Written by Youssef Shokry

A trick of the light? A special dye that is reactive to photons? An illusion brought on by hallucination-inducing molecules in the air?

Well…all of that, and none of that too. This is The Hypersymbiont Dress, a work that is “stained with bacteria…[and] draws attention to ways in which our own bacterial flora could be enhanced to turn us into human superorganisms.” Artist Anna Dumitriu stained a dress with different species of bacteria that contain varying benefits to the ecosystem (both natural and human). Their interaction in a “closed system” such as the dress produces the pulsating effect shown in the video below.

Figure 1: Video showing The Hypersymbiont Dress in motion. Source: Anna Dumitriu on Vimeo.

The dress was exhibited at contemporary art museums around the world, and critics and publications treated it as a “serious” piece of art, something worthy of critical analysis. Digital arts and culture site Neural described the decision to use a dress as a staging for the bacteria as significant, saying:

…[i]t is in fact a very strong representation of …[what] distinguishes us from animals…The dress, which is so finely embroidered and elegantly enlightened by the ever-changing trails; lit, like a living microcosm.

Anna Dumitriu is the “artist” in that she produced a piece of the creative work, but I would argue she worked in collaboration with the microorganisms whose molecular activity created the shimmering patterns on the dress. Can we consider the bacteria “artists” as well? More to the point, can we hold them to the same artistic scrutiny that we hold Dumitriu? What was their “intentionality” when responding to stimuli designed to produce the effect in the above video? Does art require “intentionality,” and if so, could a painting, musical composition, sculpture, or other creative endeavor be considered art if made by a non-human entity?

More to the point, could it be “good” art? Would it get a glowing write-up in the New York Times or purchased at auction for millions of dollars? If a piece produced via machine learning was placed next to something painted by a human, could we tell the difference? Does the work tell us something about the algorithm that made it, or the programmer/artist who wrote the algorithm?

Critiquing AI-generated art

Publications such as VICE have enlisted critics to offer up tongue-in-cheek critiques of artworks by generative adversarial networks (GANs), AI systems that artists and researchers use to create art via data scraping and comparing them to a base set of data. One part of the network tries to replicate the data, while the second part attempts to distinguish between this output and the real thing.

Art critic Jerry Saltz interrogates the “humanity and originality” of each piece of GAN-produced work, pointing out how unoriginal or dull or uninspired they are. One can’t escape the thought that he resents these attempts at artwork, the results of bloated programmer ego and amateurism.

Figure 2: Video of art critic Jerry Saltz critiquing AI-generated art. Source: VICE News on YouTube.

There is one moment, however, where he derides the programmers “for not freeing the program,” implying that the blame for these pieces being so dull and unoriginal lies with the humans writing the code. A machine learning system, an artificial intelligence, is only as powerful or creative as its human co-pilot. If the dataset and instructions a GAN or other AI receives don’t allow for a wider range of creative liberties, the result will be works like the ones in the VICE video above.

Another art critic, Mike Pepi, lambastes, “tech people coming in and willy-nilly trying to use these interesting GAN networks to spit out something that just sort of looks [emphasis added] surrealist or abstract.” AI should be more than a novelty, these critics argue. Creators should add some dimension to the work, making it more than just about the novelty of a machine producing a work of “art.” There needs to be intentionality behind the work, meaning the human writing the algorithm needs to imbue their creation with some “spark” that could feasibly generate something new, something vibrant, something worthy of praise.

Pepi also draws attention to a component of the AI/art intersection that we shouldn’t ignore: capitalism and the seemingly eternal march toward automation. “If machine intelligence can conquer this uniquely human realm [creativity], the march to artificial general intelligence must be nigh, and the profits unimaginable,” he writes. Developers at Google’s Artists and Machine Intelligence group offer a more optimistic, future-forward defense of their project: AI, like every other leap forward in art practice across centuries, will be embraced by some, shunned and leered at by others, but it is what’s coming. The head of the group, Blaise Aguera y Arcas, doesn’t ever explicitly say that there is an economic element to their research, but knowing Google, it’s not difficult to imagine the future profits they can reap from investing time and resources into this very specific part of AI research.

For some, profits are already coming in whether the work is considered “art” or not. In 2018, a GAN-created piece of work, Edmond de Belamy, sold at auction at Christie’s for over $400,000. The GAN used over 14,000 portraits made between the 14th and 20th centuries to perform its learning/comparing task. Another GAN artist-human collaboration, Mario Klingemann’s Memories of Passersby I, pulls from a very similar dataset, but its algorithm produced never-before-seen faces and images into eternity. It sold at auction for $55,000, indicating at some level that there is a growing market for these kinds of works.

Figure 3: Faces from Memories of Passersby I by Mario Klingemann. Two elements of a GAN scrape data then compare it to what the other produced, until there is no match between the two. Haunting. Source: The Verge.

Creativity in AI

The possibility for AI-generated art is only slightly younger than the concept of artificial intelligence itself. If a core component of AI is the independent reproduction of human activity in machines, then “creativity” would not be impossible. In the 1960s, Bell Labs engineers tested the creative capacity of a large IBM computer, and the results “could have passed for a work in the print section at a museum of modern art,” as Mike Pepi writes in an article for the magazine Art in America. The room-sized computer couldn’t have “known” its instructions would generate an image perceived as worthy of placement in one of America’s fine art institutions. It knew that it had a task written into a command module by an engineer, and set out to run that task. Our interpretation made it a piece of art.

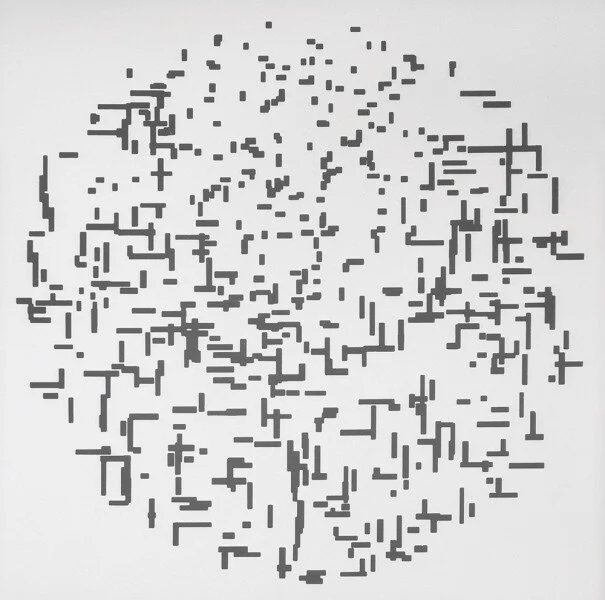

Figure 4: A. Michael Noll: Computer Composition with Lines, 1964. Good enough for the MoMA? Good enough for the refrigerator?

Art is subjective, to a very broad extent; as mentioned earlier, the creative capacity of a machine learning system, AI, or a GAN only goes as far as what the human on the other end writes into its code. The program doesn’t know what a human face is; it knows that there is a bundle of informational nodes containing data it can draw on to learn what a face looks like. It can learn faces and sonatas and existentialist tracts and pointillism, but only because human agents know what those things are. When did the capacity to pursue these creative endeavors emerge in our evolution? The jury is out on that question. Creativity is hard to pin down, and trying to find a “creative locus” in the brain is effectively moot. At the same time, we aren’t entirely sure where language comes from, or at least there are competing theories. At some level, does it matter?

To artists and researchers utilizing AI in their work, it matters quite a lot. Creativity is in itself a generative method. We can’t drum up an idea without the open system-style structure our brains operate on. Remember: if we can create a machine learning system that passes some artistic Turing Test (the thought experiment from computer science legend Alan Turing that interrogates whether a human actor could tell if they were speaking to a computer or another human) then the door opens for future economic reaping.

Another “test” of computers and machines side steps the issue of these systems’ ability to trick a human interlocutor: the Lovelace Test, named in honor of computer science pioneer Lady Ada Lovelace and a “more rigorous AI detector” than what Alan Turing conceived of in the 1950s. Jordan Pearson wrote in an article for the technology site Motherboard in 2014:

An artificial agent, designed by a human, passes the test only if it originates a “program” that it was not engineered to produce. The outputting of the new program...can’t be a hardware fluke, and it must be the result of processes the artificial agent can reproduce.

In short, to pass the Lovelace Test a computer has to create something original, all by itself.

The original paper outlining the test, “Creativity, the Turing Test, and the (Better) Lovelace Test,” is more technical in its description as written in 2001, describing a “...restrictive epistemic relation between an artificial agent A, its output o, and the human architect H of A – a relation which, roughly speaking, obtains when H cannot account for how A produced o.” Lady Lovelace did not think that a computer, of its own capacity, could produce something truly creative; like Mike Pepi and Jerry Saltz, she believed that its output was a function of the programmer’s input. A computer is only as “creative” as the human agent writing its code, and even then calling its output “creative” is highly dependent on whether it “come[s] up with something that is new, that is surprising, and that has value.”

As a benchmark for the artistic and creative capacities of AI, the Lovelace Test gets closer to the heart of the matter than the Turing Test; it should be noted, however, that the Lovelace Test and an “artistic Turing Test” are not the same thing.

Case in point: after Edmond de Bellamy sold at auction, in 2018, researcher Harsha Gangadharbatla took note and asked: “okay, so some collector paid a lot of money for something that, at some level, could not distinguish one color swatch from another without a human teaching it. Is it art, though? If we showed someone the piece, could they tell if a human or AI created it? If Jerry Saltz saw this work, but wasn’t informed of its non-human aspect, could he tell?”

His team set up a series of experiments where the AI-produced work would go up against a replicated work by human artists. There were subtle differences in painting style that were not distinguishable to the layperson. The result? One in five participants incorrectly guessed which work was human-made and which was AI-made. While correct attribution to a human artist was a little better than to the “machine” artist, overall the participants couldn’t tell when a piece was AI-made. One of the experiments in the study investigated the effect of knowing who made the piece, but it found that any attribution of talent or evaluation was more based on preconceived notions of AI art.

Figure 5: Humans are slightly better at telling when another human made a piece than when it was made by AI. The question arises: how does that impact what that human thinks of the piece? Source: From “The Role of AI Attribution Knowledge in the Evaluation of Artwork,” Harsha Gangadharbatla.

Can we say, then, that these works “passed” the Lovelace Test? They were, after all, convincing enough that human research subjects could not tell when a piece was made by an AI. Not necessarily, at least based on the parameters of the test that its originators set up. It seems to pass an “artistic Turing Test”, at least as defined in this article, but the AI did not create something new, surprising, or of value.

Granted, the study was not investigating this aspect of the works, so it might be unfair to judge its findings against the Lovelace Test’s parameters, but as a matter of determining an artificial system’s ability to produce “good art,” the Lovelace Test offers a set of criteria that goes beyond the comparatively straightforward question of “can this AI artist fool a human?”

Whether or not a work of art created by a non-human entity—other animals or AI or cyborgs or robots—is “good” will be in the eye of the beholder. Critics and philosophers and researchers will quibble about aesthetics and the nature of creativity and ideas, and those are all really fascinating and important questions to raise and explore. What will our relationship—as humans, creative beings, critics, and thinkers—be with art as this move toward intelligent systems enmeshes itself more and more into the creative and productive process of art? In the grand scheme of things, it might not be the most monumental of changes—Blaise Aguera y Arcas at Google pointed out that new technologies have played a role in art for millennia, and AI is just one more new tool—but I would also argue that AI playing more and more of a role in creation and production fundamentally blurs the line between human and non-human entities. At the very least, it opens up new creative outlets for artists.

Figure 6: Four paintings by AI artist Ai-Da. Source: The Express.

AI as artist

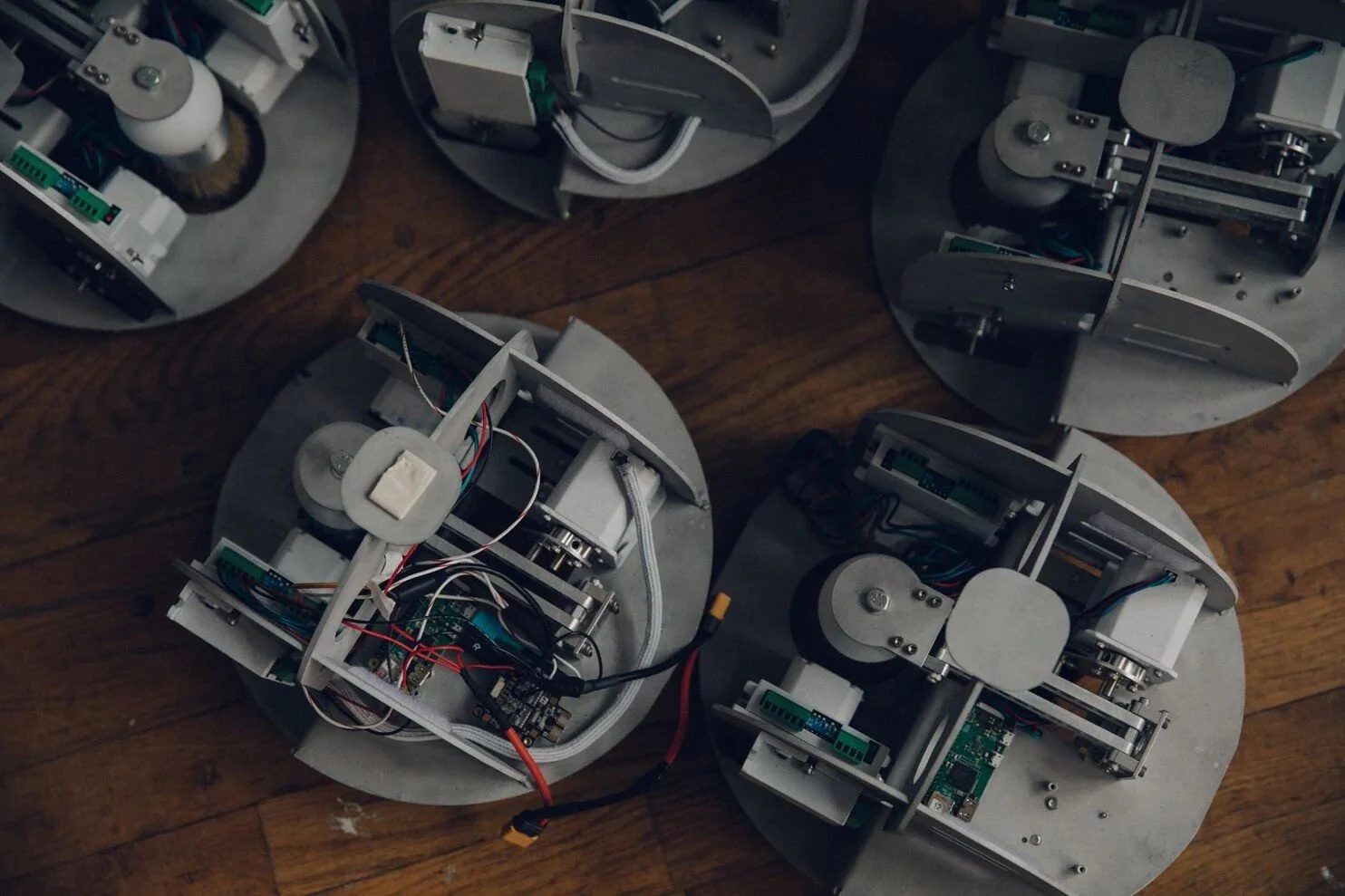

The four geometric images above are the work of Ai-Da, the first AI artist to have her own solo show of works. Created through a collaboration between art dealers and Oxford engineers, Ai-Da (her name is an homage to computer science pioneer Ada Lovelace) uses a neural network and facial recognition technology to analyze an image shown to her. She then processes and interprets the data that her neural network outputs, which guides her mechanical hand to draw or paint the image onto the canvas. This is not totally out of the realm of previous experiments into creating robotic artists: Sougwen Chen, a fellow artist/AI researcher out of the MIT Media Lab, created her own “AI collaborators” to paint and make art alongside her, and these robots are essentially fire alarm-sized units that can attach to a robot arm.

Ai-Da is very different, and by that I mean she is a simulacrum of a human artist: lifelike, capable of “independent” thought and, to some extent, “independent” creative capacity.

Figure 7: Photo of AI units created by Sougwen Chen. Source: Celeste Sloman for the Washington Post.

Figure 8: Ai-Da. Source: Nicky Johnston for TIME.

The uncanny valley-ness of Ai-Da is at once welcoming and familiar, yet distinctly eerie. In an article with British paper The Express, the project lead that brought her to the world, Adrian Meller, discusses how “it was absolutely paramount to make Ai-Da look as human as possible…[she] was developed as an ‘engagement piece’ for people to discuss and analyse the merits of AI technology.” In a way, Ai-Da is a “look” into the future, intentionally muddying the waters of creativity and technology; rather than an apocalypse scenario in which she and other AI-driven entities rise up and take over the planet, she is one look toward what human-machine interactions could be.

Conclusion

I started this piece discussing The Hypersymbiont Dress, a “collaborative” work between the artist and trillions of bacteria whose interactions and chemical processes produce the trance-inducing patterns that dance and pulsate across a white dress. These organisms responded to the stimuli Anna Dumitriu introduced into the system, but the biological reactions that they produced were wholly their own—the artist “set the stage,” so to say. The combination of the two actors, two subjects producing an object, gives rise to the work of art.

So is the case with human and AI. In “Coactivity: Between the Human and Nonhuman,” Artistic Director at MoCo Montpellier Nicolas Bourriaud describes contemporary art as “a gateway between the human and the nonhuman, a space where the binary opposition between subject and object dissolves and branches out in multiplicitous images.” The bridge from human to nonhuman in art, in interactions with the natural world, in external action outside of the self, creates objects imbued with subjective experience. An AI artist, a GAN, a neural network linked to a robot arm with a face and name—at some point in the narrative thread these are extensions of ourselves and become more than tools.

A piece of work created by an intelligent system could be considered an “amateur” in the strictest sense of the word as someone with no formal training, but we are not fully at the point in the journey of AI and machine learning where such a system could make something all its own. There is always a human input, at least for now, and the art critic is not only a mediator between mechanical artist and public—they are also assessing the creative spark in the programmer, or the human artist.

Can an AI ever be considered an artist? I think so. Would their art be “good”? I also think so, but my conception of “good” might differ from the critic, and at the moment the consensus there seems to be around a stodgy idea of “good.” Let’s just split the difference and say “sure.”

+ Resources

Aguera y Arcas, Blaise. “Art in the Age of Machine Intelligence.” Medium, February 23, 2016. https://medium.com/artists-and-machine-intelligence/what-is-ami-ccd936394a83.

Boucher, Brian. “Most People Can’t Tell the Difference Between Art Made by Humans and by AI, a Rather Concerning New Study Says.” Artnet News, April 27, 2021. https://news.artnet.com/art-world/machine-art-versus-human-art-study-1946514.

Bourriaud, Nicolas. “Coactivity: Between the Human and Nonhuman." Flash Art, 2019. https://flash---art.com/article/coactivity-between-the-human-and-nonhuman/.

Ciociola, Chiara. “Communicating Bacteria Dress, Bacterial Social Design.” Neural, March 21, 2012. http://neural.it/2012/03/communicating-bacteria-dress-bacterial-social-design/.

Dumitriu, Anna. "The Hypersymbiont Dress." Vimeo, 2017. https://vimeo.com/242357755.

Gangadharbatla, Harsha. “The Role of AI Attribution Knowledge in the Evaluation of Artwork.” Empirical Studies of the Arts, February 2021. https://doi.org/10.1177/0276237421994697.

Haynes, Suyin. “This Robot Artist Just Became the First to Stage a Solo Exhibition. What Does That Say About Creativity?” TIME, June 17, 2019. https://time.com/5607191/robot-artist-ai-da-artificial-intelligence-creativity/.

Kaufman, Sarah L. “Artist Sougwen Chung Wanted Collaborators. So She Designed and Built Her Own AI Robots.” The Washington Post, November 5, 2020. https://www.washingtonpost.com/business/2020/11/05/ai-artificial-intelligence-art-sougwen-chung/?arc404=true.

Kettley, Sebastian. “Artificial Intelligence BREAKTHROUGH: These Incredible Paintings Were Made by an AI ROBOT.” Express, June 7, 2019. https://www.express.co.uk/news/science/1137207/Artificial-intelligence-news-AI-robot-artist-paintings-robot-painter-AiDa.

Lim, Alvin. “AI Art House: Classical Paintings Birthed from Digital Minds.” The Peak, February 16, 2021. https://www.thepeakmagazine.com.sg/lifestyle/ai-art-house-classical-paintings-birthed-from-digital-minds/.

López de Mántaras, Ramón. “Artificial Intelligence and the Arts: Toward Computational Creativity." In The Next Step: Exponential Life, 99-123. Madrid: Turner, 2017.

Pepi, Mike. “Could There Ever Be an AI Artist?” Frieze, 2018. https://www.frieze.com/article/could-there-ever-be-ai-artist.

Pepi, Mike. “How Does a Human Critique Art Made by an AI?” Art in America, April 2020. https://www.artnews.com/art-in-america/features/creative-ai-art-criticism-1202686003/.

Stead, Chloe. “Is AI Art Any Good?” Art Basel, 2017. https://www.artbasel.com/news/artificial-intelligence-art-artist-boundary.

VICE News. "How Does A.I. Art Stack Up Against Human Art?" YouTube, 2018. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hws1ZTlkz_I.

Vincent, James. “A Never-Ending Stream of AI Art Goes up for Auction.” The Verge, March 5, 2019. https://www.theverge.com/2019/3/5/18251267/ai-art-gans-mario-klingemann-auction-sothebys-technology.