Robotics and textiles

In the latest installment of the Let’s Talk Podcast Interview series, AMT Lab staff member Natalie Larsen interviews a group of Carnegie Mellon University students & faculty who worked conjointly on a week-long “Jam"' at the Textiles Lab in order to create a fabric that produces sounds when stretched and manipulated.

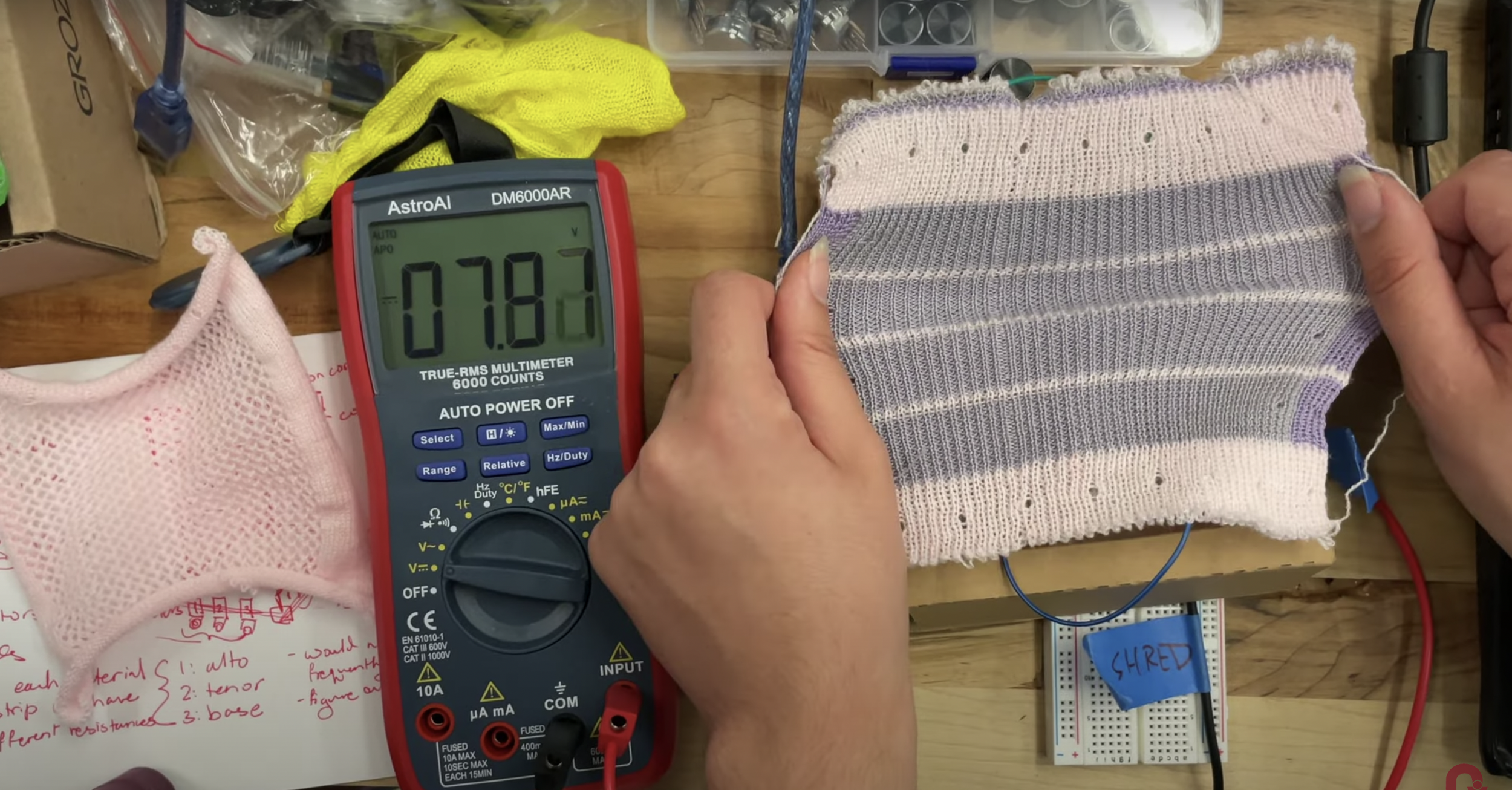

Image of Fabric + Sound Textiles Lab Jam via Youtube.

Fabric + Sound Textiles Lab Jam at CMU

Included on this panel are Robotics Institute Assistant Professor Jim McCann; Heather Kelley, Assistant Teaching Professor in the Entertainment Technology Center; and three students: Dee Iyer, Yuichi Hirose, and Miles Scharff. The researchers discuss how the creative process lends itself to technology, and how their project came together.

The Textiles Lab Jam was led by Carnegie Mellon University Robotics Institute Assistant Professor Jim McCann, and brought in students from the School of Computer Science’s Robotics Institute; the Entertainment Technology Center; the School of Music; and the Integrative Design, Arts and Technology Network (IDeATe).

Please note: This podcast was recorded over Zoom, so the audio quality may be a bit fuzzy at times.

Trailer: Jim McCann: But I, I will say that it seems like many of the great transformations in what we consider to be say fine art have been spurred on by the development of technology, uh, either in reaction to or adopt or via adoption of said technology. But if you want to get really fundamental, art is artifice, or art is anything that humans make. And technology is what humans use to make things. So there is no antagonism here at root.

Natalie Larsen: Welcome to another Let's Talk episode of Tech in the Arts, the podcast series on the Arts Management and Technology Laboratory. The goal of our Let's Talk series is to exchange ideas, bring awareness, and stay on top of the trends.

My name is Natalie Larson. I am the staff writer and lead researcher for AMT Lab and today I'm joined by Jim McCann, assistant professor in the Carnegie Mellon Robotics Institute, and some of the members of the Carnegie Mellon Textiles lab. This lab's goal is to extend the state of the art in textile design and fabrication, and they seek to foster collaboration. Over a week-long jam, this academically diverse group of Carnegie Mellon collaborators were able to produce and record sounds through manipulating textiles.

All right. Welcome, everyone. Thank you so much for joining us here today. To start, why don't we all just go around, say our names and just describe, what program you're coming from, and maybe briefly describe your role in the Textiles Lab?

Jim McCann: All right, so I am Jim McCann. I'm a professor in the Robotics Institute. Uh, the textiles lab encompasses a lot of my research. I run the lab, uh, set the agendas, et cetera.

Dee Iyer: Um, I'm Dee. I am a junior in electrical and computer engineering. My role in this project, um, I work with Yuichi and Miles on a textile, like foam roller that was intended to produce, uh, music through inductive purposes.

Heather Kelley: I'm Heather Kelley. I'm faculty over at the Entertainment Technology Center and I'm just a big fan of the Textiles Lab. And, uh, like to participate when there are things that I can jump into. And that started, uh, right before a pandemic with the, uh similar workshop we did, uh, about games, making games with what's available in the lab. And, uh, really had a great time doing that. And so when I heard and was talking to Jim about, uh, what could happen next the idea of music came up and uh, I'm a musician, so I was really interested in, in, uh, what could be made for that. So I managed to get myself over there, uh, for the week.

Yuichi Hirose: Hi, I'm Yuichi I'm, I'm a research assistant at the Textiles Lab, and usually I'm working on the development of soft knitting machine, so which, uh, the knitting machine which can be used like, uh, 3D printer. And I just like came to the U.S. and like July early July. And I attended this event, so it was really nice to, for me to make friends there. And I was working with Dee and Miles in this event.

Natalie Larsen: Great. Thank you so much. Um, so Jim, I'm gonna turn the first question over to you. Can you just briefly describe the beginnings of the textiles lab and maybe this whole project that you created?

Jim McCann: Sure. Uh, so. Let me start by saying the Textiles Lab itself is a research lab that's concerned with making new hardware and software tools to, uh, help everyone create textile artifacts, uh, in new and better ways. The lab really came out of work I started when I was at Disney Research and, uh, evolved over time. I joined Carnegie Mellon and brought, the lab with me. And we've done a lot of work on CAD tools for machine knitting, uh, ways of planning, stitches for quilting, just sort of interesting textile hardware and software stuff. And a tradition we've always had in the lab is to take a little bit of time every semester or every year, take a week out, and try to do some different things.

You know, stretch our brains a little bit, maybe acquire some new skills. Uh, try to look at things from a new direction and, this jam is one such of those excursions. I think the first Textiles Lab Jam we had was at Disney Research in 2014, and we've been on a pretty good schedule since then with one or two a year.

Natalie Larsen: Very cool. Thank you. So one thing when I was doing a little bit of research about the, the Textiles Jam was, um, one thing I found interesting about it was kind of the spirit of collaboration. You have people coming from different areas on campus, different backgrounds, faculty and students. I just thought that was really cool.

Um, can you, talk about, um, how different people from different backgrounds kind of contribute their skills and their knowledge to this, to these projects. Like say someone from an engineering background versus someone from a more creative like music background.

Jim McCann: Yeah.

One of the things that we try to do with the jams is make it so that, or use it as an opportunity to make new friends and connections and collaborations across campus. And uh, I think what's important about the structure is not that. For instance, we bring in Yuichi and say, okay, you, you are good at mechanical engineering, therefore you will do mechanical engineering.

You know, we're not trying to hire on employees or something. Instead we say, Hey, we're thinking of doing something in this topic area. What are you interested in doing? So we bring people in, not necessarily for the skills they have, but for the skills they want to use, uh, or the skills they want to acquire.

Um, I think that by having a, a relatively short commitment and having a relatively structured topic, it means that we can kind of, uh, network out and connect with the people who have those who have skills that they wanna acquire or use that are in line with the goal of the jam. And therefore we can build a good collaboration that way.

Natalie Larsen: Nice. That's awesome. Um, I'm gonna turn this over now to kind of anyone, um, who wants to kind of jump in on this question. Um, I'm just wondering more about the actual science of how you create the sounds with these like fabrics and, and just other materials.

Dee Iyer: Um, I can jump in here. Um, so kind of our main, um, Making, um, instruments or something similar out of fabric was to use, um, like electronics, um, in order to help us create a sound and kind of our saving grace. Um, in terms of need. Textiles we used, um, was this conductive yarn, um, that can be woven into different patterns to create different, um, resistances based on like how the, how many connections were present in the yarn. Um, especially for us. Um, we had, uh, collaborated with, um, someone who knew a lot about textiles and, um, she had created various [ patterns that provided us different, um, amounts of resistance, which changed, uh, respectively, the sound and we outputted through our circuit.

Jim McCann: Yeah. And I'll jump in to add that one of the things we did at the beginning of the jam was do some brainstorming about what possible ways we could get signals into and out of fabric that we could eventually use to manipulate sound. And we came up with ideas like, uh, how much light gets through the fabric or the resistance of the fabric or the electromagnetic radiation emitted by the fabric. That's the inductive sensing idea or vibration on the fabric. Uh, and I think we had a lot more on the board. Um, and sort of, uh, one of the fun things about this jam was doing that brainstorming, uh, and seeing this whole possibility space of which we really only explored a tiny piece with our projects.

And is there any like when you were doing this brainstorming, um, is there any plans in the future maybe to use the, the sounds that you made in other kinds of projects, like in maybe more collaborations with, um, like music recordings or anything like that?

Dee Iyer: Um, I would say like, I, I do a lot of like personal projects, uh, with electronic music, and I am considered using samples of what, um, like kind of my team created in terms of the fabric tape loop, but has not come to fruition yet, but maybe, maybe soon.

Heather Kelley: Yeah, I could say the same for me. I was very interested to develop some kind of, um, unique and sort of visually interesting controller for a, a synth that I already own and sort of just use the what we made as a way to control something that you would normally just, you know, flip a switch or turn a regular knob on the front of the synth, but could I make something that made it a little more performative and unusual? So that was, that was what I was working on, and I would say, yeah, the, the, prototype was successful, but it was also very small. So it wasn't something that I, you know, if I was going to go into performance, I probably would try to take it to another level.

Natalie Larsen: So again, anyone feel free to jump in, but What does the actual jam look like? Is it like a one, one-time thing, one event once a year, or is it kind of like ongoing?

Jim McCann: yeah, so, I think one of the important things about a jam is that you get a short period of strong commitment, but there is not any ongoing commitment. And so we run jams. A jam is a week long. People come in and they commit as much as they can to be there from ten to five, ten to six, working sort of full days with some flexibility cause people have other responsibilities. And then our commitment is that we brainstorm on Monday. We build Tuesday, Wednesday, Thursday, and we demo on Friday.

And uh, anything beyond that certainly happens, but, that's sort of bonus. So we're trying to really keep the time commitment short, but also intense without going into the craziness of staying up all night or any of that kind of hackathon flavor.

Natalie Larsen: Nice. I wanna kind of touch on this one idea that I read in an article about this, about this lab and it that's, um, that this project occurred when researchers craved a bit of an escape. Um, so what do you think this project achieves from like a creative or artistic perspective for researchers, staff, faculty, students who need that bit of an escape.

Dee Iyer: I guess I can kind of provide my perspective. In high school, I was part of a robotics team that had a very similar kind of vibe like when we would go to competitions, it was three days straight of, um, single-minded focus on one goal. And you kind of build, um, really good connections during a short amount of time. Cause you kind of get in a groove and everyone knows how everyone else works. So I think this kind of provided me, um, my first real similar experience to that since coming to college cuz group work is existent when it's limited, so this was a good opportunity.

Yuichi Hirose: I'd like to talk about my situations like this is just after I came to the U.S. and CMU. At that time I, had problems about like international shipping of my machine and I couldn't get my machine from Japan. And I, I was really worrying about it, but, um, and I did, like, I didn't know many people here yet. And this like jam was really helpful for me to like, um, not thinking about my machine for a while and then like shipment for a while and then like got know people in CMU. So it was, it was really helpful for me to do that. It was really nice to attend this jam.

Heather Kelley: I think for me it wasn't as much of an escape. Um, uh, but it was, um, I really love going into spaces where, uh, you know, the whole physical space is, built for creativity and, there were just so many components, like anything you needed was probably there or Jim would order it and it would be there very quickly.

And so it felt more like a playground. I really love that. There are, you know, there are a few other spaces like that on campus or in the city. But, yeah, just being able to walk into one that was kind of purpose-driven for that week around this specific need of making musical connections and making, you know, making the machines, uh, do interesting things. And of course having Jim's brain there in the room is also very helpful. So I had fun, but not for escape reasons, but more of like diving into the experience.

Jim McCann: Yeah, and I will build on that and say that a lot of the experience of being a professor is being very, uh, you'd say time sliced, you're doing all sorts of different things. And so I would say, as a professor, being able to focus on one thing for a week is in some ways sort of an escape from the time slicing.

Natalie Larsen: So again, kind of going back to that idea of collaboration, but just in, in a more like, Like a week-long period basically, where you're, you're working on this project. That's, that's really cool. So kind of going off of that, I'm curious about how the technology landed itself to the kind of creative approach.

Jim McCann: So I think in part we were, our major theme was working with textiles and sound production, but a minor theme was working with analog circuits and um, sort of simpler discrete components. And these are things that lend themselves to experimentation. You're sending them continuous voltage values and they're doing continuous things with them.

So they're always, they're always about sort of adjusting something a little bit and seeing [00:16:00] a, a little bit of a change or sometimes even a big change. Uh, whereas if we were doing this all in software, digital software on computers, you know, digital software is often either right or wrong. Whereas analog circuits, they're always sort of right and sort of wrong, and that's, I think, a little more fun for experimentation.

Dee Iyer: Yeah, I concur. I am a bit of an analog circuits enthusiast, I guess. Um, like for me personally, before this jam, I created a trautonium, which is kind of like a continuous, um, it's kind of like if you're playing a violin string and you can move your finger and it changes the pitch. And that was done with, uh, analog circuits as well. So I feel like coming into this, you know, that if you're generating sound electronically, it's probably gonna use those types of components.

Natalie Larsen: Awesome. So question kind of for the collaborators. Um, so Jim, I'll give you a little bit of a break. Uh, you all came into this from different backgrounds with different skills, as I mentioned before. What's something that you learned from the experience? And it can be anything. It can be technical, it can be interpersonal.

Yuichi Hirose: Yeah, I was kind of like new to these like analog circuits things. I was working with Dee and Miles also really good at these things and then so it was really nice to work with them. I could like learn a lot. I was also like busy like finishing the machine to do the rotating the fabric. So, but I just like working with them sit next to them and then like I was like saying that they're like very busy soldering. And they both act enthusiastically. So that [00:18:00] also like motivated myself to finish this machine, like before the deadline. So it was really fun.

Heather Kelley: I think one thing I appreciated and perhaps. Maybe, you know, you could say I learned it because it's more, um you get it more embodied if you, uh, just see it in a lot of different forms. Is that the connection between, uh, the aesthetic like the visual of the piece and the way it sounded and the way it actually worked technically was really interesting. Like there was one piece that was a drum, but it also looked like a really lovely, I don't know, pattern. It looked like it could be a piece of artwork hanging on, on, you know, in a gallery, but it was also a musical instrument. And, uh, another piece was more robotic. It was kind of a, a piece on a loop, um, but the different patterns of the, uh, yarn created, you know, slightly different variations in the sound. And just sort of like seeing more examples of how the sound was affected by the, the way that the piece was very like physically tangibly made, and then also how that kind of, you know, mixed the yarn is so colorful. Uh, people made different choices about how they wanted it to look. I just really appreciated seeing the, the variety of that.

Natalie Larsen: I wanna take a second here to introduce Miles who just joined us. Miles, if you wanna unmute yourself, just introduce yourself and maybe tell us a little bit about your background and your kind of role in the lab.

Miles Scharff: Hi, I'm Miles. I'm a recent grad from the CMU BSA program in physics and music tech. So I joined this experience from the music tech side. Um, I'm currently still at CMU doing some research in spatial audio. In this process I was, um, mostly focusing on the fabric tape loop project, which was super, super fun. Making, um, special microphones that pick up a lecture, magnetic waves that we're sending through the fabric and then able to listen to again. See if you get this lovely quality. Kind of like fabric distortion a little bit, which was super great.

Natalie Larsen: Nice. Thank you. I'm gonna open this up for anyone, uh, who wants to jump in.

Do you see any potential for any of the kind of technology that you work within any sort of artistic applications like museums or other types of experimental, artistic environments?

Miles Scharff: I personally do, um, especially the fabric tape loop project, mostly because it's kind of like a self-guided machine that it can just kind of go on forever, um, for as long as you want. And I, I, I did a little bit of work on it for like a day after, but I didn't wanna do too much because it would've, as, as Jim would say, it would ruin the spirit of the week-long collab and it would kind of become something else.

But I experimented a little bit with putting different sounds through it. Um, and I can imagine that there'd be a way to like, like generate new sounds over time. So, yeah, that's one way. And also with, um, with Heather's, um, beautiful, uh, fabric synth controller thing. I think like in a performance context, like the more physical you make your mode of operations, like, I think it can be interesting visually, but also like very interesting sonically.

Dee Iyer: Personally I, like Heather mentioned, um, that there was this drum that looked like an art piece, right? And I agree it was very aesthetically pleasing, um, and looked like it could belong pretty much in any like, decorative space. But the fact that it served, uh, dual purposes like that very much could be taken further and explored with like, immersive experiences in, um, some sort of museum. But, you know, I, I don't think I'm artistically minded enough to come up with that well that one be. But, uh, I certainly could see, uh, something for that.

Miles Scharff: I also feel like fabric as a medium, like visually and, um, textually or haptically is very approachable. Um, so I think like in a, in an artistic space or a museum space, it's kind of like a very unexpectedly easy window into experiencing these types of works.

Natalie Larsen: Yeah, it would be, I think, really cool to see something like that in like an immersive museum exhibit, um, or something like that, or a project with musicians kind of collaborating with it on stage. I have one final question for you all. It has to do with kind of the melding of technology and the arts, because that's what we study here at AMTLab, uh, is the intersection of arts and technology. We've seen in the nonprofit art space, how technology plays a role as a disruptor, and I think this kind of scares a lot of arts professionals. So I'm wondering if you have any advice for artists or arts managers who kind of have this fear of technology.

Jim McCann: I'll jump in. I don't presume to give advice here. But I, I will say that it seems like many of the great transformations in what we consider to be say fine art have been spurred on by the development of technology, uh, either in reaction to or adopt or via adoption of said technology. But if you want to get really fundamental, art is artifice, or art is anything that humans make. And technology is what humans use to make things. So there is no antagonism here at root.

Dee Iyer: Um, from more of a musical standpoint. Um, I have played classical piano for as long as I can remember, but um, it was when I started playing in a band and got introduced to what a synth was. Um, That I was like, oh, like electronics do play a massive role in like modern music. Um, and even like back in the earliest days of electronic music you got people, um, making like recordings of um, it sounds they hear in everyday life and turning that into art.

So I would say, technology can be definitely approached through the arts, in terms of, you know, having this artistic background or musical background and then learning specific technology applications for that.

Heather Kelley: I'm gonna jump in here, but it's so hard for me to imagine that there are people in the arts that are afraid of technology. maybe, you know, being at CMU, it's like, who are these people? Um, but I think in the times when I have my misgivings about technology is when I noticed that the, like ethics behind things are not being considered.

And that's really the only case that technology, uh, might seem frightening. And you do see that a bit in the music industry because, you know, there's such a things like, uh, the consolidation right now, there's a lot going on with, with like people being able to go see live shows and what it means for the, you know, the fact that one company basically owns the entire means of accessing, you know, big live performances.

That's just like one example that's in the media right now. I would be concerned about technology's role in the arts in that case, but it isn't because of technology. It's because of, you know, human behavior. So that, that would be my consideration for the ethical, uh, uses that technologies are put to is, is the most important thing to take care of when moving forward with, with the role of technology in, in the arts.

Miles Scharff: I also feel like—I agree with Heather. I, I don't know any people in the arts that are afraid of technology just because of, you know, where we are. But I, I would imagine, um, and the people who, the people who are, maybe feel that like technology promotes disconnection from the actual art because you're, you're getting too caught up in like the technical details or something like that. Yeah, I would just argue that, um, it's just like any other medium, you know? Like once you like, understand it through and through, like you can use it the same way you'd use like any physical tool.

Yuichi Hirose: Um, I was thinking about this question, but, um, I would say that's, I also had a, like, have like a fear, this kinda similar fear. Like I'm doing mechanical engineering basically. And I always think that's, oh, I don't have a lot of CS background, I don't have a lot of EE background and I attended this event, so is it, is it okay or like? I thought about it. Before attending that, but they were all wake up about it and then I was really enjoying this. So I would say that's like everyone probably has sort of this kind of fear. So it's not only about like people from this background really people from any, kind of background, I think to collaborate with some different background.

Natalie Larsen: Yeah, I think all of those are valid points, especially when it's something. Kind of unfamiliar. I mean, we're all kind of naturally afraid of something that's unfamiliar. Um, and yeah, given all the, the ethical issues we've seen in the media with AI. It’s, it's definitely a kind of a scary thing for a lot of people, especially when you don't know too much about it.

Rachel Broughton: I have a follow-up question, Natalie. This is for the whole group, but Heather, you mentioned this space and having the tools you need and the focus of this physical space being playful, like a playground. I'm just curious what you all are excited about playing with next, anything you want to play around with in the future.

Jim McCann: I'll answer with a sort of a boring technical answer, uh, is that playing with analog circuits made me realize there's a lot you can do, even with minute changes in, you know electrical currents or electromagnetic radiation. And that got me thinking about new ways of doing, um, proximity and touch sensing for robotics.

Miles Scharff: I, after doing the fabric tape loop project— The mode of signal reception that I was using, I had, I had learned from a previous experience I had where I was putting contact microphones on the Hot Metal Bridge, and I was able to listen to the radio through that. Um, and this project again, where I was able to like read signals that were going through fabric has really got me thinking about like the physicality of analog signals and, you know, concepts like physical distortion. Like you can't really, like, not like circuitry, distortion, like things that the natural, the natural properties of the physical medium that you're sending a signal through. So I've, I've been experimenting with like different metals and like, you know, old car parts and like trying to read signals through that as well because of this project.

Heather Kelley: Not having known what some of the other jams were, uh, since I've only been to two of them, I might be covering, uh, existing territory. But, when we're working with, you know, fabric based, um, work that having something wearable could be an obvious direction to go in.

Um, and sort of leaning into that maybe with like the kind of perceived coziness of something knitted or, uh, you know, woven in these ways, um, that are possible in the lab. And that there might be, uh, an interesting route to go down. Work that somehow engages with like, I guess you, you know, someone already brought up sense of touch. But maybe also just like sense of warmth or, or coziness. Could there be like a cozy hack?

Dee Iyer: Um, for me, in terms of kind of what this lab got me excited do in the future. Um, I mentioned early electronic music was a lot of music concurrent, which was like recording sounds and turning that into music. I think like that's kind of opened up a lot of potential, because like we see, um, the like huge variety of sounds that can be produced.

Um, With just like a few media. So, uh, I would be excited to kind of take this and experiment with different ways of making electronic music, which, you know, it's not physical. It would be on a computer, but, it's still something I would like to play with in the future.

Yuichi Hirose: Before attending this event, I, thought, I wanted to take more time to learn about analog circuits. I wanted do this. And do lot of research about knitting chain itself.

So if I like know very well about these things. So probably I can with some other ideas of like any other kinda instruments or something. And also, like personally, I like wanna some like old TVs or something is what I came up with.

Rachel Broughton: I love that everyone took that in such different directions. That's awesome. And that everyone gained very different perspectives on how like this can be used as future inspiration.

Natalie Larsen: Thank you for listening to Tech In the Arts. Be on the lookout for new episodes coming to you very soon. If you found this episode informative, educational, or inspirational, be sure to send this to another arts aficionado in your life.

You can let us know what you think by visiting our website, amt-lab.org that's amt-lab.org, or you can send us an email at amtlabcmu@gmail.com. You can follow us on Twitter and Instagram at Tech in the Arts, or on Facebook and LinkedIn at Arts Management and Technology Lab. We'll see you for the next episode.