.

“Largest Cities by Population 2024.” Accessed March 13, 2024. https://worldpopulationreview.com/world-cities.

“Learn about Heat Stress |.” Accessed March 6, 2024. http://www.weather.gov.sg/learn-heat-stress/.

“Life in Vancouver, Canada | UCEAP.” Accessed March 7, 2024. https://uceap.universityofcalifornia.edu/study-abroad-in-canada/life-in-vancouver-canada?f%5B0%5D=city%3A82&f%5B1%5D=country%3A13.

Lehtinen, Sanna. “New Public Monuments: Urban Art and Everyday Aesthetic Experience.” Open Philosophy 2, no. 1 (January 1, 2019): 30–38. https://doi.org/10.1515/opphil-2019-0004.

Los Angeles County Arts Commision. “An Evaluation of Civic Art and Public Engagement in Four Communities in South Los Angeles County,” May 2008.

Lucchinelli, Valeria. “Creating Art for Social Change: How Art Can Inspire Activism - Art Sprouts,” March 24, 2023. https://artsproutsart.com/creating-art-for-social-change-how-art-can-inspire-activism/.

Maier, Stephan. “Smart Energy Systems for Smart City Districts: Case Study Reininghaus District.” Energy, Sustainability and Society 6, no. 1 (September 5, 2016): 23. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13705-016-0085-9.

Market Urbanism. “The Limits of the Singapore Housing Model,” August 5, 2020. https://marketurbanism.com/2020/08/05/the-limits-of-the-singapore-housing-model/.

Mastandrea, Stefano, Sabrina Fagioli, and Valeria Biasi. “Art and Psychological Well-Being: Linking the Brain to the Aesthetic Emotion.” Frontiers in Psychology 10 (2019). https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/psychology/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00739.

Merve, Elif, Arş Gör, and E. Eren. “THE SIGNIFICANCE OF PUBLIC SPACE ART IN LANDSCAPE ARCHITECTURE,” 2018. https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/THE-SIGNIFICANCE-OF-PUBLIC-SPACE-ART-IN-LANDSCAPE-Merve-G%C3%B6r/b0bba3f407825e93761bb3bfb64a52d5c5aad935.

“Ministry of Foreign Affairs Singapore - About Singapore.” Accessed March 27, 2024. https://www.mfa.gov.sg/Overseas-Mission/Washington/About-Singapore.

Ministry of Home Affairs. “Maintaining Racial and Religious Harmony.” Accessed March 6, 2024. https://www.mha.gov.sg/what-we-do/managing-security-threats/maintaining-racial-and-religious-harmony.

“Municipal Plan for Sustainable Development - BXL 2050,” October 24, 2016. https://www.brussels.be/bxl2050.

Monteiro, Renato, José C. Ferreira, and Paula Antunes. “Green Infrastructure Planning Principles: An Integrated Literature Review.” Land 9, no. 12 (December 2020): 525. https://doi.org/10.3390/land9120525.

Mozos-Blanco, Miguel Ángel, Elisa Pozo-Menéndez, Rosa Arce-Ruiz, and Neus Baucells-Aletà. “The Way to Sustainable Mobility. A Comparative Analysis of Sustainable Mobility Plans in Spain.” Transport Policy 72 (December 1, 2018): 45–54. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tranpol.2018.07.001.

National Museum of the American Latino. “Healing Uvalde.” Accessed February 18, 2024. https://latino.si.edu/exhibitions/healing-uvalde.

“Nature’s Metropolis.” Accessed March 2, 2024. https://wwnorton.com/books/Natures-Metropolis/.

National Arts Council. “Our SG Arts Plan (2023 - 2027).” Accessed March 26, 2024. http://www.nac.gov.sg/about-us/oursgartsplan.

News ·, Akshay Kulkarni · CBC. “Metro Vancouver residents report lower life satisfaction, sense of belonging than rest of B.C. | CBC News.” CBC, February 21, 2024. https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/british-columbia/metro-vancouver-mental-health-bc-1.7120747.

News ·, C. B. C. “Metro Vancouver Lagging behind Goal of Diverting 80% of Waste from Landfills | CBC News.” CBC, January 6, 2023. https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/british-columbia/metro-vancouver-lagging-behind-goal-of-diverting-80-of-waste-from-landfills-1.6705434.

Nelson, Donald R. “Adaptation and Resilience: Responding to a Changing Climate.” WIREs Climate Change 2, no. 1 (2011): 113–20. https://doi.org/10.1002/wcc.91.

Nummenmaa, Lauri, and Riitta Hari. “Bodily Feelings and Aesthetic Experience of Art.” Cognition and Emotion 37, no. 3 (April 3, 2023): 515–28. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699931.2023.2183180.

Ofspub: Office for Standards in Pubs. “From the Earth to Heaven: 7000 Oaks and the Legacy of Trees as Media,” May 5, 2017. https://ofspub.wordpress.com/2017/05/05/from-the-earth-to-heaven-7000-oaks-and-the-legacy-of-trees-as-media/.

“Our Targets.” Accessed March 4, 2024. https://www.greenplan.gov.sg/targets/.

“Overview.” Accessed March 5, 2024. https://www.nea.gov.sg/our-services/climate-change-energy-efficiency/climate-change/overview.

Palmer, Joni M. “The Politics of ‘the Public’: Public Art, Urban Regeneration and the Postindustrial City—the Case of Downtown Denver.” Ph.D., University of Colorado at Boulder. Accessed January 30, 2024. https://www.proquest.com/docview/1095131493/abstract/37A55C5EED4242FDPQ/5?sourcetype=Dissertations%20&%20Theses.

PBS NewsHour. “How an Indiana City’s Investment in Public Art Mirrors Its Overall Turnaround,” February 21, 2023. https://www.pbs.org/newshour/show/how-an-indiana-citys-investment-in-public-art-mirrors-its-overall-turnaround.

“Public Art Tip Sheet - Public Art Handbook.” Accessed March 2, 2024. https://www.crt.state.la.us/dataprojects/arts/PublicArtHandbook/appendix/APX_Guides_Tips.htm.

PWC. “The Power of Visual Communication,” April 2017.

Poelmans, Lien, and Anton Van Rompaey. “Detecting and Modelling Spatial Patterns of Urban Sprawl in the Flanders-Brussels Region (Belgium).” Landscape and Urban Planning 93 (October 1, 2009): 10–19. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2009.05.018.

“Regeneration of Cultural Quarters: Public Art for Place Image or Place Identity?” Journal of Urban Design 11, no. 2 (June 1, 2006): 243–62. https://doi.org/10.1080/13574800600644118.

“Refugee and Migrant Integration into Education and Training | European Education Area.” Accessed March 10, 2024. https://education.ec.europa.eu/focus-topics/improving-quality/inclusive-education/migrants-and-refugees.

Rose, Emma, and Amanda Bingley. “Migrating Art: A Research Design to Support Refugees’ Recovery from Trauma – a Pilot Study.” Design for Health 1, no. 2 (July 3, 2017): 152–69. https://doi.org/10.1080/24735132.2017.1386499.

Ruopp, Stephanie. “How Art Education Fosters Critical Thinking and Why It Matters.” Arts Academy in the Woods, January 28, 2019. https://www.artsacad.net/how-art-education-fosters-critical-thinking-and-why-it-matters/.

Seresinhe, Chanuki Illushka, Tobias Preis, and Helen Susannah Moat. “Quantifying the Link between Art and Property Prices in Urban Neighbourhoods.” Royal Society Open Science 3, no. 4 (April 2016): 160146. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsos.160146.

Service, Flanders News. “Traffic Jams: Brussels Named 14th Most Congested City in the World.” belganewsagency.eu, February 17, 2023. https://www.belganewsagency.eu/traffic-jams-brussels-named-14th-most-congested-city-in-the-world.

“Singapore.” In The World Factbook. Central Intelligence Agency, March 13, 2024. https://www.cia.gov/the-world-factbook/countries/singapore/.

“Singapore Green Plan 2030.” Accessed March 26, 2024. https://www.greenplan.gov.sg/.

Singapore, National Library Board. “Public Housing in Singapore.” Accessed March 6, 2024. https://www.nlb.gov.sg/main/article-detail?cmsuuid=755fcc44-f348-4488-963b-27616cb2773e.

“Street Art in Brussels.” Accessed March 29, 2024. https://www.visit.brussels/en/visitors/what-to-do/street-art-in-brussels.

“SUOMEN PINTA-ALA KUNNITTAIN 1.1.2018 FINLANDS AREAL KOMMUNVIS 1,” n.d. https://www.maanmittauslaitos.fi/sites/maanmittauslaitos.fi/files/attachments/2018/01/Suomen_pa_2018_kunta_maakunta.pdf.

Small Zachary. “‘There Should Be Greater Transparency’: Public Art Becomes a Political Battleground.” ARTnews.com (blog), August 4, 2020. https://www.artnews.com/art-news/news/public-art-commission-controversies-new-york-san-francisco-1202696028/.

“Socially Engaged Public Art in East Asia.” Accessed February 12, 2024. https://web.p.ebscohost.com/ehost/ebookviewer/ebook/ZTAwMHhuYV9fMzE0OTM1OF9fQU41?sid=45195354-e02e-40e7-80b6-5af8cdcbe41b@redis&vid=0&lpid=lp_119&format=EB.

Solow, Robert. “An Almost Practical Step toward Sustainability,” 1993.

Song, Xiaran. “An Immersive Interactive Installation as Positive Technology from an Artistic Practice Perspective,” 221–34. Atlantis Press, 2024. https://doi.org/10.2991/978-94-6463-378-8_15.

Tan, Eugene K.B. “Angst, Anxieties, and Anger in a Global City: Coping with and Rightsizing the Immigration Imperative in Singapore.” In Immigration in Singapore, edited by Norman Vasu, Yeap Su Yin, and Chan Wen Ling, 37–66. Amsterdam University Press, 2014. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctt130h8hr.5.

The Columbian. “Vancouver among 16 Communities Most Impacted by Air Pollution, According to New State Report,” March 4, 2024. https://www.columbian.com/news/2024/jan/02/vancouver-among-16-communities-most-impacted-by-air-pollution-according-to-new-state-report/.

Tavares, Paulo Filipe de Almeida Ferreira, and António Manuel de Oliveira Gomes Martins. “Energy Efficient Building Design Using Sensitivity Analysis—A Case Study.” Energy and Buildings 39, no. 1 (January 1, 2007): 23–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enbuild.2006.04.017.

The Art Story. “Public Art Movement Overview.” Accessed March 2, 2024. https://www.theartstory.org/movement/public-art/.

“The Tourism Industry in New York City | Office of the New York State Comptroller.” Accessed February 5, 2024. https://www.osc.ny.gov/reports/osdc/tourism-industry-new-york-city.

TheCollector. “5 Artists Famous for Environmental Public Art,” August 9, 2023. https://www.thecollector.com/famous-artists-environmental-public-art/.

The Nature Trust of British Columbia. “Threats to Biodiversity.” Accessed March 9, 2024. https://www.naturetrust.bc.ca/conserving-land/threats-to-biodiversity.

The Statistics Department. “Key Household Income Trends, 2023,” 2023.

Times, The Brussels. “Poverty in Brussels: One in Ten Suffers from Severe Housing Deprivation.” Accessed March 10, 2024. https://www.brusselstimes.com/915634/poverty-in-brussels-one-in-ten-suffers-from-severe-housing-deprivation.

Tjin, Thum Ping. “Explainer: Inequality in Singapore.” New Naratif, April 28, 2023. http://newnaratif.com/explainer-inequality-in-singapore/.

“Total Defence Resources.” Accessed March 6, 2024. https://www.sg101.gov.sg//resources/resource-packages/tdresources/.

“Urban Agriculture | USDA.” Accessed March 3, 2024. https://www.usda.gov/topics/urban.

“Urban Design for Sustainability: A Study on the Turkish City.” Accessed March 1, 2024. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504500409469808.

Utilities One. “Art in Public Spaces Celebrating Community Culture through Construction.” Accessed March 3, 2024. https://utilitiesone.com/art-in-public-spaces-celebrating-community-culture-through-construction.

Utilities One. “Designing for Severe Weather Events Resilient Structures in Civil Engineering.” Accessed March 1, 2024. https://utilitiesone.com/designing-for-severe-weather-events-resilient-structures-in-civil-engineering.

Utilities One. “Energy-Efficient Construction Green Building Certifications and Standards.” Accessed March 3, 2024. https://utilitiesone.com/energy-efficient-construction-green-building-certifications-and-standards.

Utilities One. “Sustainable Transportation Infrastructure Prioritizing Low-Income Communities.” Accessed March 1, 2024. https://utilitiesone.com/sustainable-transportation-infrastructure-prioritizing-low-income-communities.

Utilities One. “The Role of Public Art in Transforming Waterfront Spaces.” Accessed February 19, 2024. https://utilitiesone.com/the-role-of-public-art-in-transforming-waterfront-spaces.

“‘Unmet Social Needs in Singapore: Singapore’s Social Structures and Pol’ by Braema Mathi and Sharifah Mohamed.” Accessed March 6, 2024. https://ink.library.smu.edu.sg/lien_reports/1/.

Vancouver, City of. “Arts and Culture.” Accessed March 7, 2024. https://vancouver.ca/parks-recreation-culture/arts-and-culture.aspx.

———. “Geography.” Accessed March 7, 2024. https://vancouver.ca/news-calendar/geo.aspx.

———. “Mental Health and Addiction.” Accessed March 9, 2024. https://vancouver.ca/people-programs/mental-health-and-addiction.aspx.

———. “Multiculturalism.” Accessed March 9, 2024. https://vancouver.ca/people-programs/multiculturalism.aspx.

———. “Weather in Vancouver.” Accessed March 7, 2024. https://vancouver.ca/news-calendar/weather.aspx.

Vancouver Economic Commission. “Technology.” Accessed March 7, 2024. https://vancouvereconomic.com/technology-in-vancouver/.

Vernon, _People:Cornelius, and National Library Board Singapore. “Singapore River (Historical Overview).” Accessed March 6, 2024. https://www.nlb.gov.sg/main/article-detail?cmsuuid=011fc400-0632-453b-8520-12ada317e263.

Wan, Audrey. “As Singapore’s Aging Population Grows, Businesses Are Courting Older Consumers.” CNBC, October 31, 2023. https://www.cnbc.com/2023/10/30/as-singapores-aging-population-grows-businesses-court-older-spenders.html.

Welch, Dylan. “The Ten Most Sustainable Cities In The World.” Green.org, April 21, 2023. https://green.org/2023/04/21/the-ten-most-sustainable-cities-in-the-world/.

Wells, Christopher W. “Green Cities, the Search for Sustainability, and Urban Environmental History.” Journal of Urban History 40, no. 3 (May 1, 2014): 613–20. https://doi.org/10.1177/0096144213516085.

Wiryomartono, Bagoes. “Environmentally Friendly Urbanism.” In Livability and Sustainability of Urbanism: An Interdisciplinary Study on History and Theory of Urban Settlement, edited by Bagoes Wiryomartono, 125–54. Singapore: Springer, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-13-8972-6_6.

“World Population by Country 2024 (Live).” Accessed March 27, 2024. https://worldpopulationreview.com/.

WWF-Singapore. “WWF-Singapore | Climate Change.” Accessed March 6, 2024. https://www.wwf.sg/climate/.

———. “Lesson Learned from the Ancient Greek Polis.” In Livability and Sustainability of Urbanism: An Interdisciplinary Study on History and Theory of Urban Settlement, edited by Bagoes Wiryomartono, 55–80. Singapore: Springer, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-13-8972-6_3.

———. “Urban Planning and Development.” In Livability and Sustainability of Urbanism: An Interdisciplinary Study on History and Theory of Urban Settlement, edited by Bagoes Wiryomartono, 81–100. Singapore: Springer, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-13-8972-6_4.

Wong, T. H. F. “An Overview of Water Sensitive Urban Design Practices in Australia.” Water Practice and Technology 1, no. 1 (March 1, 2006): wpt2006018. https://doi.org/10.2166/wpt.2006.018.

Zebracki, Martin. “Beyond Public Artopia: Public Art as Perceived by Its Publics.” GeoJournal 78, no. 2 (April 1, 2013): 303–17. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10708-011-9440-8.

Zarroli, Jim. “How Singapore Became One Of The Richest Places On Earth.” NPR, March 29, 2015, sec. Asia. https://www.npr.org/2015/03/29/395811510/how-singapore-became-one-of-the-richest-places-on-earth.

Ai, Weiwei. Untitled Refugee Life Jacket. 2017.

Beuys, Joseph . 7000 Eichen. 1982.

Denat de Guillebon, Jeanne-Claude , and Christo Vladimirov Javacheff. The Gates. 2005.

Fairey, Shepard. HOPE. 2008.

Gormley, Antony . The Angle of the North. 1998.

Kapoor, Anish . Cloud Gate. 2005.

Kobra, Eduardo . Ethnicities. 2016.

Peet, Yin. From Trash to Treasure. 2024.

Fazlalizadeh, Tatyana . Stop Telling Women to Smile. 2020.

Serra, Richard. Tilted Arc. 1981.

Vrubel, Dmitri. The Kiss. 1990.

Yamguen, Hervé. Les Mots Écrits de New Bell. 2008.