The hype around non-fungible tokens (NFTs) seems to be reaching a fever pitch. With news of certain digital art pieces selling for tens of millions of dollars and conjecture about what utility these tokens may have outside of the art world, for better or for worse, Web3 has arrived. These technological developments are not just demonstrating a technological evolution, though. They are also creating massive disruption across the visual art industry. The advent of NFTs is spurring a digital renaissance, creating alternatives for artists, galleries, and museums at nearly every step of the process.

Problems in the NFT Realm

An NFT is a non-fungible token or a non-replicable digital item that proves authenticity. They are sold exclusively using cryptocurrency and are considered to be inherently secure because of the decentralized nature of blockchain networks. Any digital file can be minted as an NFT, meaning that videos, music, documents, AI bots, tweets, and more can be uniquely registered on the digital blockchain ledger and put up for sale. So far, visual art is gaining traction as the most common NFT use case. It is important to note, however, that the arrival of NFT technology is not synonymous with new emergent techniques for creating art. Rather it is an instrument for the sale and dissemination of art that can be created through any number of traditional or digital methods. While NFTs could, in theory, offer a more democratic entree into the art world for artists and collectors, they bring issues both novel and familiar to the legacy art world.

Environmental Concerns

Primary amongst the objections to NFTs is the concern about their environmental impact. When Bitcoin and other cryptocurrencies were first created, scarcity was a crucial part of the design. In other words, it is only possible to mine or create a limited number of Bitcoins. As the number of possible new Bitcoins dwindles, it takes more and more electricity and computing power to solve the equations that produce them. Current estimates suggest that “Bitcoin mining uses more power globally per year than some countries, including the Netherlands and Pakistan.” This consumption would be concerning on its own but should elicit particular scrutiny in countries still largely dependent on fossil fuels.

More tangibly, the processes surrounding cryptocurrency mining and transactions begets computer waste. Miners need continuously expanding computer processing power to compete for the diminishing quantity of these coins. As more advanced technologies are developed, miners have a persuasive incentive to toss aside their current devices in favor of new, more powerful ones. This kind of waste alone adds up to over 30,000 tons each year, in addition to other sorts of consumer or industrial tech waste.

Racism

The crypto world also perpetuates the same sort of anonymized bad behavior that is already well known on the internet. Behind the anonymity of a username, one creator or group of creators has created an NFT project titled “Floydies,” a series of NFTs roughly depicting a pixelated George Floyd in a variety of racist scenarios and stereotypes. While OpenSea, one of the primary NFT marketplaces, removed the images from the platform, others are more hospitable to such offensive content. Other NFT projects lean on racist or ableist themes, and such projects are platformed directly to consumers without the kind of guardrails (legitimate, flawed, or otherwise) that traditional arts institutions provide.

Sexism

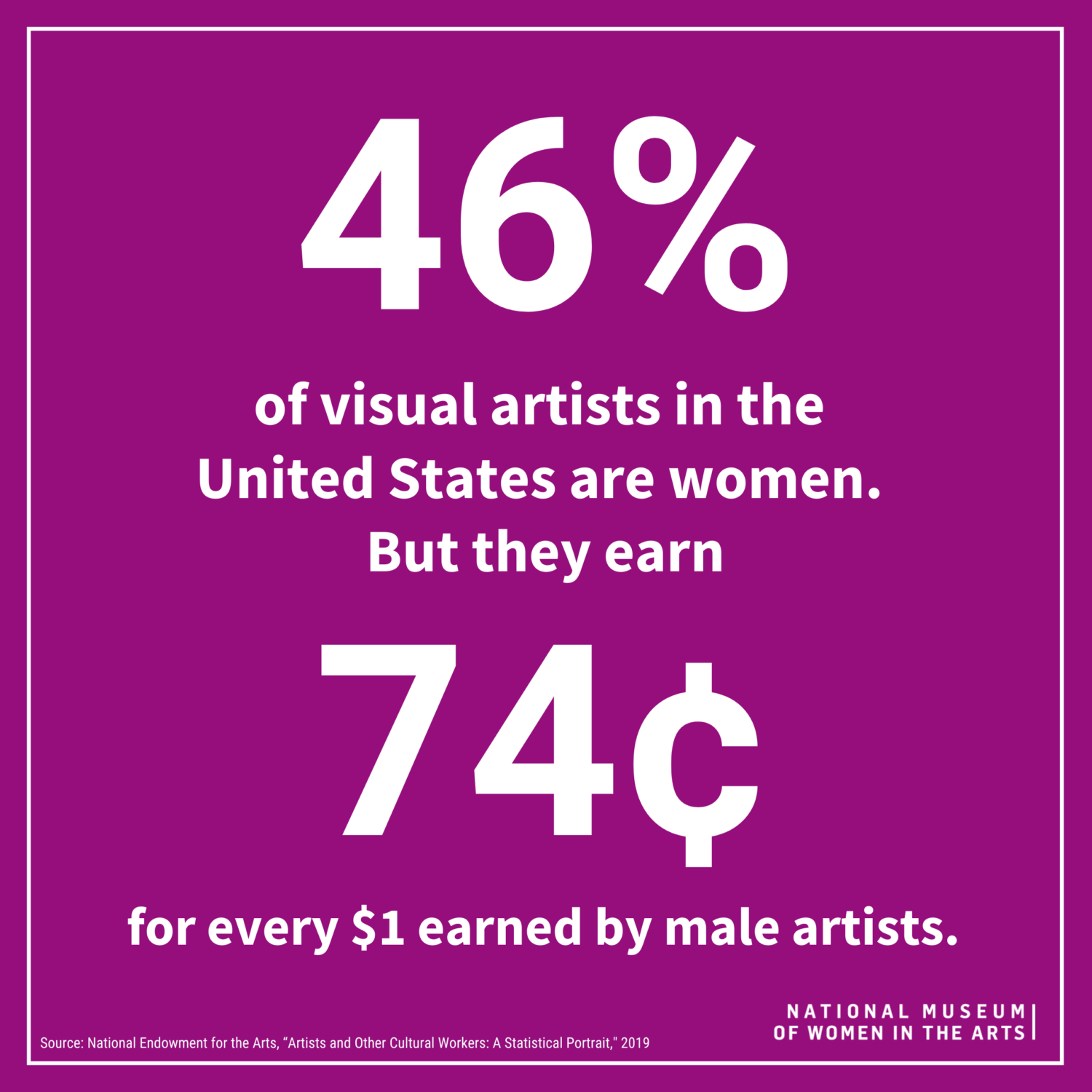

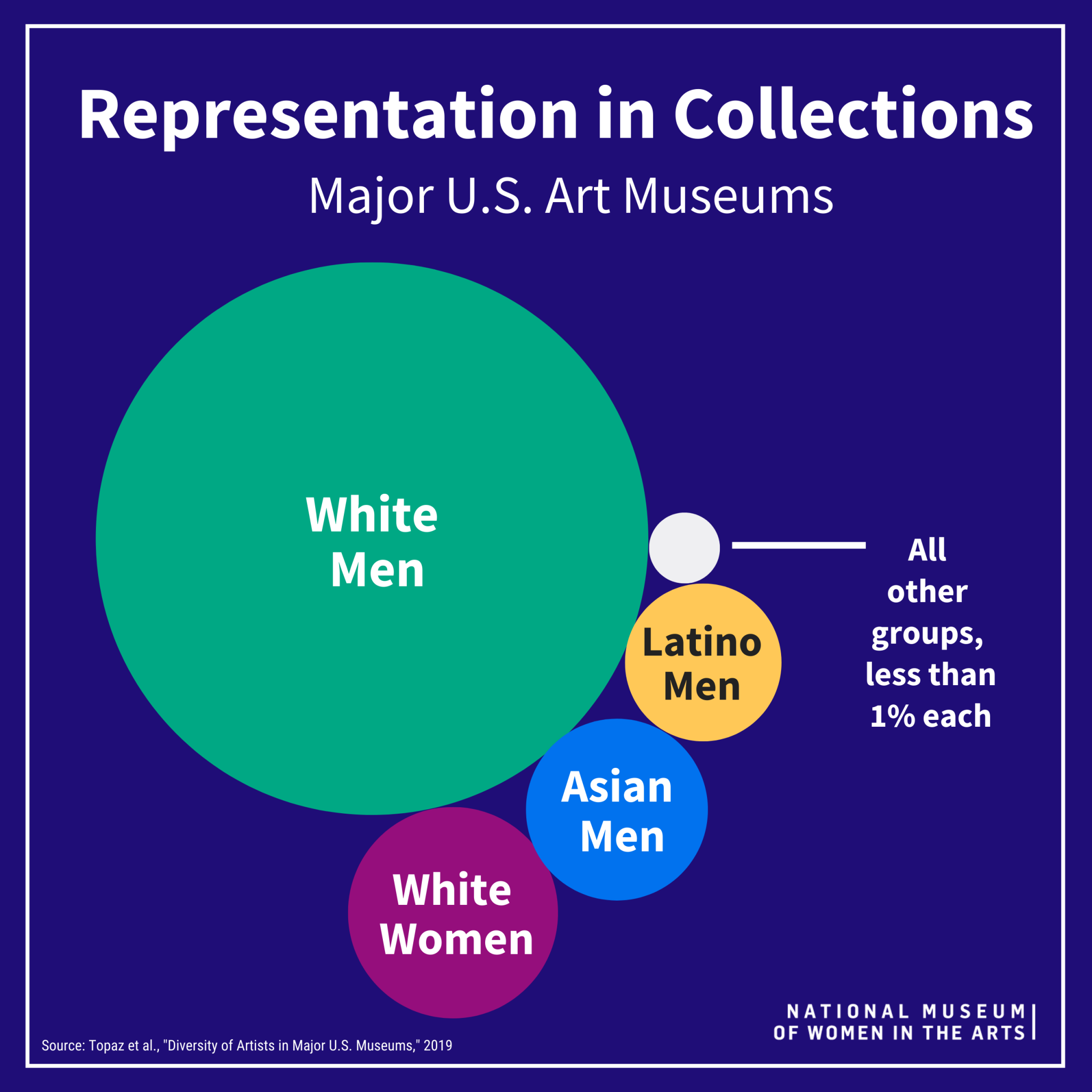

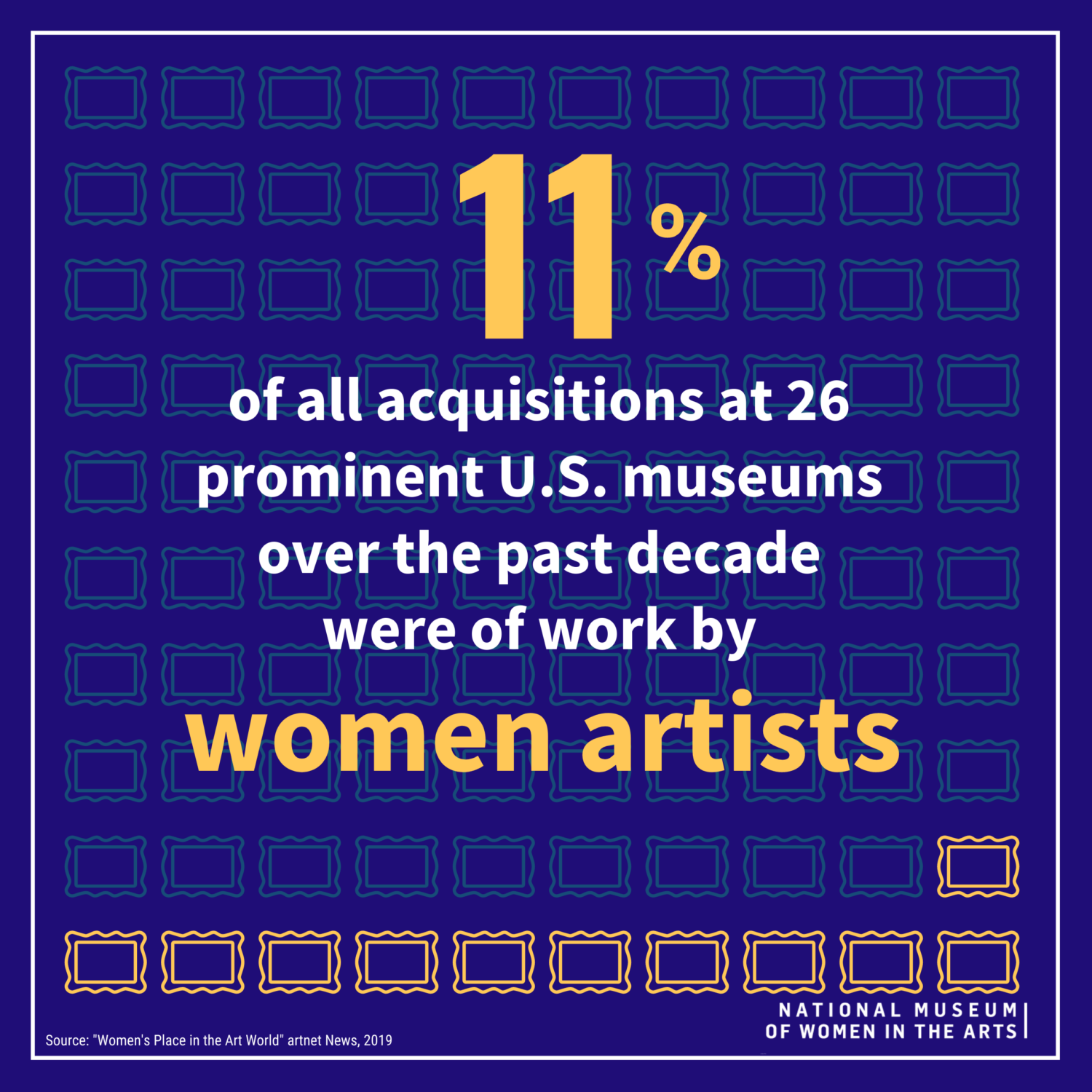

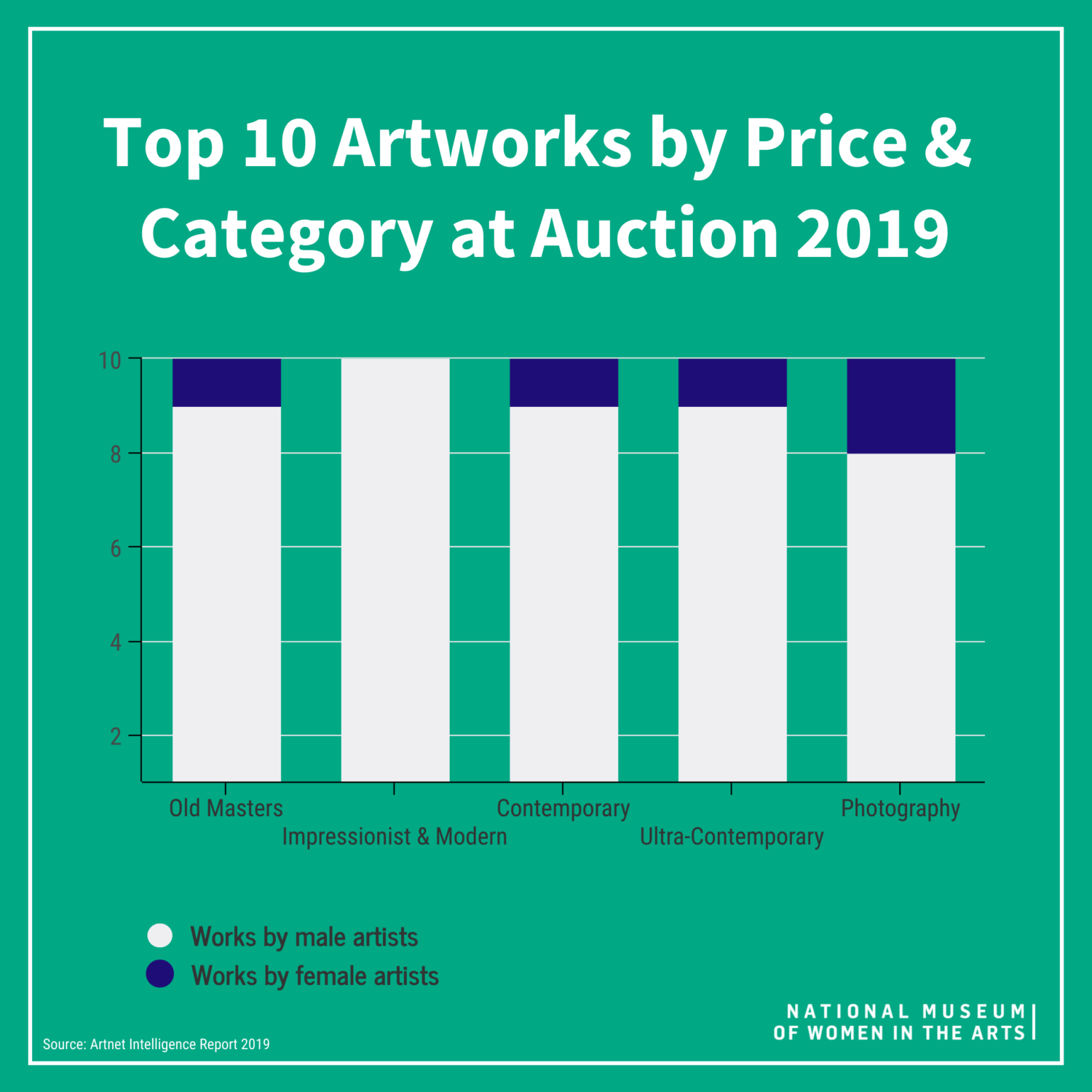

Both the legacy/traditional art world and the NFT space foster extreme gender disparity. The National Museum of Women in the Arts amalgamates data on these discrepancies. These figures are particularly disturbing given that a strong majority of students in university fine art programs (at both the undergraduate and graduate levels) are women. This indicates that the inequities are reinforced by industry, professional, and purchaser prejudices.

Some optimistic women see the NFT space as a solution, full of open opportunities sans glass ceilings, but the full realization of this hope is yet to come to fruition. While the anonymity of these digital transactions could, in theory, support greater gender parity, “female artists accounted for just 5% of all NFT art sales” over a recent 21-month period. The anonymity has also created opportunities for more pernicious deception. In summer 2020, a group of NFT creators posed as “the first ever female-led crypto art collective,” and raised $1.5 million before it was revealed that men were actually behind the enterprise. And the few women invited to speak at in-person NFT panels or conventions find themselves the targets of the same sorts of patriarchal and sexist assumptions and behaviors that continue to govern too many areas of society.

Furthermore, the individuals actively interacting and, therefore, legitimizing this market are largely male. Recent data shows that “one in five online male adults in the U.S. indicated they already own at least one NFT versus just 7% of online female adults.” Given that STEM fields are historically male-dominated, the “crypto bro” reputation of NFT aficionados follows logically.

Money Talks

The make-up of the NFT artist and consumer communities also affects the kinds of images and themes being explored in NFT artwork. As certain NFTs sell for astronomical sums of money, some far eclipsing what revered classic pieces have fetched at auction, some people bristle at “how little [the] aesthetics and modalities [of those NFT pieces] align with traditional fine art values.” Many NFT artists are choosing to reference and riff on a wide spectrum of pop culture icons and imagery, rather than the annals of art history that more formally trained, traditional artists would.

Quantity over quality seems to be a leading philosophy as NFT creators (some of whom are more computer savvy opportunists than artists) race to cash in on the fad. In his video “Why are NFTs so Ugly?,” YouTube creator Solar Sands breaks down how NFT creators create templates for NFT collections and then use algorithms to randomly swap out certain characteristics or accessories in order to generate large numbers of unique images. The result is something obviously computer-generated, that often feels a stone’s throw away from clip art, and jarring in its juxtaposition of characteristics that were collaged together without greater attention to the coherence or integrity of the final piece. In other words, there are a lot of ugly NFTs out there.

Figure 5: Why are NFTs so Ugly? Source: YouTube.

NFTs in Fine Arts Institutions

While one could say that the crypto fad is just a countercultural bubble, established art firms are joining in on the game. Christie’s, the famed auction house, reported its highest sales year in five years after reaping $150 million in NFT sales in 2021. Among these pieces included a digital collage by famous NFT artist Beeple, which sold for $69 million and is the second most expensive piece of digital art sold to date. Christie’s CEO, Guillaume Cerutti, reflected on these sales as an incredible opportunity for the auction house to connect lesser-known artists to new audiences; “75% of buyers in the [NFT] category were new to Christie’s and were an average age of 42 years old.” Conversely, as of 2018, over half of art collectors were Baby Boomers or older.

Museums have found opportunities to participate in and leverage the crypto boom as well. Last year, several digital images created by Andy Warhol in the 1980s were unearthed, translated from an obsolete file format on floppy disks, minted as NFTs, and sold for nearly $3.4 million to benefit the Andy Warhol Foundation. The funds are intended to support the Andy Warhol Museum and other foundation activities. The British Museum has also entered the NFT market by minting pieces originally created by Hokusai and JMW Turner. NFTs, while potentially a creative tool for raising money for these institutions, can, in some cases, blur the lines of ownership and copyrights. Museums, many of which are entangled in a fraught history of art appropriation and theft, ought to tread carefully in the NFT space where distinctions between ownership of the physical versus digital objects and the rights to display either can be less than intuitive.

There is also a new category of museums springing up to satisfy the NFT-curious. The Seattle NFT Museum (SNFTM) just opened in January 2022 as a physical space to “ground the NFT experience, unlocking our imaginations for what is to come.” SNFTM intends not only to offer a platform to display NFTs but also hopes to ignite community around the pieces and the culture.

So, what does this all portend for artists? Are NFTs really the get-rich-quick scheme that so many hope for? The short answer is “it depends who and how lucky you are,” which is not too far off from the qualities that predict success in the traditional art world as well.

““A lot of supertalented digital artists don’t fit the model for the contemporary art world. They don’t go to Art Basel. They’re active on GIF communities. They weren’t monetizing the work as fine art. They might have sold T-shirts on a Linktree.””

In the case of Beeple, whose art set that $69 million record, he stumbled upon exciting opportunities as a digital artist (freelancing on graphics for the SuperBowl and working with Louis Vuitton) but had no clear path to monetizing the art that he created on his own time. NFTs changed everything for him. Beeple, more commonly known by his friends and family as Mike Winkelmann, the congenial Midwesterner, was a complete stranger to the art world with no representation and no formal training. But such signals mean little in the NFT world, and his grotesque, distorted visions of pop culture, politics, and technological perversion have made him many, many fortunes and given him entrée to the formal art world via Christie’s. He now has his sights set on landing a piece in the MoMA (though he also dreams of getting booted from there as well). Beeple is an interesting case study because his success has pushed institutional art toward technological progress (what institution would turn down progress that comes with eight-figure sales?). But other NFT creators may not find the same open-mindedness availed to them, nor may they share the same interest in interacting with these legacy institutions.

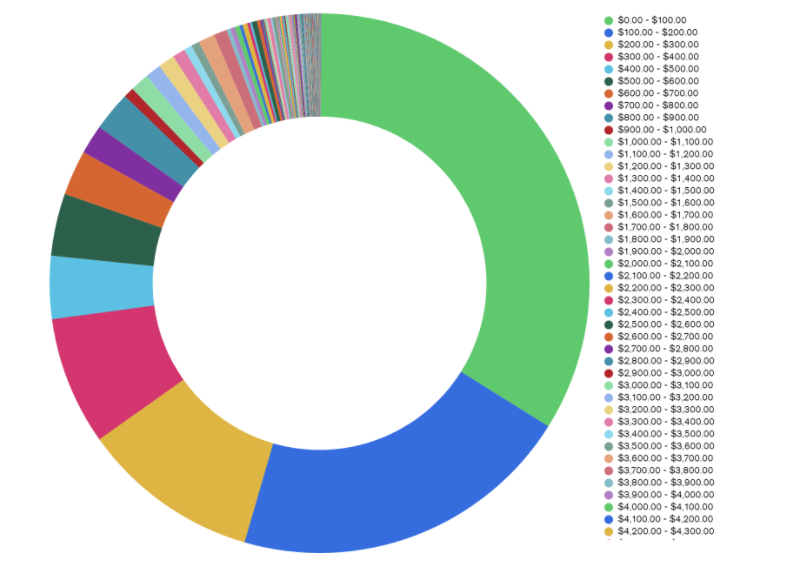

Other creators are extremely unlikely to encounter the kind of financial boons that Beeple has. In April 2021, after Beeple lit up the NFT stage, over 50% of primary NFT sales on OpenSea were for $200 or less. Now consider that OpenSea had nearly 475,000 users in the last 30 days. While this data doesn’t distinguish between buyers and sellers, it’s still clear that becoming a big fish in that pond is pretty improbable, even with the ability to garner additional income through secondary sales.

Figure 6: Graph of NFT Primary Sale Prices on OpenSea from March 14-24, 2021. Source: Artnet.

NFT Takeover?

Some people may think that NFTs sound the death knell for legacy arts organizations and institutions, that NFTs are a line in the sand for artists to similarly get with the times or become irrelevant. For all of the American love of extremism and absolutes, reality is rarely that clear cut. Some galleries will discover that they are no longer viable in this new landscape, though whether that’s to do with technological advancements or their long history of racism, sexism, and abuse, as well as their gatekept wealth remains to be seen. Other galleries and museums will pivot, weaving NFTs into their exhibitions or even switching entirely to in-person exhibitions of digital art. And there are ever more opportunities for gallerists to innovate in online-only spaces, like the ability to design metaverse NFT galleries through Spatial.

Artists are confronted with a similar array of choices. NFT marketplaces are still fairly new, NFT theft is proliferating, and the environmental concerns of the process are surely salient to some. While some artists may look to the crypto world as a way to escape the traps and trappings of the mainstream contemporary art scene, no system is perfect. Relying on these new marketplaces to connect with their audiences and collectors is just a Web3 kind of middleman that takes a cut like all the middlemen before. Some artists, like Amanda Oleander who found early success live-streaming on Periscope, have continued to keep pace with technological advances and are now competing in the NFT space too. Others like Beeple have circumvented the art world to rake in the Ethers. Like nearly all aspects of art and its business, the decisions, ethics, sensibilities, and priorities remain personal, complex, and up for rigorous debate.

+ Resources

Seattle NFT Museum. “About Us.” Accessed February 26, 2022. https://www.seattlenftmuseum.com/about-us.

AlexWGomezz. “NFT Royalties: What Are They and How Do They Work?” Cyber Scrilla (blog). Accessed February 28, 2022. https://cyberscrilla.com/nft-royalties-what-are-they-and-how-do-they-work/.

HYPEBEAST. “‘Andy Warhol: Machine Made’ NFT Collection Raises $3.38M USD at Christie’s Sale,” May 28, 2021. https://hypebeast.com/2021/5/andy-warhol-machine-made-5-nfts-3-38m-christies-sale-info.

Beckett, Lois. “‘Huge Mess of Theft and Fraud:’ Artists Sound Alarm as NFT Crime Proliferates.” The Guardian, January 29, 2022, sec. Technology. https://www.theguardian.com/global/2022/jan/29/huge-mess-of-theft-artists-sound-alarm-theft-nfts-proliferates.

BBC News. “Bitcoin Mining Producing Tonnes of Waste,” September 20, 2021, sec. Technology. https://www.bbc.com/news/technology-58572385.

Bogna, John. “What Is the Environmental Impact of Cryptocurrency?” PCMAG. Accessed February 25, 2022. https://www.pcmag.com/how-to/what-is-the-environmental-impact-of-cryptocurrency.

Calma, Justine. “The Climate Controversy Swirling around NFTs.” The Verge, March 15, 2021. https://www.theverge.com/2021/3/15/22328203/nft-cryptoart-ethereum-blockchain-climate-change.

Cancel Galleries. “How We Can Hold Art Galleries Accountable.” Hyperallergic (blog), January 15, 2021. http://hyperallergic.com/614715/how-we-can-hold-art-galleries-accountable/.

Cascone, Sarah. “Depressing New Report Finds That Women Artists Accounted for Just 16 Percent of NFT Sales Over the Past 21 Months.” Artnet News (blog), November 5, 2021. https://news.artnet.com/market/nft-sales-just-16-percent-women-2030490.

Chen, Jiayin. “‘Idols Are Dead’: TRON Founder Justin Sun on the Opportunities That Crypto Art Presents for His Rising Generation.” Artnet News, January 24, 2022. https://news.artnet.com/market/justin-sun-interview-apenft-2062888.

Clark, Mitchell. “People Are Spending Millions on NFTs. What? Why?” The Verge, March 3, 2021. https://www.theverge.com/22310188/nft-explainer-what-is-blockchain-crypto-art-faq.

Cryptured Team. “According to a Study, Male Creators Account for at Least 77 Percent of NFT Art Sales.” Cryptured.Com (blog), November 18, 2021. https://www.cryptured.com/male-creators-account-for-at-least-77-percent-of-nft-art-sales/.

Dave, Anushree. “NFT Art Market Boom Is Overwhelmingly Benefiting Male Creators.” Bloomberg.Com, November 9, 2021. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2021-11-09/nft-crypto-art-market-boom-biggest-sales-going-to-male-artists-women-lag.

DuChene, Courtney. “NFTs Are Disrupting Fine Arts: Here’s What Risk Professionals Should Know.” Risk & Insurance (blog), February 22, 2022. https://riskandinsurance.com/nfts-are-disrupting-fine-arts-heres-what-risk-professionals-should-know/.

Dumont, Rowynn, and Page Carpenter. “NFT Art and What It Means for Artists, Buyers and the Future of the Art Market.” Agora Gallery – Advice Blog (blog), July 23, 2021. https://www.agora-gallery.com/advice/blog/2021/07/23/nft-art-and-what-it-means-for-artists-buyers-and-the-future-of-the-art-market/.

Fenton, Cheryl. “Enter the Digital Art World at Boston’s First NFT Show.” Boston.Com. Accessed February 28, 2022. https://www.boston.com/things-to-do/untagged/enter-the-digital-art-world-at-bostons-first-nft-show/.

“Fossil Fuels — The National Academies.” Accessed February 28, 2022. http://needtoknow.nas.edu/energy/energy-sources/fossil-fuels/.

Garcia, Evan. “Chicago’s First Physical NFT Gallery Drops Digital Art.” WTTW News, November 16, 2021. https://news.wttw.com/2021/11/16/chicago-s-first-physical-nft-gallery-drops-digital-art.

NMWA. “Get the Facts About Women in the Arts.” Accessed February 26, 2022. https://nmwa.org/support/advocacy/get-facts/.

Grosvenor, Bendor. “The British Museum Demeans Itself by Selling Its Works as NFTs—and Will Probably Live to Regret It.” The Art Newspaper – International Art News and Events, February 9, 2022. https://www.theartnewspaper.com/2022/02/09/the-british-museum-demeans-itself-by-selling-its-works-as-nftsand-will-probably-live-to-regret-it.

Hale, Jacob. “Top 10 Most Expensive NFTs Ever Sold.” Dexerto (blog), February 17, 2022. https://www.dexerto.com/tech/top-10-most-expensive-nfts-ever-sold-1670505/.

Kim, Eddie. “George Floyd NFTs Are Just the Tip of a Racist Crypto Iceberg.” MEL Magazine (blog), February 15, 2022. https://melmagazine.com/en-us/story/floydies-racist-nfts.

Kinsella, Eileen. “Think Everyone Is Getting Rich Off NFTs? Most Sales Are Actually $200 or Less, According to One Report.” Artnet News, April 29, 2021. https://news.artnet.com/market/think-artists-are-getting-rich-off-nfts-think-again-1962752.

———. “Women and Millennials Are the Fastest-Growing Forces in Art Collecting, a New Study Finds.” Artnet News, June 26, 2018. https://news.artnet.com/market/art-wealth-survey-women-millennials-1309265.

Locke, Taylor. “These Millennial Creators Are Making 6 Figures Selling NFTs: ‘It Changed the Trajectory of My Career and My Life.’” CNBC, May 12, 2021, sec. Make It: Next Gen Investing. https://www.cnbc.com/2021/05/12/meet-the-millennial-creators-making-six-figures-selling-nfts.html.

Marple, Mieke. “What’s Really at Stake in the Debate over Whether NFTs Are Art.” Artsy, January 24, 2022. https://www.artsy.net/article/artsy-editorial-stake-debate-nfts-art.

Maruma, Misha. “An Artist-Centered NFT Platform?” Hyperallergic (blog), February 21, 2022. http://hyperallergic.com/712094/an-artist-centered-nft-platform/.

McLaughlin, Rosanna. “‘I Went from Having to Borrow Money to Making $4m in a Day’: How NFTs Are Shaking up the Art World.” The Guardian, November 6, 2021, sec. Art and design. https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2021/nov/06/how-nfts-non-fungible-tokens-are-shaking-up-the-art-world.

Mozée, Carla. “Christie’s Sold $150 Million of NFTs in 2021, with the Auction House on Track for $7.1 Billion in Sales for the Year.” Markets Insider. Accessed February 26, 2022. https://markets.businessinsider.com/news/currencies/christies-nft-sales-total-beeple-auction-crypto-cryptopunks-2021-12.

“NFT Gallery: Create Your Own Metaverse Art Gallery.” Accessed February 28, 2022. https://spatial.io/create-your-gallery.

Statista. “NFT: User Count 2017-2021.” Accessed February 28, 2022. https://www.statista.com/statistics/1266322/nft-user-number/.

Financesonline.com. “Number of Blockchain Wallet Users 2022/2023: Breakdowns, Timelines, and Predictions,” March 23, 2020. https://financesonline.com/number-of-blockchain-wallet-users/.

OpenSea. “Amanda Oleander – Collection.” OpenSea. Accessed February 28, 2022. https://opensea.io/collection/amandaoleander-collection.

DappRadar. “OpenSea.” Accessed February 28, 2022. https://dappradar.com/ethereum/marketplaces/opensea.

“OpenSea, the Largest NFT Marketplace.” Accessed February 28, 2022. https://opensea.io/.

Queue-it. “39 NFT Ideas & Examples: The Wild, the Weird & the Wonderful.” Queue-it. Accessed February 25, 2022. https://queue-it.com/blog/nft-ideas-for-inspiration/.

Rapkin, Mickey. “‘Beeple Mania’: How Mike Winkelmann Makes Millions Selling Pixels.” Esquire, February 17, 2021. https://www.esquire.com/entertainment/a35500985/who-is-beeple-mike-winkelmann-nft-interview/.

Scott, Andrea K. “The Year the Art Scene Rebounded, Expanded, and Surrendered to N.F.T.s.” The New Yorker, December 23, 2021. https://www.newyorker.com/culture/2021-in-review/the-year-the-art-scene-rebounded-expanded-and-surrendered-to-nfts.

Scott, Caitlin. “Amanda Oleander Is Periscope’s Breakout Star.” Cosmopolitan, June 8, 2015. https://www.cosmopolitan.com/entertainment/a39971/amanda-oleander-internets-most-fascinating/.

Shoenthal, Amy. “The Women Of The Metaverse.” Forbes, February 8, 2022. https://www.forbes.com/sites/amyschoenberger/2022/02/08/the-women-of-the-metaverse/.

Small, Zachary. “After Pak and Beeple, What’s Next for NFT Collectors? Art Made With a Paintbrush.” The New York Times, February 12, 2022, sec. Arts. https://www.nytimes.com/2022/02/12/arts/design/nft-collectors-artwork.html.

Smee, Sebastian. “Will NFTs Transform the Art World? Are They Even Art?” The Washington Post (Online). December 18, 2021, sec. Entertainment. https://www.proquest.com/docview/2611204276/citation/8A61289744E64D0BPQ/1.

Solar Sands. Why Are NFTs so Ugly?, 2022. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wDtt24RxdLk.

Truby, Jon. “Decarbonizing Bitcoin: Law and Policy Choices for Reducing the Energy Consumption of Blockchain Technologies and Digital Currencies.” Energy Research & Social Science 44 (July 1, 2018). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.erss.2018.06.009.

Wright, Grace. “Physical NFTs: Can Physical Art Be an NFT?” Urth Magazine (blog), January 18, 2022. https://urth.co/magazine/physical-nft/.